By Harry Kloman

Sept. 25, 2009

Of all the questions from University of Pittsburgh students that Russian President Dimitry Anatolyevich Medvedev answered Thursday afternoon in his hour of improvised political theater - questions about relations with Georgia and the Ukraine, about diamond mining in Siberia, about the most important thing in life ("love") - the thing that rattled him (if anything did) were two questions about whether he'll run for re-election in 2012.

Not that I could tell exactly. Of course, everyone knows that Medvedev became president two years ago because the Russian constitution forbade President Vladimir Putin from succeeding himself a second time. And everyone knows that Putin became Medvedev's prime minister because Putin said he would become Medvedev's prime minister. But now Putin can run again in 2012, so Medvedev naturally has to watch what he says. If (when) Putin returns to the presidency, Medvedev would certainly expect a valuable consolation prize.

So yes, the current president said, I would enjoy being president again, if the people like and trust me. But maybe, he said, someone else might run, and being prime minister would be an honor for anyone.

Surely everyone in the audience who knew anything about Russian politics knew he was caught between an old-style Soviet rock and a hard place. But was he uncomfortable talking about it?

Well, perhaps a little, the Russian journalist sitting next to me confided when I asked her (twice).

At the gathering, I had the good fortune to poach a seat among three rows of Russian journalists traveling with President Medvedev. I listened to his talk through my translation headset, but now and then, when he wasn't saying something even remotely funny, the Russians surrounding me chuckled and smiled. During one of Medvedev's answers, about making the Russian judiciary "absolutely independent and impeccable," a few of the Russian journalists shook their heads from side to side in that slow scolding manner that apparently translates without the need for an interpreter. Clearly, there was a subtext.

Still, my journalist friend from Moscow said she was grateful that this president answers every question. Past Soviet - er, Russian - presidents apparently did not.

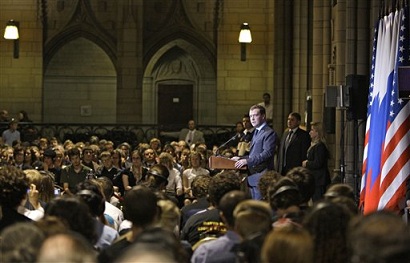

Medvedev's talk in the commons room of Pitt's Cathedral of Learning began an hour past its scheduled 4 p.m. start. With Pittsburgh a logjam of roadblocks and protests because of the G-20 summit, and with the city never easy to get around anyway, certainly nobody expected it to begin on time.

But after some congenial opening remarks by Chancellor Mark Nordenberg, during which we learned that Medvedev had sat in on a Russian lit class taught, in Russian, in the Russian Nationality Room, Medvedev took a few minutes to explain that his late arrival wasn't his fault and that there was "noting I could do about that." This felt very Russian, for being at fault there can still get you a one way ticket to Palookagrad.

During his talk, Medvedev was often wryly witty, but he almost never smiled. I asked my counterpart about it, and she said, after some prodding, that "it's not our custom." She also said that Obama smiles all the time (which is why I asked), and that after too many smiles, he begins to feel a bit fake (which, again, is why I asked).

Medvedev said he welcomed frank talk about our difference, which "stimulates our humanity throughout the millennia," and after a question about containing Iran's nuclear proliferation, he began, "I have this feeling I'm still in the meeting with Barack Obama." The translators did their best to capture the nuances of his colloquial speech - what's the Russian word for "comfy"? - and Medvedev said he couldn't talk about what he'll discuss at the summit because he wouldn't want the other G-20 leaders to feel jealous that the Pitt audience heard it first (here, he smiled just a little).

The hour's most challenging question came from a woman who wanted to know if the government would share the riches of the country's diamond region with that region. To answer, Medvedev gave the floor to his finance minister, Alexei Kudrin, who rose and immediately told people that in addition to his government post, he's chairman of the board of one of the country's largest diamond companies. In America, that would get you fired, and after that, a job as a lobbyist. But in Russian, Medvedev explained when his minister sat down, it's simply how they do it. (Who better to look after such an important asset, this system implies, than the finance minister?)

A former lawyer and college professor, Medvedev seemed a bit stiff in his brief opening remarks but very relaxed during his long Q&A, moving his attention around the room to let students on all sides ask questions, and pointing to each questioner, in good diplomatic form, with four outstretched fingers and his thumb tucked into his palm.

The interlocutors were well informed, some asking questions in Russian, and a member of Pitt's Russian Club called him "Dmitry Anatolyevich," using the traditional Russian patronymic form of addressing someone. (It means "Dimitry, son of Anatoly.") The audience stood in applause when he finished, and then his handlers hustled him away for dinner with the Gang of 20 at Phipps Conservatory, where a row of riot police blocked access from the direction of Pitt's campus, sending up a mist of irritant to push back the protestors approaching from the bridge beside the Cloud Factory.