On the Ethics of Imaginary Research

John D.

Norton*

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

Center for Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

www.pitt.edu/~jdnorton

The purpose of this note is to

draw attention to hitherto overlooked ethical problems raised by the now

widespread techniques of imaginary research. Three principles are proposed as

ethical guides for future research practice.

1

Introduction

Real experimental practice has long been controlled by multiple regulations,

designed to prevent a wide range of improper experimental

procedures.1 They ensure the dignified treatment of human subjects

and the humane treatment of experimental animals. Researchers conducting real

experiments routinely submit their protocols for the approval of IRB's,

Internal Review Boards, and research establishments maintain appropriate

registration.

Imaginary experimentation and research has so far been exempt from similar

regulatory attention. This lapse results from the dismissal as merely imaginary

of the harms that may arise from imaginary experimentation. In the broader

philosophy of science and philosophy of mathematics literature, realism remains

a hotly contested viewpoint. Yet the realist prejudice that strictly partitions

everything into real and imaginary is all that sustains this dismissal of

imaginary harms.

2

It has long been apparent that a more complex analysis of the real and

imaginary is needed. What has prevented a full recognition of the scope of the

imaginary harm wrought by imaginary experimentation is a lack of adequate

documentation. One can scarcely doubt the irresponsibility of Galileo's Sagredo

when he cast canon balls "weighing one or two hundred pounds or more" from the

heights.2

Since no reports are given, we can only imagine the peril this experiment

brought to innocent passers-by. Indeed we can now see the utter moral vacuity

of Salviati in his excoriation of Aristotle for not imagining just such an

experiment.

One may argue that the vague description of the location of Sagredo's

experiment means, at best, that no one person specifically was endangered, or,

at worst, that the dangers were widespread and thus diluted. Unfortunately

later implementations of Sagredo's experiment have been more specific in their

placement and thereby localized the imaginary harms more narrowly.

3

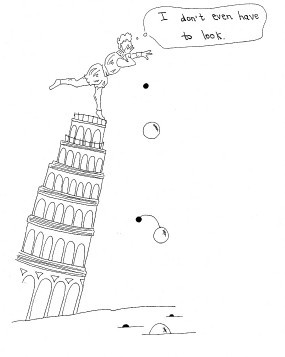

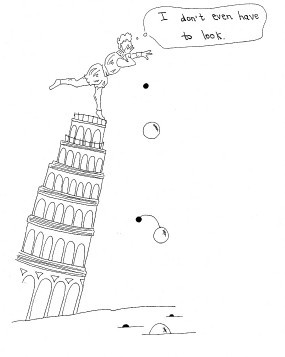

The distinctive leaning tower of the figure and the period dress locate the

experiment in sixteenth century Pisa, just as it illustrates the willful

negligence of the experimenter.

One would like to think that the tradition of thought experimentation

initiated by Galileo evolved towards more benign experiments in the hands of

later, more enlightened practitioners. Unfortunately, with greater theoretical

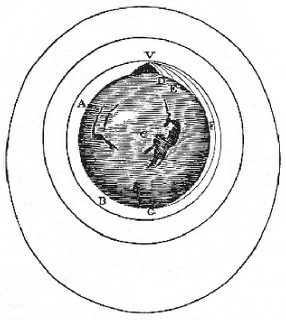

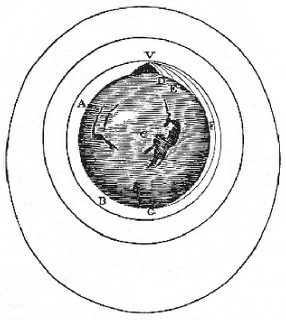

power comes the ability to wreak greater harm. We need only look to Newton's

famous imaginary experiment of a stone projected from a mountain into

dangerously low earth orbits.3

The figure is too coarse for us to see the dangers to inhabitants of many

continents. We can only imagine them.

4

This reckless experimental practice must submit to the discipline of

principles and regulation. In the following, I will articulate three ethical

principles to which, I urge, all practitioners of imaginary research must be

held.

First Principle

Non-existence does not deprive a living being of rights.

We have long accorded rights to non-existents. A familiar example arises in

the case of someone discharging a firearm in a crowd. Even if the discharge

harms no real person, the perpetrator is still guilty of gross negligence and

is subject to prosecution and punishment. We justify this treatment by

imagining what could have happened. What if someone were in the line of fire?

The outcome could have been deadly.

That is, we are quite willing to exact severe legal penalties in defense of

the rights of an imaginary person whose harms are only imagined.

A related matter that will not be pursued here in the detail it deserves is

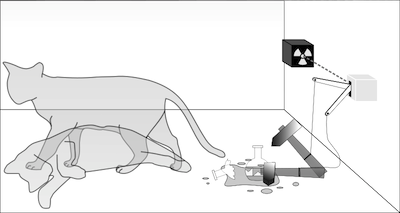

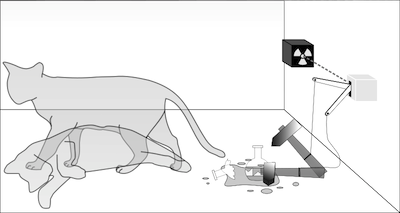

the mistreatment of animals. It is, sadly, routine in the practice of imaginary

research. Only the most egregious of cases have received popular attention. Who

has not been horrified at the sadistic torture by Erwin Schoedinger of his cat?

Yet it is tolerated merely because the poor beast has the additional misfortune

of non-existence.

5

Second Principle

All imaginary experimentation must be subject to cost-benefit

analysis.

This principle is no different from the demand placed on real

experimentation. Medical research that proves lethal to an experimental subject

may yield results that save future lives. Yet the cost of the lives assuredly

lost is universally judged greater than the benefit.

In the case of thought experimentation, one must always ask if the

experimental goals might be achieved better by a real experiment. One might

think that an imaginary experiment is always to be preferred to a real one in a

cost benefit analysis. For the real harms brought by a real experiment are most

likely vastly worse than the imaginary harms of an imaginary experiment.

While that relative assessment of the magnitude of possible harms of real

and imagined experiments is likely correct, it does not take into account the

frequency with which the experiments are conducted. Real experiments are rarely

conducted more than once or twice; they are too hard and too expensive. An

experiment in thought, however, once it is created, can be replicated at will.

If it is well-crafted, just this is likely to happen.

Even if the harm wrought with each replication of the imaginary experiment

is minuscule, the accumulated harm of very many repetitions can readily exceed

the harm of a single execution of a real experiment, especially if the latter

is well-controlled.

If it is determined that a thought experiment is unavoidable, a corollary is

that the least harmful design should be sought, compatible with the successful

functioning of the experiment. Schroedinger did not need to torture a cat to

achieve his result in quantum theory. A mouse or even a cockroach would have

sufficed. But an amoeba would not.

6

Third Principle

Thought experimentation must proceed under informed consent.

The author of a thought experiment carries a special burden not placed on

creators of real experiments. For all readers become the author's research

assistants, actively participating in the execution of the experiment.

Imaginary scenarios can be created in text quite rapidly and so fast that the

reader can become an unwitting accomplice in the creation of imaginary harms.

What if you are a brutal dictator of a small nation who oversees the mild

reprimand of a few innocent citizens. The harm has been imagined before the

reader has a chance to consent to participation in its creation.

In this case, the damage was small. It was merely misplaced reprimands. But

what if it had been a genocide?

More difficult issues are raised by the choice of language. What if a

thought experiment involving great harm is written in a language a reader does

not know. Do we discount the harm merely because the reader did not understand

the language read? We are loath to issue complete exculpation for speech acts

on these grounds. A person inciting a mob to violence by calling "kill him" is

not excused if we learn that the person calling does not understand English.

Should it be any different with imaginary experiments? What if the experiment

is read aloud?

7

Conclusion

One may doubt whether these three principles will survive longer term

philosophical scrutiny. That remains to be seen. However one should not allow

those doubts concerning the future to prevent action in the present. As long as

we are unsure of the severity and extent of the harms created by imaginary

research, we should act prudently to limit the possible harms. We cannot assume

that realists' hesitations concerning imaginary harms will prevail over the

well-reasoned fears of the anti-realists. We cannot play "wait and see," while

risking the multiplication of harms that may be irreparable.

How does one heal the concussion of an imaginary passer-by or the poisoning

of a fictitious cat? Is the cat I bring back to life in my imaginary medical

experiment the same one that died in your experiment? Or have my efforts to

revive your casualty merely duplicated the harm?

As long as these doubts remain, I call upon universities and other research

centers to implement Internal Review Boards for imaginary experimentation and

that these IRBs be commissioned to hold their researchers to the principles

enunciated here.

8