| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

So far all our discussions in special relativity have involved the motion of bodies in space over time. If you haven't already noticed, these motions can become rather complicated to visualize. Take the simple case of a rod with a light signal bouncing back and forth between its ends.

Now describe the same system from a different frame of reference.

Recall how tough it is to keep track of events at the ends of the rod. In one case, the events of the reflections of the signal are evenly spaced in time. In the other, they are staggered. The difference matters a great deal, since it is a manifestation of the key effect of the relativity of simultaneity. But you cannot just look at the figure and see the effect. You have to play out a little movie in your head.

|

In 1907 the mathematician Hermann Minkowski explored a way of visualizing these processes that proved to be especially well suited to disentangling relativistic effects. This was their representation in spacetime. Quite puzzling relativistic effects could be comprehended with ease within the spacetime representation and work in the theory of relativity started to be transformed into work on the geometry of spacetime. |

| We build a spacetime

by taking instantaneous snapshots of space at successive instants of

time and stacking them up. It is

easiest to imagine this if we start with a two dimensional space.

The snapshots taken at different times are then stacked up to give

us a three dimensional spacetime. In this spacetime, a small body at

rest will be represented by a vertical line. To see why it is

vertical, recall that it has to intersect each instantaneous space

at the same spot. A vertical line will do this. If it is moving, it

will intersect each instantaneous space at a different spot; a

moving body is presented by a line inclined to the vertical. A standard convention (that I will usually use) is to represent trajectories of light signals by lines at 45o to the vertical. In the figure, a moving rod is represented by the trajectories in spacetime of its ends. The zig-zag line is a light signal bouncing back and forth between these two ends. |

| A point that moves inertially, that is, a point that moves uniformly in a straight line in space is represented by a straight line in a spacetime. For such a motion covers the same distance in the same time. |

Here's another example. Take snapshots of the earth orbiting the sun in the three dimensional space around the sun in the course of a year, which will look like:

| Now we stack them up into the third dimension. |

| When we clean things

up a little, we have a spacetime. |

So far we have described how a two dimensional space is combined with the one extra dimension of time to generate a three dimensional spacetime, such as shown above in the figures. Our space is three dimensional. So when we add the extra dimension of time we generate a four dimensional spacetime.

| There is no easy way to draw a picture of a four dimensional spacetime. Visualizing it can be very hard. But that does not make it mysterious. It is just another sort of space that happens to transcend simple visualization. In physics, four dimensions are actually quite modest. In statistical mechanics, we routinely deal with phase spaces of 6 x number of molecules in a gas sample. For even small samples of gas, that can come to 1025--a space with 10000000000000000000000000 dimensions. So we should not be too awed by a mathematical space with only four dimensions! | If learning how to work with a four

dimensional space interests you, see this chapter "What

is a four dimensional space like?" |

That the speed of light is a constant is one of the most important facts about space and time in special relativity. That fact gets expressed geometrically in spacetime geometry through the existence of light cones, or, as it is sometimes said, the "light cone structure" of spacetime.

To see that structure, we imagine an event at which there is an explosion. Light will propagate out from it in an expanding spherical shell. In a two dimensional space, it will look like an expanding circle, as shown below.

| To see that structure, we imagine an event at which there is an explosion. Light will propagate out from it in an expanding spherical shell. In a two dimensional space, it will look like an expanding circle. |

|

An animations makes the motion more visible. |

Now stack up these spatial snapshots to make a spacetime. The spacetime diagram that corresponds to it looks like a cone. As we proceed up the cone, we look in each instantaneous space to see how far the light has propagated. Each intersection of the cone with the space will be a circle.

In the figure, the expanding circle of light is represented by the top half of the cone. It is customary to draw in the bottom half of the cone, although it is not part of the expansion of the light. In fact it represents the opposite. It depicts a circle of light collapsing in towards the original event at the apex of the cone. Here is that collapse, presented also as an animation.

A final animation now shows the association between the different stages of the collapsing and expanding light shell and the cross-sections of the light cone.

To have a light cone, we do not need light to be present. The cones map out the trajectories light would take if light were to be present. Since it is just the possibilities that are mapped out, not necessarily the trajectories of actual light. Spacetime still has a light cone structure in the dark!

To describe the light cone just now, we picked an event in spactime and imagined all the possible trajectories that light could take in propagating through that event. We could have picked any event in the spacetime. We would have found lightcones at every one of them. That means that spacetime is completely filled with light cones. There is one at every event.

There is much potential for confusion in talking about

spacetimes. As a result a fairly precise vocabulary has been built up and

it is important to to use it correctly. Pay

attention to the following terms:

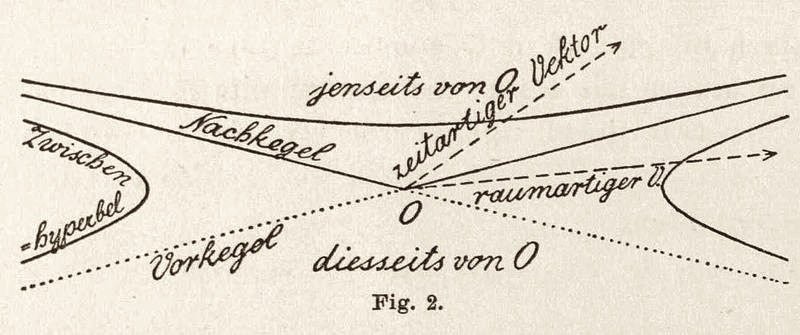

| Spacetime

When we add the extra dimension of time to a space, we produce a

spacetime. Minkowski spacetime There is nothing special about a spacetime. They can arise in classical physics. So if we mean a spacetime that also behaves the way special relativity demands, then we have a Minkowski spacetime. (Note for later: when we look at general relativity, we will meet spacetimes that are relativistic but not Minkowski spacetimes.) Event These are the individual points of a spacetime. They represent points in space at a particular time. Timelike Worldline This is the trajectory of a point moving less than the speed of light. These curves are contained within the light cone. They represent the trajectories of ordinary particles, like electron, protons and neutrons, but not photons. Lightlike curve This is the trajectory of a point moving at the speed of light--a light signal or a photon. They lie on the surface of the light cone. Spacelike curve This is a curve that lies outside the light cone. If an object is to make this curve its trajectory, it would need to travel faster than light. Spacelike hypersurfaces These are the instantaneous spatial snapshots of spacetime. They are three dimensional in the case of a four dimensional spacetime. Past and future light cones All the lightlike curves through an event form the light cone at that event. The part of the cone to the future of that event is the future light cone. The part to the past is the past light cone. Light cone structure Since the speed of light is generally taken to be the fastest that causes can propagate their effects, once we know how the light cones are distributed in space we can say a great deal about what is possible and impossible causally in the spacetime. So this distribution is of great interest to us. It is called the light cone structure of the space. Timelike geodesic These are curves that are the possible trajectories in spacetime of inertially moving points. They are straight lines that lie within the lightcone. This technical term "geodesic" will be explained later. |

| For a curve to be timelike, it must lie within the lightcones everywhere along its length. |

| For a curve to be lightlike, it must lie on the lightcones everywhere along its length. |

For a curve to be spacelike, it must lie outside the lightcones everywhere along its length.

Knowing the light cone structure of a spactime tells us what connects with what. Its importance is comarable to what is represented on ordinary maps of countries. Here is a map of ancient Greece:

Greece at the beginning of the Peloponnesian

war. p. 17 in W. S. Shepherd, Historical Atlas, New York: Henry Holt

& Co., 1911.

We read from the map that, if we are in Greece, we can travel North and eventually arrive in Thrace. However we cannot get to Crete; or at least we cannot get to Crete by land. We would need to cross a sea.

| The light cone structure catalogs

analogous "what connects with what" information for a spacetime. It

reveals its most basic geography. To see how this works, pick any event "O" in the spacetime. The future light cone at O contains all the events in the spacetime that can be reached from O by future directed timelike or lightlike curves. If we make the usual assumption that all causal processes propagate at or less than the speed of light, we conclude that these are all the events that we can causally affect from O. More simply, if you are at O, the events in the forward light cone are just those events that you can reach with a physical signal, such as an ordinary particle or a light flash that you may emit. |

|

| For that same event O, the past

light cone contains all the events in spacetime from which

one can reach event O by future directed timelike or lightlike

curves. Assuming again that all causal processes propagate at less than or equal to the speed of light, we conclude that this past light cone contains all the events that can causally affect event O. More simply, if you are at any event in the past light cone of O, you can always send to O a physical signal consisting of an ordinary particle or a light flash. |

|

| The remaining region of the spacetime

is outside both past and future light cones. It is a new sort of

region that does not appear in pre-relativistic spacetimes. It is an

"elsewhere" region. It collects all events that cannot be connected to event O by timelike or lightlike curves. Its events can only be connected to O by spacelike curves. That is, its events are "spacelike separated" from O. If we assume that no causal processes propagate faster than light, these events are causally disconnected from O. If we are at O we cannot causally affect or be causally affected by an occurrence at an event in this "elsewhere" region. Correspondingly, we cannot exchange signals between the event at O and any spacelike separated event in this region. There is no corresponding region in a pre-relativistic spacetime. In Newtonian theory, it is assumed that there are propagations that are arbitrarily fast and even instantaneous. An example of an instantaneus propagation is changes in the Newtonian gravitational field. If the sun were to disappear, we would know instantly on earth, according to Newtonian theory, for the sun would no longer exert a gravitational pull on us. |

A Minkowski spacetime has a geometry in a sense that is analogous to the geometry of an ordinary Euclidean space. They are both "metrical" geometries. That means that they are geometries that deal with distances.

| Euclidean geometry is the familiar case. It consists of two things: a set of points, and an exhaustive inventory of the distances between all pairs of points. In principle, we would need to list all the distances between each point and every other point. In practice, the task is a lot easier. If we merely specify the distances between each point and its neighboring points, we can then determine all the remaining distances. I will leave the discussion here since we are enterring technical areas that we need not deal with now. |

| One of the simplest constructions in a Euclidean geometry is a circle. A circle is just the locus of all points at the same distance from some designated central point. The figure shows two circles, of radius 1 and of radius 2. They are the loci of all points that are unit distant and 2 units distant from the central point. |

Minkowski spacetime also has a metrical geometry. Instead of Euclidean points it is based on spacetime events. The geometry specifies the spacetime distance from each event to every other event in the spacetime. The specification is a little more complicated than that of Euclidean geometry. In the Euclidean case, there is just one type of distance, that measured by ordinary measuring rods. In a Minkowski spacetime, there are three types of distance, jointly known at "interval" or "spacetime interval."

The simplest is the distance from an event to another that is spacelike separated from it. That is, the second event lies outside the first event's lightcone. The distance is just the distance measured in the familiar way by measuring rods. It is often called "proper distance." (To get a clearer sense of how this measuring operation can be applied to all events spacelike separated from the initial event, we will need to see the spacetime representation of the relativity of simultaneity. That is the topic of the next chapter.)

| In the next case, the second event is timelike separated from the first event. That is, it lies within the first event's light cone. This distance in spacetime is measured by a clock that moves inertially from the first event to the second. The time read on the clock gives us the spacetime interval between the two events. It is also called "proper time." |

Finally, the second event may be lightlike separated from the first event. That is, it lies on the event's light cone. Then the interval to the event is zero; and it is zero no matter where that second event is on the lightcone.

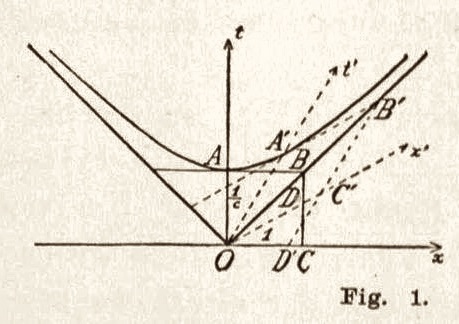

| There is a construction in Minkowski

spacetime geometry that is analogous to the circle of Euclidean

geometry. Once again, we locate all the points

that are one unit, two units, etc. separated in spacetime

interval from our initial event. What results is the figure shown. The dotted lines represent the light cone of the initial event. The curves within the light cone are the loci of points one unit and two units of proper time distant from it. They are hyperbolas that approach the light cone arbitrarily closely. The curves outside the light cone are also hyperbolas. They are now the loci of all points one unit and two units of proper distance from the initial event. Hypebolas are the analogs in Minkowski geometry of circles in Euclidean geometry. |

| Why are the

figures hyperbolas? The reason is easiest to see in the

case of the locus of events separated by constant proper time from

the initial event. The situation physically corresponds to many clocks, as shown in the figure. The first is at rest; the second moves to the right; the third moves more quickly to the right; and so on. The first of these clocks runs the fastest; the second slower; the third slower still; and so on. Hence, as we pass from clock to clock, the clocks will need to travel for successively longer (as measured in the time of the inertial frame) in order for the clocks to count off a unit of proper time. When we draw a spacetime diagram, we recover the figure shown. The motion of the clock at rest in the frame is the shortest, vertical line. The motion of the fastest moving clock is the longest line at the right. They are all a unit proper time in length. Their endpoints trace out the hyperbola shown. The case of the hyperbolas of constant proper distance is harder to analyse. Seeing how the relativity of simultaneity is represented in spacetime in the next chapter is the starting point. It is left as an exercise for the reader. |

These figures have a venerable history in relativity theory. Here is how they appeared in Minkowski's original publications.

Copyright John D. Norton. January 2001, September 2002; July 2006; February 3, 2007; January 23, September 24, 2008; February 3, 2012; February 9, 2013; January 27, February 9, 2015. January 28, 2022. February 1, 2022. January 30, 2024.