| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

Background reading: J. Schwartz and M. McGuinness, Einstein for Beginners. New York: Pantheon.. pp. 1 - 82.

We now take Einstein's special theory of relativity for granted. The evidence in its favor is quite massive, so that there is little license for skepticism. Our real task is to learn the theory and there are many text books that develop it in an easy to understand fashion.

In 1905, however, when Einstein first introduced it, it was a strange and even shocking theory . Then Einstein did not have the luxury of a simple text book on special relativity from which he could learn the theory. Somehow he had to see that such a theory was needed. And then he had to devise the theory and know it was not crazy speculation. How did he do it? That is the present topic--the history of Einstein's discovery of special relativity. We shall see that Einstein had no crystal ball. He worked with resources and methods available to everyone. That is the fascination of the episode. We shall see how he took the same pieces everyone had and assembled a masterpiece where everyone else faltered.

Before we look at Einstein's deliberations, we need to see what came before. That provided Einstein with the foundation upon which he could build the special theory of relativity.

To foreshadow what is to come, we will find that there

was no good experimental foundation for special relativity prior to

Einstein's time. That is, we needed reliable results on things that move

very fast, close to the speed of light, before relativity theory could

have solid experimental foundation. That foundation came with the

electromagnetic theory of Maxwell and others in the nineteenth century. It

gave the first reliable account of how some very rapidly moving things

behave, including, most notably, light itself. Before

Einstein's time, relativity theory could not properly emerge.

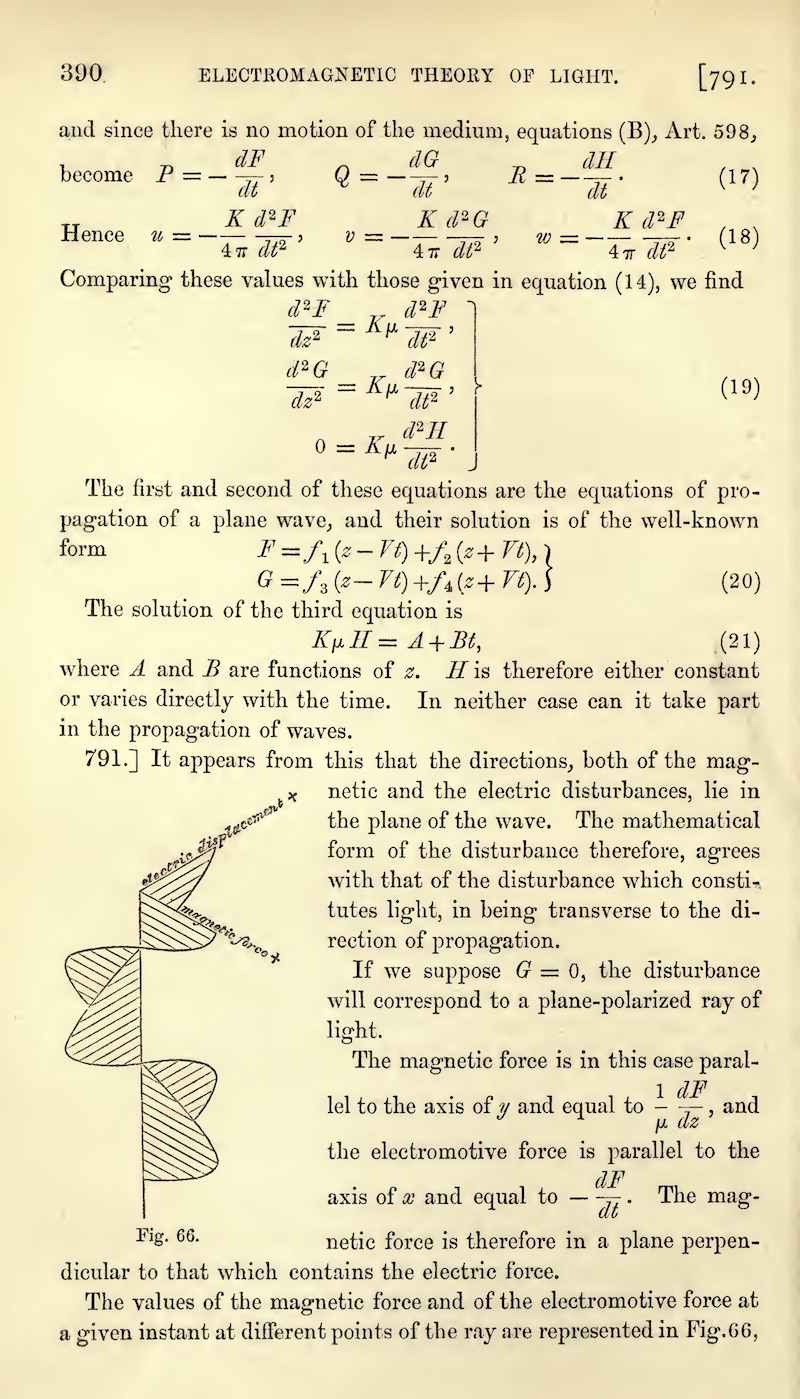

Once electromagnetic theory had been developed, there was a sense that

relativity theory already lived within the theory. H. A. Lorentz already

discovered the basic equations Einstein would use later within special

relativity. It had become inevitable that

relativity theory or something like it would emerge. It was really only a

question of who would have the ingenuity and flexibility of mind to find

the theory first. That person proved to be Einstein.

Nicholas Copernicus |

The principle of relativity tells us that we

cannot detect our uniform motion. Whether uniform motion was

detectible or not became a pressing issue in the sixteenth and

seventeenth century. Up to then, the widely accepted idea was that the earth was at rest at the center of the cosmos. The sun, moon and planets orbit around it. Nicolaus Copernicus had other ideas. Using powerful astronomical arguments collected in his 1543 On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, he urged that the earth is not motionless. Rather, it is the sun, not the earth, that is at the center of the motions of the cosmos. In this heliocentric (sun-centered) cosmology, the earth is just another planet orbiting the sun. In addition, the daily rising and setting of the sun, moon and stars arises not from their motion, but from the daily rotation of the earth on its axis. |

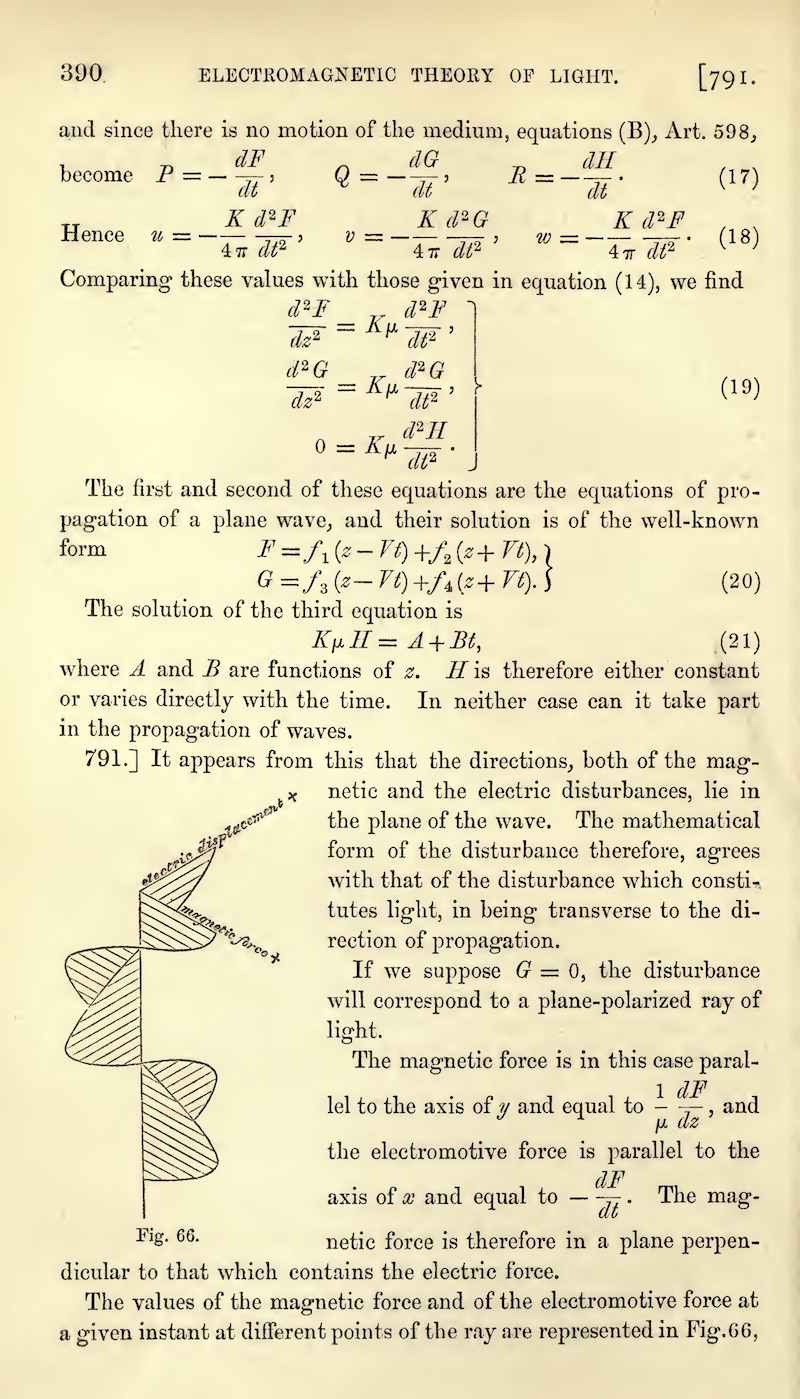

Here's a contemporary (1671) view of the competing

systems. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kircher_-_Iter_extaticum_-_Cosmic_systems_from_Ptolemy_to_Copernicus-edit.jpg |

Earth in the Center Sun orbits |

was replaced by | Sun in the Center Earth orbits |

Copernicus' idea was not new. Until Copernicus, it seemed

unworkable. In the second century AD, Claudius Ptolemy wrote the

definitive account of the geocentric (earth-centered) cosmology in his Almagest.

In it, he had already refuted those who suggested

that earth rotated on its axis by pointing to the great speed such motion

would necessitate for points on the earth's surface:

"...the result would be that all

objects not actually standing on the earth would appear to have the same

motion, opposite to that of the earth: neither clouds nor other flying or

thrown objects would ever he seen moving towards the east, since the

earth’s motion towards the east would always outrun and overtake them, so

that all other objects would seem to move in the direction of the west and

the rear." (Almagest, Book

1, Section 7.)

Copernicus may have had formidable astronomical arguments favoring his heliocentric system. Ptolemy's physical arguments, however, remained as a formidable obstacle for Copernicus' proposal. They could not be ignored.

If Copernicus' idea was to survive, physics would have to be renewed so that the motion of the earth under out feet would be undetectable by physical means. In later language, we needed a new physics that conformed with the principle of relativity. While Copernicus had made some small efforts in this direction, the challenge was taken up most fully by Galileo Galilei. His most mature defense of the Copernicus system came in his 1632 Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. The two systems are the Ptolemaic and the Copernican.

In it, through a dialogue between three characters, Salviati, Simplicio and Sagredo, the merits of the two systems are debated. Needless to say, the Copernican heliocentric system prevails. In the midst of the argumentation, Galileo's representative, Salviati, presents a memorable thought experiment.

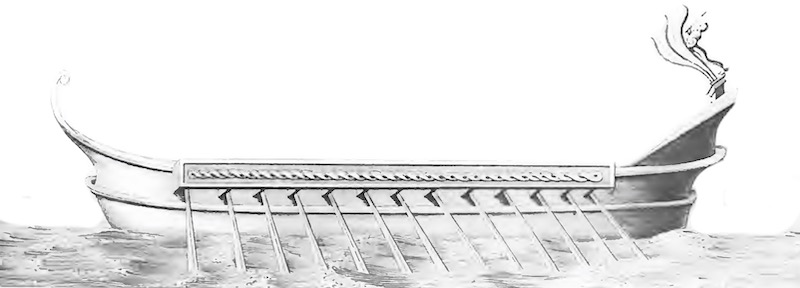

| "Shut

yourself up with some friend in the main cabin below decks on some

large ship, and have with you there some flies, butterflies, and

other small flying animals. Have a large bowl of water with some

fish in it; hang up a bottle that empties drop by drop into a wide

vessel beneath it. With the ship standing still, observe carefully

how the little animals fly with equal speed to all sides of the

cabin. The fish swim indifferently in all directions; the drops

fall into the vessel beneath; and, in throwing something to your

friend, you need throw it no more strongly in one direction than

another, the distances being equal; jumping with your feet together,

you pass equal spaces in every direction. When you have observed all these things carefully (though there is no doubt that when the ship is standing still everything must happen in this way), have the ship proceed with any speed you like, so long as the motion is uniform and not fluctuating this way and that. You will discover not the least change in all the effects named, nor could you tell from any of them whether the ship was moving or standing still..." |

|

Here is the first situation imagined: a ship standing still.

From John Fincham, A History of Naval

Architecture. 1851

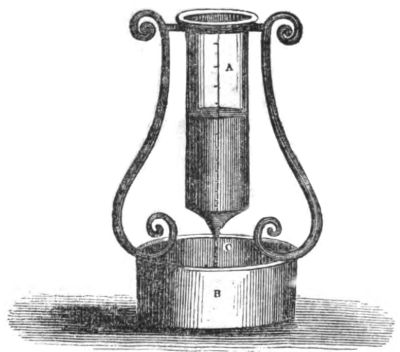

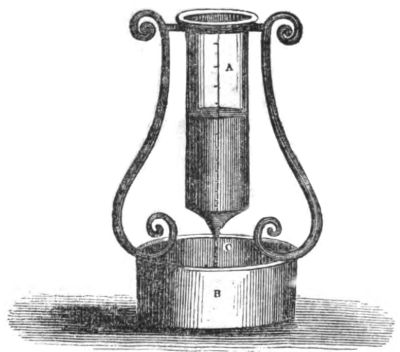

Beneath the decks we imagine all sorts of experiments. They include water dripping from a bottle. That is how a "clepsdrya," a water clock, works. The regular pace of drips measures the passing of time.

The Saturday Magazine, Vol 6, 1835, May 16,

p. 188.

Now we imagine the second situation: the ship moves with a uniform motion.

The same experiments are repeated beneath the decks and, Galileo argues, everything proceeds exactly as in the first case. The water will drip exactly as before. Nothing in those experiments differs and enables the uniform motion of the ship to be detected.

It is easy to see that this thought experiment matches the formulations given for the principle of relativity in an earlier chapter. In particular it conforms with an important consequence of the principle of relativity inferred there:

No experiment can reveal the absolute motion of the observer.

In making his argument, Galileo used as a surrogate for a moving frame of reference, the closest in his readers likely experience: a ship moving at uniform speed on calm seas. If we were to recreate his thought experiment now, we might instead use airline travel. Imagine that you are in the cabin of a airplane cruising in calm air at a great, uniform speed. A convenient surrogate for an experiment is the meal service:

Photo: J. D. Norton, during a transatlantic

flight, 2018.

In place of the water dripping into a bowl, we have the coffee service. Coffee pours into our cup in a manner that is indistinguishable from how it pours when the plane is at rest on the tarmac at the airport. The plane is moving at 500mph, which roughly 733 feet per second. Yet, we have no fear that the coffee, once it leaves the pot, will be left behind, while the plane flies on. In the tenth of a second the coffee needs to fall from the pot to the cup, the plane has moved forward by 73 feet. The coffee is, fortunately, not left behind! Nothing we can do in the cabin reveals the plane's uniform motion.

https://www.needpix.com/photo/download/614285/coffee-cup-pouring-cup-of-coffee-coffee-cup-drink-caffeine-hot-beverage

Isaac Newton  |

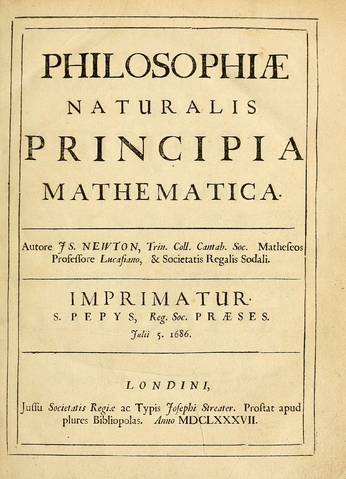

Galileo's work pointed to what the new physics

would be like. The work of developing that new physics was completed

by Isaac Newton in his magisterial Mathematical Principles of

Natural Philosophy of 1687. Conformity with the principle

of relativity was built into Newton's physics from the

outset. To see how, consider a naive physics that arises from casual observation of ordinary things in the world. The default "natural" state of bodies is to be at rest. People, animals and objects do not move unless something makes them move. Those motive powers set things into motion and must maintain their action on the object if it is to keep moving. A cart is moved by a horse and stops moving when the horse tires and stops pulling. Newton's Principia changed this default conception at the outset. The natural state of bodies, according to his first law of motion, is uniform motion in a straight line. If left to themselves, bodies would, to use the later expression, persist in inertial motion. Deviations from inertial motion are due to impressed forces. According to Newton's second law of motion, these forces do not cause motion, but changes of motion. In a more recent formulation, we associate forces with accelerations. These two principles made it possible for Newton's physics to conform with the principle of relativity in the most important aspect: processes we can measure and check run in the same way in all uniformly moving systems. Nothing in them will allow us to pick out the motion of one as preferred. We may be on a rapidly moving earth, but casual observations and experiments will not reveal it. Newton did not write explicitly of the principle of relativity. This focus on it as a principle is a late 19th century and early 20th century innovation. Rather, he built his physics, as we saw in an earlier chapter, on the notion of absolute rest. The principle relativity was respected in the weaker sense that no experiment we could do on the earth would reveal our motion with respect to this absolute state of motion. |

| There was a complication in this last result of

the invisibility of the motion of the earth to terrestrial

experiments. In so far as the earth is moving inertially, no

terrestrial experiment can reveal its motion. Now the earth is very

nearly moving inertially--but only very nearly. The

earth spins on its axis and completes one full rotation in 24 hours.

That means that a point on the earth's surface is moving towards the

east. While this is happening, the direction we call "east" is

continuously being deflected downwards, toward the axis of the

earth's rotation. After 24 hours, the direction we call "east" has

rotated through a full 360 degree circle. This deflection is an accelerated motion to which the principle of relativity does not apply. It can be detected by a terrestrial experiment. Léon Foucault put just such an experiment on public display in Paris in 1851. He suspended a weighty pendulum from a great height in the Paris Panthéon. While the fulcrum of the pendulum is carried along fully by the accelerated motion of the earth's rotation, the freely swinging pendulum bob is less affected and does not fully move with the Panthéon floor underneath. The net effect is that the plane of oscillation of the pendulum is left behind by the floor rotating underneath. Those standing on the floor of the Panthéon, however, judge their floor to be at rest. They find that, over a period of several hours, the plane of oscillation of the pendulum slows shifts. It is an experimental manifestation of the absolute acceleration of the earth. An animation, from wikipedia, illustrates the effect:  https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Foucault-rotz.gif |

|

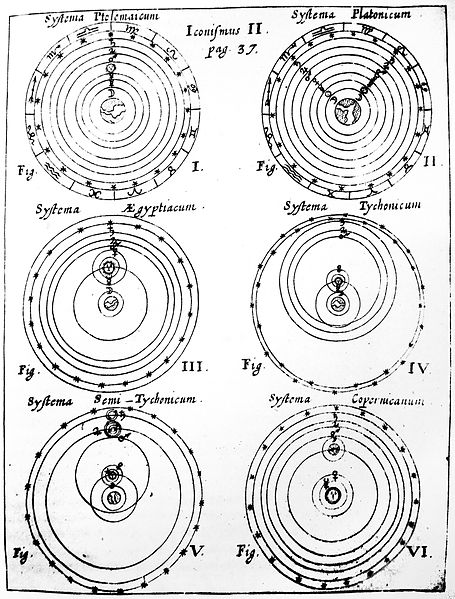

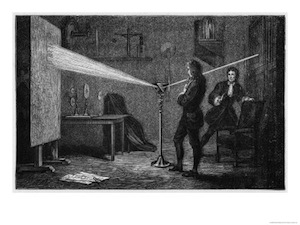

Newton splits light into its component colors |

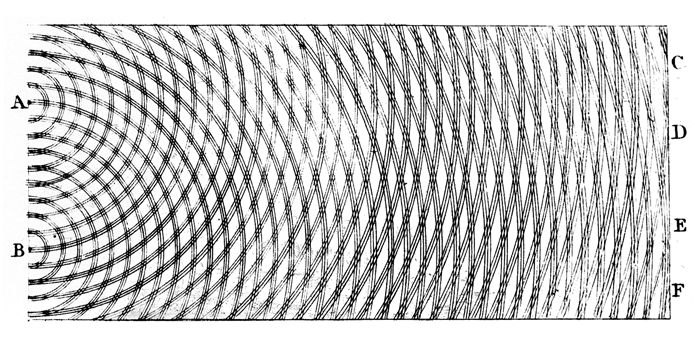

What altered this happy arrangement in the

nineteenth century were advances in the theory of light. Newton

has supposed that light consisted of rapidly moving corpuscles; they

obeyed the principle of relativity as much as anything else in his

universe. Following the work of Fresnel and others early in the

nineteenth century, this account was replaced by one of light as a

propagating wave. One of the most important indications that light was a wavelike process was the discovery of interference effects, shown below in Thomas Young's famous two slit experiment. Two light sources produce the characteristic interference patterns familiar to anyone who has thrown two pebbles into a calm pond. |

If light was a wave, it was assumed that the wave must be carried by some medium, just as sound waves are carried by air and water waves are carried by water. How else could the peak and the trough of two waves annihilate one another to produce the interference patterns if the wave was not a displacement in some medium? That medium was known as the luminiferous (=light bearing) ether. The moving earth was now supposed to be moving through a medium that must stream past the earth, much as water streams past a boat moving through the ocean.

|

This ether now made plausible that our planet's absolute motion might be detectable by experiments on the earth. All we had to do was to seek to see the current of ether flowing past. It proved quite easy to devise experiments to do this. Recall that the ether carries light waves, much as air carries sound waves or water, water waves. So if the ether is flowing past us, that flow ought to be revealed in measurements on light. |

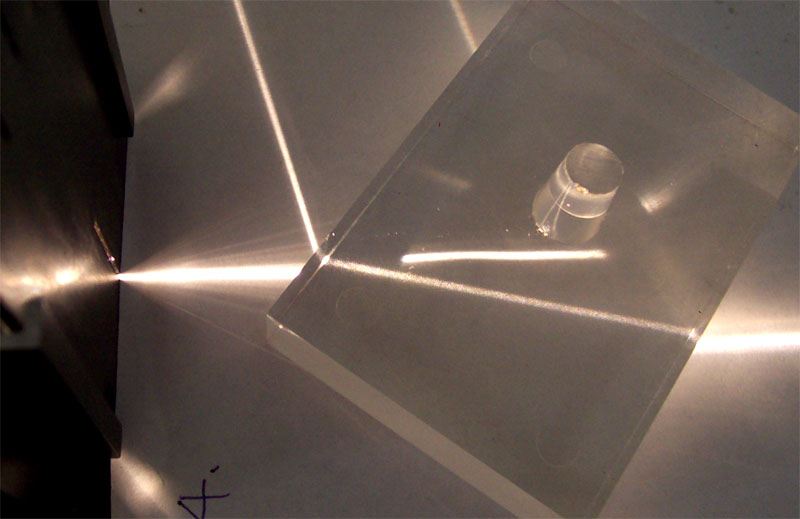

| A series of experiments were devised in the 19th century to detect this ether current. They were experiments on light. Typically they involved the passing of light through a combination of prisms, lenses and the like, creating inference fringes and then looking for an effect in these fringes. The striking result of all these experiments was that the flow of ether had no effect on optical experiments. In that sense, all the experiments failed. Curiously, it was as though the earth just happened to be at perfect rest in the ether. In retrospect, this is a puzzling outcome. At the time, however, there was nothing like the sense of crisis you might expect. Rather it had become a simple regularity of experiment that the ether drift was invisible to us. | In some ways the attitude was not so different from what we now take to be a reasonable attitude to atoms. We know that they are there. Yet at the same time we know that they are so small that no (19th century) instrument will allow us to see them individually. |

| The experiments could be catalogued according to the size of the effect they hoped to detect and, as a result, the sensitivity of the instruments needed. The largest effects were "first order" effects. They needed the least sensitive instruments and were easiest to conduct. Many of these first order experiments were undertaken and all failed to demonstrate an ether current. | Note for the techies who have to know what "first

order" means: First order effects are proportional in size to the

speed of the ether, as a fraction of the speed of light. Second

order effects are proportional to the square of this fractional

quantity. Since this fraction is very small, its square is smaller

still. That means that second order effects are very much harder to

detect than first order effects. Why look at first, then second, then third order effects, and so on? What makes the sequence natural is consider the effect as a function of the fractional speed of the ether wind. After a constant, the first term in the series expansion is the first order effect, the second term is the second order effect, and so on; so that considering these orders exhausts all the possibilities. |

That all first order experiments failed to reveal the earth's motion should, you might expect, have been very puzzling. However it soon ceased to be mysterious. It could be explained by a single hypothesis, the Fresnel "ether drag" hypothesis. It supposed that the ether was dragged partially by optically dense media--the lenses and other media used in optical experiments--by an amount tuned directly to the medium's refractive index. It turned out that amount could be selected so that it would exactly cancel out any possible first order effect of an ether current.

What is the refractive index? When light enters a dense optical medium like glass, it slows down. The refractive index measures the amount of slowing. A refractive index of 1.5, a common figure for ordinary glass, means that light moves at 1/1.5 = 2/3 as fast as light in a vacuum. The greater the refractive index, the more the light is slowed and, as a result, the more the light is bent when it enters the medium.

Here's how the drag hypothesis worked. Light waves are

carried by the medium of the ether, just as water waves are carried by

water and sound waves by air. If the water or the air is moved at some

speed, then that speed will be added to the speed of the water or sound

waves. The same would be expected in the case of light if the ether is

moved. The motion of the ether must be added

to the motion of the light it carried.

| But what does it take to move the ether? Consider

a glass block. Since light waves pass through it, there must be

ether inside it to carry the waves. If the block moves, does the

ether move with it? The simplest case is that it does not. Then, it

is as if the glass block is perfectly porous

sieve that lets the ether flow freely through it. This is the case of no ether drag illustrated opposite. A light wave propagates in the ether of empty space horizontally from the left towards the block, which is moving vertically. The light passes through the block without any deflection from the vertical motion of the block. That is because the ether is undragged; it is left behind fully by the moving block and takes on none of the block's motion. |

| Now take the opposite case. It arises when the ether is fully trapped by the glass block and moves with it, much as air trapped inside a closed car moves with the car. In this case, the ether moves vertically with the glass block, with the same speed as the glass block. As result, the horizontal light wave is deflected vertically with the full motion of the glass block. This is full ether drag. |

| Finally, there are a myriad of intermediate

cases, in which the ether is only partially dragged by the glass

block. In these cases, the glass block acts as a more or less porous

sieve communicating less or more of its motion to the ether. These

are the cases of partial ether drag. In

these cases, the light wave is only partially deflected from its

horizontal motion. Assuming just the right amount of partial drag tuned exactly to the glass' refractive index was enough to eradicate any positive sign of our apparatus' motion through the ether in first order experiments. |

But what is just the right amount of partial drag? And why should it be tuned so precisely to the refractive index of the optical medium? We can see how this comes about if we pursue just one simple experiment that we might try to use to detect the earth's motion through the ether. It is just one experiment. However things work out the same in many other experiments.

| To begin, imagine that we are on an earth that is perfectly at rest in the ether and that we receive light from a distant star that is exactly overhead. That starlight would penetrate a glass block as shown in the figure. The light would descend vertically and keep moving vertically in the block. |

| Now take the same case but add the fact that the

earth we are standing on moves horizontally. In the ether frame of reference, the light will continue to descend vertically towards the block. But what happens to the light when it enters the moving block? The possible effects of the motion of the block on the propagation of the light in the block are shown in the figure. The light in the block may be either undragged, partially dragged or fully dragged. Which trajectory the light follows depends on the amount of ether drag. |

| Now transform our viewpoint to that of the

observer moving with block. The figure shows the same system, just

redescribed by the moving observer. The three possible effects of

the block's motion on the light are shown again. There is a second effect. If we change our point of view to one that moves with the block, there is a corresponding alteration in the light ray outside the block. The vertically propagating light acquires an extra motion opposite to that of our motion. The light that descended vertically in the ether, is now found to descending obliquely as a result of this acquired horizontal motion. This effect is widely recognized in astronomy and was observed in starlight in the 18th century. It is known as "stellar aberration" and is manifested in a slight angular shift in the apparent positions of stars, in coordination with the earth's motion. The effect is familiar. Imagine rain falling vertically. If you drive through the rain in a car, the vertically falling rain will acquire a component of horizontal motion towards you and splash onto the windscreen. |

The pressing question is whether we can use this effect of stellar aberration to determine that we on earth are moving in the ether. That is, can we distinguish this case from one in which we are at rest in the ether and the star is moving towards us with the same relative velocity? We could use this effect to determine our absolute motion in the ether if the incident ray of light differed in any behavior from a ray of light arriving obliquely at the glass block when the block is at rest in the ether.

|

The behavior of a light ray obliquely incident onto a glass block

is well understood from the study of refraction

in elementary optics. The incident ray is bent towards a

line perpendicular to the block's surface. The amount the

refracted ray is bent depends upon the refractive index of the

glass according to Snell's law. The greater the refractive index,

the greater the deflection. |

We see here for the first time something that we will see again. We have an experiment that we first expect to be able to reveal the earth's motion through the ether. We might expect that the light of distant stars would behave differently in optical media that move in the ether. However a second effect arises, partial ether drag, and it exists in exactly the amount needed to cancel out any positive result that would affirm motion in the ether.

Image:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Refraction.jpg

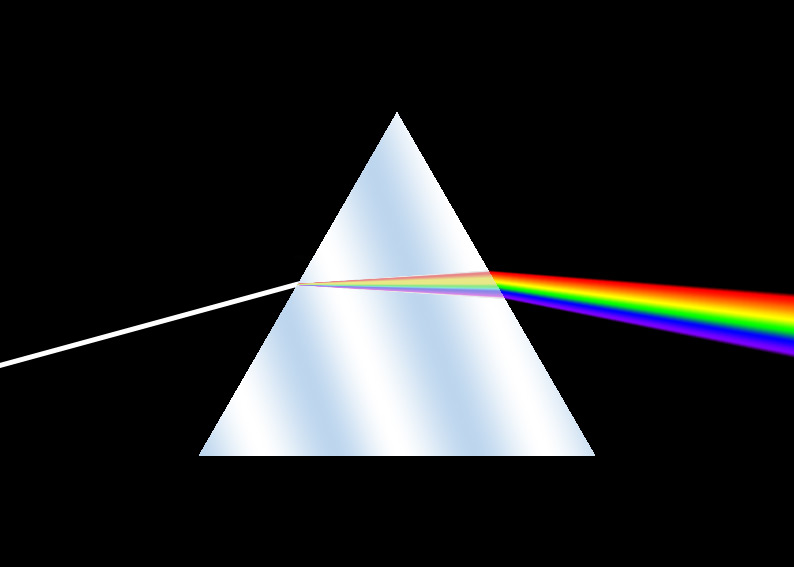

There was a complication. A widely known property of glass is that it refracts light differently for different colors. That is, its refractive index varies with the frequency of the light. This is what enables a prism to split light into its different colors and is responsible for the chromatic aberration of lenses that lens designers try so hard to avoid. The odd outcome of this fact is that light of different frequencies will be associated with different amounts of ether drag, according to Fresnel's formula. In effect that means that each frequency of light has its own ether. That was troubling thought even in the 19th century.

Image:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dispersion_prism.jpg

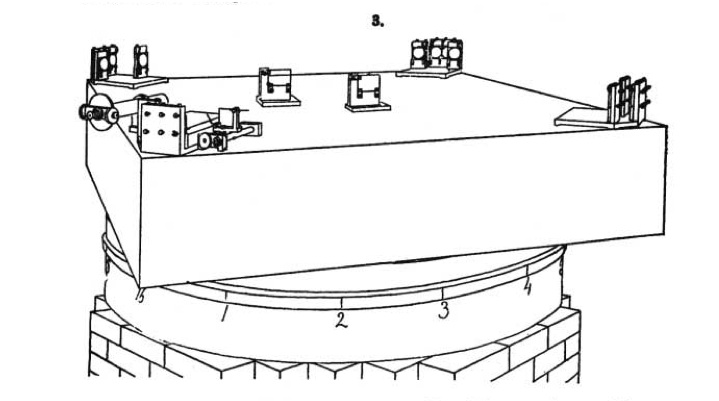

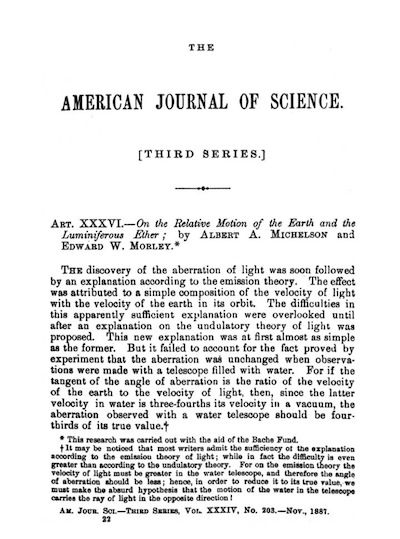

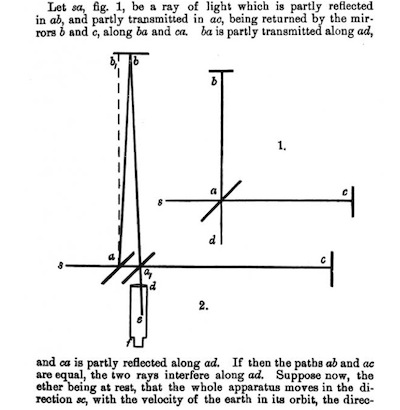

| After first order experiments came second order experiments. These sought to measure the very much smaller second order effects. They needed instruments that were a great deal more sensitive to ether currents; for they had to be able to detect the residual second order effects that might remain after the Fresnel drag had protected first order effects from detection. This added sensitivity meant that second order experiments were a great deal harder to carry out. There was only one successfully executed in the 19th century, the celebrated experiment of Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley of 1887 that completed Michelson's earlier efforts at such an experiment. Indeed the experiment was so difficult that Michelson won the Nobel prize principally for his highly sensitive optical interferometer used in the experiment. | Their original paper is quite readable. |

Pages from Michelson and Morley's paper.

The basic idea of the experiment is that light moves differently on a moving earth according to whether it propagates transverse to the direction of the earth's motion or parallel to the direction of the earth's motion. In the first case the ether current flows across the propagating light, slowing it a little. In the second case, it provides a kind of head wind that slows the light more or a tail wind that speeds it up.

Here is a schematic picture of the way the experiment sought to look for these differences.

A light source sends a beam of light to a half silvered mirror that splits the beam in two. One half continues in the same direction; the other is sent off at 90 degrees. They both strike mirrors at equal distances which reflect them back to a place where they can be viewed. That the mirrors are placed at equal distances from the half-silvered mirror is represented by the two rods of equal length in the figure that connect them.

You can grasp the way the experiment works most simply if you imagine not a beam of light, but merely a pulse of light, as shown in the figure. Since the distances to the two mirrors are the same, the two pulses will require the same time to traverse the distance out and back and they will be detected at the same time.

In practice, pulses are not used. A steady light beam is

used. However the basic analysis remains the same. Each individual peak

and trough in the light beam behave like a single pulse. Any difference in

propagation time will be manifested by the peaks and troughs of the waves

misaligning when they are combined at the detecting screen. The combining

of these two waves produces interference fringes at the detecting screen.

Any change in the alignment of the peaks and troughs is revealed as a change

in the interference fringes.

In use, the apparatus is turned very slowly so that the ether current passes over it from successively different directions. During this turning, the ether current affects the light traveling in the two directions differently and these changes are expected to be manifested as changes in the observed interference patterns.

| Imagine, for example, that the horizontal

direction in the figure below aligns with the direction of motion of

the earth in the ether. Then, thinking classically, we expect the

ether current to slow the travel time of a light pulse making the

round trip in the direction transverse to the ether current. The net

effect of the ether current on the pulse that makes the round trip parallel

to the ether current is an even greater slowing. So, as the

figure shows, by the time the transverse pulse reaches to detector,

the longitudinal pulse is still traversing the apparatus. These difference in arrival times will change as the apparatus rotates and they will be manifested as changes in the observable interference fringes. |

For example, in an extreme case and unrealistic, if the apparatus moves at .866c, then the transit time for the transverse pulse is doubled; and it is quadrupled for the longitudinal pulse. |

The result was negative.

Michelson and Morley found shifts in the interference fringes, but they

were very much smaller that the size of the effect expected from the known

orbital motion of the earth.

The outcome of the 19th century tradition of experiments aimed at detecting the ether current was negative. The wave theory of light of the 19th century depended upon this ether. It was what carried the light wave, just as air carries sound waves. Yet no experiment could show the direction or magnitude of the ether current.

The puzzle was deepened and broadened by the end of the 19th century through the assimilation of optics into Maxwell's theory of electric and magnetic fields. In the 1860's, Maxwell showed that a light wave is really a wave of electric and magnetic fields, an electromagnetic wave. So now the luminiferous ether was also the ether that carried these fields.

How is it possible for Maxwell's electrodynamics to be based fundamentally upon the notion of an ether, yet no experiment can reveal the magnitude and direction of the ether current? This was the problem taken up and solved brilliantly by the great Dutch physicist H. A. Lorentz.

Lorentz first simplified Maxwell's theory into the form that it is routinely taught today. All matter, he proposed, simply consists of electric charges (called "ions" or "electrons") in the empty space of the ether. He then proceeded to show how electrodynamical theory could explain the failure of the experiments to produce a result.

| If an optical medium just consists of such charges, Lorentz could show that an electromagnetic wave propagating through it would be affected in exactly the way Fresnel's ether drag hypothesis required. The ether was not really dragged in Lorentz's account. His was a fixed, immobile ether. Rather the charges that made up the medium were excited by the light wave as it passed through. They absorbed energy from the light and re-emitted it. When the incident and re-emitted light were combined, the net effect was a slowing of the propagation of light that matched exactly the effect of Fresnel's hypothesis. The ether was not dragged; it just looked like it was. The amount that light slowed in media in Fresnel's hypothesis was no longer a supposition but a demonstrated result in electrodynamics. That explained why all first order experiments failed. |

| The second order Michelson Morley experiment was a little harder. There was a solution suggested by the fact that classically light needs more time to make the longitudinal round trip than the transverse one. So what if the apparatus contracted in length longitudinally. Then the longitudinal pulses would need less time to make the round trip and negative result could be restored. The result would look something like this: | The figure shows the extreme and unrealistic case of motion at .866c. The apparatus would have to contract 50% longitudinally. |

| What Lorentz was able to show was that Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism predicted precisely this much longitudinal contraction.To get this result, Lorentz modeled matter composing a body as a large collection of electric charges, all held together in equilibrium by electric and magnetic forces. |

| The equilibrium was disturbed if the entire

object was set in motion. Moving electric charges create magnetic

fields that in turn act back of electric charges. All these changes

settle out into a new equilibrium

configuration. What Lorentz could show was that new configuration

consists in a contraction of the body in the direction of motion in

just the amount needed to eradicate a possible result from the

Michelson Morley experiment. |

| The catch was that matter probably couldn't consist just of electric charges held by electric and magnetic forces. There had to be other forces as well. They had to be there, for example, to prevent Lorentz's electrons blowing themselves apart under the mutual repulsion of the like charges in different parts of an electron. So Lorentz simply supposed that these other forces would behave just like electric and magnetic forces and yield the same result. | This type of reasoning was later

denounced as "ad hoc"; that is an

hypothesis, cooked up specifically to solve one problem, but with no

independent support from anywhere else. For example, an ad hoc explanation of why I cannot find my keys is that an evil key hiding gremlin has hidden them. |

The 20th century opened with the Maxwell-Lorentz theory of electrodynamics as the most successful physical theory of the era. While that theory was based essentially on the existence of an ether, the failure to detect ether currents was no longer a puzzle, but a prediction of the theory. Lorentz showed that the theory entailed effects whose combined import was to make the ether current invisible and the absolute motion of the earth undetectable by us. We might be moving through the ether at some definite speed and in some definite direction. But the physics of electrodynamics conspired to prevent us ever measuring that speed and direction.

At the time this seemed like

a perfectly satisfactory resolution of the puzzle of the failure of all

ether drift experiments. It is only if you know what is coming next that

you find the resolution awkward. Or, if you are Einstein, you see more in

the resolution than others then did.

A final remark: the schematic drawing of the Michelson Morley experiment above may seem oddly familiar. In fact we have already seen its essential content before. The two arms of the apparatus are light clocks. You will recall that we computed the relativistic contraction effect from the condition that moving light clocks, one transverse to and one parallel to the direction, of motion must tick at the same rate. This is the same contraction that figures in Lorentz's account.

Copyright John D. Norton. January 2001, September 2002; July 2006; January 2, 2007; January 21,February 4, 2008; January 15, 17, 27, 2010; May 15, 2011; January 28, 2013. September 10, 2020. January 27, 2022.