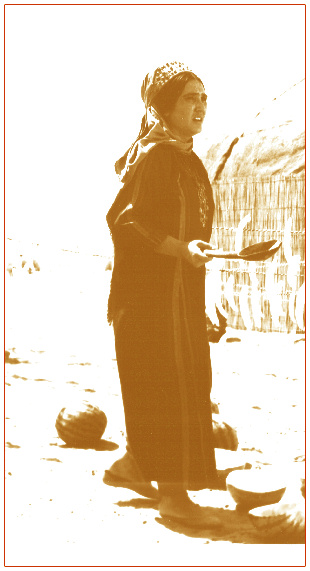

A woman waits in the Turkmen desert hoping for the return of her heroic husband, a pilot in the Soviet Air Force during the Second World War. Pushing aside her fears, she focuses on the tasks of everyday life with h er father-in-law even while realizing that her husband will never return. er father-in-law even while realizing that her husband will never return.

In its representation of Turkmen life at the edge of the desert during World War Two, this film engages a rich genre in Soviet film: the tragedy of lives left on the home front while loved ones sacrificed their lives on the battlefront. Bridging the vast territorial and cultural spaces of the Soviet Union, the sacrifice of war and its suffering was a common theme of Soviet film. The variation rendered in Khodjakuli Narliev’s film highlights these linkages within the Soviet experience.

At the same time, it is clear that viewers witnessed a part of the Soviet Union they had not earlier seen. As a visual experience, the film utilizes rich color to contrast the bleakness of the desert and the sorrow of a war widow. Narliev’s poetic rather than narrative film suggests the influences of Sergei Parajanov’s recent and revolutionary Sayat Nova (1969). With little plot development, the film presents a series of vignettes, flashbacks, and dream-inspired fantasies. The chronological development of the film is confused, as time swirls around bittersweet memories of a lost husband.

The central relationship is between daughter-in-law (Ogul'keiik) and father-in-law (Anna-Aga), one of the least explored relationships in Central Asian culture. Their missing bond is the husband and son, a war hero pilot who never returns from the war; yet their relationship sustains a sense of respect and admiration. When dreams are interrupted by the realities of everyday life, Ogul'keiik demonstrates devotion to the memory of her husband and loyalty to his father.

Anna-Aga: All these years, you have been irreproachable. My son would have been pleased with you. Thank you, you deserve to be happy.

Ogul'keiik: Don’t send me away. I’ll never leave you.

There is some ambiguity in the film’s critique of traditional culture concerning the yashmak (veil). Should the daughter-in-law remove it when she works? How does national tradition interact with Soviet socialism and with Soviet patriotism? Given the fact that this was a relatively contemporary subject, it is striking how timeless and traditional the relationships and their conditions are revealed. Alongside films of the Brezhnev Era of urban renewal or of traditional culture (before the expansion of the Russian Empire to Central Asia) this film undermined Soviet optimism and the image of the depth of Soviet influences.

It is with a sense of irony that we should understand a scene depicting the excitement of modernity and views from the heights of civilization when Ogul'keiik joins her husband on a plane ride before the war. This scene recalling Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa (1927) is just a dream, a mirage, like the Soviet experiment in Turkmenistan.

Written by Michael Rouland

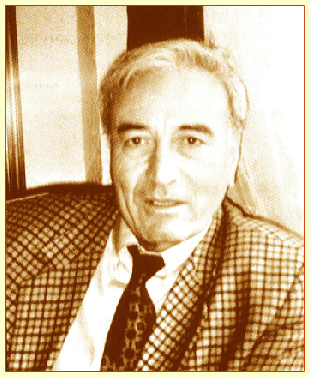

Khodjakuli Narliev graduated from VGIK in 1960. His first filmic breakthrough came when he was the cinematographer of The Competition (with director Bulat Mansurov) in 1963. This film played a key role in the development of Turkmen national cinema. As a director, he made several significant films in Turkmen cinema, including Daughter-in-Law (1972), which is considered to be the single most important Turkmen film. Several of his films confront the question of Turkmen women and their relationship with society and Sovietization, which is present in this film. In recent years he has served as first secretary of the Film Union of Turkmenistan. Khodjakuli Narliev graduated from VGIK in 1960. His first filmic breakthrough came when he was the cinematographer of The Competition (with director Bulat Mansurov) in 1963. This film played a key role in the development of Turkmen national cinema. As a director, he made several significant films in Turkmen cinema, including Daughter-in-Law (1972), which is considered to be the single most important Turkmen film. Several of his films confront the question of Turkmen women and their relationship with society and Sovietization, which is present in this film. In recent years he has served as first secretary of the Film Union of Turkmenistan.

Filmography:

1964: Me and My Brothers (documentary)

1967: Gas in Turkmenistan (documentary)

1968: Three Days in a Year (documentary)

1969: Man Overboard

1972: Daughter-in-Law |

1975: When a Woman Saddles a Horse

1977: You Must Dare to Say No

1981: Djamal's Tree

1982: Karakum: 45˚ C in the Shade

1984: Fragy, Who Was Separated from Happiness

1990: Mankurt |

|

|

This series is co-sponsored by the Center for Russian and East European Studies and the Film Studies Program. It was made possible by the support of the Office of the Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences, and it would not have been possible without the generosity of Forrest Ciesol. |