An invasion begins the film with the defeat of a Turkic tribe. Following the parable of Naiman-Ana established by Aitmatov, the prisoners are rendered into mankurts, suffering death or complete memory loss. The film follows the psychological struggles of one warrior, Yolaman, as he attempts to remember his life until the last memory of his mother is lost.

The legend of the mankurt popularized by Chingiz Aitmatov in his novel The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years ( И дольше века длиться день ), and originally published in Russian in Novyi Mir magazine in 1980, provided a biting allegory for the loss of Central Asian identity and language during the Soviet era. No less resonant today, than when the novel was written or when the film emerged in the early 1990s, the story of the mankurt is a violent reminder that Central Asians should struggle to hold onto their cultural past, traditions, and languages. The legend of the mankurt popularized by Chingiz Aitmatov in his novel The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years ( И дольше века длиться день ), and originally published in Russian in Novyi Mir magazine in 1980, provided a biting allegory for the loss of Central Asian identity and language during the Soviet era. No less resonant today, than when the novel was written or when the film emerged in the early 1990s, the story of the mankurt is a violent reminder that Central Asians should struggle to hold onto their cultural past, traditions, and languages.

A key element of Aitmatov’s initial freedom to write such a scathing novel arose from the fact that he could not be accused of nationalism. He was, in fact, a Kyrgyz writer telling a “Kazakh” story; this was a victory for international understanding within a Soviet literary context. The whole region, of course, felt its deeper significance. And Khodjakuli Narliev’s filmic adaptation only confirmed its resonance across Central Asia. Bringing the story to the Turkmen screen served to establish the legend for all Central Asians as well as to testify to the depth of artistic freedom at the end of the Soviet era.

The literal enemy of the story is the Chinese tribe of the Zhuan Zhuan. China was an easy target for Soviet Central Asians, distrusted for its territorial aspirations and heightened by the Sino-Soviet split. However, the rather pointed attempt to create a narrative space in time well before the arrival of Russian influences and to identify China as the perpetrator of this early enslavement did not hide Aitmatov’s critique of Russian linguistic a nd Soviet cultural influences. By the end of the Soviet era, urban and intellectual Central Asians tended to use Russian as their first language and many felt their traditions were being lost. nd Soviet cultural influences. By the end of the Soviet era, urban and intellectual Central Asians tended to use Russian as their first language and many felt their traditions were being lost.

The legend of the mankurt essentially described how to create ideal slaves by erasing their memories. A raw camel hide, known as the shiri, was divided into several pieces and was stretched over the shaven head of the captured victim. The prisoners were then left out in the steppe without food or water under the blazing sun. If they had not already perished from dehydration or starvation, the drying out of the camel skin created an insufferable pressure on the skull. Of the few that survived this ordeal, the Zhuan Zhuan believed they would create a slave who would never yearn to return home or revolt against his master. Mankurts were given the most difficult and loneliest labor as they had lost all reason and community.

Mankurt was partially filmed in Syria and in Turkey, representing a moment of real promise for the Turkmen film industry as it ventured into the multinational world of film. Unfortunately, these gains of the late-1980s were undermined by political suspicion of film and by its financial neglect.

Written by Michael Rouland

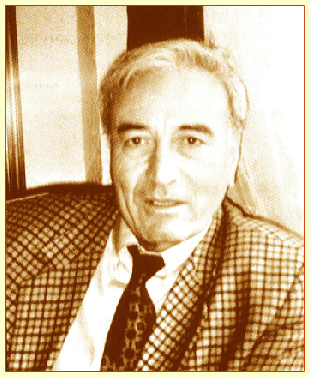

Khodjakuli Narliev graduated from VGIK in 1960. His first filmic breakthrough came when he was the cinematographer of The Competition (with director Bulat Mansurov) in 1963. This film played a key role in the development of Turkmen national cinema. As a director, he made several significant films in Turkmen cinema, including Daughter-in-Law (1972), which is considered to be the single most important Turkmen film. Several of his films confront the question of Turkmen women and their relationship with society and Sovietization, which is present in this film. In recent years he has served as first secretary of the Film Union of Turkmenistan. Khodjakuli Narliev graduated from VGIK in 1960. His first filmic breakthrough came when he was the cinematographer of The Competition (with director Bulat Mansurov) in 1963. This film played a key role in the development of Turkmen national cinema. As a director, he made several significant films in Turkmen cinema, including Daughter-in-Law (1972), which is considered to be the single most important Turkmen film. Several of his films confront the question of Turkmen women and their relationship with society and Sovietization, which is present in this film. In recent years he has served as first secretary of the Film Union of Turkmenistan.

Filmography:

1964: Me and My Brothers (documentary)

1967: Gas in Turkmenistan (documentary)

1968: Three Days in a Year (documentary)

1969: Man Overboard

1972: Daughter-in-Law |

1975: When a Woman Saddles a Horse

1977: You Must Dare to Say No

1981: Djamal's Tree

1982: Karakum: 45˚ C in the Shade

1984: Fragy, Who Was Separated from Happiness

1990: Mankurt |

|

|

This series is co-sponsored by the Center for Russian and East European Studies and the Film Studies Program. It was made possible by the support of the Office of the Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences, and it would not have been possible without the generosity of Forrest Ciesol. |