|

Child and Young Adult Soldiers |

|

Global Perspectives Human Profile Cases: Who Are Child & Young Adult Soldiers? |

|

|

Child and Young Adult Soldiers |

|

Global Perspectives Human Profile Cases: Who Are Child & Young Adult Soldiers? |

|

| To view information about a

particular topic, click on the appropriate heading below.

Common

Profile of Child and Young Adult Soldiers

|

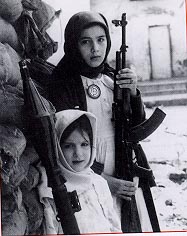

Home |

The number of youth soldiers fighting in conflicts around the world currently is estimated at nearly 500,000. Child and young adult soldiers can range in age from 6 to 18 and can be male or female. Most child soldiers under 15 are fighting for non-governmental military groups. Government forces tend to engage exclusively male recruits, while opposition forces might employ males and females of all ages. Women and girls often provide support services for military groups, such as secretarial, musical, cooking, cleaning, health care, and sexual services. However females are more likely to also serve as soldiers in armed opposition groups. This phenomenon may be even more common in countries where women have been held back from participation in normal society.

Regardless of age, gender, or how they are recruited, child soldiers disproportionately come from the poor and marginalized segments of society, isolated rural areas, the conflict zones themselves, and from disrupted or non-existent family backgrounds. A uniquely disadvantaged sub-group are the inhabitants of refugee camps or internally displaced persons. Displaced persons often regroup themselves by religion or ethnicity making it easy for religious or ethnicity based armed groups to recruit. Recruiters target those groups who are the least able to resist, which often means the most disenfranchised groups. In some cases where age limits are respected, if the recruit can produce documentation of age, he or she can be exempted from service, however, forced recruits are rarely able to do so unless the family can trace their whereabouts. Recruits are often school dropouts or members of street gangs. The flip side is that these same groups who are often the victims of forced recruiting have the most social and economic incentives to volunteer. Lack of education is the primary hallmark of the youth volunteer and military service is seen as an escape from the boredom of formal education. In some cases, though, volunteers are attracted with promises of educational opportunities or overseas travel. Lack of education is even more characteristic of volunteers than of forced recruits.

|

to view special BBC Online Report on Youth Soldiers |

Also, the incentives to volunteer can be even stronger in conflict zones, especially when the conflict and participation in it is viewed as a normal part of life. For example, sometimes family members live in armed camps with their soldier head of household and so it is viewed as normal for the children to join the conflict too. Victims of forced resettlements in conflict zones are also especially prone to seeking membership in armed opposition groups. The recruitment of youth also increases (targeting younger and younger children) in conflict zones due to a competition for manpower, which is always decreasing due to deaths resulting from the conflict. Attempts by governments to counteract recruitment often results in increased volunteering, often due to harassment or a feeling of inevitability of eventual participation. There is also a perception that living conditions are better in armed opposition groups than in government forces. Also, sometimes government forces or armed groups pick up children and youth in conflict zones for humanitarian reasons, and they end up fighting as soldiers.

Perhaps the most at-risk group is children and youth separated from their families for whatever reason. Conflict zones contain a high proportion of such youth. Youth whose fathers have been recruited, detained or killed, illegitimate children, children of single parent families in general, are more prone than their peers to become child soldiers. Unaccompanied children are easier targets and often have no one to advocate for them in any way. Also, families often provide a solid set of anti-war values and often do whatever it takes to protect their children from the conflict, including pressuring them not to participate. Children without families obviously do not benefit from this sort of protection. Youth in this predicament may also volunteer because they are in search of a replacement family unit, which may be provided on some level by the armed group.

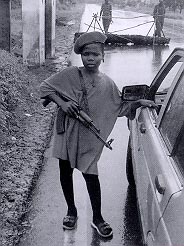

source: UNICEF/Sierra Leone, 1997

There are three basic forms of recruitment described in this section: conscription, forced or induced recruitment, and voluntary recruitment.

|

for Amnesty International stories of youth soldier recruitment |

Forced recruitment is often a response to an immediate shortfall of manpower, either because a conflict or an opposition group is unpopular or because of a high rate of migratory labor. But in some countries there is a long standing tradition of this practice. Certain ethnic, racial, religious, and indigenous groups are often targeted by the government because they are perceived as a threat for their potential to join opposition groups. The most common form of forced recruitment is called press ganging. Press ganging (known as afesa in Amharic) is when an armed militia group or police roam the streets and public gathering places, including school gates, to round up individuals they come across. Another method is to surround and area and force every man and boy to sit or stand together while eligible recruits are selected and taken away. In rural areas, armed groups or government militia will enter a village killing people, raping women, kidnapping children, burning and looting homes. Anyone resisting or not escaping is killed and youth are the least able to defend themselves. Forced recruitment may also be accomplished through intimidation to make it appear voluntary. A government or opposition armed group might enter a village calling for volunteers. Villagers often then report the disappearance of "volunteers" as kidnappings to avoid government retribution for participating in armed opposition groups. Finally, some governments and opposition groups use educational establishments and orphanages as military training grounds.

Voluntary recruitment is when a youth or the family of the youth makes a conscious choice to volunteer for armed service. There are few, if any, known instances of a military group denying participation to underage volunteers. There can be many cultural, economic, social, ideological, and security reasons for volunteering. In some cases, participating in war is glorified by the culture or held up as a sign of masculinity.. Some youth may be persuaded to join by their families to keep them off the streets or because they believe that military discipline is positive for the child. Many illiterate youth believe they will earn prestige or power through military service. Some youth may also be influenced by peer pressure or motivated by a cultural tradition of blood revenge or an obligation to replace a relative who has been killed in action. In other cases, volunteering can occur out of a genuine belief in the cause of the conflict. As mentioned above, youth may also volunteer because they are in search of a substitute family unit, stability, or strong role models or because they are looking for economic security or to satisfy a need for food and shelter. Even where youth regret their decision to volunteer, they often find it impossible to leave an armed group safely. For example, it is not only hard to leave the Sri Lankan LTTE, but it is also nearly impossible for any civilian to leave the northern zone. Even if deserters can make it to the south, they risk being identified and detained by the police, while their family is subject to harassment and threats in the north. Soldiers who merely express a desire to leave are subject to public beatings. The punishment for requesting permission to quit, for example, involves being sent to dig bunkers in areas under heavy shelling, or three to four months of hard labor.

|

to view Human Rights Watch reports on the use of youth soldiers in Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone, Lebanon, and Uganda |

Interviews with former youth soldiers from government forces reveal that they are often treated the same as adult soldiers regardless of their age. Unfortunately the treatment of government recruits of all ages is often poor and inhuman. Government recruits often must endure brutal hazings to break down their resistance and instill fear, which can result in death, suicide, physical and emotional injury. They endure personal physical and verbal assaults as well as training designed to sensitize them to killing. For example, they practice cutting the throats of animals and drinking the blood. Also, they live in an unhealthy environment that might include drug use, drinking, and prostitution. Even though all the soldiers experience such treatment, it can be particularly difficult for children to endure. In some cases, youth soldiers receive harsher treatment and are assigned to the lowest of the military ranks. Hence they are given poor medical care and inadequate food rations, while their young bodies are the least able to withstand such conditions. Some governments which legally recruit under 18s may have special policies related to them, such as less exposure to active service, the provision of recreational facilities, or monitoring by adult support staff.

Treatment of youth soldiers in armed opposition groups is often equally bad. Young soldiers who cannot keep up are often killed in order to ensure their silence. Children are often used as executioners and, in some cases, forced to participate in ritual cannibalism. These acts might include members of the child's own family. There is some evidence of drug and alcohol use and sexual abuse, although this is not universal.

|

to view a report about youth learning to commit atrocities by Elisabeth Janz-Meyer Rieckh |

In armed opposition groups children are typically used in support capacities at the beginning of their service, rather than combat. However, their work is often no less dangerous. Due to their size and agility, children can also be used as look outs, spies, messengers, and porters, eventually engaging in combat when they grow older. The use of children in this manner endangers all children in a conflict zone, as they are all subject to suspicion. There have been reports of governments systematically killing children judged to have been indoctrinated by rebel forces. Such action raises serious questions about government compliance with human rights conventions. According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 37, under 18s should not be executed for alleged criminal acts and are entitled to the right of due process. Adolescents are also used frequently for suicide missions, such as scouting mine fields, and other hazardous assignments. In full scale combat, youth soldiers become casualties easily due to lack of experience, training, and endurance.

|

to read about the experiences of child soldiers in their own words |

Selected information summarized

from the following sources:

Brett, R. & McCallin, M. (1996).

Children: The invisible soldiers. Stockholm: Rädda Barnen.

Goodwin-Gill, G. & Cohn, I. (1994). Child

soldiers: The role of children in armed conflicts. Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

International Save the Children Alliance (1998).

Stop Using Child Soldiers! London: Author.