Time would continue to pass for the smoldering ruins were we and all sentient beings in the universe suddenly to be snuffed out.

John D. Nortonthanks

Center for Philosophy of Science

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

This page at http://www.pitt.edu/~jdnorton/Goodies

"It seemed like a good idea, but I knew I'd regret it when I woke up in the morning."

Download a revised and updated text here.

A common belief among philosophers of physics is that the passage of time of ordinary experience is merely an illusion. The idea is seductive since it explains away the awkward fact that our best physical theories of space and time have yet to capture this passage. I urge that we should resist the idea. We know what illusions are like and how to detect them. Passage exhibits no sign of being an illusion.

We have no clear idea of how to

describe this passage in ways comparable to the precision of theories of time

and space in physics. We usually end up describing passage with metaphors that

prove circular and then, in desperation, gestures. That failure is not a good reason to doubt the objectivity of

temporal passage; it is a reason to doubt the reach of our understanding.

Explaining passage away as an illusion is an instance of a

desperate stratagem that has been used to ill effect elsewhere when we

become too eager to explain away an awkward fact. Immanual Kant urged that the

Euclidean structure of space and the causal character of the world are

illusory, merely arising through the interaction of our sensory apparatus with

the things in themselves. He thereby grounded his defense of the impossible

dogma that we know these facts for certain. Many worlds theorists in quantum

mechanics protect their doctrine by asserting that the most basic fact of

laboratory experience--that experiments have unique outcomes--is an

illusion.

Time passes. Nothing fancy is meant by that.1 It is just the mundane fact known to us all that future events will become present and then drift off into the past. Today's eagerly anticipated lunch comes to be and satiates our hunger and then leaves a pleasant memory.The passage of time is the presentation to our consciousness of the successive moments of the world.

|

Time really passes. It is not something we

imagine. It really happens; or, as I shall argue below, our best

evidence is that it does. Our sense of passage is our largely passive

experience of a fact about the way time truly is, physically. The fact

of passage obtains independently of us. Time would continue to pass for the smoldering ruins were we and all sentient beings in the universe suddenly to be snuffed out. |

This passage of time is one of our most powerful experiences. What is not in that experience is the idea of a present moment, the "now," that has any significant extension in space. The "now" we experience is purely local in space. It is limited to that tiny part of the world that is immediately sensed by us. There is a common presumption of a present moment that extends from here to the moon and on to the stars. That there is such a thing is a natural supposition, but it is speculation. The more we learn of the physics of space and time, the less credible it becomes. For present purposes, the essential point is that the local passage of time is quite distinct from the notion of a spatially extended now. The former figures prominently in our experience; the latter figures prominently in groundless speculation.

The passage of time is real physical fact that obtains in the world independently of us. How, you may wonder, could you think anything else? Well, you might think that the passage of time is some sort of illusion, an artifact of the peculiar way that our brains interact with the world.2 Indeed that is just what you might think if you have spent a lot of time reading modern physics.

|

Following from the work of Einstein, Minkowski and many more, physics has given a wonderfully powerful conception of space and time. Relativity theory, in its most perspicacious form, melds space and time together to form a four-dimensional spacetime. The study of motion in space and and all other processes that unfold in them merely reduce to the study of an odd sort of geometry that prevails in spacetime. In many ways, time turns out to be just like space. |

In this spacetime geometry, there are differences between space and time. But a difference that somehow captures the passage of time is not to be found. There is no passage of time. There are temporal orderings. We can identify earlier and later stages of temporal processes and everything in between. What we cannot find is a passing of those stages that recapitulates the presentation of the successive moments to our consciousness, all centered on the one preferred moment of "now."

At first, that seems like an extraordinary lacuna. It is, it would seem, a failure of our best physical theories of time to capture one of time's most important properties. However the longer one works with the physics, the less worrisome it becomes. We find through success after success that the compass of modern physics grows through the past century to embrace all conceivable spatiotemporal processes. That embrace has long held the motions of tennis balls and the return of comets. It now extends to the transitions of electrons between their energy levels in atoms and on to the earliest moments after the big bang. It even gives precise meaning to the extraordinary ideas that time may have a beginning and an end.

We start to get used to the idea that our theories of space and time are telling us all that can be said about time physically. When we start to believe that, we begin to invert the reasoning. If these theories do not have an objective, factual passage of time, then perhaps it is not something factual after all. Perhaps the universe, in all its spatiotemporal glory, just is. It is extended in spatial and temporal directions, with notions like closer and farther spaces and earlier and later moments. But those moments of time intrinsically possess no special unfolding that would comprise the passage of time.

In this spacetime, we exist as objects extended in space and time. We are world tubes of matter winding through spacetime and interacting with all the processes in it. Part of each of our body's world tubes are eyes, ears and a brain, all busily sensing and interacting and signaling. Then, in a process we understand poorly but which assuredly happens, this physical system delivers news of the moments of time in small, serially ordered doses to consciousness.

The illusion of the passage of time, the story continues, arises from our brain's strict regime of rationing this news to these small doses, all impeccably arranged serially, so that earlier and later are never confused, or at least at most by milliseconds. Nothing in the physical facts of the world requires that the news of the moments must be delivered in this rigid, serial regimen. But something in our neural systems leads to it being so. Whatever that something is, it is universal across all humans. That part of our neural system that rations the news of the moments is the same in all of us. So we all have the same illusion of the passing of time.3

I was, I confess, a happy and contented believer that passage is an illusion. It did bother me a little that we seemed to have no idea of just how the news of the moments of time gets to be rationed to consciousness in such rigid doses. Perhaps, I wondered, could we turn that problem over to the neuroscientists? Then there was the odd implausibility of the whole idea that became harder to suppress.

This is what we are supposed to believe. The world tubes of our brains are embedded in a greater world of four-dimensional spacetime that is open for interaction with it timelessly or all at once or however you want to describe a world in which there is no fact of passage. Yet my world tube and yours and all others like them convey those interactions to consciousness in serial doses.

Most significantly, the delivery of the doses is perfect. There are no revealing dislocations of serial order of the moments. While there may be minor dislocations, there are none of the type that would definitely establish the illusory character of passage. We do not, for example, suddenly have an experience of next year thrown in with our experience of today; and then one of last year; and then another from the present.

There are some minor dislocations, but they not the sort that suggests passage is illusory. They are the sort we would expect exactly if passage were objective, but there were occasional malfunctions of our perception of it. Take, for example, the odd experience we have under anesthesia of no time at all passing between the administration of the drug and its wearing off. That is easily explained in the passage view as a suspension of that part of our neural system that detects the passing moments.

| This world tube is like someone resting comfortably on a sofa. The sofa presses uniformly over the body, whose mind could in principle sense the pressure over the full length all at once. Yet the pressures are communicated to consciousness in a slow series that starts at the feet and marches inexorably up the length of the body to the pillow behind the head; and it is the same for every reclining body, without failure or serious dislocation. The result is that the reclining body and all others like it experience an illusory passage of pressure. |  |

If this sofa parable sounds fantastic, then you should find equally fantastic the same idea when applied to world tubes of brains.

So where does that leave us? It would be convenient for physics if the passage of time were an illusion. But there is something odd in the idea that an element of our experience that is so universal and so solid and immutable is just an illusion. So what do we have to do to show that passage is an illusion? Here we can take cues from the many experiences we know to be illusory.

If I hold out my outstretched fingers nearly touching in front of my face, I will see the illusion that has amused children since the beginning of human time. There, floating in space right in front of my face, is a finger sausage.

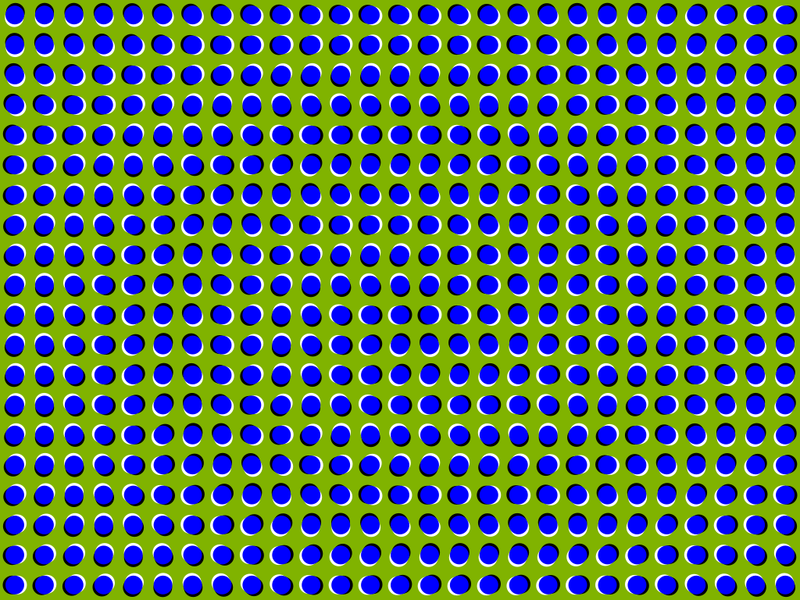

There is an enormous literature devoted to much more elaborate illusions. Here is a remarkable one. When one glances at the pattern below, we see it is animated. It is a seething, boiling surface. But that is an illusion. There is no motion. The image is entirely static.

Image generated by Paul Nasca and released into

the public domain at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Anomalous_motion_illusion1.png

We convince ourselves that both of these are illusions by

two means.

First, we note that, viewing the illusion slightly

differently, it can be eradicated. Merely shutting one eye leads to the sausage

disappearing. Or in the case of the anomalous motion illusion, we can eradicate

the motion in any smaller part of the image merely by covering the rest.

(Indeed I was surprised to find that some people don't even see the illusion of

motion at all!)

Second, we can often identify the mechanism through

which the illusion arises. In the case of the finger sausage, it results

directly from an improper fusion of the images received by each of our eyes. No

doubt similar explication of the anomalous motion illusion is possible in terms

of vagaries of our visual perception. It is striking, for example, that the

illusion is eradicated also merely by fixing one's gaze rigidly on just one

spot of the image. The illusion seems to require both the use of peripheral

vision and the motion of the point of view.

If the passage of time is an illusion, it is quite unlike these familiar examples of illusions. It carries none of the distinguishing marks that enable us to identify other illusions.

First, it seems impossible to eradicate passage from experience in a way that would reveal its illusory character. Indeed there is a healthy tradition in experimental psychology that seeks to generate temporal dislocations in our experience. Subjects hear sounds in each ear that are delivered slightly dislocated in time. Yet they misperceive them as simultaneous. Subjects are lead to misperceive the exact timing of an event they see by hearing cleverly timed audible clicks.

These sorts of experiments are quite successful in leading to dislocations of the order of milliseconds. That sort of dislocation is remote from what one would expect if the entirety of passage is an illusion. With all the tricks at their disposal, why can't an inventive researcher induce dislocations of the order of a day or a year? But if the passage of time is an objective fact independent of our neural circuitry, that failure is no surprise. The greatest dislocation possible would only be the milliseconds of time involved in the neural processing of the moments once they have been delivered to our senses and are routed to consciousness.

Second, what of identifying the mechanism that restricts the delivery of moments to consciousness into the rigid series we experience? In particular, what in the neural machinery blocks us from having perceptions of tomorrow or next year? While neuroscientists have made enormous advances in recent years, I do not think that circuitry blocking this avenue of perception has been identified. But if passage is an illusion of our perception, there must be some mechanism that blocks us perceiving the future.

There are occasions in which our best science requires us to dismiss some fact of experience as an illusion. All our ordinary experience of water and air is that they are perfectly continuous fluids. Yet our best science tells us that is an illusion. On a sufficiently fine scale both have the granularity of molecules. The appearance of continuity is an illusion. But it is one that is readily explicable by the extremely small size of atoms.

|

Again, light appears to us to propagate instantaneously in ordinary experience. Yet it is essential for relativity theory that it have a finite speed of propagation. So we dismiss the appearance of instantaneous propagation as an illusion. Once again, it is readily explicable by the extremely short propagation times needed, which are well below those we can discern in ordinary processes. |

Now consider the passage of time. Is there a comparable reason in the known physics of space and time to dismiss it as an illusion? I know of none. The only stimulus is a negative one. We don't find passage in our present theories and we would like to preserve the vanity that our physical theories of time have captured all the important facts of time. So we protect our vanity by the stratagem of dismissing passage as an illusion.

|

We are not alone in this stratagem. There is a fine tradition of dismissing uncomfortable facts as illusions. Immanuel Kant believed that we knew some of the facts of science with certainty. They included the facts that space is Euclidean and all processes causal. He was brought to see by Hume's skepticism that ordinary inductive exploration of the world could not give this assurance of certainty. Yet he was certain and that certainty needed to be protected. So he applied the same stratagem to protect the certainty of his belief from the fallibility of our epistemic devices. |

That space is Euclidean and processes causal are not facts of the world independently of us, that is, facts about things in themselves. Rather, he urged, they arise through the operation of our sensory apparatus as forms of intuition. This is fancy philosopher's talk for a simple idea: the truths of Euclidean geometry are, in the end, illusions. We have no idea of the mechanism through which these illusions are produced. Any talk of eyes, brains and neurons already presupposes the description of things in space, the very thing we are trying to portray as illusory. Nonetheless we are assured these are illusions over which certainty is possible.

| The many worlds interpretation of quantum theory proposes that, when systems evolve into superpositions, all components of the superposition are equally real. They reside in one or other of the many worlds of the theory. That entails the falsity of one of the most fundamental facts of experimental experience: experiments have definite, unique outcomes. | Ψ |

Public domain image downloaded from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geiger_counter_in_use.jpg |

When we use a Geiger counter to detect whether a radioactive atom has decayed or not, we register a click, according to whether the decay occurred. Either there is a click or not, but not both. In the many worlds theory, both do indeed happen, but just in different worlds. We are to dismiss the apparent uniqueness of the experimental outcome as an illusion. The proponents of the many worlds interpretation are forced to this odd conclusion. For otherwise everyday experience would repeatedly refute their theory. |

We should stop protecting our vanity and admit what is now becoming obvious to me. We have no good grounds for dismissing the passage of time as an illusion. It has none of the marks of an illusion. Rather, it has all the marks of an objective process whose existence is independent of the existence of we humans.

The real and troubling mystery lies in asking what more can be said. Beyond the barest fact of objectivity, it is not at all clear how properly even to describe the passage of time in precise terms. Our usual approach is to employ a metaphor. The term "passage" itself literally means moving, which in turn presupposes change in time. That makes the metaphor circular. The difficulty is that temporal passage metaphors like these are so fundamental to our descriptions that we have none more basic that can be used to describe the passage of time itself.

It gets worse if we seek a description of passage consonant with familiar physical theories. Yet should not an objective property of time admit description by the hugely successful techniques of modern physical theories? The natural candidate is to talk of time passing with respect to some other time. But that is already too much. It introduces an extra time above and beyond the one we use in our spacetime theories. While such a thing is possible, it is a speculation every bit as dangerous as the idea that the now is extended infinitely in space past Alpha Centauri and beyond.

Thanks My thanks for stimulation discussion and reactions to members of the seminar HPS 2675 Philosophy of Space and Time, Spring Term 2009, University of Pittsburgh.

1 Whether and in

what sense time passes is a venerable topic in philosophy. For entries into

this enormous literature, see

Steven Savitt, "Being

and Becoming in Modern Physics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy (Winter 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2008/entries/spacetime-bebecome/.

Ned Markosian, "Time",

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2008 Edition), Edward N.

Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2008/entries/time/.

Do we really have an experience of time passing? Is it something we perceive directly such as when we see the blueness of the sky or hear the noise of the wind? I think we do experience it. To see why, let us break the experience up into two parts.

First, I think it is uncontroversial that we experience time as moments. That is, we experience the present moment directly. We have indirect access to the past through memory and other traces and we have even more tenuous access to the future through predictive methods. We do not experience temporal relations directly. That is, we do not experience directly that last Wednesday's snowstorm was earlier than today's rain shower. We experience today's rain shower and recall the snowstorm, inferring from that their temporal relation.

Second, we do have a direct perception of the changing of the present moment. That is clearest in our perception of motion. For example, consider two bicycle wheels, one rotating and one not rotating. As long as the rotation is not too fast or too slow, we perceive directly which is which and perceive the motion directly. How that comes about is an issue for experimental psychology. My guess is that the important fact will be that our sensed present moment actually lasts some definite time less than a second. During that time, the wheel turns appreciably and we grasp that as a perception of motion.

That we do perceive motion at some primitive level in our experience is supported by the existence of motion illusions. We see the image in the main text move, even though it does not.

This perception of motion is not the perception of the passage of time. However it is part of it. It may well be impossible to give a non-circular definition in ordinary words of such a primitive notion as the experience of the passage of time. However I do think we come close with the idea of the totality of our perceptions of changes underway in the present moment. Even if we are in an environment that it totally static--an empty, noiseless doctor's waiting room--we still perceive our own bodily functions changing, such as our breathing and heartbeat, and even the process of our thought.

Nothing philosophically fancy is intended by "experience" in this context. All that is intended is the ordinary use of the word. There is no claim made that we can divide what we know of the world into two parts: the pure sense data that are somehow prior to cognition and then the inferences we make from them. Indeed it seems incredible to me to that our knowledge or beliefs of the world could be divided so cleanly in this way. At best we can identify things whose experiential contribution is greater; and I urge that our momentary sense of the passage of time has such a large experiential contribution.

2 For a classic, colorful statement of the view that the

passage of time is a myth, see

Donald Williams, "The Myth of Passage," The Journal of Philosophy,

48 (1951), pp. 457-72.

For a recent, able defense of the reality of passage from its many detractors,

see

Tim Maudlin, "On the Passage of Time" Ch. 4 in The Metaphysics within

Physics. Oxford University Press, 2007.

3 While I believe this attitude lies behind much of the

popularity of the idea that passage is a psychological illusion, it is rare to

find the argument spelled out. It is implicit in remarks made by Carnap when he

reported his discussions with Einstein over Einstein's discomfort that physical

theory does not do justice to our experience of the "Now." Carnap remarked:

"...all that occurs objectively can be described in science; on the one hand

the temporal sequence of events is described in physics; and, on the other

hand, the peculiarities of man's experiences with respect to time, including

his different attitude towards past, present, and future, can be described and

(in principle) explained in psychology."

Carnap's remark can only cohere if we assume he believes that physics has

failed to capture the peculiarities of our experience of the Now and that this

failure is permanent.

Copyright John D. Norton. February 15, 18, 2009.