Wind. Wind. Wind.

July 24, 2010

This day was shaping up to be a great day for sailing around the Point. Currents on the rivers were low. There was a mere 10,000 cubic feet per second flowing on the Ohio. That is a current that I'd come to know well as causing little if any trouble. By late morning, the forecast (click) was calling for West South West winds through the afternoon that would rise from 11 to 13 mph. That was plenty of wind. Indeed I hoped that would all the wind I'd see. Any more would just make trouble. That thought proved prescient.

When I wheeled my bike out onto Liberty Avenue downtown and met a blast of hot humid air, I had no doubt that the temperatures forecast in the high 80s had come. Crossing the Allegheny River at the Sixth Street Bridge, I could see the WSW winds blowing straight up the Allegheny River. That direction was confirmed by the flags on PNC Park, visible from the bridge. That was encouraging. Sometimes the buildings on either side can block the wind on this stretch of the Allegheny.

I paused at a few spots along the river to gauge the wind as I cycled farther. Winds were gusting roughly from 6 to12 mph and blowing from the South West. That fitted the forecast, but was more wind than I expected to measure. At the river itself, you expect to measure winds at a little less than the forecast speeds.

By the time I arrived at the Newport marina and rigged my little boat, a new plan was forming. The winds were blowing steadily and strongly from the West, roughly, along the Ohio River. I had, until now, always sailed upstream, so that whatever happens, the current will always carry me home. With winds as steady as these blowing upstream, perhaps this was the day to try sailing downstream to visit Brunot Island. I'd need to tack into the wind to get there. But my ticket home was an easy sail running ahead of these winds.

It was an attractive plan. Downstream has an interesting collection of islands, Brunot being the first. In my runs along the river trails, I'd wondered how I'd fare trying to negotiate them.

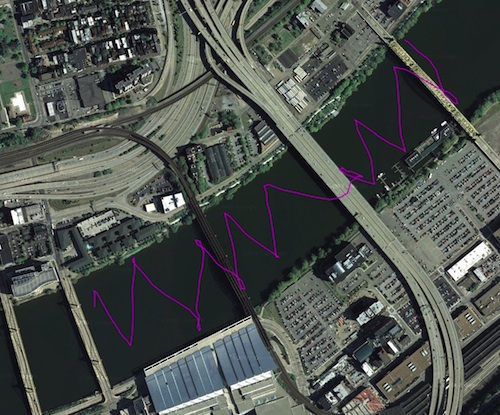

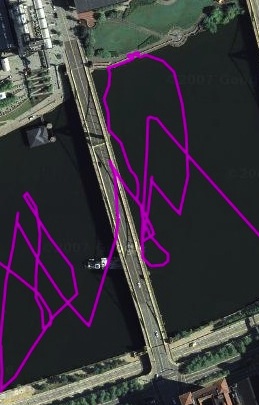

Alas, it was not to be. I'd forgotten that these winds had a Southerly component, so they were somehow making their way around the high hills on the Sourthern shore. That made them unreliable. (Read more) I pulled out into the river and started to tack into the winds. At that instant, the winds died, as if responding to a hidden cue. The GPS plot shows the story:

I set out from the Northern shore, intending to sail up towards Brunot Island, whose tip is just visible, I got halfway across the river when the wind died. I meandered about in a spot nearer the Southern shore, with too little wind to carry me anywhere. A large riverboat from the Gateway Clipper fleet had just sailed past this very spot and would be back shortly. I needed reliable wind to keep out of its way. This was not the day, I realized, to sail downstream. I'd need to wait for North Westerly winds that would blow more reliably down the river. I set my course for the Point.

It was not an easy sail to reach the West End Bridge. This short stretch of river has the most erratic winds. In the time it took me to sail to that bridge, I experienced periods of dead calm and winds from every direction. At one point, a strong gust blew from the North East, exactly the opposite direction of the overall winds. I managed to set my sail to catch it and shot along the river for quite some way with it.

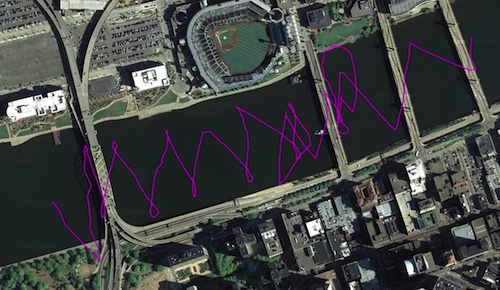

Once I passed the West End Bridge, I was in clearer water. The South Westerly winds took over. I let the sail out and they drove me directly up the Allegheny. With winds this sure, it was my opportunity to sail farther up the Allegheny again. The winds were quite strong, so it was a fast sail. Here's the GPS track of my sail from 1:15pm to 2:10pm:

I covered a lot of river in a short time. Allowing for the delay in getting started, it took perhaps 30-35 minutes to reach the farthest point, the 16th Street Bridge. I dared go no farther since I knew I'd have to tack home laboriously and that would take much longer than my easy run. I was also looking for an easy place to stop and beach.

There proved to be a little rocky beach just upstream of the 16th Street Bridge. I steered into it, jumped out into the river shallows at the edge and hauled my boat over the rocks onto the shore.

Here is the rocky shore:

...and the bridge span overhead

It was hot and I'd worked pretty hard. My water bottle had been calling me for a while, but I had no hands for it. Now finally I could open it. There was also time to dig my lunch out of the hatch. It was modest, a granola bar and a little bag of pistachio nuts, but somehow very satisfying for having been well-earned.

I was weary. Although I didn't know it, the weather (view actual conditions here) was proving hotter than forecast and the temperatures had risen past 90 degrees.

It was time to put back into the water. So I set the rigging and started to push the boat out. Instead of sliding elegantly into the water, it sprang back. I pushed again; it sprang back again. It was as is some river nymph was warning me magically not to enter the river.

Puzzled, I looked up and the mystery was solved. It was not a supernatural event. In beaching the boat, I had tangled the mast in overhead trees. Leaves and little branches fell as I pulled the boat free.

Now I was back in the water. It has been an easy sail upstream and I'd sailed a long way. Now I realized that I was going to pay a price for that ease. The winds on the river were quite strong and stronger than I'd remembered in the sail upstream. I could see little whitecaps forming and a quite substantial chop had developed in the water's surface.

What I did not realize until then was that the wind forecast was wrong. This time it had predicted much less wind than now blew over the river. While I didn't then know the number, the top wind speed had now risen to 20 mph and more, as the record of actual conditions shows. That meant that I was struggling with winds at the river surface that gusted from virtually nothing all the way up to over 20 mph.

It was difficult sailing. I would need to sail all the way home directly into these winds. Sailboats can sail into the wind. They just tack to and fro, as I explained here. But the stronger the wind, the harder it gets.

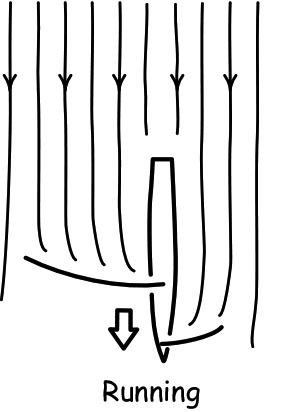

When a sailboat is running, the wind blows from behind it and its sails are let out to catch the wind. The force of the wind presses the boat directly forward.

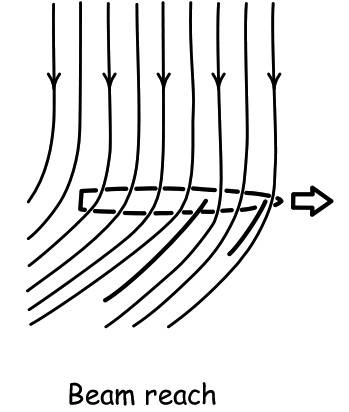

When a sailboat sails across the wind, a "beam reach," the wind blows from the boats side ("beam") and its sails are set to deflect the wind to the boat's rear, so the boat is pressed forward by the pressure of the wind on the sails.

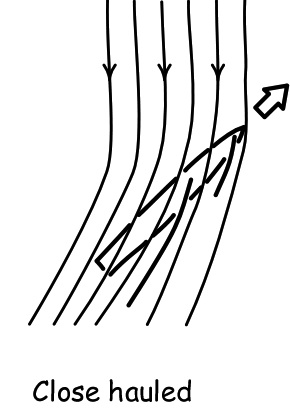

The same mechanism enables the boat to sail into the wind. Here is the configuration for a "close hauled" sailboat, that is one that is sailing a course as close to the wind as possible.

To deflect the wind usefully, the sails are now pulled in quite close to the boat. If they aren't pulled in that close, they would just flap uselessly in the wind.

This need to pull the sails in to make way against the wind is the problem. For now virtually all of the force from the pressure of the wind is directed across the boat and is acting to tip it.

In light winds, this is no problem. In modest winds, the sailor just sits on the windward side of the boat and that is enough to balance things.

In heavy winds, the sailor has to hike out, throw his or her body over the windward side of the boat, to balance the boat. If the winds are steady, that is an exciting part of sailing. The boat flies over the water, while you hover inches from its surface.

In the conditions now prevailing on the river, however, it is an ill-advised maneuver. The winds come in gusts. That 20 mph blast may last one or two seconds or ten seconds; and then be followed by nothing. In those conditions, there is little room for error. If you don't hike out far enough, you won't counterbalance the wind sufficiently. The wind will overbalance the boat and you will end up in the water. If you are hiked out far and the wind dies suddenly, you may overbalance the boat in your direction and end up in the water. Either way, you then have to right the boat in heavy winds, hoping you don't get blown into weeds on the riverbank and that no big boat lumbers down upon you.

As I tacked to and fro into the wind, I took the timid approach. I'd let the sail go with each blast, so the sail would flap uselessly and not tip me. All this slowed my progress and kept me busy on deck, releasing and hauling in the mainsheet (the rope that controls the sail).

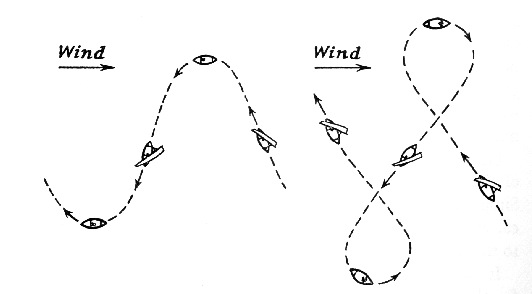

Then there is a second problem. A sailboat makes way into the wind by tacking, that is, zigzagging to and fro across the wind. Each turn is a delicate maueuver. In the middle of the tack, the sailboat is pointing directly into the wind.

At this moment, the sailboat is unpowered. The sail is flapping uselessly. All that keeps the boat moving and turning is its inertia. In heavier winds, that is, in winds over 10mph, I learned that the Bravo is a tough boat to tack. As soon as it has lost wind power, the head wind commonly slows the boat enough so that it doesn't make the turn. If the water is choppy, as it was on this stretch of the river, that compounds the problem. The waves come head on with the wind and their repeated slapping against the hull slows the boat more.

A common outcome is that the tack is missed. The wind blows the boat back and you must continue on the original course, even if there's no more river to sail in. Sometimes the tack can be saved by reversing the rudder as the wind pushes the boat back. The operation is rather like backing up a car. But you must have come close to passing the eye of the wind already for this trick to succeed. In heavier winds, I've found it too little to save most failing tacks.

As I said, this was difficult sailing. Time and again, I was forced to "jibe." Instead of taking the bow across the wind to make the tack, as shown on the left, I'd steer away from the wind and pass the stern through the wind, as shown on the right, making a full 270 degree turn.

It is not an elegant maneuver, especially in heavy winds. The boat takes off rapidly on a run and then, as the stern passes the eye of the wind, the sail snaps over to the other side. You have much less control during jibing. When the winds are heavy, you want more control, not less.

I did what I had to, to get home. Here's the GPS track for the first half hour from 2:30 to 3:00pm:

You can see how often I jibed by the little loops in the track. This was exhausting and difficult sailing. I was constantly reacting to treacherous winds and being shaken by the continual slapping of the chop against the hull. I needed all the space I could get to keep making progress against the wind. Navigating around other boats is usually an interesting diversion. Today it was not welcome. Mostly, the powerboaters sensed my predicament and kept out of my way. I was grateful to them and tried to nod my thanks as we passed.

However it did not always go this way. I was sailing close-hauled just downstream of the Veterans' Bridge when a large power boat approached from downwind on a course that converged directly with mine.

Its skipper, a silver haired, stocky gentleman, stood at the helm

with friends gathered around him. The river was his domain to

command.

He looked straight at me and I looked straight at him. I wondered if

he realized how little scope I had to evade him, short of letting go

the sail to stop dead in the water. He was approaching from downwind,

the only direction I could turn. In any case, the rules of navigation

required him to make way for me. It became clear that he would make

no compensation for me. He just kept looking at me and heading

straight towards my course. Finally, he passed in front of me with a

just a few feet to spare. Fortunately there was not much wake.

A lady seated at the stern smiled awkwardly at me. It might have been an apologetic smile for her captain's misbehavior. Or perhaps she was just puzzled at the oddity of a sailboat on the river. I called out something about the rules of navigation.

"Sailboats under

sail only have the right of way over power-driven vessels unless the

sailboat is overtaking the power-driven vessel or it is approaching a

boat at anchor."

Pennsylvania Boating Handbook. Chapter

4. (Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.)

The next hour of sailing was the most difficult. I made rather less progress than at any other time. The GPS track shows that I made it only just past the Fort Duquesne Bridge. The time is 3:00pm to 4pm:

I was growing weary of letting out the sail with each gust, of the flapping sail, of hauling in the sheet again. It was time to "reef" the sail. The sail of the Hobie Bravo is roller furled. That means it rolls around the mast. It can be "reefed," that is, reduced in size, merely by rolling up part of it around the mast. I'd already reefed the sail in my initial leg upstream as I ran before the wind. It was easy to do. There's a blue furling line wrapped around the mast and all you need to do it pull on it, if you can find a free hand and reach to the front of the boat.

Reefing the sail would reduce the likelihood the the wind tipping the boat, so it started to look attractive. The final straw came when I missed a tack under the 6th Street bridge and sailed into the Southern bridge piling. It was not a major collision. It was just a little bump. Seeing it coming, I held the bow towards the wind so that the boat moved very slowly. Then I pulled the furling line to roll up the sail completely. I let the wind blow me back upstream. Once clear of the bridge piling, the wind on the mast was enough to turn the bow upstream. I let out just a foot or two of sail and sailed slowly across the wind to the dock. There I moored and took a short break. That maneuver and the return to the river from the dock makes the big loop in the GPS track:

Here is the boat docked:

..and another photo.

The sailing was less tense with the sail reefed. I could even "cleat" the mainsheet. That is, I could lock it in a clamp that is part of the block (pulley) through which it runs. That meant that I didn't have to hold back the tension on the sheet. You would not normally do that in heavy winds, since you have to be able to release the sheet instantly if there is a big gust of wind.

The bad side of a reefed sail, I soon found, is that it makes tacking in heavy winds even harder. A reefed sail provides less drive to give you the inertia to pass the eye of the wind. Also, in this case, the sail is so cut that when reefed it is no longer shaped optimally to let the boat sail close to the wind. I was now sailing slower and further off the wind. I had no choice but to jibe.

Here's the last leg of my voyage, from 4:00pm to 5:pm:

I made much better progress than in the hour before. There was much less chop than there had been higher up the Allegheny. Shallower waters produce higher waves. I wondered if that is what was making the difference. However it was not all plain sailing. Each little tangle in the GPS track represents a shift of wind that left me sitting momentarily without motion trying to figure out where the wind had gone. Indeed the wind continued to be variable all the way home. For a while, the wind seemed to die off to a slight breeze. Then I sailed with the sail fully unfurled, until the heavier gusts returned.

When I passed the West End Bridge, I found the wind blowing through the valley and spilling Eastward toward home. (I'd now come not to be surprised by this--see here.) I took the winds for an easy run back. At the last moment, just as I was about to turn into the dock, a sudden gust nearly spilled me into the water. As I hauled the boat out of the water and unrigged it, I noticed that now the winds were blowing steadily in an Easterly direction, the exact opposite of how they blew at the start of the sail. A few minutes later I looked at the small flags on the docked boats. Now they had the winds blowing from the West. In this stretch of the river, when the winds have a Southerly component, you can take nothing for granted!

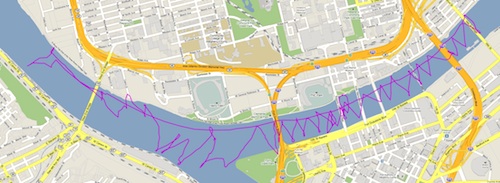

Here are the full gps tracks:

Finally, the plot below is color coded for speed. Note that the legend is in kilometers per hour. I'd estimate that the plot records a maximum speed of 14 km/hour. That corresonds to around 9mph and that is the maximum speed I'd noted by glancing at the GPS receiver as I sailed.

I was really quite exhausted after this sail. It took some effort to unstep the mast and stow all the gear. Finally I was heading off home on my bike. I stopped at various points to measure the wind (at the casino, at the pier at the Del Monte building, on the Sixth Street Bridge). I measured winds varying from 5mph to just over 20 mph in sudden gusts. That fitted with the report of actual conditions, near enough.

While I was exhausted from a mighty struggle with the wind and water, the rest of Pittsburgh was feeling quite festive. There was a Pirate's baseball game starting up. The riverfront was lined with boats and a river ferry had just arrived, disgorging a crowd.

It was after 6pm by the time I had my bicycle stored away and

could sit down to see the latest weather report: 92 degrees! No

wonder I was worn out. But I wasn't quite worn out. So I put on my

running shoes and returned to the river trail for a 45 minute run up

to Herr's Island (now Washington's Landing) and back. I've decided

that I'm a triathlete of a lesser sort. These days are a triple

event: sailing for four hours; cycling four miles; and running forty

five minutes.

John D. Norton

Back to main