| HPS 2103 | History and Philosophy of Science Core Seminar | Spring 2022 |

Back to course documents.

The Idea of a Scientific Revolution

The defining event in the ascendance of history and philosophy of science in the mid 20th century was Thomas Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions. It recommended that we pay serious attention to the history of science carefully if we are to have a philosophy of science that truly reflects our science. Kuhn's volume brought us the distinctive notion of the paradigms of normal science and the revolutions that connect them. It proved to be one of the most influential works in the humanities of the 20th century.

Kuhn's work became the best expression of these ideas. However they can be found in related form in the works of others of his time and earlier. Kuhn reported reading Fleck's then quite obscure Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact and finding its ideas stimulating. Fleck's notion of the thought collective is comparable to Kuhn's notion of a paradigm.

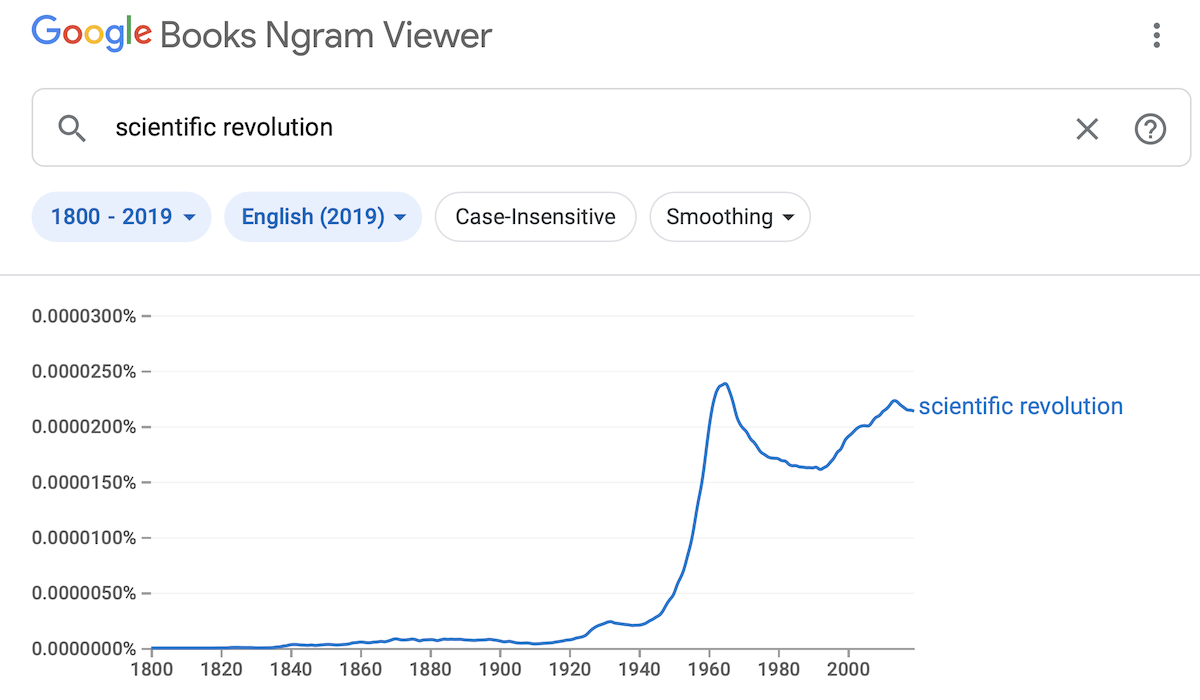

The focus on the idea of scientific revolutions is also a novelty of the mid 20th century. While the term appeared sporadically in the years prior, it enjoyed an explosive growth in the mid 20th century, as this ngram shows:

Until then, the term "revolution" was most commonly used in the political context. The energized interest in its use is usually attributed to Herbert Butterfield's Origin of Modern Science: 1300-1800. Butterfield's main interest was political history, so the use of the term was likely unremarkable to him. The term "scientific revolution" appears 78 times in his volume.

At the same time, Alexandre Koyré's close examination of the work of Galileo and other figures in this period reinforced the idea of the period as harboring a momentous shift in science. Koyré also frequently used the term "revolution" and located in its core in a change of ideas.

While the idea of scientific revolution was taking hold in the mid-20th

century, Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions assured that

it took a central position. In study after study, it is listed as

the most cited work in a relevant reference class. A recent citation study

using Google Scholar places it as number one among the most-cited books in

the social sciences.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/05/12/what-are-the-most-cited-publications-in-the-social-sciences-according-to-google-scholar/

Its 81,311 citations is more than twice those of Marx's Das Kapital

(40,237) and Smith's The Wealth of Nations (36,331).

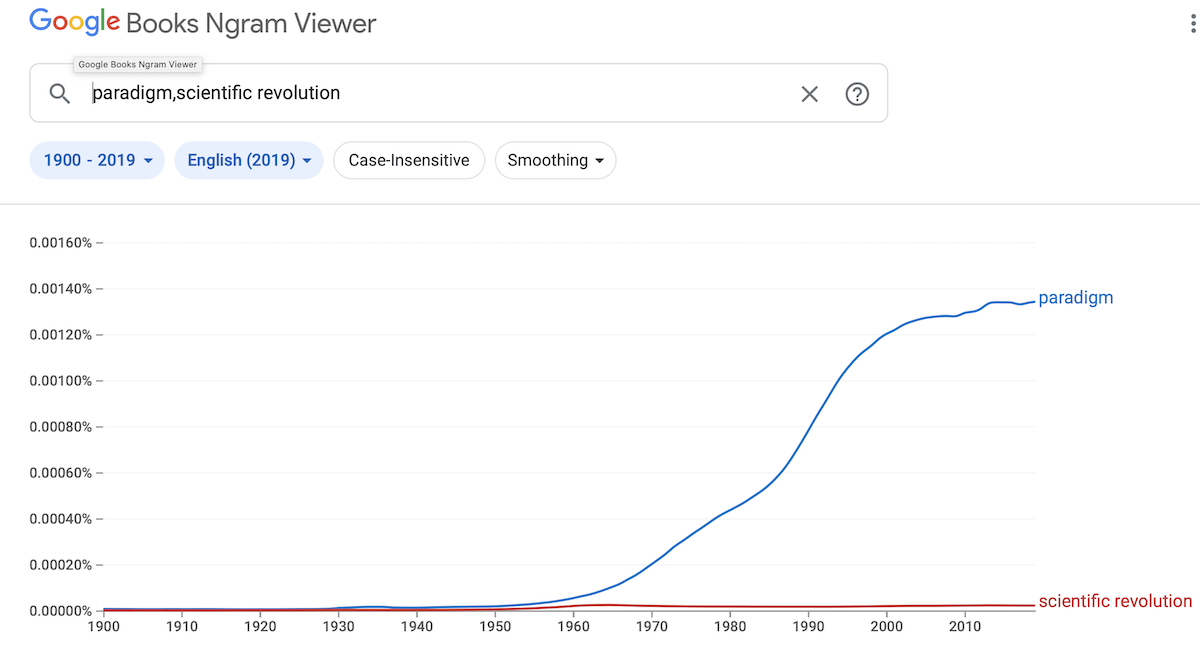

Kuhn's work introduced the term "paradigm" to a wide audience. He extended its rather prosaic meaning of a pattern or model to a term of art in his account of scientific change. The rise of the use of the term corresponds to the publication of Kuhn's Structure in 1962, as this ngram indicates:

A comparison of the occurrence of the terms "paradigm" and "scientific

revolution" in the ngram plot suggest that the popularity of the term

"paradigm" extends well beyond its application in history and philosophy

of science, where is used in the discussion of scientific revolutions.

Kuhn's work attracted considerable attention for what many found to be a relativist and radically skeptical view of science, even though Kuhn denied that this relativism was his intent. The response to his work was massive. Some celebrate the relativism that could be read in Kuhn's writing. Others sought to recover a rational process behind the revolutionary changes in science. The writings of Imre Lakatos and Larry Laudan fall into this latter category.

The association of the term "revolution" with change in science extends well before its surge in popularity in the mid 20th century. I. B. Cohen provides a rich and detailed history of it in his "The Eighteenth-Century Origins of the Concept of Scientific Revolution," Journal of the History of Ideas, 1976, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1976), pp. 257-288. (Thanks for Marian Gilton for the reference.) He describes how the association emerged in the course of the eighteenth century. The original meaning of "revolution" simply as a cyclic process took on the cataclysmic, political connotations with its use to describe the English "Glorious Revolution" of 1688.

A striking use of the revolution language prior to Kuhn can be found in Hans Reichenbach's short volume from 1942, From Copernicus to Einstein. New York: Philosophical Library, 1942. He wrote (pp. 29-30):

It seems that progress in the knowledge of nature can be made only through conflict between two successive generations. What is considered at one time as a revolution of all thinking, a tempest in the brain, is for the next age a matter of fact, a school knowledge acquired under the influence of one's environment and believed and proclaimed with the certainty of everyday experience. Thus, possible criticism to which even the greatest discoveries should be continuously submitted, is forgotten; thus we lose sight of the limitations holding for the deepest insights; and thus man forgets in his absorbing concern with the particulars to re-examine the foundations of the whole structure of knowledge. We shall always have to depend on men like Copernicus who question obvious matters and whose critical judgment penetrates deep into the foundations of truth.

This passage reads to me much like a description of Kuhnian revolutionary paradigm change, but with Kuhn's excessive pessimism replaced by Reichenbach's optimism.

Einstein 1905, The Special Theory of Relativity

Einstein's special relativity of paper of 1905, "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," might well be the most famous scientific journal article in the modern literature. It initiates the modern tradition in physics that overturns the certainties of classical physics. As a result, it has attracted enormous attention in the HPS literature. Einstein's kinematical narrative played a strong role in this attraction. He submerged what was actually a complicated and abstruse problem in electrodynamics in a simple and enormously appealing narrative about clocks, the their synchronization and astonishing idea that the absoluteness of simultaneity fails. If one sees only that simple narrative, one sees only a tiny part of the story.

To tell the story of "how Einstein did it" has had tremendous appeal. There are many accounts that what he did and why it was or was not a rational way to proceed. What we should look for in the readings is how prior presumptions in philosophy of science dictate how the history is written.

Holton's paper addresses the tradition that sees major discoveries driven by experiments.

Zahar's analysis fits Einstein's work into Lakatos' methodology of research programmes.

The difference in the style of writing between Holton and Zahar's papers is notable. Holton's writing is that of a historian who is placing a premium on closeness to his sources. His claims are supported by copious quotes, materials from the Einstein archive and careful checking of the accuracy of translations. Zahar's writing is that of a philosopher who places a premium of precision of the concepts employed. It is not enough to identify an hypothesis as ad hoc. Three senses of ad hocness are carefully defined. Compared to Holton's paper, Zahar's has a looser connection to the historical sources. Compared to Zahar's paper, Holton's is less precise in his philosophical terminology. While the term ad hoc is much used, it is never precisely defined.

There are many other approaches. It is easy to imagine that Einstein's discovery was the result of armchair musing on clocks or merely the boldness of someone willing to undertake a crazy idea. In my (Norton's) paper, I give a brief explanation of the failure of these oversimplified accounts. In my view, Einstein's special theory of relativity was driven by discoveries in 19th century electrodynamics. The theory was there already in the electrodynamics. It just needed someone to realize that the odd effects arising in the electrodynamics were not ultimately electrodynamic effects, but reflections on the unexpected properties of space and time. In short, until the electrodynamics was in place, special relativity could not emerge; and after the electrodynamics was in place, nothing could stop it.

Gravitational Waves, the Sociology of Scientific Knowledge and the Experimenters' Regress

The Collins-Franklin debate over the experimenters' regress, in the context of Weber's work on gravitational waves, illustrates two different approaches methodologically: the sociological and the philosophical analysis of some episode in the history of science.

Applied to Weber's work on gravitational waves, the experimenters' regress is (Collins, 1985, p. 84):

"What the correct outcome is depends upon whether there are gravity waves

hitting the Earth in detectable fluxes. To find this out we must build a

good gravity wave detector and have a look. But we won't know if we have

built a good detector until we have tried it and obtained the correct

outcome! But we don't know what the correct outcome is until ... and so on

ad infinitum.

The existence of this circle, which I call the

'experimenters' regress', comprises the central argument of this book.

Experimental work can only be used as a test if some way is found to break

into the circle."

Collins' analysis is sociological.

In order to ascertain whether the experimenters' regress is present, he reports what various scientists said to him in interviews. Notable elements in reports would be that the scientists vary in their opinions, or that they perceive various elements to have different importance, and so on. What is absent is an assessment of which if any of these remarks are correct appraisals of the import of the evidence.

Franklin's analysis is philosophical.

In order to ascertain the cogency of the physics community's rejection of Weber's claims, Franklin examines the content of the arguments present in the published literature. His focus is the cogency of the arguments presented, the cogency of the objections that were raised and how each side in the debate sought to parry the other. There is no sustained analysis of the social relations among the participants.

Which is the appropriate method? It all depends on the goal.

If the goal is to understand the sociology of the scientific community, then the goal is sociological. In this case, Collins' focus on interviews and his personal contact with the participants is likely to be more revealing. Franklin's analysis focuses on the polished and sanitized arguments presented in the published literature. They are unlikely to reveal the deeper, sociological relations and processes within the community

If the goal is to determine the cogency of evidence claims, then the situation is reversed. The goal is philosophical and requires an assessment of the strength of various evidential claims. The sociological relations among the participants and their off-the-cuff remarks in informal interviews are at best poor representations of the polished argumentation they provide in a published paper. If the cogency of the arguments for the evidential claims is to be assessed, this where they are presented in their strongest form.

The experimenters' regress is a claim in philosophy of science.

It is the claim that a circumstance can arise in which a logical circularity precludes us getting good evidential support for some experimental result. It follows that the sociological method is not the appropriate method to use. If we are interested in the cogency of relations of inductive support, we have to study the cogency of relations of inductive support. Reports on interviews with scientists can only help us indirectly and then only if we pursue the content of their various claims of cogent support or its failure.

One might wonder why Collins would persist in using an inappropriate method.

There are clues in the text. He is a skeptic about scientific discovery. He regards discoveries in science as merely the result of conventional agreements among scientists: (Collins, 1985, p. 100):

"To talk about 'discovering' such things is disingenuous; one should rather talk of establishing or 'negotiating'."

That is, his analysis is predicated on a philosophical thesis about the activity of physicist: they do not discover. In so far as that prior thesis is correct, then he would be justified in conceiving of physicists' claims of evidential support as mere rhetorical maneuverings. There would be no point in examining the cogency of the arguments since, by supposition, that is not what decides the communal outcome.