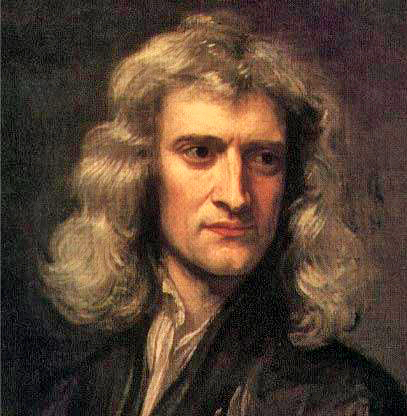

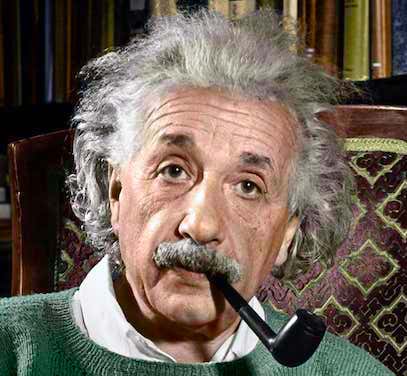

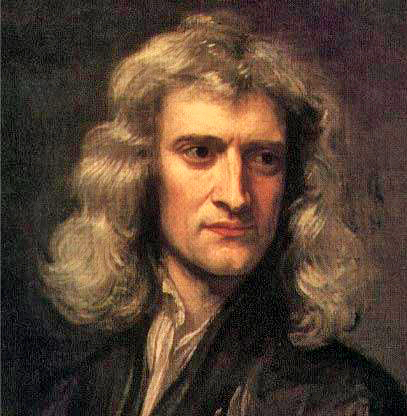

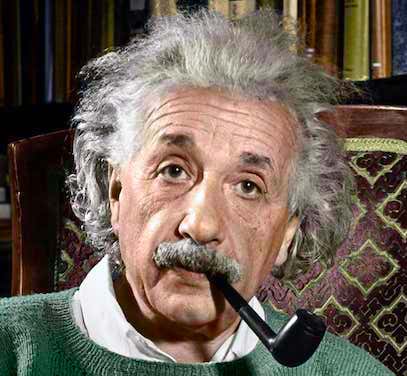

Einstein in 1916, just after his completion of the general theory of relativity .

| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

Background Reading: J. P. McEvoy and O. Zarate, Introducing Stephen Hawking. Totem Books. pp. 9 - 46.

Einstein in 1916, just after his completion of the general theory of relativity . |

The special theory

of relativity was a first step for Einstein. The fuller development

of his goal of relativizing physics came with his general theory of

relativity. That theory was completed in its most important elements

in November of 1915. By many measures, the special theory was a

smaller achievement. Its final creative phase took Einstein some 5

to 6 weeks. Of all the new theories of 20th century physics it is

usually regarded as the most conservative. Had Einstein not

published the theory in 1905, we have good reason to think that it

would have emerged in one form or another. Both Lorentz and Poincaré

had developed the essential equations; they just put a different

interpretation on them than did Einstein. |

| The general theory of relativity took seven years of work by Einstein, the final two to three being years of intense and exhausting labor. No one else was even close to Einstein's ideas. Had he not worked on them, they would most probably not have emerged then. We may not even have them today. In some ways, Einstein's theory is conservative. It is the last "classical" field theory in the sense that "classical" can mean "non-quantum." In another sense, it is anything but conservative. The theory is quite different from any theory before or after. It treats a force by means of geometry and eventually leads to startling notions: black holes, other universes and the bridges to them and even the possibility of time travel. All other theories of forces have been readily swept into quantum theory. General relativity has resisted and the problem of bringing general relativity and quantum theory together remains one of the most difficult, outstanding puzzles of modern physics. | 1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912 1913 1914 1915 |

Before we start to delve into the theory in greater detail, we should just state its basic idea. The theory is based on a single, luminous, dominant idea.

| In Newton's classical account of gravitation, the earth wants to move inertially, that is, uniformly in a straight line. A gravitational force from the sun deflects it and causes it to move in an elliptical orbit around the sun. | In Einstein's theory, the presence of the sun disturbs--that is, curves--the very fabric of space and time. The earth then merely moves inertially in this new disturbed spacetime. It follows an inertial trajectory, but that trajectory has been distorted so that it ends up as an ellipse in the space around the sun; or, more precisely, a helical trajectory winding around the sun's worldline in spacetime. |

|

|

|

General relativity combines the two major theoretical

transitions that we have seen so far. These two transitions are depicted

in the table below. The first is represented in the vertical direction by

the transition from space to spacetime. We

learned from Minkowski that special relativity can be developed as the

geometry of a spacetime. The analogy is quite close. The trajectories of

bodies in inertial motion are straight lines in spacetime in the sense

that they are curves of greatest proper time, that is, timelike geodesics.

That makes them the analogs of the straight lines of Euclidean geometry,

which are also called geodesics, the curves of shortest distance.

The second transition is represented in the horizontal direction in the table. It is the transition from flat to curved geometry. In the context of ordinary spatial geometry, that transition takes us from the venerable geometry of Euclid to the geometry of curved surfaces of the nineteenth century. In the context of spacetime theories, that same transition takes us from the geometry of a flat spacetime, the Minkowski spacetime of special relativity, to the geometry of the curved spacetimes of general relativity. The central idea of Einstein's general theory of relativity is that this curvature of spacetime is what we traditionally know as gravitation.

| Flat geometry | Curved geometry | ||

| Space | Euclidean geometry | |

Non-Euclidean geometry |

| Spacetime | Special

relativity (Minkowski spacetime) |

General

relativity (semi-Riemannian spacetimes) |

This makes learning Einstein's general theory of relativity much easier, for we have already done much of the ground work. The mathematics needed to develop the theory is just the mathematics of curved spaces, but with the one addition shown: it is transported from space to spacetime.

There is a great deal more that could be said--and some of it will be. Einstein himself gave a rather detailed account of the theory as generalizing the principle of relativity to accelerated motion. In first approaching the theory, I will say little about that. I will take you along a different pathway that avoids many of the unnecessary pitfalls of Einstein's account. The problem is that, in retrospect, it is very far from clear just how that generalization was brought about or even if it was done at all. For some details of these problems see the later chapter, "The Relativity of Accelerated Motion." So let's concentrate on curvature. The royal road to curvature is geodesic deviation.

Let us recall how geodesic deviation allows us to detect the positive curvature of a spherical surface.

| A number of observers all start at the equator of a sphere. They proceed in the same direction, due North. As they proceed, the paths converge, eventually crossing at the North Pole. Here is the familiar view of the surface of the two dimensional sphere embedded in a three dimensional space is shown in the first figure. |

| How would this appear to someone trapped in the

surface, without the higher viewpoint

of the third dimension? They would map out the trajectories as

shown. We detect the positive curvature of the surface in the convergence of the paths of the travelers. Had they diverged, we would have diagnosed negative curvature. |

Can we find similar effects in spacetime? Then we would have found curvature. So what we seek is a sheet of spacetime in which we find converging or diverging curves. As we shall see, that will be easy to find. A collection of masses in free fall in a gravitational field will provide exactly the sort of curves we need.

To get us started, we will take the simplest case as far as the curvature is concerned, although the set up physically is a bit messier.

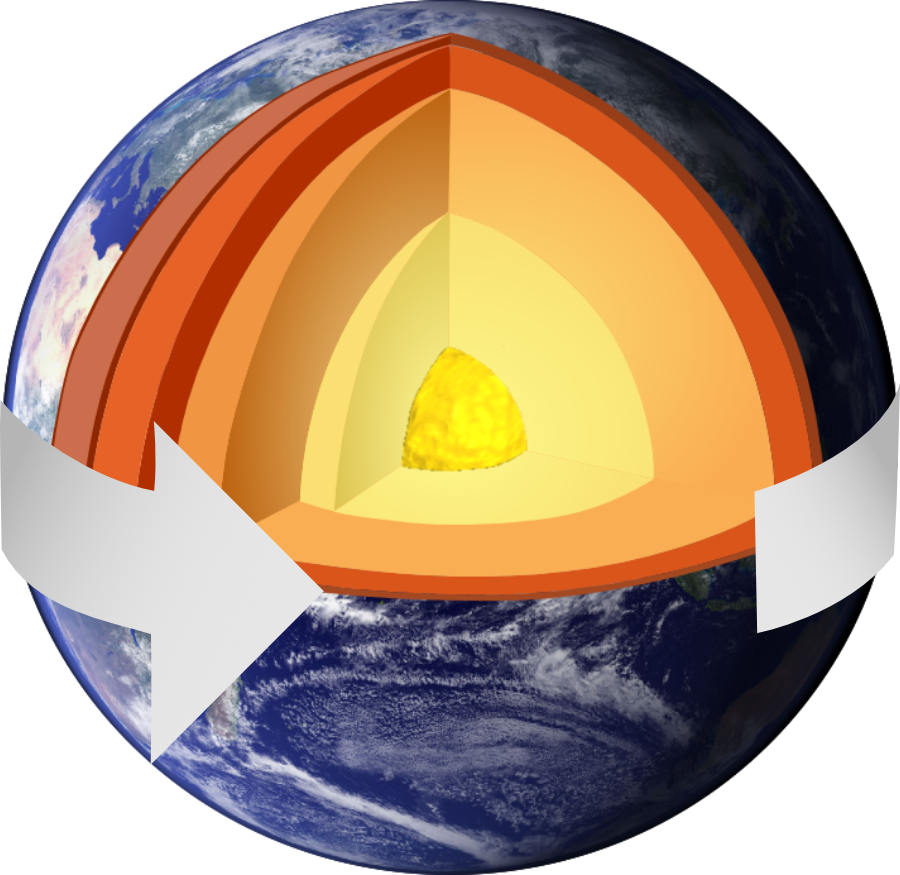

| Imagine that we drill a hole through to the center of the earth and out to the other side. It will be about 7900 miles long. We evacuate the resulting tube and cap it so that bodies dropped in the hole can fall without any air resistance at all. |

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Earth_cutaway.png |

| A small ball dropped from the surface falls to the center and arrives there in 21 minutes, ... | |||

| ... it rushes past the center towards the other side, where it arrives in another 21 minutes and momentarily stops ... | |||

| ... It then falls back towards the center and arrives there in 21 minutes ... | |||

| ... it rushes past the center and returns to its starting point, where it arrives after 21 minutes. Overall, a complete cycle is completed in 21+21+21+21 = 84 minutes. The cycle repeats indefinitely. The ball oscillates back and forth with a period of 84 minutes. |

One of the oddities of gravity is that this period of 84

minutes (= 42 minutes there + 42 minutes back) is fixed, no

matter

where the ball may first be released. Imagine, for example, that

it is released from rest halfway between the surface and center. It would

take the same 42 minutes to cross the center and come momentarily to rest

at the corresponding point on the other side of the center; and then

another 42 minutes to make the trip back to its starting point

Another property that will shortly be seen to be important is that the timing is independent of the mass of ball. A heavy ball and a light ball will both fall in the same way and oscillate in the hole with a period of 84 minutes.

| Here's an animation that shows balls starting at different places in the hole. Imagine that the balls are so small that they pass by one another without interference. (That is hard to draw, so the animation just shows them passing through each other.) |  |

||

|

|

Now let's plot the motions through time over the 42 minutes needed for a ball to fall past the center and come to rest at the other side. | ||

| This plot has now given us a spacetime diagram of the motions of the balls. It is just: |

|

If you compare this spacetime diagram to the earlier figure of the travelers on the earth's surface, you will see that they agree in the essential aspect. They both show converging trajectories, the hallmark of positive curvature. This allows us to interpret the gravitational motions in a novel way.

The temptation is to call this convergence "geodesic deviation." We need to be a little cautious here since the trajectories in the spacetime are not necessarily geodesics, that is, curves of shortest distance. They are not in Newtonian theory. In relativity, both special and general, they are timelike geodesics. That is, they are curves of greatest proper time, which is the analog of the straight lines of Euclidean geometry, the curves of shortest distance. So we can yield to the temptation and, in so doing, arrive at the essential idea of Einstein's theory.

Here's how we pass to the essential idea of Einstein's theory.

Newton's

theory: These motions are due the force of gravity deflecting

the bodies from the trajectories they want to follow into the

oscillations we see.  |

Reinterpreted

theory: the sheet of space-time displayed in the spacetime

diagram is intrinsically curved. The trajectories followed by the

bodies in free fall are simply the straightest lines of this new

curved geometry. We'll call this a sheet of space-hyphen-time to indicate that the sheet has one spatial dimension and one temporal dimension. Don't even try to imagine this as extrinsic curvature, the bending of a surface into a higher dimensioned space. That way leads to madness! Think of the curvature intrinsically, that is, as a geometrical effect arising entirely within the surface.  |

This case of free fall inside the earth turns out to be an

especially simple case as far as curvature is

concerned in two ways.

| First, the curvature of the space-time sheets explored by these falling masses proves to be constant throughout the sheet. That follows since the rate at which neighboring balls in the sheet converge is the same throughout the sheet. | This constancy is not too hard to see. If one works out the Newtonian gravitation theory, it turns out that the acceleration due to gravity of a ball in the tube grows linearly with distance from the center of the earth. That means that with each additional mile's distance, we add the same increment to the acceleration of the ball. Therefore if two balls are separated by one mile in height anywhere in the tube, their relative acceleration will be the same. Since the relative acceleration fixes the rate of convergence, that rate will be the same everywhere. Since the rate of convergence fixes the curvature, it follows that the curvature is the same everywhere. |

Second, the magnitude of the curvature does not depend on the mass or size of the earth; it depends only on the mass density of the earth. (This is not obvious. An easy calculation in Newtonian theory can show it, however.)

These last two points are important enough to be stated in a relation that is close to (but not quite) one that holds very generally:

|

Curvature of space-time sheet

within the earth

|

is proportional to

|

matter density of the earth

|

In this formula Newtonian "mass density" has been replaced by the vaguer "matter density" in anticipation of what will transpire in general relativity, where the density of matter is a more complicated quantity that embraces energy and momentum densities as well as stresses.

The analysis can be generalized. We considered just one space-time sheet, the one swept out through time by the hole we imagined drilled through the earth. Nothing in the analysis depended upon where we drilled the hole. We could have drilled many holes. Each would sweep out a different sheet in spacetime to which this analysis would apply. In general, there are three independent spatial directions we could have chosen, correspondingly to the three axes of a three dimensional space. Finding the curvature in the three resulting sheets would be enough to fix the curvature in all possible sheets generated by holes we may dig.

| We have reinterpreted gravitational accelerations as manifestations of an intrinsic curvature of spacetime. So far, we have actually posited nothing new, physically beyond "geometrizing away gravitational forces." Everything said so far could be carried through in Newton's theory of gravity without affecting any of the observationally testable predictions of the theory. We have just re-packaged an old theory in a unfamiliar wrapping. | There is one complication in this re-packaging of Newtonian gravitation theory. Free falls are not definable as curves in spacetime of greatest time elapsed, as they are in special relativity and will be in general relativity. So a more complicated construction is needed to make sense of the straightness of trajectories of free fall in Newtonian gravitation theory. Its details need not trouble us here. From this perspective, however, Newtonian theory turns out to be more complicated than general relativity! |

| One special fact about gravity makes it an especially apt redescription. There is a uniqueness in free fall trajectories that is peculiar to gravity. If we drop a one pound ball in the tube, it will take 42 minutes to pass to the other side of the earth. The same is true of a two pound ball; or a three pound ball; or a ball of any mass. They all take 42 minutes to pass to the other side of the earth. While they do it, they follow exactly the same trajectory. So if we release a one, two and three pound ball at the same moment, they will remain together as they traverse the hole to the other side. This is the uniqueness of free fall. |

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pisa_basilica_tower_c1830.jpg |

It is just the latest version of the result Galileo made famous when he wrote of dropping objects of different mass from a tower and noting that they would fall alike. |

In Newtonian theory, the result is given more complicated expression. The quantity that measures how much gravitational force will act on a body in some gravitational field is its gravitational mass. The quantity that measures how much a given body will accelerate when acted on by a force is the body's inertial mass. It is an unexplained coincidence in Newtonian theory that these two masses are equal. The result is the uniqueness of free fall.

| Let us spell this out a little more. A two pound mass feels twice the gravitational force than does a one pound mass in the same gravitational field, since it has twice the gravitational mass. |

| One might expect that, if we drop the two masses,

the two pound mass would fall faster because it is acted on by twice

the gravitational force. A second factor comes into play that erases the effect of the increase. In Newtonian gravitation theory, a body with a two pound gravitational mass will also have a two pound inertial mass. The inertial mass of the body tells us how much acceleration the body acquires when acted on by a force. (The precise relation is acceleration = force/mass.) Thus, in passing from the one pound to the two pound mass, we have doubled both the inertial and the gravitational mass. So we have doubled the gravitational force, but halved the responsiveness of the mass to the gravitational forces. The outcome is that both masses fall with exactly the same acceleration. |

If electric forces were pulling the balls through the tube, this uniqueness of fall would fail. There is no coupling of inertial mass and electric charge. So if we drop one body which carries twice the charge of a second, there is no assurance that the inertial mass is also doubled; and so no assurance that the two will fall alike.

This remarkable result of the uniqueness of free fall is what makes the reinterpretation very comfortable. We can think of the spacetime sheet as having a natural spacetime geometry revealed to us by masses. That geometry is largely independent of the test masses that fall within it. All masses--big and small--reveal the same trajectories. The masses are more like probes exploring an independently existing structure.

It is as if we can see trains moving at night or in dim light. If we didn't know how trains worked, we might be puzzled that they all follow the same paths

Based on public domain image at

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_SBahn_HackescherMarkt_east.jpg

But when the light comes, we can see that there are

railroad tracks covering the ground and that the trains

merely follow them. We can use them as probes in the dark that

reveal where the tracks lie.

Based on public domain image at

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_SBahn_HackescherMarkt_east.jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Railyard_LA_river.jpg

Finally Einstein's reinterpretation eradicates an awkwardness of Newtonian theory. That theory had to posit that increases in gravitational mass in bodies are perfectly and exactly compensated by corresponding increases in inertial mass, so that the uniqueness of free fall can be preserved. Einstein's redescription does away with that coincidence and even the very idea of distinct inertial and gravitational masses. In his theory, bodies now just have mass, or, in the light of special relativity, mass-energy. For Einstein the primitive notion is the geometrical structure of spacetime with the curved trajectories traced out by all freely falling bodies, independently of their mass.

So far, we have dealt with an especially simple case in which the curvature of the space-time sheet is everywhere the same. More generally curvature in spacetime will vary from event to event and, even at one event, it will be different according to the particular space-time sheet considered. This is simply a re-expression in curvature language of the more familiar fact that gravitation varies from place to place and acts differently in different directions.

We can explore this variability by considering masses falling under the action of gravity above the surface of the earth. (As before, we will ignore the rotation of the earth.)

To begin, consider masses 100 miles above the surface, stacked up 1 mile apart as shown and initially at rest with respect to earth.

Now let them fall freely. The masses closer to the earth will feel a slightly stronger pull of gravity, so they will fall slightly faster. It is easy to compute the effect. In the course of 18.3 seconds, the masses will fall roughly one mile. A mass that is one mile closer, however, will fall 1.6 feet more than a mass starting one mile higher.

If we plot these motions through time on a spacetime diagram, we recover a familiar figure.

This is just a space-time sheet showing diverging trajectories; that is, this particular space-time sheet has negative curvature.

We will get a different outcome if we consider masses aligned horizontally. As before they are 100 miles above the surface of the earth and spaced one mile apart, but now they are distributed horizontally.

In this case, each mass will feel the same gravitational force. However those forces will pull in a slightly different direction for each mass. The forces are all directed towards the center of the earth. If the masses start from rest and go into free fall, after 18.3 seconds they will have fallen one mile. Since they are being pulled by forces that converge to one point, the center of the earth, the masses will have converged slightly in the course of falling. It turns out that each mass will be 0.8 feet closer to its neighboring masses as a result of the motion.

These motions can be plotted on a spacetime diagram, from which we recover a familiar figure.

This is just a space-time sheet showing converging trajectories; that is, this particular spacetime sheet has positive curvature.

To sum up, we can identify three space-time sheets passing through an event 100 miles above the surface of the earth in which free fall motions are plotted. In the sheet spatially oriented in the up-down direction, we find a negative curvature. The remaining two sheets are spatially oriented east-west and north-south. In each of those we found a positive curvature.

By considering masses in free fall within a tube bored through the earth, we saw a connection between the curvature of the space-time sheet and the matter density. Since we know that matter produces gravity and that gravity is now to be represented by a curvature of spacetime, you might suppose that this is a general relation. Could the spacetime curvature just be proportional to matter density everywhere?

| ??? |

curvature of

space-time sheets |

is proportional to

|

matter

density |

??? |

That clearly doesn't work. Above the surface of the earth, there is no matter density, but there certainly is gravity and, as we have just seen, curvature of the space-time sheets as well.

So we need a weaker relationship between curvature of the space-time sheets and matter density. That relationship turns out to be easy to see if we just tabulate the cases we've seen so far. The curvature revealing deviations in the space-time sheets, as mapped out by masses in free fall, will be measured by the convergence or divergence of masses one mile apart when they fall one mile.

| Convergence (+) or Divergence (-) of bodies one mile apart in free fall for one mile. | ||

| Inside the earth | Above the earth | |

| Up-down | +0.8ft | -1.6 ft |

| East-west | +0.8ft | +0.8ft |

| North-south | +0.8ft | +0.8ft |

| Total | +2.4 ft | 0 |

The table suggests the correct result. For the case of space-time sheets above the earth where there is no matter density, the curvature revealing deviations in each is non-zero. But their sum is zero. We define the summed curvature to be the sum of the curvatures of the space-time sheets for the three different spatial directions. Then we can write the connection between curvature and matter density as:

|

Summed curvature of

space-time sheets |

is proportional to

|

matter

density |

This relation amounts to a natural relaxing of the too stringent condition that curvature must be proportional to matter density. For with the relaxed condition, we can still have curvature in the individual space-time sheets at events where the matter density vanishes. For example, we can have negative curvature in the sheets aligned with the up-down spatial direction. But to keep the summed curvature zero, we must have positive curvature in sheets aligned in the other directions.

All our considerations so far apply equally to Newton's theory of gravity (with the notion of free fall trajectory given a suitable geometric reinterpretation) as to Einstein's new theory. They have dealt only with curvature of space-time sheets, that is, in two dimensional surfaces in spacetime that are spacelike in one direction and timelike in another.

As the figure shows, the spacetime will also have space-space sheets. These are just the ordinary two dimensional slices of three dimensional space. Within the context of Newton's theory, reinterpreted as a theory of spacetime curvature, curvature does not extend to them.

That they should be treated differently makes sense in the Newtonian context. For there space and time are treated very differently.

It is quite another matter when we move to relativity theory. The core innovation of Einstein's special theory of relativity was a mixing together of space and time, manifested most vividly as the relativity of simultaneity. In a Minkowski spacetime, there are many ways to slice up the spacetime into spaces that persist through time. So, in the relativistic context, it is no longer so natural to have one rule for space-time sheets and another for space-space sheets.

Where Einstein's general theory of relativity deviates sharply from Newton's is that Einstein requires the curvature associated with gravity to extend from space-time sheets to space-space sheets as well; and for all to be governed by the same relationship. This difference can be summarized as:

|

|

|||||

|

Newton's theory of gravitation

rendered as a curved spacetime theory

|

Einstein's general theory of

relativity

|

|||||

|

Summed curvature of space-time

sheets

|

is proportional to

|

matter density

|

Summed curvature of all sheets of

spacetime, space-time and space-space

|

is proportional to

|

matter density

|

|

|

No curvature in purely spatial

space-space sheets

|

||||||

| Timelike geodesics are not well-defined. (Other geometric structures not discussed here control the trajectories of bodies in free fall.) |

Bodies in free fall follow timelike geodesics of the variably curved, metrical spacetime geometry. There are no gravitational forces. | |||||

This table summarizes the core ideas but avoids a lot of very messy technical and mathematical issues. Let us just consider Einstein's theory.

What ought to represent matter density? In Newtonian mechanics, that would just be mass density. We learned from special relativity that mass is not such a simple quantity. The real concept is mass-energy and what complicates things further is that the amount of mass-energy a body has will vary with the frame of reference. These are just the beginning of a series of complications.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Large_Stratocumulus.JPG

It turns out that an adequate representation of the matter density at an event in spacetime requires a catalog of a lot of information: energy density, momentum densities, energy fluxes and all the various forms of stress that may also be present. The synopsis of all this information in a 4x4 table is known as the stress energy tensor. The quantities just listed are usually represented by a capital T and two subscript numbers. That is, they are 16 numbers: T00, T01, T02, ... , T33. Laid out in a table, they look like this:

| T00 | T01 | T02 | T03 | mass energy density | energy flux = momentum density | |||||

| T10 | T11 | T12 | T13 | = | energy flux = momentum density |

normal pressure | shear stress | shear stress | ||

| T20 | T21 | T22 | T23 | shear stress | normal pressure | shear stress | ||||

| T30 | T31 | T32 | T33 | shear stress | shear stress | normal pressure | ||||

I've included a decoding of what each of the T00, T01, ... mean, but you should not worry too much about these details. It would take a much longer exposition that given here to make sense of it all. All you need to see is that the quantity known as the stress energy tensor is really a bag that holds a lot of information about what is present in spacetime at some point: its energy density, its momentum densities, pressures, stresses and so on.

There is a similar problem in determining precisely which quantity should represent the summed curvature. There is a single 4x4x4x4 table, known as the Riemann curvature tensor, that represents all the curvature information pertaining to the different sheets in spacetime. The entries in the table are represented by the numbers R0000, R0001, R0002, ... , R3333. Somehow we need to extract an appropriate sum of curvature quantities from it. There are several ways to do this.

Deciding which was the right way proved to be a special stumbling block for Einstein. The final answer, however, became so strongly connected with Einstein's theory that it is now named after him. It is called the Einstein tensor. As with the stress-energy tensor, the Einstein tensor can be written down as a 4x4 table of numbers computed from the numbers in the 4x4x4x4 table of the Riemann curvature tensor.

The 16 numbers that form this table are written as G00, G01, G02, ... , G33. Laid out as a table, they look like

| G00 | G01 | G02 | G03 | ||

| G10 | G11 | G12 | G13 | ||

| G20 | G21 | G22 | G23 | ||

| G30 | G31 | G32 | G33 |

The precise mathematical expression of the connection between summed spacetime curvature and matter density just sets the two tables equal to each other. It is done term by term in the tables: G00 = T00, G01 = T01, ... , G33 = T33. The resulting set of equations is one of the most famous and most important equations in physics and is known as:

Einstein's gravitational field equations |

||

| EINSTEIN TENSOR |

equals | STRESS- ENERGY TENSOR |

These are the core equations of Einstein theory and the crowning glory of Einstein's discovery. In one set of equations they embrace the entirety of gravitational phenomena as well as the geometry of space. They appear in the text books like this:

Gμν = Tμν

Gik = Tik

Gab = Tab

Gab = 8π Tab

These equations decide which spacetimes--that is, which universes--are admissible according to Einstein's theory. The admissible ones will be those spacetimes in which the spacetime curvature and matter density are related appropriately.

While this is easy to say, the mathematical difficulty of finding a spacetime that satisfies Einstein's equations is immense. Success is so hard that we usually celebrate it by naming the spacetime after the person who first shows that it satisfies the gravitational field equations.

| It turns out that there is just one example that is simple enough for us to see without any hard calculations. Consider a flat Minkowski spacetime of special relativity and imagine that it is completely empty of all matter. Since it is flat, its curvature is zero at every event; therefore its summed curvature at every event is zero; therefore the Einstein tensor is zero. Since it is empty of all matter, its stress-energy tensor is also zero everywhere. Combining, we see that Einstein's gravitational field equations are satisfied: the Einstein tensor equals the stress-energy tensor since both are zero. | "The Einstein tensor is zero." "The stress-energy tensor is zero." What can that mean when neither is a number? Each are 4x4 tables of numbers. It just means that each number in the 4x4 table is zero. That is, it means just what you thought it means. |

| Minkowski spacetime: | flat spacetime geometry | and | matter-free |

| curvature tensor is zero, so summed curvature tensor is zero, so Einstein tensor is zero. |

stress-energy tensor is zero | ||

| EINSTEIN TENSOR | equals | STRESS-ENERGY TENSOR |

Note that we cannot turn this around. If we have a spacetime in which the stress-energy tensor is zero, so that the Einstein tensor is zero, it does not now follow that the curvature is also zero. We have already seen that one can have a non zero curvature that yields a zero summed curvature.

You have now seen the basic suppositions of Einstein's theory. Our situation is rather like what happens after you have read the first few pages of Euclid's Elements of Geometry. Once you know the five postulates, there is a sense in which you know the whole geometry: you have enough information to infer all the theorems by simple logic. Of course the project of finding all those theorems is enormous. It is the same with general relativity. The basic ideas of the theory have been given to you, but finding out what the theory really says is possible is an enormous and difficult project. Only a small part of it will occupy many more chapters. We will be building entire worlds.

Copyright John D. Norton. February 2001;

January 2, 2007, February 15, August 23, October 16, 27, 2008; February

5, 2010; February 18, 2015. February 20, 22, 2017. October 10, 2018. Links

added November 18, 2019. September 28, 2020. February3, 2022. February 21, 2024.