| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

Special relativity has changed our understanding of the nature of space, time, energy and other physical quantities. There is a very widespread feeling that the advent of special relativity has somehow changed the way we look at things in a sense that goes beyond these narrow physical results. What might that sense be?

The problem in answering is that there is scarcely a viewpoint or movement in modern philosophical thought that does not claim support in one way or another from Einstein's achievement. Clearly they cannot all be right. Quite often radically opposed viewpoints claim support from Einstein's achievement. In the end it is up to you to decide, since the issue remains controversial. You should use your knowledge of Einstein's theory and the circumstances surrounding its emergence to assist you.

Deciding what this significance might be is a

philosophical problem of no small interest. It must be resolved by the standard

methods of philosophical analysis. These methods are simple to

describe and not so difficult to learn. To begin, we need to keep two

notions in mind:

| Critical analysis of the positions laid out then

merely consists in checking that each of these

elements is implemented properly. We would check that the thesis is

clearly formulated. We could check that the premises of the

arguments used are true. We would check that the steps of the

arguments are valid; that is, that they conform to the canons of

good reasoning. These requirement concerning thesis and argument are easy to state and look rather simple to satisfy. That is true as long as the problems dealt with are themselves easy. However once we start to entertain the traditionally intractable problems of philosophy, holding to them can be come quite demanding. Success at it may be a significant achievement and the best work in philosophy is distinguished by its success in holding to them in adverse circumstances. |

What is meant by "logic forces"? I just mean that

the inference from X, Y and Z to C is a valid argument, where

"argument" means what it means in any introductory logic class. If

you haven't had such a class, you should. It will help you clarify

your thinking a great deal. There you will learn than an argument is

not a shouting match. It is a sequence

of propositions. A valid argument is one in which each

proposition of the sequence is either introduced as a premise or

inferred from propositions earlier in the sequence. A valid deductive argument is one in which the truth of the premises necessitates the truth of conclusions inferred. For example: 1. All men are mortal. (Premise) 2. Socrates is a man. (Premise) 3. Socrates is mortal. (Inferred from 1.,2.) is a valid argument since, if premises 1. and 2. are true, then the conclusion 3. must also be true. A valid inductive argument is one in which the truth of the premises make the conclusion very likely to be true (or, sometimes, merely lend support to the truth of the conclusion). For example: 1. Most elephants are gray. (Premise) 2. Jumbo is an elephant. (Premise) 3. Jumbo is gray. (Inferred inductively from 1., 2.) is a valid inductive argument. |

Our goal is to take something that is puzzling, vague and elusive and make it precise and definite. If we do it right, the resolution of the puzzle should seem so straightforward that we wonder why it ever seemed otherwise.

The obvious candidate is just the basic content of the theory itself. It tells us some pretty surprising things about space and time and the matter they contain: that c is a fundamental barrier to all motions; that moving clocks slow; that simultaneity is relative; that energy and mass are equivalent; and so on. In so far as a perennial problem of philosophy has been to discern the nature of space and time, this is a reasonable answer. However it is usually thought that the advent of relativity somehow changed something fundamental, perhaps in how we see ourselves in the universe, or, more narrowly, in how we conduct our scientific investigations of that universe. Our quest is for morals of that type.

This and the next two chapters will describe some candidate morals of this broader type. I will give you my reaction to them to give you an example of how these claims may be analyzed and also to let you know what I think. Do you agree? Make up your own mind. Your decision will be reported in the assignment.

This chapter will develop skeptical morals.

Einstein has shown us that the fundamental quantities

of physics are relative. Is this not a quite general moral? Is not what

is true or false or what is right or wrong relative to the individual?

Should we not say "Everything is relative"?`

The slogan "It's all relative" or "Everything is relative"

is quite pervasive in modern culture.

In spite of the pervasive presence of these expressions, I've found it hard to locate serious scholarship that is based on them. Rather they seem to be used as catchy slogans without any serious attempt to give them a secure foundation.

In a search for serious projects based on the slogan, I ended up looking at the skeptics of ancient Greece. Their overall project was to cast doubt on the idea that we know anything at all. We should doubt everything. Here is how it appears in the work Outines of Scepticism of, Sextus Empiricus, a second century AD Greek philosopher.

As preparation for the general claim, Sextus Empiricus notes that all our judgments of characteristics of things are made in relation to something else. Sand grains, looked at closely, are rough; but a sand dune seen from a distance is smooth. He concluded (p. 34):

"... we can say what they [things] are like relatively, but we cannot say what the nature of the objects is like in itself because of the anomalies in the appearances which depend on their compositions."

This leads up to his general claim (p. 36):

"... since we have established in this way that everything is relative, it is clear that we shall not be able to say what each existing object is like in its own nature and purely, but only what it appears to be like relative to something. It follows that we must suspend judgement about the nature of objects."

Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Scepticism. eds. Julia Annas and Jonathan Barnes. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

This use of the expression "everything is relative" came nearly two thousand years prior to relativity theory in physics. There can be no suggestion that Sextus Empiricus was somehow influenced by Einstein. His words have been translated from ancient Greek and, in their English translation, have something of an Einsteinian cadence for many people. Presumably there is no such association for the expression in the original Greek.

Let us now ask whether this slogan can find support from Einstein's special theory of relativity

Here's the thesis and argument reconstructed:

Thesis: Everything is relative. There

are no absolute truths or absolutes of moral rectitude.

Argument:

1. All quantities in relativity theory have a meaning only relative to an

inertial frame or to an inertially moving observer. (Premise)

2. Relativity theory revealed that we were mistaken in our earlier belief

in absolute quantities in physics. (Premise)

3. Other notions (truth, moral rectitude) are like the quantities of

physics.

4. The lesson of relativity theory can be applied elsewhere. (1., 2., 3.,

by analogy)

5. Everything is relative. There are no absolute truths or absolutes of

moral rectitude. (From 1., 2., 3.)

Reconstructing the argument explicitly is already pretty damning. One sees that the moral is poorly drawn. Although it is obvious, let us spell out why.

First, the argument

is invalid. It seeks to use an argument by analogy. (This is like

that in some aspects; therefore this is like that in other aspects.)

The analogy fails. That certain quantities in relativity theory are

relative to the observer or, better said, state of motion of the observer,

has no real bearing on whether there is one

absolute standard for truth or for what is good or morally right. The same

word--relativism--is used in all cases, but the similarity of meaning is

so superficial as not to allow success in one domain to carry to another.

Second, the first premise is false. It is not true in relativity theory that "everything is relative." Only certain quantities are, albeit more than in classical physics. Some quantities are not relative. The simplest examples are the so-called "rest" quantities: rest mass, rest length etc. These are by definition the masses and lengths measured by a co-moving observer. They are characteristic properties of bodies and are of fundamental physical importance; (obviously) all observers must agree on their values. They are an absolute.

| It is something of an accident of history to do with Einstein's way of thinking about relativity theory that we stress the "relative" aspect of the theory. In the more mathematical approach to the theory, what draws most attention is what is not relative, the so-called "invariants." So early in the history Einstein agreed with the great mathematician Felix Klein that a better name for the theory would have been "theory of invariants." |  |

|

Working in that mathematical tradition, Hermann

Minkowski, who introduced the notion of spacetime, wrote in his 1908

lecture "Space and Time": "...the word[s] relativity-postulate for the requirement of an invariance with the group Gc seem to me feeble. Since the postulate comes to mean that only the four-dimensional world in space and time is given by phenomena, but that the projection in space and in time may still be undertaken with a certain degree of freedom, I prefer to call it the postulate of the absolute world (or briefly the world-postulate)." |

Had history paid more attention to Minkowski's advocacy of the absolute world, might I now be lamenting the fallacy of inferring that "everything is absolute" from Einstein's theory?!

Here are the defects of the argument, displayed in compact form:

Thesis: Everything is relative. There

are no absolute truths or absolutes of moral rectitude.

Argument:

1. All quantities in

relativity theory have a meaning only relative to an inertial frame or

to an inertially moving observer. (Premise)

False premise: only some quantities in

relativity theory have a relative meaning.

2. Relativity theory revealed that we were mistaken in our earlier belief

in absolute quantities in physics. (Premise)

3. Other notions (truth, moral rightness) are like the quantities of

physics.

4. The lesson of relativity

theory can be applied elsewhere. There are no absolute truths or

absolutes of moral rectitude.(1., 2., 3., by analogy)

Fallacy: the analogy is too weak to

support the inference.

5. Everything is relative.

There are no absolute truths or absolutes of moral rectitude.(From 1.,

2., 3.)

Conclusion improperly drawn.

Relativity shows us that we cannot expect our common sense ideas about the physical world to be reliable.

Here is a reconstruction in terms of thesis and argument.

Thesis: Common sense is an unreliable

guide to truth.

Argument:

1. If common sense is a reliable guide to truth, then it will not assure

us of falsehoods. (Premise)

2. Common sense assures us that well-made rods and clocks are unaffected

by their motion. (Premise)

3. Relativity tells us that well-made rods and clocks shrink and slow when

they are moving. (Premise)

4. Common sense assures us of falsehoods. (From 2., 3.)

5. Common sense is not a reliable guide to the truth. (From 1., 4.)

On its face, this is acceptable. This claim is clear enough. The argument employs true premises and valid inferences. Informally, we had commonsense ideas about rods, clocks, simultaneity and more. We believed them because they seemed, well, commonsensical. Relativity showed that they were incorrect. Therefore commonsense ideas are untrustworthy, or at least on some occasions.

While the thesis and argument are acceptable, the view is oversimplified and the oversimplification is misleading.

It suggests that we needed relativity theory to tell us that common sense is unreliable. Anyone who has ever attended to developments in science will find numerous examples of science revealing the fragility of commonsense ideas. Copernicus did just that to our commonsense idea that we are at rest; he showed that we hurl through space at great speed in space, spinning all the while.

More seriously, the implicit assumption is that science and common sense are opposed. That is, they are two distinct ways that we know about the world. They are not distinct. There is an important connection between scientific breakthroughs and common sense.

Here's a list of things that we know through commonsense:

The sky

cannot fall down.

Cows cannot jump over the moon.

The earth is spherical.

People venturing to the other side will not fall off.

The earth spins on its axis and orbits the sun.

Matter is made of atoms too small to see.

Nothing goes faster than light.

The items of the list become successively more sophisticated. Indeed inspecting them reveals that each item of today's commonsense is a major result of yesterday's science.

What this suggests is that there is no independent notion of a common sense idea that somehow sits outside what we know through systematic investigations. Rather commonsense is a by-product of those investigation. The broad acceptance of common sense ideas about our physical world is merely the final stage of absorption of the results of scientific investigation. That is why today's common sense is yesterday's scientific breakthrough.

From this we can infer a more subtle moral: there is a kind of reliability in common sense ideas since they are ultimately, though indirectly, grounded in something more solid. Rather than needing a blanket skepticism about common sense ideas, the real thing to guard against is common sense that does not keep pace with newer investigations.

This file comes from Wellcome Images, a

website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based

in the United Kingdom.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:An_allegory_of_malaria._Reproduction_of_an_engraving_after_M_Wellcome_V0010519.jpg

For example, it still seems to be a part of common sense that "airs" can be good for you. Don't we know of the benefits of clear mountain air? Similarly the wrong "airs" were thought to be unhealthy. The disease of malaria--literally "bad air" mal aria--was thought to be caused by them. Of course we now know that malaria is really caused by infection from mosquito borne parasites with the mosquitoes coming from swamps that might also emit bad smells. So the idea of avoiding bad smelling places to avoid the disease was right, but only indirectly.

Now let us return to the original argument to see how it should be adjusted. What we now see is that the first premise is misleading us. It says

1. If common sense is a reliable guide to truth, then it will not assure us of falsehoods. (Premise)

The ambiguity lies in "reliable." If we take "reliable" to mean "infallible" then the argument goes through.

Thesis: Common sense is not an infallible

guide to truth.

Argument:

1. If common sense is an infallible guide to truth, then

it will not assure us of falsehoods. (Premise)

2. Common sense assures us that well-made rods and clocks are unaffected

by their motion. (Premise)

3. Relativity tells us that well-made rods and clocks shrink and slow when

they are moving. (Premise)

4. Common sense assures us of falsehoods. (From 2., 3.)

5. Common sense is not an infallible guide to the truth.

(From 1., 4.)

This is what the argument really establishes. Expressed this way, we see that the original presentation of the argument led us to accept an unreasonably high standard of reliability. We would likely be quite happy to require only "generally reliable, but occasionally in error." With that more modest reading of "reliable," the argument no longer gives us such a strongly skeptical conclusion.

With the weaker sense of "reliable," the first premise becomes:

1. If common sense is a guide to truth that is generally

reliable, but occasionally in error, then it will not assure us

of falsehoods. (Premise)

False premise.

The premise is false since under the weaker sense of reliability, common sense is permitted an occasional error. We can no longer proceed to the skeptical conclusion of 5.

Relativity shows us that even the best of our

theories--classical mechanics--are unreliable. Why should we believe any

of the theories of modern science? Should we not expect the Einsteins of

tomorrow to overturn them all?

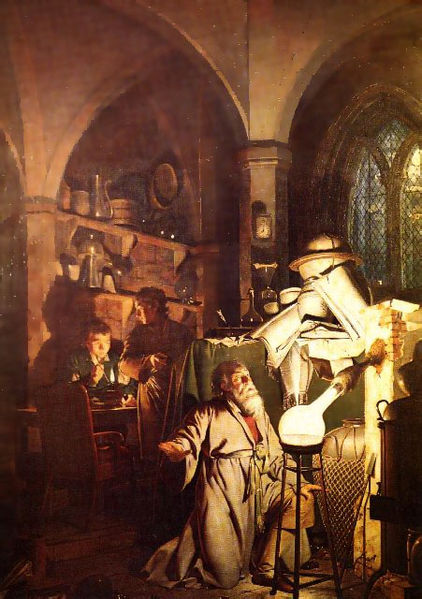

Alchemist searching for the philosopher's

stone that will convert base metals into gold.

It is a common recreation in history of science to find prominent figures who proclaim with great assurance that we have found the final truth in some area. Larry Laudan's "A Confutation of Convergent Realism," is a classical presentation of the concern. He argues that the past success of a science is no assurance that that the entities they posit are real. Here is how he uses the historical example of nineteenth century ether theories.

"It would be difficult to find a family of theories in this period which were as successful as aether theories; compared to them, 19th century atomism (for instance), a genuinely referring theory (on realist accounts), was a dismal failure. Indeed, on any account of empirical success which I can conceive of, non-referring 19th-century aether theories were more successful than contemporary, referring atomic theories. In this connection, it is worth recalling the remark of the great theoretical physicist, J. C. Maxwell, to the effect that the aether was better confirmed than any other theoretical entity in natural philosophy!"

p. 27 Larry Laudan, "A Confutation of Convergent Realism," Philosophy of Science, 48, (Mar., 1981), pp. 19-49.

Laudan's concern here is

specifically with the entities posited by the theory. He sought to impugn

the idea that terms like "aether" are "referentially successful" or

"genuinely refer." This is a careful philosopher's

formulation of one version of the skepticism that just asserts

that the aether is not real. The idea is that terms like "the Empire State

Building" genuinely refer, since they identify a real building in New

York. However "Oz," as in Baum's Wonderful Wizard of Oz, do not

refer, since there is no real place "Oz."

Here is a reconstruction of the thesis and argument:

Thesis: All present scientific theories

are false.

Argument:

1. Relativity theory showed that classical Newtonian physics, an

apparently secure theory, was false. (Premise)

2. This refutation is common: many apparently secure theories have

subsequently been overturned by later theories. (Premise)

3. We should expect this pattern to continue, if we persist in seeking new

theories. (Premise)

4. Our best scientific theories will eventually be overturned by new

theories, if we persist in seeking new theories. (From 1., 2., 3.)

5. All present scientific theories are false. (From 4.)

The thesis is clear. The argument is also clear.

Relativity is just the latest of many

instances of new science overturning old theories we thought secure. So we

should expect our latest theories will eventually also be overturned, so

don't believe them.

In my view this is a lamentable argument, defective

because it rests on false premises. Both 1.

and 2. are false. Relativity theory did not wipe away all the physics that

went before. The bulk of that physics stays intact. Classical physics only

needs relativistic corrections when we deal with velocities close to the

speed of light. In virtually all applications, from designing bridges to

launching Apollo astronauts, classical physics suffices. Premise 2. fails

in the same way for other sciences.

The real pattern is that, once a science reaches some level of maturity, it becomes a fixture in the domains in which it was developed. The much publicized revolutions that eventually do arise supply adjustments outside of those domains. Here are some examples:

| Science | Maturity achieved | Where it eventually fails |

| Geometry | Ancient Greece, Euclid 3rd century BC | On cosmic scales |

| Solar system astronomy | Heliocentrism, Copernicus, Kepler, 16th and 17th century | Very precise measurements correct their predictions but leave the heliocentric layout intact. |

| Dynamics | Newtonian mechanics, 17th century | Domains of very fast (special relativity) very heavy (general relativity) very large (relativistic cosmology) very small (quantum theory) |

There is a much more benign moral in all this: do not trust theories in domains remote from those in which they were devised. The persistence of the skeptical argument is a puzzle to me. It simply rests on defective history of science, yet it remains popular among many historians of science who should know better.

The founder of positivism, Auguste Comte, expressed essentially this view in his 1830 Cours de Philosophie Positiv. His observation appears in a remarkable passage that began with echoes of the slogan "Everything is relative."

"I merely desire to keep in view that all our positive knowledge is relative; and, in my dread of our resting in notions of any thing absolute, I would venture to say that I can conceive of such a thing as even our theory of gravitation being hereafter superseded."

Whereas he felt secure in his reservations about absolutes, he conceded that he found it hard to conceive how Newton's theory of gravity could ever fail.

"I do not think it probable; and the fact will ever remain that it answers completely to our present needs. It sustains us, up to the last point of precision that we can attain."

He allowed the possibility of a superseding theory of gravity. Even if we found such a thing, he was still confident that the present theory would continue to serve us well.

"If a future generation should reach a greater [sic theory?], and feel, in consequence, a need to construct a new law of gravitation, it will be as true as it now is that the Newtonian theory is, in the midst of inevitable variations, stable enough to give steadiness and confidence to our understandings."

Quotes from p. 184 in the Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte. Freely translated and condensed [??!] by Harriet Martineau. Vol 1. London: John Chapman, 1853.

Here is how the argument looks if we replace the false premises with true premises:

Thesis:

All present scientific theories are false.

Thesis: All present theories should not be trusted in

domains remote from those in which they were devised.

Argument:

1. Relativity theory showed

that classical Newtonian physics, an apparently secure theory, was

false. (Premise)

1. Relativity theory showed that classical Newtonian physics, an

apparently secure theory, was false in a domain remote from the one in

which it was devised. (Premise)

2. This refutation is common:

many apparently secure theories have subsequently been overturned by

later theories. (Premise)

2. This correction is common: many apparently secure theories have

subsequently been shown to fail in domains remote from the ones in which

they were devised. (Premise)

3. We should expect this pattern to continue, if we persist in seeking new

theories. (Premise)

4. Our best scientific theories will eventually be overturned

corrected by new theories, if we persist in seeking new theories. (From

1., 2., 3.)

5. All present scientific

theories are false. (From 4.)

5. All present theories should not be trusted in domains remote

from those in which they were devised.

In the two chapters following, we will see more candidate

morals described and analyzed. The morals will not be displayed formally

in terms of thesis and argument, as was done above. You should, however,

remember that they are all to be held to the same standards of clarity of

expression and cogency of argument. If thinking about them becomes

troublesome, you should revert to the standard

philosopher's questions:

What is the thesis? What is the argument?

Copyright John D. Norton. February 2001;

October 2002; July 2006; February 2, 13, September, 23, 2008; February

1, 2010; February 10, 2013; February 4, 2015. February 6, 2016. August

13, 2024.