Keith's Consciousness Page

Consciousness -- a few random thoughts.

Creativity is a subconscious period of increased memory association.

A song incessantly "running through your head" is attempting to

correlate/associate/memorize itself. The cure is to hear it again "for real," to

get enough input to lay down a good memory track.

"When all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail."

Maybe Spiro Agnew was right. Maybe rock music really does rot

the mind. Or, more precisely, music with an incessant rapid rhythm, as well as the rapid

cognitive changes of modern-style television, "entrain" the mind into faster

cycles of thinking -- just as with "music you can't get out of your head." This

may be great for improving reaction times, but may end up with a kind of societal

attention-deficit disorder, where none of us can focus our minds on a problem for more

than three seconds.

--Keith Conover (a few random thoughts from my past that led me

to this point).

One of my major academic interests lies pretty much outside of emergency medicine. It's

the neurobiological nature of consciousness. At this point I'm mostly just trying to keep

up with what's going on in the field. But once I pay off my medical school loans, and can

cut back on the number of hours I work in the ED, I hope to be able to devote a lot of

time to the subject. I don't plan to do any research affiliated with a univerisity or

anything like that -- I'm unwilling to fritter away time with paperwork and grant

proposals and tenure "publish-or-perish" battles. But I should be able to devote

time and brainpower to the topic on my own, and who knows, maybe I'll add something to the

knowledge stores of humankind. Here is a quick summary of some of my thoughts

related to recent debates on the topic.

At this point, consider these just ramblings -- but maybe with a few interesting ideas.

I'll be fleshing this out over the next year or so into a short but coherent overview of a

unified theory of consciousness.

A unified theory of consciousness. What a difficult phrase. To define a theory

of consciousness, we must delve deeply into the question of what a theory is --

fascinating, and I'd love to bring out some Karl Popper and other quotations and discuss

the issue, but not here.

A simple approach to consciousness is as follows:

A theory of consciousness is adequate if it "explains" things in terms

acceptable to a six-year-old. (This is a shorthand way of getting around the theory of

theories.) It's an entirely empirical test -- go out and find some six-year-olds and see

if they think it's a good explanation. And remember, six year old kids don't have a long

attention span, so it better be short.

Here is a start of my list of all the things a theory of consciousness must

"explain" (remember, in six-year-old terms):

- Why do we (and other animals) have to sleep?

- Why are we sometimes absent-minded? [The theory must explain why, when I just went down

into the basement to get something, I ended up doing several things and returned upstairs

without the object for which I originally set out.]

- Why do we have "Freudian slips"?

- Why do we sometimes things we don't want to do? [Don't you dare criticize the

wording unless you're a six-year-old! Any six year old will understand what this means.]

- Why do I turn on the bathroom light when it's already on? [see below]

- Why can't I see that I have a blind spot?

- Why, when I was carrying a book and a hat that I'd picked up, did I absent-mindedly put

the book where I'd planned to put the hat?

OK, here's the start on the theory:

- Consciousness

- Thesis: Consciousness is a System-Level Term

- When we speak of consciousness, we speak of whole systems -- whole beings are conscious.

Ears and eyes are not conscious, the pineal or amygdala are not conscious; human beings

are conscious.

- Consciousness is a high-level function, which subsumes many lower-level functions:

reflexes, habits and other forms of programmed response.

- Therefore, speaking about a single function of one's brain as "consciousness"

is not meaningful. Let us therefore speak of "awareness" when we are referring

to recognition of an action by a higher function of the brain that can communicate this

awareness to outside observers. "Awareness" entails much less connotative

baggage than "consciousness."

- We can become aware of some sensations and then take action on them. We can take action

on some sensations and then, after the fact, become aware that we have taken action. This

latter is possible only if the action is

- an involuntary reflex, or

- a "preprogrammed action" of some sort, such as a habit we have developed from

repetition (practice), or something that for which we have prepared (e.g., "press the

button as soon as you see the red dot")

- Consciousness is fuzzy.

- Some things are very conscious, some things are unconscious, but most things are

somewhere in-between. (Were you really conscious of that mosquito you just

slapped?)

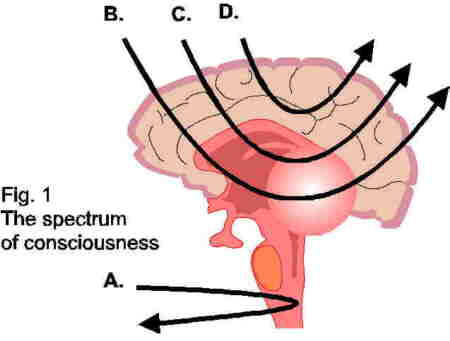

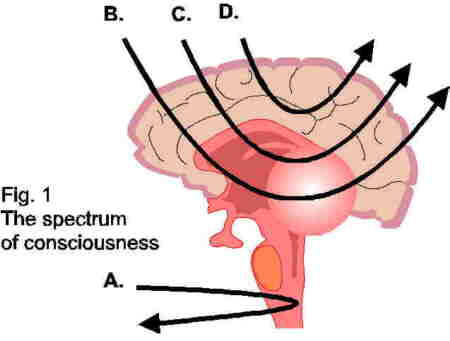

- Reflexes (Fig. 1, A.) are unconscious. Pulling a hand away from a hot

stove is the classic example; deep tendon reflexes are an even more primitive and

less-conscious (more unconscious?) example.

- We take some actions only after due cogitation (Fig. 1, B.). These are conscious

actions. Deciding to write this essay was, for me, such an action.

- Some actions we take based on preprogrammed routines (Habits; Fig. 1, D.)

Turning on the bathroom light switch is such an example (see below).

- Some actions we take based mostly on preprogrammed routines but with some (greater or

lesser) modification by cogitation (Semi-conscious actions; Fig. 1, C.) An example

is answering the telephone when distracted by writing an essay such as this (Did I really

have to think before I picked up the receiver and said "Hello?")

- So, not only are their multiple drafts of input to awareness, but some

"drafts" are louder than others.

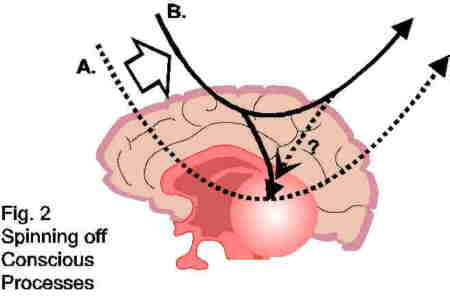

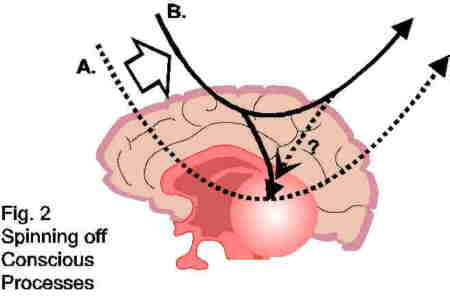

- Consciousness can "spin off" processes.

- We can then trigger the "spun off" processes without directing every detail.

We call these "habits." Due to severe thunderstorms, the power in our house was

off for about 24 hours. Every time I went into the bathroom my hand automatically turned

on the light-switch even though I knew that the power was off. Why? Because I

"triggered" my "going into the bathroom" routine, which included

turning on the light. Figure 2 shows my "entering the bathroom" habit being spun

off (changing from a conscious action at A. to an unconscious habit at B.)

- Notification that a habit has been triggered may occur after the fact.

- Processes can be either sensorimotor or just motor. "Press the button when you see

a red dot" is sensorimotor. Playing a low B-flat on my French horn is an entirely

motor "habit." Though of course some sensory feedback is necessary for me to

keep the note steady.

- One may choose to believe, as does Nicholas Humphrey in A History of the Mind, that

motor nerves include sensory feedback fibers (shown as ? in Fig. 2) and that this

is truly what is responsible for the evolution of consciousness.

- Spun-off processes can be perfected by practice. That's why when I went into the

bathroom, even though it was dark, I was able to (uselessly) hit the light switch every

time.

- Consciousness can (?) bring back "spun off" processes, or at least control

them. By the time the lights came back on 36 hours later, I had learned to enter the

bathroom without turning the light on, and had to "relearn" my "going into

the bathroom" routine.

- Consciousness is narrower than we think.

- Our vision gives us the illusion that we can see everything in our visual field clearly.

When in reality all we can see clearly is a tiny circle corresponding to the fovea of our

retina.

- Similarly, we have the illusion that we are conscious of much more than we are -- our

consciousness has a very limited grasp.

- Consciousness is a Many-Braided Stream

- Individual streamlets may take courses apart, then rush together forming a small

maelstrom, as when we make a "Freudian slip," or when our tongues become tied

and we come out with a garbled sound that is half one word and half another.

- Here is an example: I was typing something on my computer. I had thought

"just as with" and was in the process of typing this on the screen, while in the

background the radio news was saying "just after the evening news." I

typed "just after. . . " Here the input and output got shortcircuited and some

of the input went into the output.

Thanks to Daniel Dennett and Marcel Kinsbourne for their article Time and

the observer: The where and when of consciousness in the brain [Behavioral

and Brain Sciences (1992) 15, 183-247] for stimulating me to write much

of this down.

Back to Keith's Home Page

Back to Keith's Home Page