Writing About Gore

Vidal: 1951-Present

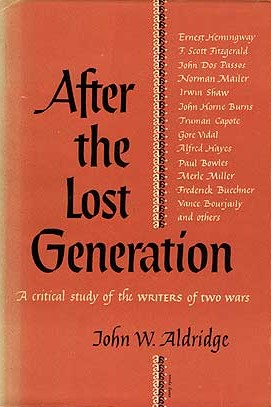

After the Lost Generation (1951)

After the Lost Generation (1951)

By John W. Aldridge

"One cannot speak of fiction without sooner or later speaking of values,"

writes John W. Aldridge, the noted literary critic, in his introduction to

After the Lost Generation: A critical study of the writers of two

wars. His book, seminal in its time, now feels rather dated because

of what Aldridge means by this assertion. And while he devotes only 14

pages to Vidal, his book offers the first critical evaluation of Vidal's

work, thus giving it a special place in Vidaliana.

Aldridge argues that the insistence of certain writers in exploring

homosexuality represents an immaturity and lack of values in their work.

That's not exactly a good place from which to evaluate Vidal's writing -

nor any writing, for that matter, if the critic's obvious homophobia so

colors his insight. In fact, Aldridge initially liked Vidal's first two

novels, Williwaw and In a Yellow Wood, when he wrote

about them contemporary to their publications. A few years later, in

After the Lost Generation - and after the appearance of The

City and the Pillar, in which Vidal essentially outed himself -

Aldridge's opinion of Vidal mysteriously changed.

In a five-page portion of his book, Aldridge suggests that

homosexuality may occur in so many novels of his time because it is "one

of the last remaining tragic types. His dilemma, like that of the Negro

and the Jew, provided a conflict which is easily presentable in fiction

and which can be made to symbolize the larger conflicts of modern man." Of

course, it never occurred to him that these novelists were simply writing

passionately about their own experience from a point of view couldn't

understand - or if it did, then the times forbade him to suggest it (or

tolerate it). He also says that "the homosexual experience is one of a

special kind, it can develop only in one direction, and it can never take

the place of the whole range of human experience which the writer must

know intimately if he is to be great."

Aldridge's displeasure with Vidal's writing seems to begin with his

second novel, In a Yellow Wood, the first with homosexual

characters. Naturally, he disliked (and misread) The City and the

Pillar, finally stating, "If Vidal showed signs in his previous work

of a weakening of his technical and dramatic power, he here shows the far

more disturbing signs of a spreading aridity of the soul." He called the

novel "purely a social document that was read because it had all the

qualities of lurid journalism and not because it showed the craft and

insight of an artist."

Aldridge concludes, at last, that "as [Vidal's characters] search for a

center of life, so he searches for a center of art." In order for Vidal's

work to achieve its goal, he argues, Vidal must discover "a value and a

morality for them and for himself."

Gore Vidal (1968)

By Ray Lewis White

Thorough, thoughtful and edifying, Professor White's critical study is the

first book-length treatment of Vidal's work. In his introduction, the

author confesses that such a historic literary undertaking "involves at

once a special pleasure and a special responsibility." His book moves in

an orderly fashion through Vidal's canon of the time, stopping with

Washington, D.C., just before Myra Breckinridge and its

manifestation of a startling new direction in Vidal's literature and

reputation.

"Gore Vidal has deserved a better hearing from literary critics than he

has received," White asserts, just before discussing Aldridge's reception

of Vidal a decade earlier. White, clearly an admirer of Vidal's writing

and point of view, discerns a range of Vidalian voices: the "literary

prince" of his prolific youth; the tradesman, who wrote for television and

magazines to support himself when his novels didn't sell; the voice that

expresses a "reasonable respect for homosexuality," and that makes the

point that "there should be no point, no pointed finger, and no

fascination at all"; and finally, "the voice of involvement to his age,"

that of a writer "involved in shaping his nation." White concludes: "Were

the author and his ideas more deeply valued in the United States, that

country would not need so desperately to hear his voices."

Interestingly, despite White's plea for society to accept homosexuality as

a matter of course, neither his chapter on Vidal's life, nor his two-page,

year-by-year account of the highlights of that life, make mention of

Howard Austen, who had been Vidal's companion since the early 1950s.

Fifteen years later, in his own Gore Vidal, Robert F. Kiernan

would discreetly correct the record.

The Apostate Angel: A Critical Study of Gore Vidal

(1974)

By Bernard F. Dick

In his smart - and smartly written - examination of Vidal's work,

Professor Dick eschews Vidalian biography in the early pages and replaces

it with some brief autobiography: He began reading Vidal while in college

in the mid-1950s, when "most college students who were eager to know what

was happening in contemporary literature pursued their interests without a

mentor." He became hooked on Vidal, and the introduction of his book

asserts: "All one can ask of a writer like Vidal is that he produce

something of value in each field he enters. I believe he has."

So the stage is set for a generous and experienced reading of Vidal's work

through Burr, a good stopping point. Dick gives his chapters

amusing titles, like "A Portrait of the Artist as G.I. Joe," "Huck Honey

on the Potomac," "Manchild in the Media," "The Hieroglyphs of Time" and

"Myra of the Movies; Or, the Magnificent Androgyne." Unique among studies

of Vidal's work, he addresses the juvenilia: poems and short stories

published when Vidal was a teen-ager, before he graduated from high school

and entered the Army. He even reprints three poems, using this passage of

his book to recount some brief biography, but always focusing on the

writing rather than the life.

So the stage is set for a generous and experienced reading of Vidal's work

through Burr, a good stopping point. Dick gives his chapters

amusing titles, like "A Portrait of the Artist as G.I. Joe," "Huck Honey

on the Potomac," "Manchild in the Media," "The Hieroglyphs of Time" and

"Myra of the Movies; Or, the Magnificent Androgyne." Unique among studies

of Vidal's work, he addresses the juvenilia: poems and short stories

published when Vidal was a teen-ager, before he graduated from high school

and entered the Army. He even reprints three poems, using this passage of

his book to recount some brief biography, but always focusing on the

writing rather than the life.

Among his astute and fluid readings of the work, Dick is not above the

occasional anecdote. "As a private person," he writes, "Vidal despises the

curious. He has been know to seat inquisitorial interviewers in a draft

and to accompany journalists seeking definitive proof of his sex life to a

bar where he would promptly leave them in their cups and stroll off with a

hooker." The tone of Dick's prose often adopts a demi-style similar to the

tone of the book he's discussing. Finally, his take on Vidal is just

right. "Vidal's allegiance to a literary past that exists, if anywhere, in

the English curriculum of the university, has seriously handicapped him,"

Dick concludes with critical admiration. "His vast reading, which must

surpass that of any of his American contemporaries, has made his standards

rigidly classical. . .Good writing is hard, gemlike prose that softens and

grows full when it becomes confessional."

Gore & Myra: A Book for Vidalophiles (1974)

By John Mitzel with Steven Abbott

Mitzel offers 35 pages of his "notes on Myra B." in this quirky little

book's predominant chapter, Patriarchy vs. "Pornography." The

notes position the indomitable (to say the least!) Myra as a Nietzchian

übermensch who "has power as her goal and lets nothing get in her

way. . . She's the Queen of Tomorrow, who'll pull a knife on you out from

under her Priscilla of Boston gown."

Camp aside, Mitzel's musings give a breezy reading to Myra through the

perspectives of feminism, sexual politics and emerging queer theory. No

section of his rapid-fire notes is longer than a page, and most are just a

paragraph or two, with the sections separate by asterisks. It ends with a

two-page coda, "Myra and Judy: A Terminal Thought," in which Mitzel uses

Judy Garland, Dorothy Gale and The Wizard of Oz to allow Judy to

teach Myra some lessons, and vice versa.

Camp aside, Mitzel's musings give a breezy reading to Myra through the

perspectives of feminism, sexual politics and emerging queer theory. No

section of his rapid-fire notes is longer than a page, and most are just a

paragraph or two, with the sections separate by asterisks. It ends with a

two-page coda, "Myra and Judy: A Terminal Thought," in which Mitzel uses

Judy Garland, Dorothy Gale and The Wizard of Oz to allow Judy to

teach Myra some lessons, and vice versa.

Next in the book comes "Three Carols for Myra Breckinridge," which are

poems penned by John Wieners, followed by Don Meuse's black-and-white

drawing of Vidal, and finally, a 40-page interview with Vidal, conducted

by Mitzel and Abbott, and originally printed in the magazine Fag

Rag. Much of the interview, which took place in Boston in November

1973, concerns sex and sexuality, although of course, politics, history,

culture and a little literature make an appearance. During the interview,

Vidal even compliments a reading of Myra Breckinridge that

appeared in Fag Rag without realizing that Mitzel wrote it.

Gore Vidal: A Primary and Secondary Bibliography

(1978)

By Robert J. Stanton

This hard-to-find resource is the first book-length bibliography of

Vidal's canon (a second one, by a different author, was published in

2007). Stanton provides detailed information on all of Vidal's book in

English and in translation through 1978, along with myriad citations of

major magazine and newspaper articles by and about Vidal. His 13-page

introduction walks through Vidal's novels and plays, offering some

analysis and critique.

Two years later, Stanton served as co-editor (with Vidal) of Views

from a Window: Conversations with Gore Vidal, an intriguing book that

brings together scores of interviews that Vidal gave to a wide range of

publications. Stanton blends the comments from various interviews and

arranges them by subject matter. The dust jacket of that book promises a

forthcoming critical study by Stanton of Vidal's work. However, no such

ever book materialized.

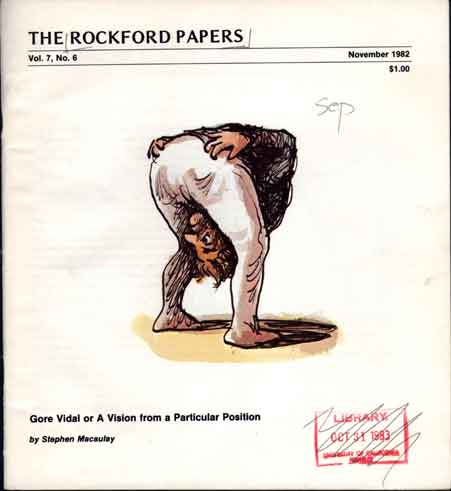

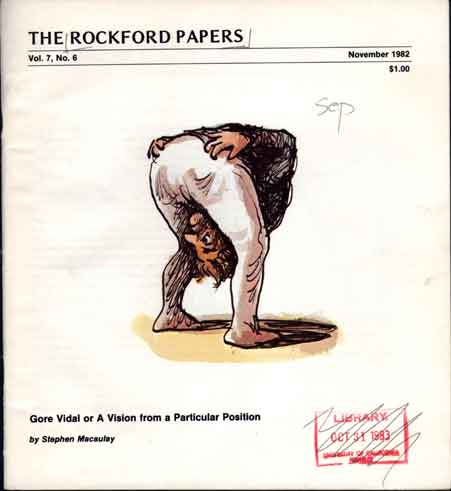

Gore Vidal or a Vision from a Particular Position

(1982)

By Stephen Macaulay

Not everyone who has published on Vidal appreciates his work. This little

anti-Vidalian tract was issued in November 1982 as Vol. 7, No. 6 of

The Rockford Papers, a series of monographs from the

ultra-conservative Rockford Institute of Rockford, Ill. In his 32-page

essay, Macaulay dissects and decimates Vidal's liberal agenda by

pretending to evaluate and criticize his fiction. The brief introduction,

by editor Leopold Tyrmand, says that Vidal's work "has a peculiar and

repelling shallowness. . .that he is skilled at passing off as

meaningfulness," and the first three pages of Macaulay's essay offer a

smug "allusive" biography of Vidal's early life, referring to him only as

"Eugene," his middle name. Then Macaulay launches into the work itself,

asserting that Vidal "thinks he is the only one left among the Barbarian

Americans who still reads anything of a more taxing nature than TV

Guide."

by editor Leopold Tyrmand, says that Vidal's work "has a peculiar and

repelling shallowness. . .that he is skilled at passing off as

meaningfulness," and the first three pages of Macaulay's essay offer a

smug "allusive" biography of Vidal's early life, referring to him only as

"Eugene," his middle name. Then Macaulay launches into the work itself,

asserting that Vidal "thinks he is the only one left among the Barbarian

Americans who still reads anything of a more taxing nature than TV

Guide."

Typical of a reactionary conservative, Macaulay rails against Vidal for

railing against society. He accuses "Vidal and his partisans" of

constructing a sinister syllogism: "These novels are disturbing;

literature is disturbing; therefore, these novels are literature." Then,

echoing Aldridge 30 years before him, he asserts "that affirmation of

rudimentary humanness is also a part of the definition. [Vidal] chooses

to affirm venom and vice and what others may call filth - he sees them all

as the core of humanity. He consequently creates a world so that he can

destroy everyone in it. It all ends in the terminal negation: evil is

proclaimed as virtue and worshipped through ultimate debasement."

This, of course, is not what Vidal does as he explores the ways in which

people of power behave and the consequences of their behavior on society.

But Macaulay, again like Aldridge, is clearly more disturbed by Vidal's

politics than his literature, even if he refuses to admit it.

Gore Vidal (1983)

By Robert F. Kiernan

A professor at Manhattan College, Kiernan continued the work done by White

(1968) and Dick (1974) in their critical studies of Vidal. This book gets

as far as Creation, and Kiernan's opening year-by-year chronology

of Vidal's life notes that Vidal was, in 1981, on the verge of announcing

his candidacy for the U.S. Senate in California. Kiernan's entry for 1951

reads: "Lectures widely. Completes The Judgment of Paris. Begins

to live with Howard Austen." This is something that White could not bring

himself to mention in the more conservative literary circle of the 1960s.

Kiernan's study adds nothing monumentally new to the literature of

interpreting Vidal, whom he affectionately calls a "patrician hauteur."

His book opens with a critical biography, then goes on to discuss the

novels in groups, such as: the early successes (Williwaw and

The City and the Pillar), the ancient world, the American

trilogy, the Breckinridge novels, the essays, and the minor works (smaller

early novels, including Messiah, the Edgar Box mysteries and the

short story collection A Thirsty Evil).

Kiernan begins by discussing the several Vidalian manners: patrician

("cool, elegant, and somewhat haughty"); outré, ("witty, risqué,

obstreperous"); and intellectual ("epigrammatic, iconoclastic, and

cheerless"). "These manners and others that are shadings or combinations

of them are carried off with aplomb by Vidal both in his life and in his

writing," Kiernan writes. "But they are indubitably manners,

stylizations of the self that conceal as much of the man as they reveal."

The notion of Vidal's many voices winnows through Kiernan's book, until

his summation asserts, "Because Vidal is a writer with many voices, his

career seems a history of elaborate feints and passes." He calls Vidal a

farceur for whom "insouciance and insolence regularly join forces

in his rhetoric." But he's careful to point out that noting Vidal's

limitations "does not constitute an attack." He concludes: "The great

charm of Vidal's writing is its auctorial audacity. . .The Vidalian

persona, con brio, is the ultimate achievement of Vidal's art."

Gore Vidal: Writer Against the Grain (1992)

Edited by Jay Parini

Jay Parini's friendship with Vidal began in Italy in the 1980s, and for a

time, he was Vidal's literary executor. In this collection of 20 essays

and an interview (which he conducted himself), Parini has assembled a

valuable anthology.

Parini's diverse book reprints chapters from the book-length studies by

White, Dick and Kiernan. Italo Calvino pens a salutation, commending Vidal

on his knowledge of and affection for Italy. Heather Neilson, an

Australian scholar who wrote a doctoral dissertation on Vidal, discusses

Messiah, as does the journalist/teacher Alan Cheuse. Stephen

Spender reflects on Gore Vidal: Private Eye, Louis Auchincloss on

Babylon Revisited (about the novel Hollywood), and

Harold Bloom discusses the big historical novel Lincoln.

Parini's diverse book reprints chapters from the book-length studies by

White, Dick and Kiernan. Italo Calvino pens a salutation, commending Vidal

on his knowledge of and affection for Italy. Heather Neilson, an

Australian scholar who wrote a doctoral dissertation on Vidal, discusses

Messiah, as does the journalist/teacher Alan Cheuse. Stephen

Spender reflects on Gore Vidal: Private Eye, Louis Auchincloss on

Babylon Revisited (about the novel Hollywood), and

Harold Bloom discusses the big historical novel Lincoln.

Together these essays are a mix of pure scholarship and intimate

reflection (from friends like Calvino and Auchincloss). "So what's going

on here?" Parini asks in his introductory essay. "Is Vidal a rather

old-fashioned realist? Is he anti-modern? Why has this postmodern

prototype been put on the shelf before he has, indeed, been taken off the

shelf?" Parini goes on to suggest reasons for this circumstance: Vidal's

unusually high productivity, his diverse canon, his insider approach to

his subject matter, and a "mandarin tone [that] relates not only to the

sense of the world as a fait accompli" but that "exists in every aspect of

the actual content." In short, Parini says, Vidal's way of writing, in

most of his fiction and all of his essays, leaves little room for the

reader to discern a subtext. "The tone is the essays," he

asserts. "It gives them their wonderfully acerbic edge and their

vitality." And while his best essays "somehow invite the reader to

participate in the 'knowingness' of it all," Parini recognizes that some

critics "recoil from this typically Vidalian stance."

Gore Vidal - L'iconoclaste (1997)

By Nicole Bensoussan

This is one of only two book-length study of Vidal's work written in a

language other than English (and, so far, not translated). The author is

French, and in her book, published by a university press, she studies the

political, religious and sociological undercurrents of Vidal's fiction and

nonfiction. Her chapter titles include "A Decadent Society,"

"Homosexuality and Alienation," "The Founding Father" and "Culture and

Religion." Her book focuses mostly on Vidal's work from the 1960s forward,

although she does spend eight pages discussing Messiah. She

concludes that despite the implacable irony and black humor of his work,

Vidal has a streak of Puritanism that seeks to expose the ills and

stupidity of society in an effort to edify Americans and save them from

deterioration.

Gore Vidal - A Critical Companion (1997)

By Susan Baker and Curtis S. Gibson

In their eclectic book, Professor Baker and her husband, "a nonacademic

enthusiast of Gore Vidal's work," parse Vidal's canon wearing a variety of

scholarly robes. By adopting different analytical postures for different

books, they give us new historicist readings of Julian and

Kalki; feminist readings of Burr, Lincoln and

Myra Breckinridge; deconstructive readings of Duluth,

Live from Golgotha and Creation; Marxist readings of

Empire and 1876; a psychoanalytic reading of

Hollywood; and an intertextual reading of Washington,

D.C.

The result is something like a survey course in literary analysis applied

to the work of one author, with each chapter written for the uninitiated:

The authors describe the plot and character development of each book

before launching into their analyses, thus you needn't have read the books

to follow the discussions. There's a biographical sketch up front, and

even a chapter that breezes through the early novels. Their work is

comprehensive and obviously admiring, making connections between the books

and with their influences rooted in Vidal's reading.

Gore Vidal: A Biography (1999)

By Fred Kaplan

English professor Kaplan's bountiful biography of Vidal is unsparing in

its detail and thorough in its evaluation of a writer whom one might call

- tongue firmly planted in cheek - the Forrest Gump of 20th Century

culture: Either directly or through small degrees of separation, Vidal

seems to have intersected the lives of virtually every literary,

political and cultural figure since his birth in 1925 at the U.S.

Military Academy at West Point. Kaplan writes about this busy life

journalistically in the broadest sense of the term: His biography is, on

the one hand, a detailed journal of Vidal's life, and on the other, a

rollicking good story, with vividly described characters and a climax to

virtually every chapter.

Vidal emerges as a successful, fortunate and maybe even rather ordinary

man of letters.

He wanted to be a writer, and so he worked diligently at it, winning

recognition in every medium he attempted. He did not destroy his life and

work with alcohol, ego, greed, anger, bitterness or depression, like so

many other writers one could name. He engaged life, but always somehow as

an outsider, which allowed him clearer eyes to write about it.

Vidal emerges as a successful, fortunate and maybe even rather ordinary

man of letters.

He wanted to be a writer, and so he worked diligently at it, winning

recognition in every medium he attempted. He did not destroy his life and

work with alcohol, ego, greed, anger, bitterness or depression, like so

many other writers one could name. He engaged life, but always somehow as

an outsider, which allowed him clearer eyes to write about it.

He has, in short, lived a vividly public life of the mind, expressed in a

voluminous body of work. As for the inner life, Vidal has always largely

kept such feelings to himself, and Kaplan doesn't fell compelled to drag

anything of him. From time to time it's evident in the biography -

carefully guarded, cautiously revealed, and still somewhat of a mystery.

Kaplan writes elegantly, presenting his metaphors with precision, and

summarizing each of his panoply of characters with shrewd analyses. For

the most part he treats Vidal's novels and plays as incidents in the life,

incorporating their plots and meanings as a part of the ongoing narrative,

not bothering at any length to parse the work, which is the realm of other

projects.

The Fiction of Gore Vidal and E.L. Doctorow (2002)

By Stephen Harris

In his somewhat unusual pairing, Harris presents "a close study of the

relationship between the individual and history - between a particularly

American idea of self and how this is experienced in relation to the

broader flow of events and time that shape human experience." The author

is Australian, and at the time of his book's publication, he taught

American literature, Australian literature and creative nonfiction at a

university in New Zealand. He now teaches at the University of New England

in New South Wales and is at work on Gore Vidal's Historical

Novels and the Shaping of American Political Consciousness, which

Mellen Press published in 2005.

Focusing, of course, on Vidal's historical novels - mostly the American

Chronicles, with references to Julian and Creation

- Harris revolves his book around the well-accepted assertion that "the

opposition between the individual and society attains a thematic

prominence" in American literature that is "dramatized as an antagonism

between the private subject and society: it is against the latter that the

individual offers resistance, performing self-perserving or self-defining

acts of rebellion, whether through escape, confrontation or rejection." He

then spends some time discussing this strain of American literature before

turning to his authors - Vidal first, then Doctorow. By "working with the

'disagreed- as well as agreed-upon facts," Harris writes, Vidal

"signals the desire to engage, critically and interrogatively, with

received accounts of the past - to use fictionalized history as a

counter-version through which we are prompted to actively re-view

history."

Vidal's work, he argues, shows how "the historical fact of power. . .can

so readily gather in and around an individual," and by "resurrecting"

Aaron Burr as a "revisionist mouthpiece on American history, Vidal not

only finds the ideal voice for his own skeptical views on what is said to

have happened and therefore on what America so often wants to believe

happened, but he also finds a figure who dramatizes, in a thoroughly

ironic manner, the fact that the individual can influence history - that

(to use his metaphor) the stage is always set for the appearance of the

Caesarian character in whom history moves."

Homosexuality in the Work of Gore Vidal (2002)

By Jörg Behrendt

Guess what this book is about? This interesting scholarly work,

written in

English by a German, and published by LIT Verlag of Hamburg, is a thorough

accounting of Vidal's homosexual-themed literature and his definitions of

homosexuality, copiously footnoted and with a lavish bibliography (36

pages) of works cited. In that regard, it is clearly the most exhaustive

piece of scholarship yet written about Vidal, although the author does not

entirely agree with Vidal's sociology.

Behrendt begins with a brief look at Vidal's public image and critical

reception. He then defines some key terms - "camp," "homophobia,"

"homosexual," "minority" - before offering a biographical sketch of

Vidal's life and books. Early in his story, Behrendt state that "Vidal's

playing with autobiographic details will become an important aspect when

evaluating the sexual identities expressed in his work.," although he

agrees with Vidal that is it not necessary to know whether

details of an author's work are taken from his life.

The bulk of Behrendt's book then reads the novels and essays to discern

"Vidal's Conception of Homosexuality," which "stands in opposition to much

of today's writing about homosexuality, which usually rather stresses the

positive aspects of Gay identities." Vidal, of course, attaches neither a

positive nor a negative to sexual orientation - to him, it merely exists

- and he believes that there is no such thing as a homosexual person, but

rather merely homosexual acts. Gently troubled by this view, Behrendt

notes: "Contrary to Vidal, many Gays find comfort within a Gay identity

and a Gay community." He then spends several pages discussing seminal

works of homosexual-themed literature, and he concludes about his titular

subject: "Vidal's conception of homosexuality does not always hold

together, and his novels do not in all points reflect his nonfictional

comments on homosexuality. However, at a time when anti-Gay discrimination

is on the rise again, Vidal's conviction of the fundamental equality of

homosexuals and heterosexuals, the naturalness of all stages of the sexual

continuum, is worth being reconsidered."

Gore Vidal's America (2005)

By Dennis Altman

Altman's enjoyable book - published in October 2005 by Polity Press, to

coincide with Vidal's 80th birthday - isn't largely

original scholarship on Vidal but rather a piece of research and

journalism that collects insights on several threads (i.e. themes) of

Vidal's life and work: his ideas about American imperialism; his ideas

about human sexuality; his ideas about the role of religion in society;

and so forth. He also discusses Vidal's lack of interest in writing

sociological or psychological novels. Although Altman presents his

material well, people already familiar with Vidal's work and the

scholarship on it will probably not come away from Gore Vidal's

America having a deeper understanding of Vidal's role as a

significant public figure, which Altman asserts early on is his goal.

Altman says he seeks to "demonstrate how Vidal 'embodies' a particular

critique of American society and politics, and, as part of this, seeks to

subvert both the triumphalist view of American history and mainstream

assumptions of sex and gender." He documents Vidal's work in these areas

well. But in the end, Altman demonstrates that Vidal has always been an

outsider and an iconoclast, rather than an icon or a trend-setter.

significant public figure, which Altman asserts early on is his goal.

Altman says he seeks to "demonstrate how Vidal 'embodies' a particular

critique of American society and politics, and, as part of this, seeks to

subvert both the triumphalist view of American history and mainstream

assumptions of sex and gender." He documents Vidal's work in these areas

well. But in the end, Altman demonstrates that Vidal has always been an

outsider and an iconoclast, rather than an icon or a trend-setter.

The author, who teaches politics at La Trobe University in Australia, and

who has known Vidal casually for 30 years,

has written before on Vidal: A long while back, he wrote an account of

Vidal's first visit to Australia. That piece appears in his book "Coming

Out in the Seventies" and is summarized in his book "Defying Gravity."

Altman's new book doesn't attempt to read Vidal's work in light of

literary theory and criticism (psychoanalytic, deconstructive,

post-modern, etc.). That would be another enterprise altogether. Instead,

it cites popular criticism (i.e., literary essays in general

circulation magazines, rather than scholarly journals) but very little

scholarly criticism. In fact, the book to which Altman compares his study

of Vidal is a book by a journalist: Garry Wills. Altman states his central

thesis in terms of Wills' book on John Wayne. But there's an essential

difference: Wayne influenced popular culture, and he was an

iconic figure; Vidal, on the other hand, seems to contradict

society, and thus he's an iconoclastic figure.

Later in his book, Altman breezes over what might have been the zenith

of Vidal's life as a public figure: His debate, on national

television, against William F. Buckley at the 1968 political

conventions. This gets one paragraph of mention in the text when such an

encounter might have been the focus of an entire chapter exploring Vidal

as public figure. In fact, Altman fails to quote a famous assertions of

Vidal's that might cast a light on why he's not an influential

public figure: For half a century, Vidal has claimed that "the novel is

dead." By this, he means that the novelist is no longer looked

upon as a cynosure in American culture. Had Altman explored this

assertion, it might have led him to examine Vidal's diminished role as

"public figure" and his emergence as, some would say, our National

Conscience.

N.B. Altman discussed his book on Australian radio in January 2006.

You can listen

to the interview if you have Real Player on your computer. And in

November 2005, Altman and Vidal appeared together at a Los Angeles book

store to discuss the book. At this link, you can

hear the interview and read about the event.

How To Be an Intellectual in the Age of TV:

The Lessons of Gore Vidal (2005)

By Marcie Frank

This trenchant and acessible scholarly study uses as its foundation

Vidal's famous

aphorism, "Never pass up the opportunity to have sex or appear on

television." Frank, a professor of English at Concordia University in

Montreal, opens her book with this sentence and then looks closely at

everything in Vidal's canon - in print and on film - that helps to

extricate its meanings and nuances. Thus her lens is an ideological

portmanteau of Altman's book, released just weeks before hers by another

publisher, and of Behrendt's, published several years earlier, but which

she doesn't cite in her endnotes. [See above for summaries of these two

books.]

"Vidal's idiosyncratic combination of patrician hauteur and radical

politics," Frank writes, "proves as hard to assess within the framework of

the American political spectrum as his attitudes toward sexuality do in

the framework of current literary or cultural analysis." This states the

dilemma well, although she does overlook a simple explanation: Vidal is

simply wrong about some things - for example, his long-standing assertion

that there is no such person as a "homosexual" (the word, Vidal argues, is

an adjective describing a behavior, not a noun describing an individual).

Her readings of Vidal's work find many illuminating links, although it's

quite odd that his 1954 novel Messiah gets only a passing mention

when it probably deserves an entire chapter. Begun in 1947 - well before

Marshall McLuhan published his most influential work on the role of media

in society - Messiah is the first text in which Vidal

explores medium-as-message.

simply wrong about some things - for example, his long-standing assertion

that there is no such person as a "homosexual" (the word, Vidal argues, is

an adjective describing a behavior, not a noun describing an individual).

Her readings of Vidal's work find many illuminating links, although it's

quite odd that his 1954 novel Messiah gets only a passing mention

when it probably deserves an entire chapter. Begun in 1947 - well before

Marshall McLuhan published his most influential work on the role of media

in society - Messiah is the first text in which Vidal

explores medium-as-message.

The value of Frank's book comes in how, within the context of her central

thesis, she unites the many tentacles of Vidal's body of work: his

American Chronicles, his "inventions," his nonfiction, his interest in

ancient history, and of course, his

appearances on television and in the movies. "The historical novels thus

provide the theory of his intellectual career," she writes, "while the

experimental novels provide the practice." She then traces this notion

through the writing and the life. Frank explores the movement away from

writers and toward university scholars as the honored intellectuals in our

culture. Vidal, she argues, "by supplementing the role of writer with

television," has managed to be both - and without shame or apology. And he

did so early in his career, when he recognized that the writer's role as

public intellectual was on the decline because of the media's rising

influence. Since then, in his fiction and nonfiction, he has explored

"the shift from print to screen modes of publicity," and he has

articulated a new harmony between "the pole of paranoia and romance,"

which Frank identifies as the two attitudes of traditional media

analysis.

"Vidal's public appeal," Frank writes, after a discussion of the American

Chronicles as "romance" novels, "rests on his ability to telecast and

write out of a position that does not cordon off serious literature from a

mass audience: rather, it brings Henry James and Jacqueline Susann

together. If Vidal maintains the status of exemplary American

writer-intellectual in the age of TV, it is because he has both exploited

the print-screen circuit in the genre of romance and found ways to

transmit his sexual politics on-screen."

Frank clearly recognizes that Vidal's two passions in life are politics

and human sexuality, the former because he grew up surrounded by it, and

the latter because he's a sexual outlaw himself. But he did not, as Frank

suggests, abandon the writing of "literary" novels merely because he

believed they were in decline. He abandoned them because, as he came to

better understand his own point of view, he naturally sought more

rewarding forms and mediums to express himself. Vidal once said that he

didn't expect readers in 1948 to associate the homosexuality of his

protagonist in The City and the Pillar with the author himself.

When they did, it forced him to re-evaluate the course of his life.

Vidal has certainly used the broadcast media to gain attention for his

political and cultural ideas, but he never actually used it to sell his

books. His novels Julian, Washington, D.C., Myra Breckinridge and

Burr became best-sellers on their own. His TV appearances in the

1960s through the 1980s largely followed the success of those

books, and many of his books along the way failed to attract readers

despite his notoriety. So it's something of an overstatement - or at

least, another matter altogether - when Frank asserts: "Vidal has

exploited electronic forms of publicity both to stay famous and to address

the divergence of the categories of literary author and

intellectual." All in all, Frank relies a bit too heavily on what

Vidal says about himself as she analyzes his literary and public lives.

She clearly seeks to reconstruct - rather than deconstruct - her subject.

Toward the end of her book, Frank neatly sums up and brings together its

threads. "Vidal's classicism consists of a universalizing understanding of

both sexuality and publicity accompanied by a strong sense of history that

registers changes in the status that has been accorded to each," she says.

"Against all expectations framed by the contemporary udnerstanding of TV,

Vidal is able to yoke classicism to TV, the vehicle through which his

politics (and sexual politics) frequently have been expressed." In other

words, Vidal is an orator, like an ancient Roman, and he uses both print

and moving pictures (film and TV) to orate on sex and politics, the two

subjects that most interest him (as they did his classical ancestors).

If Vidal has appeared so much on television, it's probably because, as

his aphorism implies, television is simply another form of instant

pleasure (and no doubt a stroke to his voluble ego). One doubts that his

sex life, the corollary to his broadcast life, did much to foster his

career. Quite the opposite, in fact, as Frank reminds us: The City and

the Pillar, so scandalous in its time, forced him to begin writing

pulp novels under pseudonyms and scripts for live television. And it's

certainly not true that "the pleasures of sex and appearing on TV are

interchangeable," as Frank writes. Vidal never said that, and one

hope that he's had far more of the former than the latter.

Gore Vidal's Historical Novels

and the Shaping of Political

American Consciousness (2005)

By Stephen Harris

In his 2002 book The Fiction of Gore Vidal and E.L. Doctorow,

Harris examined "the historical fact of power" as represented in Vidal's

historical novels. His new book, published by Edwin Mellen

Press, focuses on Vidal's works exclusively, taking a closer look

at how Vidal combines history and fiction.

A construção da memória da nação em José Saramago e

Gore Vidal (2006)

By Adriana Alves de Paula Martins

Like Vidal, the Portuguese writer José Saramago is a novelist, playwright

and essayist. And like Vidal, he looks at history in a way that mainstream

historians call subversive, searching beyond the recorded history. But

unlike Vidal he's won the Nobel Prize for literature (in 1998).

In her critical study - published in Portuguese, and so far not

translated into English - Martins compares the historical novels of the

two authors. The web site of the book's publisher, Peter Lang, says

that the book explores different models of post-modern historical fiction,

particularly the historical fiction of Saramago and Vidal, looking at how

the works reconstruct the historical memory of their respective nations.

The book is one of only two critical studies of Vidal's work published in

a language other than English. The title means "the construction of the

history of the nation in José Saramago and Gore Vidal."

In her critical study - published in Portuguese, and so far not

translated into English - Martins compares the historical novels of the

two authors. The web site of the book's publisher, Peter Lang, says

that the book explores different models of post-modern historical fiction,

particularly the historical fiction of Saramago and Vidal, looking at how

the works reconstruct the historical memory of their respective nations.

The book is one of only two critical studies of Vidal's work published in

a language other than English. The title means "the construction of the

history of the nation in José Saramago and Gore Vidal."

"The postmodern experience reflects a moment of crisis in the modernity

project that is translated into a crisis in the representation of the

empirical world," Martins writes of her work. "In historical terms, this

crisis results in a process of revision and reassessment of the

interpretation of the historical phenomenon. In literary terms, [it]

translates into the search for new aesthetic codes [that] informs the two

main currents of postmodern literary production: experimental fiction and

historical fiction." Her book seeks to show "how Vidal's and Saramago's

novels reveal the structure of the 'building' of the American and

Portuguese national memories," and "and how these processes promote the

rereading and rewriting of the past." She also explores the extent to

which the novels hold any hope for "intervention and historical

transformation."

Martins has also published a few essays on Vidal's work in various

journals and anthologies in both English and Portuguese: "Quotation and

Memory in Gore Vidal's Burr and José Saramago's The History

of the Siege of Lisbon," in the book In Dialogue with José

Saramago: Essays in Comparative Literature (co-edited with Mark

Sabine), as part of the Manchester Spanish & Portuguese Series, No. 18

(2006), pages 163-175; "O Cinema Americano e a Mentira da Guerra em

Hollywood de Gore Vidal," in the journal Máthesis, issue

No. 15 (2006), pages 1-9; and "O Verso e o Reverso da Medalha em

Lincoln de Gore Vidal," in the journal Máthesis, issue

No. 14 (2005), pages 255-268.

Gore Vidal: A Comprehensive Bibliography (2007)

Gore Vidal: A Comprehensive Bibliography (2007)

By S.T. Joshi

Robert Stanton's thorough bibliography of Vidal's work has been immensely

helpful in conducting Vidalian research since its publication in 1978. But

in the intervening years, Vidal has published many more books across

several genres, and he has seen his international popularity grow,

especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, which has allowed his work

to flourish in former communist countries.

S.T. Joshi - the author or editor of numerous books, including

Atheism: A Reader, which includes an essay by Vidal on American

fundamentalism - has updated the canon of research on Vidal with this new

and extensive bibliography. The book includes a foreword by Jay Parini,

Vidal's literary executor and himself the editor of a collection of

scholarly essays on Vidal.

Naturally, Joshi begins by listing all of Vidal's books in English

(U.S. and U.K.) along with a publication history that documents every

edition. For fiction, he briefly summarizes the plot; for essay

collections, he lists the contents of each book. Other sections in the

bibliography round up: articles and reviews by Vidal, briefly describing

the content; archival material at Harvard (the major repository) and other

locations; Vidal in the media; news items and encyclopedia listings about

Vidal and his family; interviews with Vidal; books and essays about Vidal;

and in a highly informative final section, major-media criticism and

reviews of Vidal's books, with concise summaries that excerpt many of the

reviews listed for each book. There are even brief sections listing web

sites and academic papers. A long introduction by the author walks the

reader through Vidal's personal and literary biography.

Joshi's section on foreign editions in his weakest. Although once again

greatly detailed - and certainly helpful to collectors - it overlooks

numerous editions, both older ones and more recent ones issued well before

Joshi's 2006 cutoff date. The section even fails to list three languages -

Korean, Slovak and Arabic - into which Vidal has been translated. Joshi

lists the Finnish edition Naiset kirjastossa ja muita kertomuksia

as a "translation of an unspecified work by Vidal." All it would have

taken to solve this mystery is a Finnish speaker to translate the title,

which means "The Ladies in the Library and Other Stories." This 1986 book

is, in fact, three stories selected from A Thirsty Evil, Vidal's

1956 collection of seven stories. The Finnish trilogy of stories was also

published in an English-language edition, which Joshi lists elsewhere,

incorrectly, as a reissue of the full seven-story 1956 collection.

No doubt a book this ambitious, involving so much research and minutiae,

was bound to have omissions and errors. It remains a valuable and very

interesting book, especially for its notations on the copious writing

about Vidal over the past half century.

Gore Vidal: A Bibliography, 1940-2008 (2009)

By Steven Abbott

Abbott began his association with Vidal in 1974, when he and John Mitzel

interviewed Vidal at length and published the interview in the magazine

Fag Rag and in the book Gore & Myra: A Book for

Vidalophiles (see above). Now, more than 35 years later, Abbott has

complied an exhaustively documented, two-volume bibliography of Vidal's

oeuvre. Abbott met with Vidal's agents and publishers during the

writing of the book, and he visited Vidal at his home in Ravello, Italy,

where he had access to Vidal's personal library. The book's publisher, Oak

Knoll Press, has a web page for the book that offers an excerpt, the table of

contents and a slide show of images.

Volume one of the bibliography is a book illustrated with more than 500

black and white images of Vidal's book covers and title pages. Volume two

is a CD-ROM that presents color images of the covers of many of Vidal's

books. Inside the printed edition, Abbott does more than just list Vidal's

books, plays, screenplays, magazine articles, interviews, juvenilia,

contributions to other books and more. He describes many of these

publications in copious detail.

Volume one of the bibliography is a book illustrated with more than 500

black and white images of Vidal's book covers and title pages. Volume two

is a CD-ROM that presents color images of the covers of many of Vidal's

books. Inside the printed edition, Abbott does more than just list Vidal's

books, plays, screenplays, magazine articles, interviews, juvenilia,

contributions to other books and more. He describes many of these

publications in copious detail.

This is not a book that one sits down to read cover to cover. It's a

reference guide that will last for generations as an encyclopedia of

Vidal's writing and the forms in which it was delivered to the public.

Each entry in the A section, for example, which details English-language

editions, describes each book in near microscopic detail. Throughout the

years Vidal has revised and republished some of his books, and Abbott has

read the original and revised texts page by page, creating easy-to-follow

charts that document the changes word by word.

The section on foreign editions has more than 400 individual entries,

including citations for Vidal's writing that has been translated into

Braille. For the convenience of the reader, Abbott lists foreign editions

in two ways: language by language, for people researching all of Vidal's

books in a particular language; and title by title, for people researching

all of the translations of a particular book.

Abbott also includes a lengthy chronology of Vidal's life and work, and a

voluminous section on Vidal's writing in periodicals, his writing for

television and the movies, and writing about him in magazines and books.

It's a definitive work for literary scholars and Vidalophiles.

In Bed with Gore Vidal:

In Bed with Gore Vidal:

Hustlers, Hollywood, and the

Private World of an American Master (2013)

By Tim Teeman

Gore Vidal never referred to himself as "gay" and bristled at anyone who

did. He always asserted that all people are bisexual - some practicing,

some not. Of his tell-all book, due to be published in November 2013, Teeman

says, "Vidal's friends and family talk about not just the sex Vidal

had and with whom, but the roots of his complex attitude towards sexuality

and love which lay in a fractured upbringing, and why his refusal to be

defined was as personal as it was intellectual. He may have been

"post-gay" before his time, but Vidal was also of his time.when being

"gay" meant being effeminate, an outsider, without power. Vidal did not

identify with any of those positions and wasn't in thrall to the equality

movement. He had grown up around power - his much-loved grandfather was a

senator - and he coveted his relationship with John and Jackie Kennedy

(whom he was related to) before they fell out, he claimed because Bobby

Kennedy believed Vidal's sexuality could become a White House

embarrassment."

Political Animals: Gore Vidal on Power (2015)

By Heather Neilson

An Australian scholar and teacher, Neilson began writing about Vidal in

the 1980s while getting her doctorate at Oxford, and her essay on

Messiah, adapted from her dissertation, appears in the 1992

book

Gore Vidal: Writer Against the Grain, edited by Jay Parini (see

above). She has published numerous articles about Vidal's work throughout

the years, including "The Friendly Ghosts in Gore Vidal" (2011), "A

Theatre of Politics: History's Actors in Gore Vidal's Empire"

(2008), "In Epic Times: Gore Vidal's Creation

Reconsidered" (2004), "Jack's Ghost: Reappearances of John F. Kennedy

in the work of Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer" (1997) and "Live from

Golgotha: Gore Vidal's Second 'Fifth Gospel'" (1995).

Neilson's book, her first on Vidal, will draw upon her dissertation and

her more recent thinking about his work as she looks at Vidal's

representations of leaders and historical figures (political, military and

religious), and how Vidal uses such people to explore the nature of power

structures. And because Vidal writes about the influence of media in

politics, so will her book.

Here's how the publisher describes it: "The late Gore Vidal occupied a

unique position within American letters. Born into a political family, he

ran for office several times, but was consistently critical of his

nation's political system and its leaders. A prolific writer in several

genres, Vidal was also widely known - particularly in the US - on the

basis of his frequent appearances in the various electronic media. This

ground-breaking work examines the centrality of the theme of power

throughout his writings. Political Animal: Gore Vidal on Power focuses

primarily, although not exclusively, on Vidal's historical fiction. In his

novels depicting American history, and those set in the ancient world,

Vidal evokes a world in which deliberately propagated falsehood

('disinformation') can become established as truth. The book engages with

Vidal's representations of political and religious leaders, and with his

deeply ambivalent fascination with the increasingly inescapable influence

of the media. It asserts that Vidal's oeuvre has a Shakespearean resonance

in its persistent obsession with the question of what constitutes

legitimate power and authority."

Sympathy for the Devil: Four Decades of Friendship with

Gore Vidal (2015)

By Michael Mewshaw

In this well-titled book, the writer - who has published journalism,

nonfiction, fiction and literary criticism - looks vividly and frankly at

the life of his generous, difficult, long-time friend. Filled with

anecdotes and tart observations, it's a vividly written memoir about

friendship and fame.

"Alcohol, massive amounts of it consumed over decades, did him

incalculable damage, raving his physical and psychological equilibrium,"

Mewshaw writes. "This, it might be argued, was his private business. But

because drinking undermined his work and his public persona, I believe

that this topic and his long-standing depression deserve discussion."

Whether it undermined his work - at least for most his life - is

certainly not settled personal history. But Vidal's alcoholism and

depression have rarely been approached, and learning about it here gives

new dimension to a man seen by so many as being haughty and aloof. Mewshaw

says his book is not (borrowing Joyce Carol Oates' term) a "pathography,"

which he describes as "a lurid post-mortem that dwells on an author's

deterioration." It's a more personal tale that takes a balanced and humane

look at his gifted friend.

Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal (2015)

By Jay Parini

A teacher, novelist and scholar, Jay Parini of Middlebury College had been

friends with Vidal for 30 years before Vidal's death, and he was Vidal's

literary executor for a time. His biography draws on some memories of that

long friendship, but it's not an autobiography. In fact, Parini combines

observations about Vidal's novels and essays with his breezy retelling of

his life story. Shortly before the book's publication, Parini wrote a piece for the U.K. Guardian about his friend

and subject's often-contentious life.

Return to the Gore Vidal

Thumbnails introduction

Return to the Gore Vidal

Thumbnails introduction

If you came right to this thumbnail page and don't see a frame on the

left, please visit The Gore Vidal

Index now or after you've enjoyed the thumbnails, which you can access

from the main index page. And please send me comments if you have a thought, a suggestion

or a link to add to the index.

©Copyright 2007 by

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

kloman@pitt.edu

So the stage is set for a generous and experienced reading of Vidal's work

through Burr, a good stopping point. Dick gives his chapters

amusing titles, like "A Portrait of the Artist as G.I. Joe," "Huck Honey

on the Potomac," "Manchild in the Media," "The Hieroglyphs of Time" and

"Myra of the Movies; Or, the Magnificent Androgyne." Unique among studies

of Vidal's work, he addresses the juvenilia: poems and short stories

published when Vidal was a teen-ager, before he graduated from high school

and entered the Army. He even reprints three poems, using this passage of

his book to recount some brief biography, but always focusing on the

writing rather than the life.

So the stage is set for a generous and experienced reading of Vidal's work

through Burr, a good stopping point. Dick gives his chapters

amusing titles, like "A Portrait of the Artist as G.I. Joe," "Huck Honey

on the Potomac," "Manchild in the Media," "The Hieroglyphs of Time" and

"Myra of the Movies; Or, the Magnificent Androgyne." Unique among studies

of Vidal's work, he addresses the juvenilia: poems and short stories

published when Vidal was a teen-ager, before he graduated from high school

and entered the Army. He even reprints three poems, using this passage of

his book to recount some brief biography, but always focusing on the

writing rather than the life.