FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

For three generations, politics was a family business for the Gores and the Vidals, although in the case of Gore Vidal, it never paid the bills.

Vidal's grandfather, Thomas P. Gore, was a popular (and populist) senator from Oklahoma - the state's first senator, and the Senate's first blind member. He served from 1907-1921 and again from 1931-37, losing his bid for renomination in 1920 to a fellow Democrat because he opposed the League of Nations, and losing in '36 because of his opposition to the popular FDR. (In between, he returned to private law practice.) As a child, the young Vidal would often accompany his grandfather to the floor of the Senate, occasionally being permitted to sit in the chair reserved for the vice president.

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

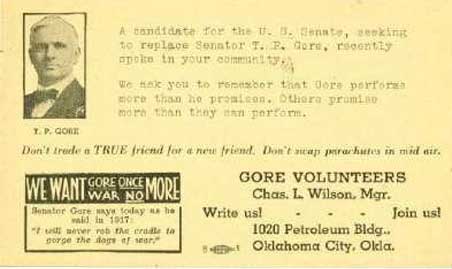

At right is a campaign post card that Sen. Gore sent to constituents

during his losing 1936 re-election bid. "Don't trade a TRUE friend for a

new friend," says the card. "Don't swap parachutes in mid air." Touting

his well-known, anti-interventionist, anti-foreign-war stand - and

borrowing from Shakespeare as he does it - the senator promises: "I will

never rob the cradle to gorge the dogs of war." He lost the election, thus

ending his political career. (Vidal would later base the character of the

FDR-hating Sen. James Burden Day in his 1967 novel, Washignton,

D.C., on his grandfather.) At left is a badge signed by Sen. Gore to

permit his guest to enter the Senate chambers. Or you can see a page from the

Congressional Record with a speech by Sen. Gore. (The

slide show presents three pages of the speech.)

At right is a campaign post card that Sen. Gore sent to constituents

during his losing 1936 re-election bid. "Don't trade a TRUE friend for a

new friend," says the card. "Don't swap parachutes in mid air." Touting

his well-known, anti-interventionist, anti-foreign-war stand - and

borrowing from Shakespeare as he does it - the senator promises: "I will

never rob the cradle to gorge the dogs of war." He lost the election, thus

ending his political career. (Vidal would later base the character of the

FDR-hating Sen. James Burden Day in his 1967 novel, Washignton,

D.C., on his grandfather.) At left is a badge signed by Sen. Gore to

permit his guest to enter the Senate chambers. Or you can see a page from the

Congressional Record with a speech by Sen. Gore. (The

slide show presents three pages of the speech.)

In the 1930s and 1940s, Vidal's father, Eugene L. Vidal, served as the first director of the Bureau of Air Commerce in the Roosevelt administration. He was a pioneer aviator and a close friend of Amelia Earhart.

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

With this family history, and with his astute political mind, no wonder Gore Vidal eventually decided to run for public office himself. In the 1940s, Vidal's grandfather had hoped to help his grandson establish himself in New Mexico, where he would then run for public office and begin to build his political career. But when Vidal took off for Guatemala to write, and when he published his gay-themed novel The City and the Pillar in 1948, Sen. Gore's political hopes for his grandson vanished.

By 1960, the dust had settled somewhat from the scandals of his youth, so

Vidal ran for the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat in the

heavily Republican Dutchess County, the district in upstate New York where

he lived. Sen. John F. Kennedy, the Democratic nominee for president, came

to campaign for him, as did former President Harry S Truman. He lost the

election but still got more votes than Kennedy did in Dutchess County.

Immediately afterwards, friends and politicos urged him to gear up for the

'62 races for Congress, possibly even for a Senate race. But he declined.

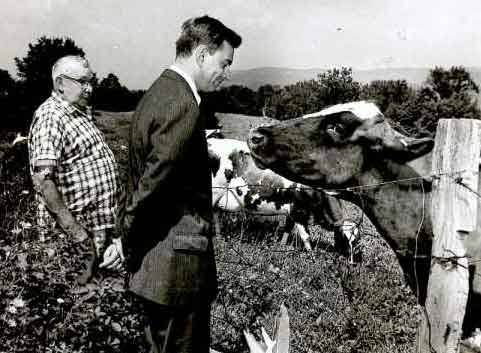

The race in rural upstate New York, however, did introduce Vidal to a wide

range of constituents in his district, and pictured at left is a

photographic reminder of what some candidates will do to get close to "the

people." And just below, at right, Vidal and Kennedy appear together on

the campaign trail in 1960, signing autographs and greeting well-wisher.

By 1960, the dust had settled somewhat from the scandals of his youth, so

Vidal ran for the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat in the

heavily Republican Dutchess County, the district in upstate New York where

he lived. Sen. John F. Kennedy, the Democratic nominee for president, came

to campaign for him, as did former President Harry S Truman. He lost the

election but still got more votes than Kennedy did in Dutchess County.

Immediately afterwards, friends and politicos urged him to gear up for the

'62 races for Congress, possibly even for a Senate race. But he declined.

The race in rural upstate New York, however, did introduce Vidal to a wide

range of constituents in his district, and pictured at left is a

photographic reminder of what some candidates will do to get close to "the

people." And just below, at right, Vidal and Kennedy appear together on

the campaign trail in 1960, signing autographs and greeting well-wisher.

In the late 1960s, Vidal helped form the New Party, which later changed

its name to the People Party. Eugene McCarthy and Ralph Nader were fellow

party members and, at times, party candidates. But Vidal himself only

tried politics once more when he ran for

the U.S. Senate in California in 1982. In a field of 10 candidates, he

lost to Jerry Brown, who subsequently lost in the general election to Pete

Wilson. Brown got 45% of the vote in the primary to Vidal's 15%. Vidal

cast himself as the "serious alternative" to more status-quo candidates

like Brown, and his bid was the subject of Gore Vidal: The Man Who

Said No, a documentary film by Gary Conklin. At the time he ran,

Vidal lived at least half of the year at his villa in Italy. But he never

sold his home in California and so remained a U.S. taxpayer and a

constituent of the state. Even so, Vidal rarely donates money to political

campaigns: According to the records of the Federal Election Commission, he

has only made

two contributions to political candidates since 1980.

In the late 1960s, Vidal helped form the New Party, which later changed

its name to the People Party. Eugene McCarthy and Ralph Nader were fellow

party members and, at times, party candidates. But Vidal himself only

tried politics once more when he ran for

the U.S. Senate in California in 1982. In a field of 10 candidates, he

lost to Jerry Brown, who subsequently lost in the general election to Pete

Wilson. Brown got 45% of the vote in the primary to Vidal's 15%. Vidal

cast himself as the "serious alternative" to more status-quo candidates

like Brown, and his bid was the subject of Gore Vidal: The Man Who

Said No, a documentary film by Gary Conklin. At the time he ran,

Vidal lived at least half of the year at his villa in Italy. But he never

sold his home in California and so remained a U.S. taxpayer and a

constituent of the state. Even so, Vidal rarely donates money to political

campaigns: According to the records of the Federal Election Commission, he

has only made

two contributions to political candidates since 1980.

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

FEATURED PAGE: A

slide show of political Vidaliana

Vidal has long asserted that he's related to family of Al Gore, the former senator, former vice president and, if popular votes counted, 42nd president. Vidal's grandfather once wrote that he and Al Gore's father were seventh cousins, making Gore Vidal and Al Gore - well, some level of ordinal cousins or another. But a genealogist has constructed a very thorough genealogy of the family of Al Gore and finds no traceable relationship between Al Gore and Gore Vidal. The last three paragraphs of this genealogical chart discusses the matter. [A web site with the chart has been removed from the internet and is no longer available for viewing.] There's also another genealogist who asserts that his research can find no crossing between the two families whose name each happens to be Gore.

Although Vidal never won elective office, he wrote three election-year

plays about politics. The most distinguished of these, The Best

Man, debuted on Broadway on March 31, 1960, to strong reviews. It ran

for an impressive 520 performances. The play was revived on Broadway

during the 2000 presidential elections. His 1968 political play,

Weekend, didn't do so well, opening on March 13, 1968, and

closing 22 performances later. Finally, in 1972, Vidal wrote the caustic

comedy An Evening with Richard Nixon and. . ., which opened April

30 and ran for a bleak 17 performances. Among the members of the cast was

a young Susan Sarandon, who became good friends with Vidal. Years later,

Sarandon's partner, the actor/director Tim Robbins, cast Vidal as a

stately old liberal senator in his film Bob Roberts (1991). At

last, Vidal could share the honored title with his famous grandfather.

Although Vidal never won elective office, he wrote three election-year

plays about politics. The most distinguished of these, The Best

Man, debuted on Broadway on March 31, 1960, to strong reviews. It ran

for an impressive 520 performances. The play was revived on Broadway

during the 2000 presidential elections. His 1968 political play,

Weekend, didn't do so well, opening on March 13, 1968, and

closing 22 performances later. Finally, in 1972, Vidal wrote the caustic

comedy An Evening with Richard Nixon and. . ., which opened April

30 and ran for a bleak 17 performances. Among the members of the cast was

a young Susan Sarandon, who became good friends with Vidal. Years later,

Sarandon's partner, the actor/director Tim Robbins, cast Vidal as a

stately old liberal senator in his film Bob Roberts (1991). At

last, Vidal could share the honored title with his famous grandfather.

ęCopyright 2005 by

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

kloman@pitt.edu