Gore Vidal's Works for the Theater: 1956-1972

Gore Vidal became a playwright somewhat by accident. After the 1948

publication of his gay-themed novel The City and the Pillar,

major mainstream newspapers and magazines refused to review his subsequent

novels and so they

didn't sell very well. To supplement his income, he wrote five pulp novels

under three different

pseudonyms. He also turned to writing scripts for the emerging medium

of television, which had come to specialize in live drama and thus offered

satisfying work to serious writers like Vidal. This work lead him to write

screenplays for Hollywood films, and eventually to Broadway when one of

his live teleplays - the darkly humored science-fiction political satire

Visit to a Small Planet, so impressed critics and audiences that

a producer invited him to turn it into a theatrical play.

Gore Vidal became a playwright somewhat by accident. After the 1948

publication of his gay-themed novel The City and the Pillar,

major mainstream newspapers and magazines refused to review his subsequent

novels and so they

didn't sell very well. To supplement his income, he wrote five pulp novels

under three different

pseudonyms. He also turned to writing scripts for the emerging medium

of television, which had come to specialize in live drama and thus offered

satisfying work to serious writers like Vidal. This work lead him to write

screenplays for Hollywood films, and eventually to Broadway when one of

his live teleplays - the darkly humored science-fiction political satire

Visit to a Small Planet, so impressed critics and audiences that

a producer invited him to turn it into a theatrical play.

Vidal's first drama for live television, Dark Possession, aired

Feb. 15, 1954, on CBS' weekly series Studio One. Three months

later came Smoke, an adaptation of a story by William Faulkner

done for the series Suspense, again on CBS. And three months

after that, again for Suspense, came Barn Burning,

another Faulkner adaptation. In all, he got paid well for writing 16

script for various CBS and NBC live dramatic series between 1954 and 1960.

His teleplays included many adaptations of noted writers, among them

Ernest Hemingway (A Farewell to Arms), Henry James (The Turn

of the Screw), Stephen Crane (The Blue Hotel), and Robert

Louis Stevenson (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). He even adapted

himself as the pseudonymous mystery writer Edgar Box, turning Death in

the Fifth Position into the dramatic thriller Portrait of a

Ballerina. His work as a writer for television turned very personal

on Dec. 13, 1959, when he wrote and narrated The Indestructible Mr.

Gore, a dramatic tribute to his grandfather, Sen. Thomas P. Gore of

Oklahoma. [This excellent web site provides a thorough listing of

Vidal's teleplays and where you can see them on archival tapes.]

During this period of his life, and continuing for more than 30 years,

Vidal dabbled in Hollywood screenwriting, usually for the money and most

often with mixed results because of the collaborative and commercial

nature of mainstream cinema. For his first screenplay he adapted Paddy

Chayefsky's well-received television play Wedding Breakfast,

opening up the drama in a way that marked it somewhat as his own. The

movie came to theaters in 1956 as The Catered Affair. Then he

adapted Nicholas Halasz's book I Accuse!, about the Dreyfus

trial, followed by adaptations of Tennessee Williams (Suddenly, Last

Summer) and Daphne du Maurier (The Scapegoat). In the late

1950s, he spent some time rewriting portions of the script for

Ben-Hur, injecting a subtle homosexual undercurrent in one scent

that, to this day, Charlton Heston denies exists. He wrote an original

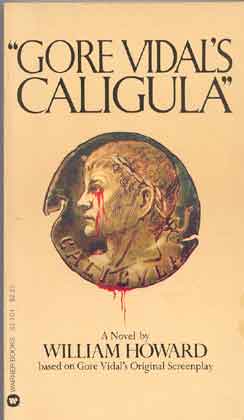

screenplay about the Roman emperor Caligula in 1979 that

Penthouse publisher and "movie producer" Bob Guccione turned into

a high-class piece of pornography - which Vidal disowned. And in 1986, he

penned a well-received, four-hour television adaptation of Lucien

Truscott's military thriller Dress Gray.

movie came to theaters in 1956 as The Catered Affair. Then he

adapted Nicholas Halasz's book I Accuse!, about the Dreyfus

trial, followed by adaptations of Tennessee Williams (Suddenly, Last

Summer) and Daphne du Maurier (The Scapegoat). In the late

1950s, he spent some time rewriting portions of the script for

Ben-Hur, injecting a subtle homosexual undercurrent in one scent

that, to this day, Charlton Heston denies exists. He wrote an original

screenplay about the Roman emperor Caligula in 1979 that

Penthouse publisher and "movie producer" Bob Guccione turned into

a high-class piece of pornography - which Vidal disowned. And in 1986, he

penned a well-received, four-hour television adaptation of Lucien

Truscott's military thriller Dress Gray.

By 1956, Vidal had established himself as a successful writer of

television drama. He edited a book, Best Television Plays, that

included his own Visit to a Small Planet, along with teleplays by

seven other famous television writers of the day, among them Rod Serling,

Paddy Chayefsky, Horton Foote and Tad Mosel. Also that year, Vidal

published Visit to a Small Planet and Other Television Plays,

collecting eight of his own live dramas. In his Foreword to the

collection, he confessed his reticence about writing for television: "The

novel is the more private and (to me) the more satisfying art. A novel is

all one's own, a world fashioned by a single intelligence, its reality in

no way dependent upon the collective excellence of others. Also, the

mountbankery, the plain showmanship, which is necessary to playwriting

inevitably strikes the novelist as disagreeably broad. Even the dialogue

is not the same in a novel as it is on the stage. Seldom can dialogue be

taken from a book and played by actors. The reason is one of pace rather

than of verisimilitude."

mountbankery, the plain showmanship, which is necessary to playwriting

inevitably strikes the novelist as disagreeably broad. Even the dialogue

is not the same in a novel as it is on the stage. Seldom can dialogue be

taken from a book and played by actors. The reason is one of pace rather

than of verisimilitude."

And yet, Vidal persisted, quite successfully and very profitably, in this

mode: During the 1950s, he became known as a talented author of television

scripts, one of which, The Death of Billy the Kid starring Paul

Newman, became a feature film, retitled The Left-Handed Gun.

Although Newman recreated his television role, Vidal did not write the

screenplay and later disowned the film, claiming that it compromised his

vision of the characters. Some 30 years later, he had another crack at the

story when he wrote the television script for Gore Vidal's Billy the

Kid, with Val Kilmer in the title role and Vidal appearing in a cameo

as a preacher. Another of his teleplays, Honor, aired in 1956 and

became - in longer form - a short-lived theatrical production under the

title On the March to the Sea.

From this almost accidental foray into television drama grew Vidal's work

as a playwright for Broadway, a career that began in 1957, reached its

zenith in 1960, and continued through the early 1970s. All of these plays

were published in one form or another, with the sole exception of A

Drawing Room Comedy, which was produced outside of New York in 1970

and never made it to Broadway. Vidal has not seen a new play of his

produced since 1972, although his 1960 hit The Best Man was

revived on Broadway in 2000 for a limited election-year run, impressively

retitled Gore Vidal's The Best Man. The experience so pleased him

that he's reportedly now at work on a play about Aaron Burr, adapting his

own 1973 novel on the scandalous vice president. He also revised and

revived his early 1960s play On the March to the Sea for a series

of staged readings in 2004-05.

Visit to a Small Planet (1957)

Kreton, a visitor from a far-away planet with a culture and a technology

far more advanced than ours, comes to Earth to witness what Earthlings do

best: make war. Unfortunately, his time-and-space-traveling craft landed

in 1950s America rather than during the Civil War - for which he came

appropriately dressed. Nonetheless, Kreton is determined to see a war,

even if he has to start one himself, which causes great distress for the

Spelding family with whom he's taken up temporary residence. And they'd

better watch what they think about their visitor: He can read minds -

including the mind of the family cat. As it turns out, Kreton is

considered to be a child on his home world, so his infatuation

with warfare - just like ours here on Earth - is ultimately

revealed to be the interest of a puerile mind.

In its time, satire like this was rather progressive - three sponsors

rejected the original teleplay before it finally came to TV - although

today the play seems to be more amusing than provocative. The

science-fiction world lauded the work because its success on television

and Broadway marked a popular breakthrough for the genre. The play

opened

on Broadway at the Booth Theater on Feb. 7, 1957, and ran for a very

successful 388 performances, all starring the distinguished actor Cyril

Ritchard, who created the role of Kreton on television and revived in the

Broadway play, which he also directed. Vidal published Visit to a

Small Planet in hardcover in 1957, and the complete text of the play

appeared in several magazines, including the March 1957 issue of The

Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. The text even appeared in

Speculations, a 1973 science-fiction anthology textbook for high

school students. Jerry Lewis starred in a 1960 movie version of the play -

not adapted by Vidal - which had little to do with Vidal's original and

which Vidal disowned at the time of its release.

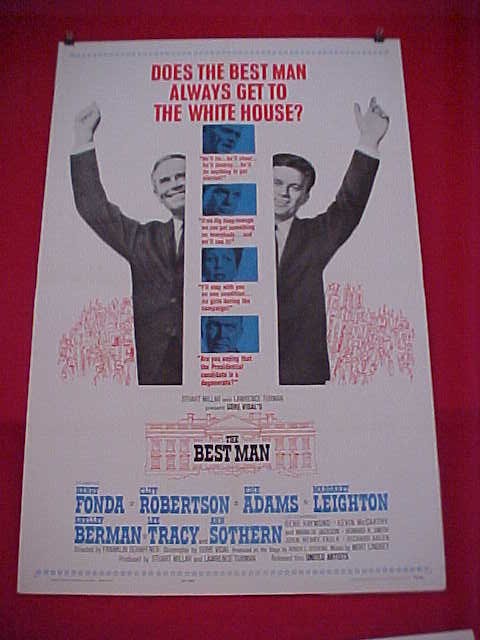

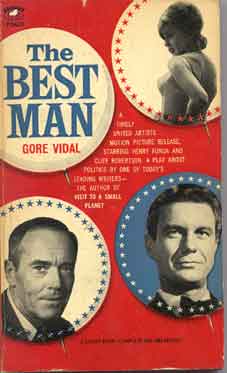

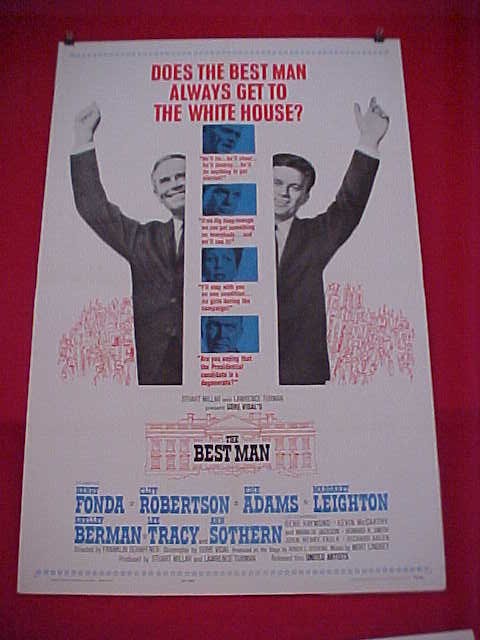

The Best Man (1960)

Vidal's most highly regarded and trenchant play naturally deals with

politics. It's an election year, and President Arthur Hockstader (Lee

Tracy) cannot run for re-election. He's also dying, so he has an eye

toward history and toward selecting his successor. Who will it be? There's

William Russell (Melvyn Douglas), an honest man of high moral values and

great intellect (think of Adlai Stevenson). And there's Sen. Joseph

Cantwell (Frank Lovejoy), a gamesman who knows what it takes to get what

he wants. Will Cantwell use potentially damaging true material about

Russell against him? Will Russell retaliate by using potentially damaging

but almost certainly untrue material about Cantwell against him?

And who will the dying president endorse: the man he trusts, or the man he

thinks can win the election?

but almost certainly untrue material about Cantwell against him?

And who will the dying president endorse: the man he trusts, or the man he

thinks can win the election?

The Best Man opened on Broadway at the Morosco Theater on March

31, 1960, and ran for a

strong 520 performances, making it one of the dramatic hits of the season.

By 1964, Vidal had written a screenplay of the story that would become the

only

theatrical movie of his career that fully pleased him. The film cast Henry

Fonda as good candidate Russell and a steely Cliff Robertson as the

corrupt Sen. Cantwell. Lee Tracy reprised his role as the dying President

Hockstader. It's a fine film even today, sharply acted and directed (by

Franklin Schaffner), well worth the rental fee and reasonably priced to

own, thus a rare opportunity to see some of Vidal's theatrical work

preserved on film.

Vidal published the play in book form in 1960 and, like Visit to a

Small Planet, the text has appeared in several anthologies.

Throughout the years, Vidal revised the script of the play, taking out

dated historical references and replacing them with updated ones. The

currently available Dramatist Play Service playscript sets the drama in

July

1976, rather than the original July 1960. But in the fall of 2000, for

a Broadway revival of the play during the Gore/Bush presidential

election

season, Vidal returned to his original 1960 script rather than updating it

once again. That production - the first on Broadway since its 1960 debut -

starred Spalding Gray as Russell, Chris Noth as Cantwell, and Charles

Durning as President Hockstader. Reviews were generally positive and the

play finished its limited engagement, which lasted through December - only

slightly longer than the Bush/Gore election itself.

On the March to the Sea (1960-61)

Honor, a Civil War drama, aired on the NBC series Playwrights

'56 on June 19, 1956. It told the story of a dignified Southern

gentleman who instills high moral values in his sons, but who, when

confronted with the opportunity to live up to his own standards, finds

himself uncertain of the proper road to chose. The next year, Vidal got

the notion to expand the play for Broadway. He wrote the script on and off

for the next few years, and finally, in 1960, prepared the play for an

opening at the Hyde Park Playhouse, not far from where he lived in Hudson,

N.Y., with an eye toward taking it to Broadway.

There's now some dispute about whether the 1960 production ever saw an

audience. In a 2005 statement, issued at the time of a revival of the

play, Vidal said that "the original play was never performed in English,"

casting doubt on whether the Hyde Park production ever opened. But Robert

Stanton, in his 1980 bibliography of Vidal's work, said the play opened in

the summer of 1960 in Hyde Park; and Vidal's biographer, Fred Kaplan, said

that production got mixed to negative reviews and so never made it to

Broadway, closing after a few weeks in Hyde Park, sustaining itself for

that long on Vidal's name, and losing Vidal his $6,000 investment in the

production. Vidal and Stanton agree that the play got a staging in Bonn,

Germany, the following year. The script for the German production was

published as Flammen zum Meer.

Although unappreciated in the U.S., this minor play still appeared in

print as part of Three Plays, a hard-to-find 1962 British

hardcover book that includes Visit to a Small Planet and The

Best Man. In his short preface to the published text, Vidal says of

the play: "I have included this faulty play not only because I have spent

several years trying to get it right and I hate to think so much time was

spent to no use, but because, despite faults, it has some interest, even

in this version." Three Plays subtitles the drama "A Southern

Tragedy."

On the March to the Sea got a second life in 2004-05 with a

series of modest revivals in smaller venues. In October 2004, a theater

company in Hartford, Conn., conducted a staged reading of the play with

Chris Noth - noted for his roles on TV's Law & Order and Sex

and the City - portraying one of the characters. Noth had appeared in

the 2000 Broadway revival of Vidal's The Best Man and clearly

retained an affection for the author. This Hartford reading led to a staged

reading of the play in February 2005 at the Reynolds Theater on the

campus of Duke University in Raleigh-Durham, N.C. For these revivals,

Vidal said he "rewrote the entire play, adding a new Colonel Thayer to the

narrative." Noth played the lead in the Duke production, and Vidal spent

time in North Carolina during rehearsals and for the premiere. There's no

word on whether it will move to New York, although that was Vidal's

intention during the revival at Duke. Interestingly, all of the press

surrounding the Hartford and Duke productions referred to the "world

premiere" of Vidal's "new" play, the writers apparently unaware of the

drama's history. A piece in Playbill

finally set the record straight - with the help of a noted Vidal scholar.

Incidentally, Vidal's Honor is an interesting footnote in the

history of live television drama, which only lasted for a few years in the

1950s: According to Vidal, the final package of live TV dramas ever

produced was NBC's Playwrights '56, and the final drama in

that series was Honor. Thus Vidal wrote the swan song for a genre

that gave American culture such writers as Paddy Chayefsky, Rod Serling,

Horton Foote, Reginald Rose and Tad Mosel.

Romulus (1962)

To tell a story about the last days of the life of Romulus Augustus, who

served as ruler of the Western Roman Empire from 475-476 A.D. - the last

year of its existence -Vidal adapted Friedrich Duerrenmatt's play

Romulus der Gr��e. He embarked on this project after meeting

Duerrenmatt in 1959 and suggesting to the German author the idea of a

Vidalian adaptation of one of his plays. The play dealt with themes close

to Vidal's heart: history, politics and power - themes he would revisit

two years later in his novel Julian, the story of another Roman

emperor. The drama of Romulus opens with the Goths at the gate

of an empire on the brink of collapse - and with Emperor Romulus more

than happy to let it happen (for reasons of his own).

Romulus, like the fated ruler whose short reign it chronicles,

had a fleeting run on Broadway: It opened on Jan. 26, 1962, at the Music

Box Theater and closed 69 performances later. Cyril Ritchard starred at

Romulus, but the actor and the playwright could not recapture the success

of their collaboration on Visit to a Small Planet. Some critics

of the time blasted the play for being unfaithful to Duerrenmatt's darkly

majestic drama, claiming Vidal had made it frivolous with his adaptation.

So to set them straight, he published the complete text of the play in a

1966

hardcover edition that also included a translation of Duerrenmatt's

original.

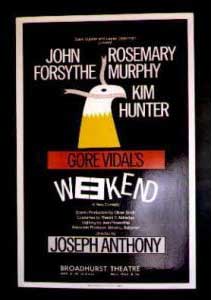

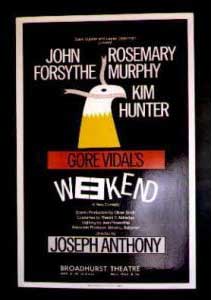

Weekend (1968)

Vidal made a moment of broadcast history in 1968 during the Democratic

National Convention when, on live television, he and William F. Buckley

came to blows. Seated with the taciturn ABC newsman Howard K. Smith

between them, Vidal taunted Buckley with liberal opinions and stinging

epithets. His anger mounting, Buckley finally lashed out: "Listen, you

queer," he said, "stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I'll punch you in your

goddamned face and you'll stay plastered." The lawsuits between the two

men, exacerbated by their versions of the encounter published in

Esquire, went on for years.

If only Vidal's 1968 political play Weekend had generated so much

excitement. The play opened March 13, 1968, at the Broadhurst Theater and

closed after a paltry 22 performances, earning largely hostile reviews

(although Washington audiences and critics liked it). Kim Hunter and John

Forsythe graced the cast. The play, set in the Rock Creek Park home of

Sen. Charles MacGruder, tells a familiar and tart Vidalian story of

political ambition and amorality. Rife with contemporary references,

including remarks about Vietnam and President Lyndon Johnson, the play

reportedly so upset one of the president's daughters that she left in the

middle of a performance. Vidal himself grew up in Rock Creek Park - in the

home of his grandfather, Sen. Thomas P. Gore. So the setting of

Weekend is clearly autobiographical even if the action is not.

The play was never published as a book but remains in print as a

playscript available from Dramatist Play Service.

A Drawing Room Comedy (1970)

Vidal must have been in a weird place when he wrote this little two-act

comedy in the mid-1960s. He completed the play around 1970, and although

it was staged briefly outside of New York, it never made it to Broadway

and its script was never commercially published. What begins as an

insouciant post-dinner-party conversation in the drawing room of a wealthy

Manhattan home soon takes turns for the surreal and the absurd. It's Edgar

Box meets Pirandello meets Noel Coward meets Coming Through the

Rye, William Saroyan's 1942 one-act play about - well, the un-dead.

The play has six characters: Norman, who just left a job as an anti-Commie

propagandist for a government information agency, and who now works in

public relations for a television network; his wife, Grace; another

couple, the husband Jewish, the wife Norman's extra-marital lover of 10

years; a retired admiral in his 60s; and Melanie, his ex-lover's younger

sister, whom Norman desires but can't have. When Norman seems to drop

"d-e-a-d" of a heart attack after dinner, he's whisked first to Limbo -

where, Vidal says in the stage direction, "the acting style should be that

of perhaps the only entirely serious American play,

Hellzapoppin'." Then Norman goes to Hell, which means spending

eternity with Melanie (his unrequited adulterous love), plus the

occasional enema (people in Heaven love enemas).

But that's apparently a mistake, and soon Heaven is his destination,

white lights and all. That's where his trial takes place, with Jesus as an

onlooker and Grace as his judge. He's finally charged with the most

unforgivable crime - having lived - and the climax to his trial riffs on

Vidal's 1954 novel Messiah. When Norman learns that death is

"nothing" - literally, "no thing" - he says, "I hoped it would all add up

in some way." In the play's best line, Grace the Judge explains: "It added

up while there were things to be added up. Now the sum is finished."

The breezy dialogue in A Drawing Room Comedy takes parodic jabs

at government, religion, media, sexuality, marriage, religion, literature,

the elite, abortion, religion and much more. Small wonder it never got a

Broadway run. One character proclaims, "I love it when Arthur Miller

explains to us all the things that Harold Pinter doesn't." But another

prefers "the theater of vituperation, an evening of people insulting one

another, while all the time inquiring 'will you have another drink,'

occasionally varied by 'I'll mix my own.'" A Drawing Room Comedy

provides ample doses of both. We also get a brief passage mocking

heterosexual love and scolding society for its condemnation of - borrowing

a phrase - "the love that dare not speak its name." The dreamy prose of

Tennessee Williams also makes a cameo.

This all borders on camp, and it carries premonitory echoes of the

novels Duluth and Live from Golgotha, Vidal's later post-modern romps, or

"inventions" as he calls them. So this play may well have been an omen of

more widely received literary things to come.

An Evening with Richard Nixon And. . .

(1972)

Vidal's last contemporary political play was also his most short-lived: It

opened on April 30, 1972, at the Shubert Theater and closed 13

performances

later. But the play lives on in hardcover and paperback editions readily

available from antiquarian booksellers, and in a

33rpm recording of

excerpts issued by A&M Records. It also introduced Vidal to

a woman who would become a long-time friend: the actress Susan Sarandon,

who made her Broadway debut in the play. Almost 20 years later, Vidal

would portray an aging liberal senator in the movie Bob Roberts,

written and directed by Sarandon's husband, Tim Robbins.

An Evening with Richard Nixon And. . . - Vidal dropped the

And. . . of the title for the book publication - is a

hodgepodge of historical research that brings Nixon together with George

Washington, Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy, with guest

appearances by Adlai Steventon, Spiro T. Agnew, Gloria Steinem, Harry S

Truman, Helen Gahagan Douglas, Hubert H. Humphrey, Martha Mitchell, Nikita

Khrushchev, Lt. William Calley and many others, all of them interacting in

a broad satire on political corruption and American history. In the

commercially published book version of the play (from Random House), Vidal

used a different typeface to indicate lines of dialogue that the

characters actually said or wrote at one time or another in their lives.

He includes complete bibliographical citations at the end of the book for

Richard Nixon's authentic statements, presumably in case anyone tries to

accuse him of putting words into the Great Criminal's mouth.

Return to the Gore Vidal

Thumbnails introduction

Return to the Gore Vidal

Thumbnails introduction

If you came right to this thumbnail page and don't see a frame on the

left, please visit The Gore Vidal

Index now or after you've enjoyed the thumbnails, which you can access

from the main index page. And please send me comments if you have a thought, a suggestion

or a link to add to the index.

�Copyright 2005 by

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

kloman@pitt.edu

movie came to theaters in 1956 as The Catered Affair. Then he

adapted Nicholas Halasz's book I Accuse!, about the Dreyfus

trial, followed by adaptations of Tennessee Williams (Suddenly, Last

Summer) and Daphne du Maurier (The Scapegoat). In the late

1950s, he spent some time rewriting portions of the script for

Ben-Hur, injecting a subtle homosexual undercurrent in one scent

that, to this day, Charlton Heston denies exists. He wrote an original

screenplay about the Roman emperor Caligula in 1979 that

Penthouse publisher and "movie producer" Bob Guccione turned into

a high-class piece of pornography - which Vidal disowned. And in 1986, he

penned a well-received, four-hour television adaptation of Lucien

Truscott's military thriller Dress Gray.

movie came to theaters in 1956 as The Catered Affair. Then he

adapted Nicholas Halasz's book I Accuse!, about the Dreyfus

trial, followed by adaptations of Tennessee Williams (Suddenly, Last

Summer) and Daphne du Maurier (The Scapegoat). In the late

1950s, he spent some time rewriting portions of the script for

Ben-Hur, injecting a subtle homosexual undercurrent in one scent

that, to this day, Charlton Heston denies exists. He wrote an original

screenplay about the Roman emperor Caligula in 1979 that

Penthouse publisher and "movie producer" Bob Guccione turned into

a high-class piece of pornography - which Vidal disowned. And in 1986, he

penned a well-received, four-hour television adaptation of Lucien

Truscott's military thriller Dress Gray.

Gore Vidal became a playwright somewhat by accident. After the 1948

publication of his gay-themed novel The City and the Pillar,

major mainstream newspapers and magazines refused to review his subsequent

novels and so they

didn't sell very well. To supplement his income, he wrote five pulp novels

under three different

pseudonyms. He also turned to writing scripts for the emerging medium

of television, which had come to specialize in live drama and thus offered

satisfying work to serious writers like Vidal. This work lead him to write

screenplays for Hollywood films, and eventually to Broadway when one of

his live teleplays - the darkly humored science-fiction political satire

Visit to a Small Planet, so impressed critics and audiences that

a producer invited him to turn it into a theatrical play.

Gore Vidal became a playwright somewhat by accident. After the 1948

publication of his gay-themed novel The City and the Pillar,

major mainstream newspapers and magazines refused to review his subsequent

novels and so they

didn't sell very well. To supplement his income, he wrote five pulp novels

under three different

pseudonyms. He also turned to writing scripts for the emerging medium

of television, which had come to specialize in live drama and thus offered

satisfying work to serious writers like Vidal. This work lead him to write

screenplays for Hollywood films, and eventually to Broadway when one of

his live teleplays - the darkly humored science-fiction political satire

Visit to a Small Planet, so impressed critics and audiences that

a producer invited him to turn it into a theatrical play.

mountbankery, the plain showmanship, which is necessary to playwriting

inevitably strikes the novelist as disagreeably broad. Even the dialogue

is not the same in a novel as it is on the stage. Seldom can dialogue be

taken from a book and played by actors. The reason is one of pace rather

than of verisimilitude."

mountbankery, the plain showmanship, which is necessary to playwriting

inevitably strikes the novelist as disagreeably broad. Even the dialogue

is not the same in a novel as it is on the stage. Seldom can dialogue be

taken from a book and played by actors. The reason is one of pace rather

than of verisimilitude."

but almost certainly untrue material about Cantwell against him?

And who will the dying president endorse: the man he trusts, or the man he

thinks can win the election?

but almost certainly untrue material about Cantwell against him?

And who will the dying president endorse: the man he trusts, or the man he

thinks can win the election?