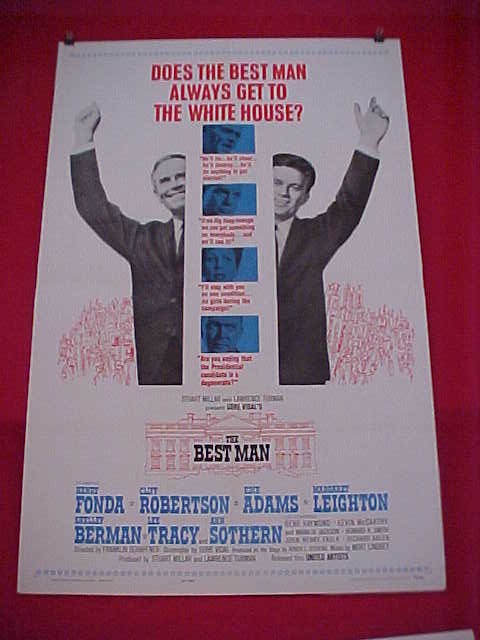

In November 1991, Gore Vidal came to Pittsburgh to shoot his scenes for the movie Bob Roberts: The Times Are Changing Back Again, a mock documentary about a right-wing businessman-cum-folk-singer who runs for a U.S. Senate seat in Pennsylvania.

The movie's writer/director/star, Tim Robbins, was the husband of the actress Susan Sarandon, with whom Vidal has been friends since Sarandon appeared in Vidal's 1973 Broadway play, An Evening with Richard Nixon. But even without the Sarandon connection, the role of Sen. Brickley Paiste - an old-fashioned liberal with supreme self-confidence - was perfect for Vidal, who has always called himself something resembling a liberal, but who is no less critical of liberalism than he is of any other political philosophy.

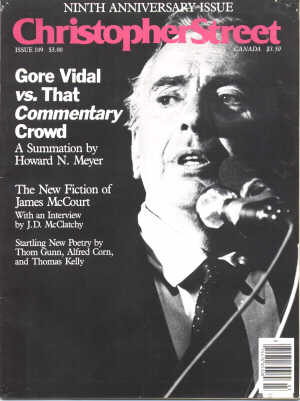

Vidal maintains that The System has failed the American ideal of democracy and freedom, and that the Democrats and the Republicans are merely different branches of one big political party, which he calls the Property Party (a borrowed term), with self-interest at their collective heart.

Vidal also claims that the art of the novel has withered in the past several decades. And he offers a most startling theory of what has gone wrong with the study of the novel in 20th Century America.

We had our conversation on the afternoon of Nov. 15, 1991, seated in the back of the auditorium of Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall in Pittsburgh. Vidal wore a three-piece suit and a bow tie, his costume for the movie. He had just finished filming a short scene and was waiting for a call to film his biggest scene - a debate between his character and the right-wing upstart. The debate would take place on the stage of the auditorium, where a production crew was busy setting up as we talked.

By the way, if you came directly to this page, please visit The Gore Vidal Index after you read the interview, which also appears in its entirety in Conversations with Gore Vidal (above), published in 2005 by the University Press of Mississippi.

KLOMAN: In 1956, you wrote about what the novel should be. You wrote that "it seeks the exploration of the inner world's distinctions and visions where no camera may follow, the private, the necessary pursuit of the whole, which makes the novel at its highest the humane art that Lawrence called the one bright book of life." What American novelists now do you think achieve what you spoke of a number of years ago as being the ideal for the novel?

VIDAL: Well, that piece went on to make the case that the novel was

pretty much finished - not as a form, but the audience had gone.

There

are more novelists in England than there are novel readers. I was

commenting then that film had taken over and was the preferred

artform

of this period, and that the novel has now joined poetry as something

well worth doing for its own sake, but it no longer has a great

public, it's no longer essential. The film director has taken the

place of the novelist.

VIDAL: Well, that piece went on to make the case that the novel was

pretty much finished - not as a form, but the audience had gone.

There

are more novelists in England than there are novel readers. I was

commenting then that film had taken over and was the preferred

artform

of this period, and that the novel has now joined poetry as something

well worth doing for its own sake, but it no longer has a great

public, it's no longer essential. The film director has taken the

place of the novelist.

I said to an interviewer not long ago, "You know, I used to be a famous novelist." He said, "Oh, well, you're still well-known. People read you." I said, "I'm not talking about me specifically. My category has vanished." Saying you're a very famous novelist is like saying you're a famous ceramicist - maybe a good ceramicist or a successful ceramicist, but famous? That was lost on our watch, Norman [Mailer] and I. So is the whole notion of the great writer who sort of spoke for his time.

KLOMAN: You say on "your watch..."

VIDAL: Well, during the period which Norman and I were principal players over the last 40 year - the war novelists, of which we were about the last. What good writing do I see? I don't see much of anything that I find terribly interesting. Like everybody else, I'd rather see a movie usually.

KLOMAN: Two of the best-selling literary novelists in America - that is, people who sell well but who also are considered to be literary figures - are Updike and Doctorow. Would you comment on them?

VIDAL: I don't really read them very much. I've read a book or two by each one. I think they write very well. There are obviously many different publics in the land. Updike has a sort of exurban New Yorker reading public, Doctorow more a city college intellectual. But I've never been very interested in either of them. The writers that interest me are a little bit more adventurous perhaps than they are. A woman in England now called Jeanette Winterton, a marvelous writer. I find someone like Golding interesting. I introduced Calvino to the American public about 15 years ago. That's what interests me. I don't care so much about naturalistic novel writing. It's had its day.

KLOMAN: Do you believe that your novels achieve what the novel should be?

VIDAL: Well, some do and some don't. It depends on what I'm doing. I do two kinds of books: I reflect upon history and religion; and I have my total inventions, like Duluth and Myra Breckinridge, and those alternative worlds, comic and satiric, whatever word you want to use, the reverse of realism. Actually, I've been what they call an experimental novelist, probably the most varied of the lot. But as nobody knows what anybody has written - nobody knows. [Chuckles]

KLOMAN: Is there one or two of those books you're most fond of?

VIDAL: I like Duluth, and certainly Myra and Myron.

KLOMAN: Messiah?

VIDAL: Messiah, yes. It's an interesting book. Certain of them have become cults. Messiah is a cult book, Kalki is. Duluth never really caught on because nobody knows about it. Perhaps they'll find out. There's no longer a grapevine for books. In the old days somebody would read a book and tell somebody else about it. It would be word of mouth. That's just sort of stopped. We don't really have any critics that people pay attention to. In the old days, someone like Orville Prescott in the daily New York Times could make or break a book.

KLOMAN: Why has this happened?

VIDAL: Lack of interest.

KLOMAN: What creates that lack of interest?

VIDAL: Two generations have now grown up on television. They don't learn to read very well, if at all. If you don't enjoy reading by the time you're 13 or 14, you're not going to pick it up. And they watch television from babyhood, as a sort of pacifier. I think that a mind shaped by flashing images works differently than a mind that has been shaped by linear type. Don't ask me what the difference is because I haven't a clue, because I belong to one side and they're on another side.

KLOMAN: Is there any irony that you do films?

VIDAL: No, no. I do everything, whatever amuses me. Narration is all the same. The big question: Are the movies an artform? That's a hard one. The result sometimes looks like it, but it's such a collective enterprise, you can't really say where the authorship is, which is where the Cahiers du Cinema people lept right off the edge, particularly with those cornball Hollywood directors of the '30 and '40s whom they began to call masters. They were just sausage-makers turning out what the studio told them to do.

KLOMAN: You wrote in 1966 that "in a civilized society, law should not function at all in the area of sex, except to protect people from being interfered with against their will." You included prostitution on the list. In 1991, we feel we're more enlightend about prostitution, we know what leads so many women to prostitution. Any thoughts on that?

VIDAL: Well, men too. Prostitution is a great

necessity, and

should....

VIDAL: Well, men too. Prostitution is a great

necessity, and

should....

KLOMAN: But sociology points to the fact that so many prostitutes were abused or sexually molested...

VIDAL: ...So many wives, too. Prostitution is a natural thing, and in a world made more dangerous with AIDS, [we need] legalized prostitution with medical examinations, which is pretty much what they did in the l9th Century. 1948 was the terrible year. A French Communist senator - a lady - and an Italian communist senator - a lady - each of them in '48 passed laws banning prostitution. They had houses and they were legally and medically inspected at regular intervals. Then of course all the women ended up on the street, and they had a huge epidemic of venereal disease, which was a disaster. Misplaced morality.

KLOMAN: Politics. When the Kennedy presidency began, you said that "civilizations are seldom granted a second chance," and you somewhat looked fondly upon the Kennedy administration as a second chance. But in '67 you said, "something mysteriously went wrong" with the presidency. Might he have become a great president in a second term with more experience? What was it that went wrong?

VIDAL: That's what he told me. [Chuckles] He didn't have it. He had no plan. He was playing a game. He enjoyed the game of politics, like most of them do. There was no real substance to him. He was quite intelligent, very shrewd about people, but he liked the glamour of it all. He loved war, he had a very gung-ho attitude. I began to part company with him about the Bay of Pigs. Then we all forgave him, and he started the invasion and started to beef up the troops in Vietnam.

KLOMAN: Was the Bay of Pigs naivete?

VIDAL: Well, it was pretty dumb. He could easily have said no. The intelligence was so dreadful. Of course he was then blamed by the CIA for not using aerial backup, but then it was pretty clear that we'd made an error. They convinced themselves that the Cubans were going to rise up against Castro.

KLOMAN: How much of your assessment of him do you think he would agree with himself? Was he aware of his lack of substance or depth? Did he think he was a great man?

VIDAL: He thought himself a pretty good man. He wasn't at all vain, I

mean no more than the average man. His line to me was that a so-called

great president is entirely happenstance, the period you happen to

be

living in, and all the great presidents have always been living in

disastrous times, like Reagan. In other words you have to have war.

It's the war presidents that people remember, not the ones in

between.

And I think he designed the uniform for the Green Berets himself. I

saw him drawing it, and I said to him, "Do you know the last Chief of

State who designed a military uniform was Frederick the Great of

Prussia?" [Chuckles] He was not terribly amused by the comparison.

[Laughs]

VIDAL: He thought himself a pretty good man. He wasn't at all vain, I

mean no more than the average man. His line to me was that a so-called

great president is entirely happenstance, the period you happen to

be

living in, and all the great presidents have always been living in

disastrous times, like Reagan. In other words you have to have war.

It's the war presidents that people remember, not the ones in

between.

And I think he designed the uniform for the Green Berets himself. I

saw him drawing it, and I said to him, "Do you know the last Chief of

State who designed a military uniform was Frederick the Great of

Prussia?" [Chuckles] He was not terribly amused by the comparison.

[Laughs]

KLOMAN: Vietnam would not have been different had Kennedy lived until 1968?

VIDAL: Nah. I think he might have just played right along. They got themselves into so much false thinking - the "Dominos," if Vietnam falls, Thailand falls. But it doesn't fall. [Chuckles] But they get these mindsets, then nothing they do makes any sense. "We fought the war to contain China." I mean, what's he talking about? If you want to contain China - I knew enough history and geography, which he didn't, and nobody in the administration did - the Vietnamese had been for thousands of years dedicated enemies of the Chinese. If you want to contain China, you help Ho Chi Min - you don't drop bombs on him. I used to go on television and argue with the administration people - this is after Jack was dead.

KLOMAN: What kind of president would Bobby Kennedy have been?

VIDAL: Pretty sinister. A little Machiavellian. Not Machiavellian, he was Savonarola, he was highly moral, obsessed, vengeance. Jack had a funny story about him. Nobody could stand him, they put up with him because of John. And somebody came up to Jack and was complaining about Bobby's behavior. And Jack says [slipping into a hauntingly good Kennedy impersonation]: "Look, you've got to remember, Bobby's a policeman, he's gotta arrest somebody. If he hasn't arrested somebody, he'll go home at night and he'll arrest Rose." [Laughs]

KLOMAN: In 1968, you wrote about liberalism: "Trying to make things better, trying to compromise extremes, trying to keep what he have from falling apart, the liberal goes about his dogged task." Who are the great liberals today, who can we look to to make things better? Who can the Democrats look to next Year?

VIDAL: Well, I think since I wrote that, the system has collapsed. What is wrong is systemic. A change in personnel is not going to make the slightest difference. No matter who's going to be elected president, the situation is going to get worse. The Constitution has ceased to function. It's totally corrupt. The elections now cost the world. Whoever's elected president will not represent the people of the country, he'll represent the interests who gave him the money to run. Why do you think Bush can run on cutting the capital gains tax? That's the price of having the office bought for him.

KLOMAN: There's no chance for a true populist?

KLOMAN: There's no chance for a true populist?

VIDAL: None. None. Even if he could find the money, which is quite doubtful, billions of dollars would be dedicated to destroying him. They wouldn't allow such a thing to happen. The two parties are the same, and some people pay for both. The decisions are made in the corporate boardrooms, not only in the U.S., but in Tokyo as well. We don't have representative government. Congress has given up. The only two powers it has - one is to declare war, the other is the power of the purse, the budget - it has given up both. So the Congress has ceased. Watching Clarence Thomas being coached by the White House, one realized that this Supreme Court has nine mediocre lawyers acting as a legal council to the executive. They're there to scream "hosanna," right on, at any executive decree. So where are the checks and balances, where's the government? We have a national security state, and the country's run by the national security council and is not accountable to anybody. Ollie North is still at large.

KLOMAN: How do they get away with it? Surely the people must be somewhat complicitous in this?

VIDAL: The people don't know anything about it. Only about 10 percent are interested in politics at any time. In bad times, people get interested because they want to know why they don't have any money.

KLOMAN: But if only 10 percent are interested, then the other 90% are complicitous for not being interested.

VIDAL: They have no control. People aren't stupid. They're ignorant - we have the least well-educated population of any First World country. We're at the bottom of every single list for reading skills and mathematics. We have no public education, so you start right off - they don't have much information. Half of them never read a newspaper - just as well, looking at them - half of them don't vote for president. But they understand the system. They know it's corrupt. Every poll you take, Congress is way down there among people you admire. They're not admired. Everybody knows it's a corrupt game. What we need, a way out, is a constitutional convention. We can start this thing over again. Liberals immediately start screaming, "They'll take the Bill of Rights away." Well, the point is, they're taking it away anyway, the Supreme Court. If they're really going to do that, the famous "they," why not do it in an open convention, see where you stand. Jefferson wanted to have a constitutional convention every 30 years. "Nobody should expect a man to wear a boy's jacket," he said. Nobody dreamed this document would still be sitting around 200 years later with all its patches.

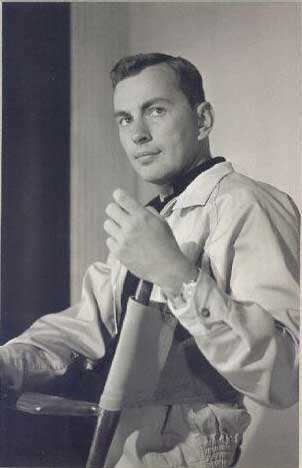

KLOMAN: You open Messiah with the words, "I envy those chroniclers who assert with reckless but sincere abandon: I was there, I saw it happen, it happened thus." It goes on to say that "we are all betrayed by those eyes of memory, the vision altering, as it so often does, from near in youth to far in age." You were not yet 30 when you wrote that. You're, well, older than that now. I wonder, is that true of you? How has your vision altered from youth to advanced youth.

VIDAL: Hmmm, to old age. I remain the same. The wisdom in that passage is that what alters is memory, that the way you remember things changes as you get older. Some things you remember more clearly, and some things you start to forget

KLOMAN: Some of your memories, as you're talking now, seem very vivid. Gene Luther in the book says, "Something has happened to my memory." What do you find yourself forgetting, or wondering if you can trust to memory?

VIDAL: Well, I'm now at the point where I'm the subject of a number of biographies.

KLOMAN: Authorized?

KLOMAN: Authorized?

VIDAL: There's one that is, Walter Clements at Newsweek is writing it, he's been at it five years now. So I am obliged to think about the past. My memory of almost anything is not the other person's memory, it's totally different. And you get really to the point: What do you trust? I'm supposed to have invented something called "historicity," and I'm going up to Dartmouth for a Gore Vidal week starting Monday. They've got about six professors from around the country, and there's a whole theory which they call "historicity," which I represent, which is the intersection between fact and fancy exemplified by my books about the American republic. I'll know more about what it is when I get there. I'm not a literary theoretician. It really is a relativeness, it's Heisenberg's law applied to history. Heisenberg's principle is that nothing "is," but it only "is" in relation to where you're standing to see. There is no actual thing there, there's just a variant view of it one has.

KLOMAN: You're standing farther away from the things you once saw. How do you find your vision of the things you know you've seen alter?

VIDAL: Well, the mind is always kind of a machine. The mind doesn't remember anything, it remembers what it last remembered. It's like an onion, there's just layer after layer. If you've had a long life, you remember quite a lot.

KLOMAN: Do you ever read the books you wrote in the '40s and '50s? I wonder how you see them or think of them now.

VIDAL: No. I read about them because they do these Ph.D. things and sometimes I look at them, I don't really read them. It comes back to me, the books, when I read what they're writing about.

KLOMAN: Do you find there's a lot of scholarly interest in your work now?

VIDAL: Oh, yes.

KLOMAN: Why?

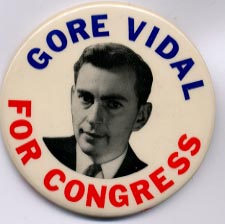

VIDAL: Well, I was blacked out for 40 years by the American universities and by the press.

KLOMAN: Why?

VIDAL: Oh, too numerous, the reasons. And they suddenly realized that they had been putting on Hamlet without the Prince, and you can't go on doing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern forever. And it just suddenly hit them. And I didn't much care for the universities. I don't like the bureaucratization of literature which goes on there, or history. So I've been sharply critical of them. Now they realize the game is over, there are no longer voluntary readers, very few of them, dying out. And the universities want to at least keep some part of literary culture alive - usually the wrong parts, since they have no ability in telling what's what. So I went to Harvard this spring and gave the Massey lectures. Now I do the week at Dartmouth, they'll show two films of mine, do a play. And then the seminar in historicity and so on. Papers will be read, it should be interesting

KLOMAN: Some people might say - but I would never ever say this - that to hear you say they've been doing Hamlet without the Prince - that sounds as little, what's the word, egotistical?

VIDAL: Sure it is. But it's pretty clear to me that there's a big hole in the middle, and if it isn't me, what is it? Why is there a hole there? What they do is they want people who celebrate received opinion. And this is a very, very conservative country intellectually, very meager, to be blunt. So they want very safe, everyday sort of writers. They have experimental writing, but it has to look like somebody has studied Finnegans Wake very carefully and is going to try to recreate another sacred masterpiece. I think [Joyce] wrote to be read, not as much to be taught. You have two generations now that are writing books within the universities to be taught within the universities.

KLOMAN: It seems that if there are no voluntary readers, then you must write to be taught.

VIDAL: I wouldn't know how to do that, and I wouldn't do it if I could do it. But that seems to be the canon.

KLOMAN: Your story A Moment of Green Laurel is about an adult who essentially encounters himself as a child. It's nostalgic, melancholic...

VIDAL: It's also ripped off by Rod Serling.

KLOMAN: For a Twilight Zone?

VIDAL: Yes.

KLOMAN: Did you know him?

VIDAL: Yes. I told him, too. [Chuckles]

KLOMAN: Did he admit it?

VIDAL: No.

KLOMAN: I wonder how often you look back, consider the past, relive the past, as that protagonist does in the story?

VIDAL: There's flashes occasionally - of memory.

KLOMAN: What sort of things do you flash on when you have flashes like that of the past? Perhaps mystical, melancholy flashes?

VIDAL: Oh, I don't do much memory lane. It's just that a place, perhaps, will trigger the imagination and memory. I don't traffic much in the past. But as I said, it's on my mind now because I have to answer all these questions.

KLOMAN: A theme that has run through your work is the final line of Washington, D.C., where you write: "Change is the nature of life, and its hope." Can you tell me some of the changes you've seen yourself go through in your public and private life?

VIDAL: I seem to be a rather monotonous figure. I don't think I change much at all. Change is going on all the time. We can't control change.

KLOMAN: But individual change, personal change? Does that statement not apply to the individual as well?

VIDAL: That line applies to the human race, the species actually, species and adaptation. That's what I had in mind there, not the individual changing. People do - from what to what, since you don't know what you started out as? Where's the measuring stick?

KLOMAN: What was the impetus to write Messiah? It's almost 40 years old, and it seems more relevant today than ever. Bob Roberts is about, in part, what Messiah is about.

VIDAL: It's the same story, in a sense.

KLOMAN: Did others see the media-ization of public figures at that time like you did?

VIDAL: It did so badly. Nothing of mine would be reviewed in the daily Times, or Time or Newsweek. Five books were just blacked out, so I had to go to television.

KLOMAN: Not reviewed at all? Why?

VIDAL: After The City and the Pillar, Orville Prescott of The New York Times told Nicholas Wreden of E.P. Dutton that he would never read, much less review a book of mine. So that meant the daily New York Times - he did all the daily reviews. Time magazine and Newsweek followed suit. So I was blacked out by the Times, my least favorite newspaper. Oh, they poisoned a lot of wells. Just as recently, when my Lincoln was being done on NBC, the "dreaded" William Safire, author of Freedom, a book about Lincoln which did quite badly, got them to write a piece about the mini-series, trying to kill it before it was shown: It was full of errors, the historians didn't like it, and so forth and so on. It was pure New York Times poison. They do it all time. They just did it to poor Norman, getting John Simon to review him, knowing that John Simon would give him a venomous review, which is what John Simon exists for.

KLOMAN: When you say poor Norman, are you being ironic, or do you really feel bad for him?

VIDAL: Oh, I feel for him, I do. I have a certain fellow feeling for Norman.

KLOMAN: The idea that you put forth in Messiah is what Bob Roberts is about, and now we're beginning to realize it. We certainly began to realize it with the 1960 presidential elections...

VIDAL: ...As they say, "ahead of its time." A lot of people have tried to make movies of it over the years. A lot of scripts were written.

KLOMAN: Seriously? Anybody of note or significance?

VIDAL: Well, the guy, what's his name, the guy who produced Hair, Michael Butler. He tried five, six years ago for a film or a play.

KLOMAN: I always wondered who would play John Cave in the film. I've also had some wonderful casting in mind for a film of Washington, D.C. I've always imagined Paul Newman as Blaise Sanford and Burt Lancaster as Burden Day.

VIDAL: That would be nice. Someone just bought Empire. We're trying to get him to do the whole lot.

KLOMAN: How common, in the early '50s, was the idea of people being sold by the camera, what Messiah and Bob Roberts are all about.

VIDAL: It hadn't started really. Television was very new. The first sort of TV campaign was '52, Eisenhower vs. Adlai Stevenson.

KLOMAN: Was that in any way an impetus for Messiah.

VIDAL: It might have been. Adlai Stevenson was an unknown governor of Illinois but had been picked by Harry Truman to be the nominee. And Stevenson, unknown, got up and made a speech at the convention welcoming the delegates, and he was famous for a night, the whole country knew him. And I thought, "This is new." That was about the time I turned my attention to Messiah.

KLOMAN: When you wrote The City and the Pillar, what consequences did you expect to face after its publication? I believe I read once that you said it ended your chance for a political career.

VIDAL: Well, it did at that time. But I picked it up again in 1960 and then in '64. I had the election to the House but turned it down because I wanted to go back to novel writing. I knew it [The City and the Pillar] was going to cause a lot of distress...

KLOMAN: What sort of distress?

VIDAL: Well, for the press and so on

KLOMAN: For friends and family?

VIDAL: Oh, that's their business. Some interviewer for a magazine asked my father - very clever interviewer, they usually aren't that enterprising - she said to him, he was a charming man: "Don't you find Gore terribly courageous for the positions he takes?" He said, "Well, what's courageous when you don't care what people think about you?" [chuckles] It was a rather good take on it.

KLOMAN: Were there any personal consequences among friends and family?

VIDAL: Nnnn.

KLOMAN: Peers? Other writers?

VIDAL: No, no. I think they were delighted. I was the leading war novelist, and suddenly I was eliminated. I was no longer competition to any of them. [Chuckles]

KLOMAN: The book is not very sexually explicit, whereas of course Myra makes up for lost time. Was that because of the times? Did you feel restricted from writing explicit sex in the book? Certainly in '68 you didn't.

VIDAL: No, in '48 is was pretty explicit.

KLOMAN: By today's standards...

VIDAL: ...oh, it's mild, yeah...

KLOMAN: But by the standards of the time...

VIDAL: ...oh, it was pretty far out, yeah.

KLOMAN: Did you want to go farther? Did you want to describe more?

VIDAL: No, I'd done quite enough.

KLOMAN: Did you ever consider a sequel to the character in the book?

VIDAL: He crops up again, Jim Willard, in The Judgment of Paris. It was all invented you know. I wanted to make this thing look like a very all-American, middle-class, Norman Rockwell boy to give it its force. Some brilliant type wouldn't have worked.

KLOMAN: In the '90s, one of the big issues of the gay rights movement is outing. Any thoughts on that?

VIDAL: Well, the theory is okay. But you have to go back to what my positions are, which is that there's no such thing as a "homosexual" person and no such thing as a "heterosexual" person. These are adjectives which describe actions. They never describe a person. So I start out by denying that these two categories exist. Well, to say that to the average American, they just can't get that through their heads, no matter what their interest might be. So once you take that, then of course I'm all for changing laws and removing persecution and so on, but not ever in admitting that there is such a thing. I mean, only a society as sick as the United States would come up with these categories.

Behind it is this really very, very primitive society - you asked about the reaction to The City and the Pillar - I hadn't realized to this extent that there really was no civilization here at all. We have brilliant people every now and then, but there is no intellectual world, for instance. The nearest thing was the sort of Jewish group in New York to which I belonged - The Partisan Review, now The New York Review of Books - but it's so small. It's basically rather incoherent.

KLOMAN: So the responses of intellectuals to some of these issues...

VIDAL: ...Well, they were just as bad as my Baptist cousins in Mississippi. From intellectuals I would have expected more intelligence, but then you realize there isn't much intelligence. I always thought I would live long enough to see some sort of civilization take root in the U.S. I did my bit, but it's rather worse than it was.

KLOMAN: The women's movement has made some progress, the civil rights movement has made progress. The gay rights movement seems not to be makinq as much progress...

VIDAL: ...Well, AIDS put a big cramp into that, of course. It's helped demonize it all over again.

KLOMAN: Will it ever happen that the gay rights movement will make the advances that women's rights and civil rights have made?

VIDAL: Oh, sure.

KLOMAN: How long will it take?

VIDAL: Who knows, who knows. I'm all for militant action and changing the laws.

KLOMAN: How militant? Some see outing as militant. Revealing people in positions of influence?

VIDAL: Yeah, but you know, a man is married, he has four children, and occasionally he goes out with a Boy Scout. But what is he? He's a married man, he's a father, he's bisexual like everybody else. What's the big deal? It's of no interest at all what anybody does, nor should it be of any interest. It carries no moral weight.

KLOMAN: But it does for so many people.

VIDAL: Well, it does because they don't understand morality and they haven't got anything else going on in their head. I would say that certainly I would be in favor of outing a judge coming down hard on the rights of quote-homosexuals-unquote if he were discovered in a compromising position - why, yes, he should certainly be exposed.

KLOMAN: Actors and actresses?

VIDAL: Why bother with them? They're not doing any harm. Rock Hudson was very funny about that. He was in some faggot bar in San Francisco - I knew him slightly for years, a nice guy - and a journalist said to him, "Aren't you worried about appearing at a place like this?" This was 20 years ago. And he said, "No, why should I be?" The guy said, "Yeah, but they'll write about you - you're queer." He said, "Try. The American people will not face the fact that I'm queer." And the journalist said, "Okay, may I write a story and try to sell it to Confidential or something?" He said, "Go ahead. They won't take it." And the guy went ahead and did it, I read about it somewhere. But it was out of bounds, it was just not going to be considered, it couldn't be considered.

KLOMAN: When you were writing Myra Breckinridge, did you realize - I don't know, "shock" is such a hard word, but it was certainly different from anything you'd written before it. Did you realize people would raise a few eyebrows at it? Were you laughing while you were writing it?

VIDAL: Oh, I thought it very funny, extremely good for the folks.

KLOMAN: "The folks?"

VIDAL [wryly]: The folks.

KLOMAN: The ones who liked Washington, D.C. so much?

VIDAL: And Julian, yes. They may not have liked [Myra] all that much, [chuckles] but I though it was funny.

KLOMAN: What was the impetus for that book?

VIDAL: I just heard a voice.

KLOMAN: What did the voice say?

VIDAL: "I am Myra Breckinridge, whom no man will possess." I didn't even know she'd had a sex change until I was almost half way through.

KLOMAN: Seriously?

VIDAL: Yeah. I had no idea. It came out of the ba-loo.

KLOMAN: The British edition of the paperback says this: "Wanting in every way to adapt to the high moral climate that currently envelopes the British Isles, the author has allowed certain excisions to be made in the American text." Was that true? Did you participate in the excising. Or did you just allow them to be made?

VIDAL: Yeah. Then about 10 years later, I put it out again with all that had been removed.

KLOMAN: I once compared Chapter 29 to see what they took out. Just a few details and references to anal penetration and stuff like that, literally just three or four words. What's this "high moral climate" that enveloped the British Isles in the 1970s?

VIDAL: [Chuckles] I forget what that was.

KLOMAN: What happened to Myra? What went wrong with the film?

VIDAL: One of the worst directors probably in the world was assigned to it.

KLOMAN: When it began, did you have hopes of it turning out?

VIDAL: Yes! Mike Nichols wanted to do it. All we had to do was wait for him to finish Catch-22, and he would have gone on to do that. He wanted Anne Bancroft as Myra.

KLOMAN: Anne Bancroft was interested in Myra! And they wouldn't wait? Imagine how film history would have been changed - or something like that.

I'd like to do a few quick takes on some people you've known over the years. Just say a few things about them. Norman Mailer.

VIDAL: Mmmm. No, we don't do that.

KLOMAN: Truman Capote?

VIDAL: No quick takes.

KLOMAN: No quick takes? Paul Newman?

VIDAL: Old friend.

KLOMAN: Guccione?

VIDAL: Nothing to say.

KLOMAN: Richard Nixon? Surely you have something to say about Richard Nixon.

VIDAL: (yawning, stretching) I did, in An Evening with Richard Nixon, in which appeared in 1972 an actress called Susan Sarandon, which is why I'm here now.

KLOMAN: You live mostly, where, in Italy?

VIDAL: In L.A.

KLOMAN: How much of the year in Italy?

VIDAL: Every year is different.

KLOMAN: What will your next novel be.

VIDAL: Live from Golgotha.

KLOMAN: What's it about?

VIDAL: Well, NBC is trying to restore its ratings. They get a team back to Golgotha to make a special about the Crucifixion. Now, who's going to be on that cross? Everybody thinks that Shirley MacLaine is channeling in and a cyberpunk is at work and the memory banks of Christianity are being eliminated. Only one person can tell the story, that's Timothy, a friend of St. Paul, and he'll act also as anchor at the Crucifixion. That gives you a little idea. A story of worn faith.

�Copyright 2005 by

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

kloman@pitt.edu