| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |review |

|

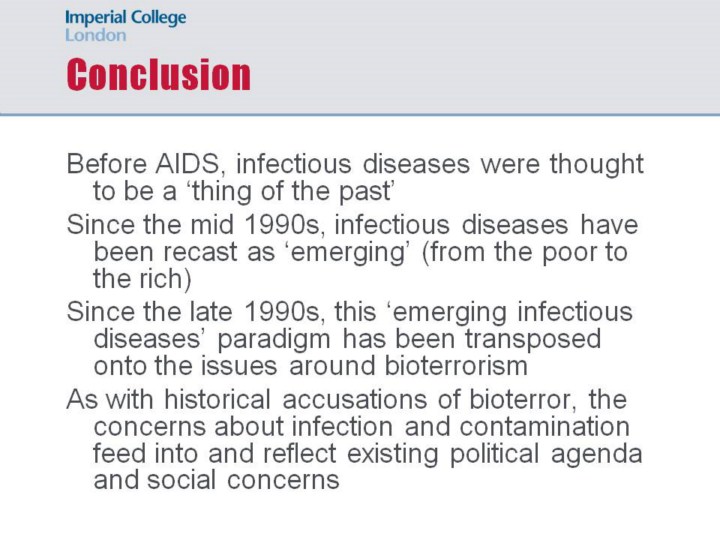

The issue of bioterror illustrates how the emerging infectious diseases worldview had become established to the extent that it became the ‘natural’ frame of reference to conceptualize the threat of bioterrorism. The blaming discourse around emerging infectious diseases, based on the antimony of the healthy self and the diseased other, is transposed onto the bioterrorism discourse, as are the militarized metaphors used to describe infectious disease – infections, invasions, terrorist ‘cells’, detection, defence, eradication and so on. The potential bioterrorist, like the infected other, threatens both individual citizens and the body politic from within or without. The response in both cases is to limit migration and to increase border security, and to introduce draconian legislation to limit civil freedoms in the name of public health and internal security. In other words, the 21st century response to the threat both of the infected other and of the bioterrorist is to revert to a more primitive group instinct: to regard outsiders with suspicion and fear and to seek to exclude them.

Bioterrorism provides a stunning exemplar of how much infectious disease had become politicized at the end of the 20th century. The threat of bioterrorism was cultivated into mythic status for over ten years. When the anthrax letter attacks ‘proved’ that the threat was ‘real’, the hawks in the US government then used the myth of bioterrorism to justify the war against Iraq. But many scientists and public health officials also colluded in the fantasy, hoping that spending on biopreparedness would prove ‘dual use’ and serve their aims, which was to redirect funding to woefully neglected public health. Eventually it became clear that bioterrorism was diverting money and talent away from US public health, rather than directing resources towards it. |