XIII. The Formation of the United States Steel Corporation

After the formation of Federal Steel in 1898, competition among the large steelmakers became even more intense. In the mid-1890s, Andrew Carnegie had pioneered the development of the truly integrated steel mill in Pittsburgh by absorbing ore properties in the Mesabi Range in Minnesota, causing other steelmakers like Illinois Steel to follow suit. The merger of several steel properties into the $80 million National Tube Company in 1899, also financed by J.P. Morgan, demonstrated that the large steelmakers were beginning to focus their integration efforts on absorption of the fabrication industries. The inclusion of the Johnson Company in the Federal Steel merger the year before had been an indication that once ore stocks were secured, steel mergers would target companies with established markets in finished steel products.

Carnegie decided to take on the Morgan-backed steel companies directly by planning the construction of his own major tube plant at Conneaut, Ohio. Fearing the outbreak of crippling competition among the big steel producers, Morgan discretely approached Charles Schwab, the chief executive officer at Carnegie Steel in Pittsburgh, about the prospect of purchasing all of Carnegie's steel holdings. In early 1901, Carnegie offered to sell for $480 million and Morgan agreed. With the Carnegie properties in hand, Morgan and Gary were then able to plan the consolidation of a wide range of steel industries by the formation of a huge holding company, the United States Steel Corporation. Included in the 1901 merger were three of the country's largest steelmakers, Carnegie Steel, Federal Steel, and National Steel, each of which had been the product of the merger of established steel making and finishing operations. Also included were six large fabricating companies.

The role of Tom Johnson in the Federal Steel merger is not entirely clear. According to accounts of the principals, he was approached by Morgan in the summer of 1898 about the possible inclusion of the Johnson Company in the Federal Steel merger. Johnson had for years maintained a very high profile in New York financial markets acting as a financial advisor and broker for both Pierre and Coleman du Pont. He certainly would have been far better known to either Morgan or Gary than Arthur Moxham, who had always counted on Johnson, R.T. Wilson, Pierre du Pont, or his brother Edgar (who had established a mining, construction and contracting business in New York) to navigate the credit market for him. After the Federal Steel merger in 1898, Pierre du Pont, again on the advice of Tom Johnson, formed an investment syndicate with seven of his brothers, sisters and cousins through the New York firm of Flower & Company and invested heavily in Federal Steel stock. The syndicate held up to $250,000 in Federal securities and realized a handsome return on its investments when the U.S. Steel merger was completed.

After successfully negotiating and financing the Federal Steel merger

in September 1898, Elbert Gary was persuaded by Morgan to retire from his

private law practice and assume the Presidency of Federal Steel. Shortly

thereafter he approached Tom Johnson in an attempt to interest Coleman

du Pont in accepting the Presidency of Lorain Steel. But Coleman did not

want to commit himself to the Lorain enterprise and instead focused his

energies on his growing portfolio of speculative street railway investments.

He remained in Johnstown until mid-1899, continuing as general manager

of the Johnson Company mill during the transfer of its assets to Federal

Steel. During that time, he also initiated negotiations for his own takeover

of the Johnstown Passenger Railway Company, which local interests had bought

from Tom Johnson only a few years before. In the fall of 1899, he returned

to Louisville where he again was involved in overseeing his father's coal

and iron mining companies. By 1901, he had completed his purchase of the

street railway in Johnstown and asked his younger brother Evan, who had

yet to find his business niche after seven years in Johnstown, to manager

the railway for him. Evan would ultimately rise to General Manager of the

railway, a position he held until his death in 1941.

XIV. The Apprenticeship of Pierre S. du Pont

With the death of family patriarch Eugene du Pont, the Du Pont Company in Wilmington floundered for direction. Into the vacuum moved Coleman du Pont who, with his cousins Pierre and Alfred I. du Pont, purchased controlling interest in the company in 1902. The planning of the takeover was financially intricate, and bore distinct similarities to the manner in which their old mentor Tom Johnson had financed the takeovers of various street railway companies twenty years before.

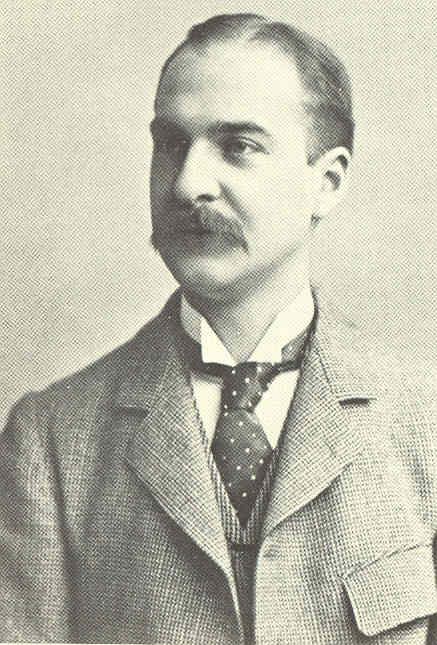

While the Federal Steel merger had involved the sale of all of the Johnson Company's mill, coal, and railroad assets, Tom Johnson had held back his land development and street railway interests in Lorain hoping they would appreciate in value after Federal Steel invested its own capital in the expansion of the Lorain mill. To supervise those interests, which still operated under the Johnson Company name, Johnson called upon young Pierre du Pont. At the age of twenty-eight, Pierre, like many of the younger men in the du Pont family, was languishing impatiently below the executive level in the Du Pont Company in Wilmington. Anxious to break out on his own and perhaps to oversee the sizable investments he still had in the company, he accepted the Presidency of the Johnson Company.

For three years Pierre supervised Tom Johnson's land development and railway investments in Lorain. The experience became his apprenticeship in financial management and business organization. He consulted continuously with both Johnson (in Cleveland) and Moxham (who by now had moved to Nova Scotia) on how to further develop the residential, commercial and industrial properties around Lorain and developed an understanding of the technical and financial intricacies of managing a street railway.

But after a year of apprenticeship, management of the Johnson Company operations in Lorain had become quite routine and Pierre wanted to venture out by investing and managing his own street railway. With the expert counsel of both Johnson and his cousin Coleman du Pont, he put together the necessary capital and purchased the street railway in Dallas, Texas in June 1901. Pierre spent a great deal of time in Dallas over the next year, and improved the railway's capital worth to the point that he could sell it for a modest profit in August 1902. He then returned to Wilmington to join Coleman and Alfred du Pont in the purchase and reorganization of the family company.

XV. Moxham the Steelmaker and Corporate Strategist

After the sale of the Johnson Company to Federal Steel, Arthur Moxham was financially quite comfortable and retired at the age of forty-four to embark from London on a cruise around the world on his yacht the S. Y. Erl King. Included in the party were his wife and four children, and his wife's parents Thomas Cooper and Dulcenia Coleman. As might have been expected of the Welsh ironmaster, his retirement lasted only a few months. When he docked in New York in the early autumn of 1899, Moxham was approached by a close business associate H. M. Whitney of the West End Street Railway in Boston. Whitney had arranged for the construction of a major steel facility with the aid of the Canadian government on the eastern coast of Nova Scotia and offered Moxham the Vice Presidency and General Managership of the new mill. Before accepting, Moxham arranged for his brother Edgar, a mining engineer of some considerable skill and experience, to investigate the quality of coal, iron ore and limestone deposits of the Sydney region and to report on any construction or production difficulties that might be anticipated. Edgar's extensive report was completed by November 1899 and Moxham accepted the challenge of building the steelworks of Dominion Iron and Steel Company.

The large integrated $15 million steel works was the first modern blast-furnace and open hearth plant in Canada. Located at Cape Breton, the mill took advantage of the Sydney coal and limestone fields and the ore deposits in nearby Wabana in Newfoundland. The transshipment of these raw materials and the pig iron and finished steel products ultimately produced by the mill was facilitated by its location right on the harbor at Sydney. Construction of the blast furnaces and blooming mills began in late November of 1899 and Moxham built a majestic home for himself across the harbor. He commuted to the mill each day by steam launch.

It was to be a bitter three years for Moxham and his family in Sydney. Impurities in local iron ore made production of pig iron difficult from the outset. High sulphur and ash content of local coal caused the blast and open hearth furnaces to burn with excessive temperatures and required frequent and costly relining. His cautious Board of Directors constantly questioned his high production costs and resisted his efforts to overcome technical problems in the manner of his previous success with the Johnson Company -- through increased capitalization. Because of these technical problems, Moxham was not able to make quality steel at the Dominion mill until January 1902. Lack of capital prevented the roll mill from being completed until 1904.

The absence of skilled workers in isolated Nova Scotia also meant that Moxham had to fill most of the skilled positions by recruiting men from mills in the States. Several men joined him from the Johnstown and Birmingham operations, but turnover at all levels was extremely high. Both of his sons, Tom and Egbert, apprenticed at the mill, in the same manner that Moxham himself had apprenticed at the Louisville Rolling Mill thirty years before. Tragically, his eldest son Tom, a plant foreman and only twenty-five years of age, was killed on June 5, 1901 while supervising the loading of rail cars at the mill. Tom's young wife Ellen, expecting their first child, decided to remain in Sydney until after the birth. But two months later, Ellen died after her child was stillborn. All three were taken by train to Louisville for burial in Cave Hill Cemetery.

By family accounts, the deaths of their son Tom, daughter-in-law Ellen and first grandchild drained the spirit from Arthur and Helen Moxham. The Nova Scotia experience had involved Moxham less in the metallurgical experimentation he truly loved and more in the kinds of board room haggling over finances that he had come to loathe in Lorain. Moreover, it had taken his son Tom who he had seen as the natural heir to his interests in steel making. In the summer of 1902, financial control of both the Sydney Coal Company and Dominion Iron and Steel passed from Whitney to James Ross, the founder of the Canadian Northern Railroad. Moxham resigned from Dominion and returned to Great Neck, Long Island, where he had maintained a second residence since his days at Lorain.

Moxham was not idle for long. When Coleman du Pont decided to initiate the purchase of the Du Pont Company in 1902, he called upon his old mentor from Johnstown and Lorain to serve as his confidant and advisor through the delicate maneuverings. After the company was purchased and Coleman became its President, Moxham served on its Board of Directors and was placed in charge of Product Development. He and his family moved to Wilmington in 1903 and became part of the du Pont family circle until 1915 when Pierre took over the Presidency by buying out Coleman's interests in the company.

After leaving the Du Pont Board of Directors in 1915, Moxham moved back

to Long Island to form his own powder company but was unsuccessful in securing

defense contracts from the government. Since he had never become a naturalized

citizen of the United States, the U.S. government was also not inclined

to take up his offer of organizational and production expertise during

the First World War. After the war when Moxham was already well into his

sixties, he embarked on a series of ore purification experiments in Goshen,

West Virginia and later in the greensands of Odessa, Delaware. Into these

projects, Moxham sank most of his personal fortune with only modest results.

On several occasions, Pierre du Pont invested in the enterprises when they

appeared close to bankruptcy. By 1929, Moxham was no longer able to work

in Odessa and returned to Long Island to live in a small apartment secured

him by his son Egbert. He died quietly on May 16, 1931 at the age of seventy-six

and was returned to Louisville for burial in his family plot in the Cave

Hill Cemetery.

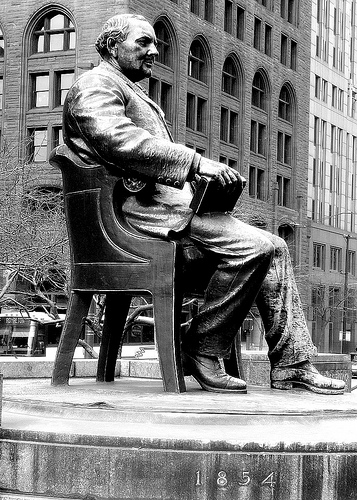

XVI. Tom L. Johnson and the Progressive Movement

By 1890, Tom Johnson's interests had turned primarily to politics and he became a leading progressive and a devotee of Henry George. After two fairly undistinguished terms (1891-1895) representing Cleveland in the U.S. House of Representatives, Johnson divested himself of most of his railway and steel investments and entered local politics. He emerged as a major political figure in Cleveland, serving four terms (1901-1909) as mayor. Deeply committed to progressivism, he took up the battle against corporate interests that exploited the common man and used his position as mayor to initiate political reforms. In a dramatic turnaround from his earlier entrepreneurial days of accumulating capital wealth through the acquisition of monopoly franchises, Johnson pressed for public acquisition and operation of city services such as water, electricity and street railways.

The later years of Johnson's career were more difficult. By the turn of the century, he was revered around the country as one of the great progressive mayors of his day. He was also the financial confidant to some of the major figures in the steel and street railway businesses, including both Coleman and Pierre du Pont, and had amassed a personal fortune estimated at between five and ten million dollars. When his brother Albert died prematurely in 1901, Johnson began supporting Albert's railway and land investments with his own capital. But the Panic of 1907 brought Albert's financial holdings to the brink of collapse. Meanwhile, Johnson's son Loftin was never able to make his own way in various failed business enterprises backed by his father and was a constant drain on family resources. Johnson's daughter married disappointingly in 1907 and after giving birth to a daughter the next year, divorced and returned to live with her parents in Cleveland.

After his defeat for reelection to a fifth mayoral term in 1909, Johnson turned his attention to his family's deteriorating financial situation. Albert's estate had become virtually worthless and taken much of Johnson's personal wealth with it. In 1910, he became very ill but struggled through several public appearances on behalf of progressive issues and candidates. He died the next year at age 57. After a funeral procession in Cleveland, he was buried in a family plot in Brooklyn's Greenwood Cemetery near the final resting place of Henry George. Among his pallbearers were some of the leading progressives of the day, William Jennings Bryan, Frederick Howe, Lincoln Steffins, Henry George, Jr., and his old friend Arthur Moxham.

%20intersection%201924.jpg)

XVII. The Johnstown Foundry and Switch Works

The legacy of the Johnson Company continues to the present day. Its sophisticated rail mill, switch works and foundries in Johnstown manufactured the steel rails and track work on which many of the early electrified street railways ran from the late 1880s through the early 1920s. Scholarly histories have already documented the significant role played by the early street railways in the development of American cities and their suburbs, but rarely has the Johnson Company's contribution to the technology of the railways been recognized or mentioned. Even in the more technical histories of electric street railways, one seldom finds reference to track design and construction.

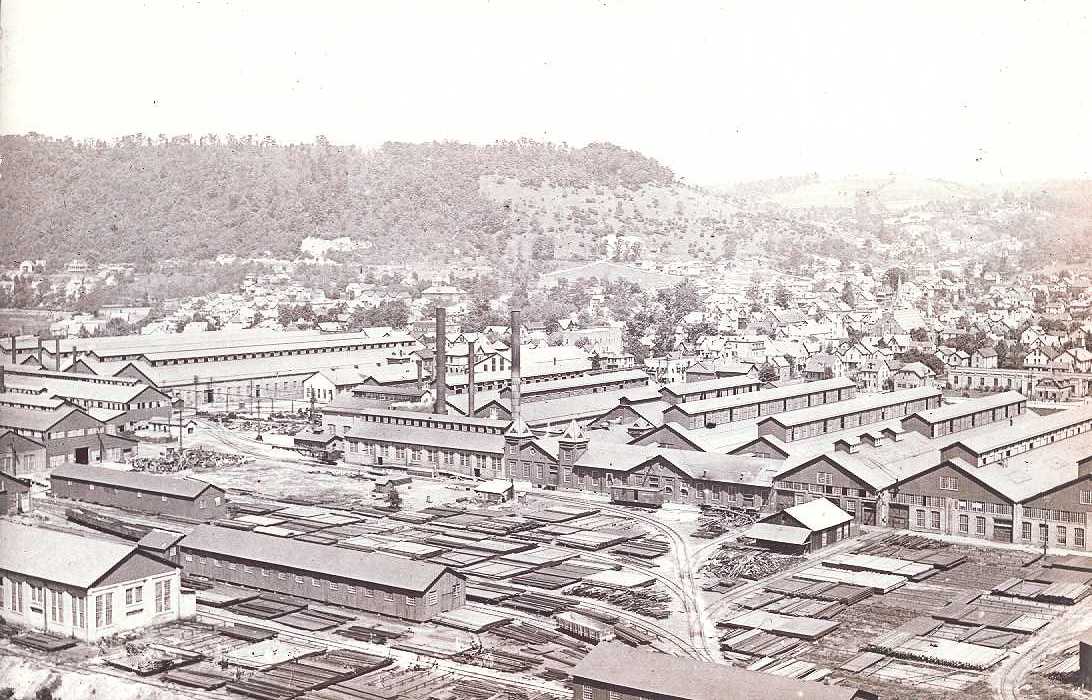

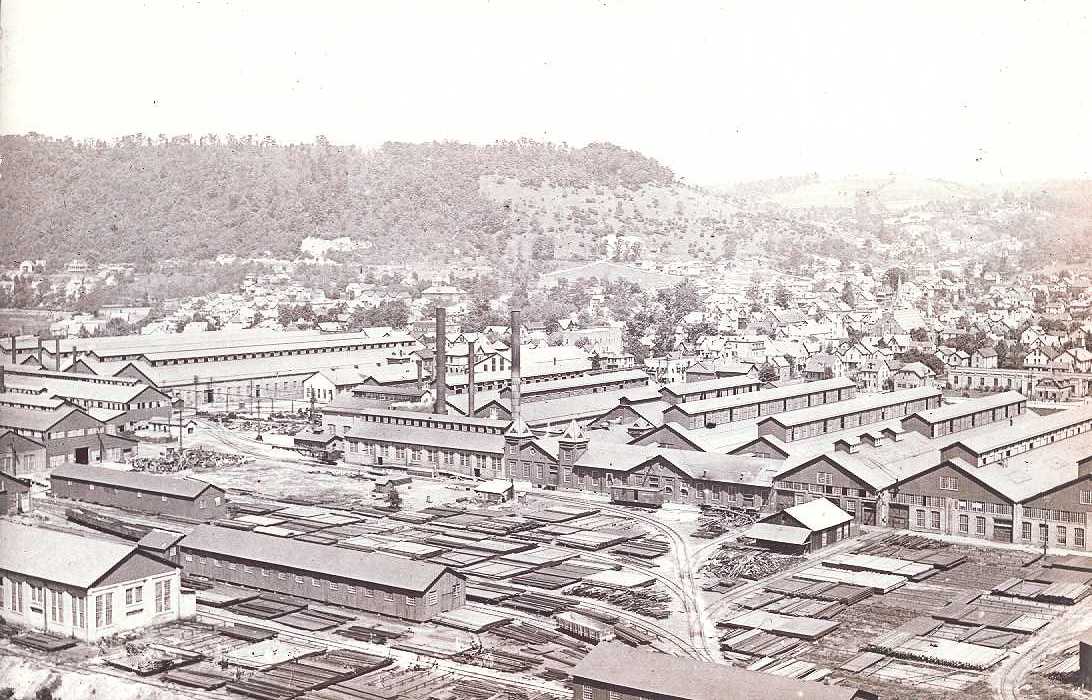

But it was not forgotten in Johnstown. After the merger of Federal Steel into the U. S. Steel Corporation in 1902, the Johnstown mill continued its principal role as an internationally prominent fabricator of railroad and street railway track work. Its steel foundry was expanded and became specialized within the U.S. Steel orbit as a maintenance mill, casting steel rolls and other mill parts. Between 1902 and 1907, the wooden structures of the switch works were replaced with permanent brick bays (known as the Upper Shops) and the boiler house and electrical department enlarged. A second set of large bays (the Lower Shops) was completed to allow the milling of machine parts and rolls, and a metallurgical department was added near the steel foundry. By 1907, the mill employed over 1,300 men.

The plant's maintenance role continued to expand through the first two decades of the twentieth century as demand for street railway and interurban track work first leveled off and then inevitably declined. After World War I, an electric foundry was added and the mill began to produce mining cars. And while its product line did not substantially change after the 1920s, the plant's designation within U.S. Steel did change. In 1935, the parent corporation consolidated three of its steel operations, Carnegie Steel, Illinois Steel and Lorain Steel, into a single corporation known as Carnegie-Illinois. The Johnstown mill became known as its Lorain Division. In 1948, Carnegie-Illinois officially retired from the manufacture of steel rails and changed the local plant's designation to the Johnstown Works.

Even during the 1950s, seventy years after its founding, the Johnstown Works was considered one of the foremost suppliers of specialty track work for street railways, railroads, and industrial and mining operations. But with the terminal decline of street railways after World War II, the specialty track work that had been the trademark of the mill since 1888 had little future. On November 30, 1959, U.S. Steel announced cessation of track work operations altogether and concentrated production at the Johnstown mill on rolls and other castings to serve its other plants. In fact, an expansion of the plant's roll capacity was completed in the late 1960s with the installation of a new electric furnace in its No.2 steel foundry, on the exact site of the original roll train of the Johnson Company rail mill.

With the decline in competitiveness of the American steel industry in the international market during the 1970s, U.S. Steel followed the pattern of other big steel producers and trimmed down their operations. In some plants, unprofitable product lines were eliminated and operations became specialized as mini-mills. In others, the entire operation was closed down. In 1984, the choice was pressed on the Johnstown Works, and after intricate negotiations and financial arrangements, including assistance from federal, state and local governments, the plant site was sold to an investment group headed by John Sheehan and including several previous local managers from U.S. Steel.

That group formed the Johnstown Corporation and reopened the site in 1985 as a mini-mill specializing in small and large steel castings and other types of fabrication. In its first years, the principal customer was U.S. Steel, which still needed many of the Johnstown mill's specialty castings for maintenance of its other operating plants. But the Johnstown Corporation expanded its product line of high quality steel and alloy castings, invested heavily in continuous casters and laser technology, and was able to reduce its dependence on U.S. Steel orders. By 1990, the plant employed over 500 men and women.

The legacy of the Johnson Company is therefore still reflected in both the mill and in that part of the City of Johnstown known as Moxham. As a steel foundry, the mill has been producing steel and iron rolls and castings for over one hundred years. Close to six generations of workers, many claiming grandfathers and some even great-grandfathers as their predecessors, have worked in the foundries, milling bays, pattern shops and engineering drawing rooms there. Many of them still gather annually in meetings of the Moxham Oldtimers.

Some of the original buildings constructed by Arthur Moxham between 1888 and 1893 still stand on the mill site, including the General Office (1889-1890), the Drawing Rooms and Laying Out Floor (1893) now known as the Engineering Building, the original machine shop (1891) now known as the Middle Shops, the track welding shop (1892) now known as the Pattern Shop, and core cupola section of the iron foundry (1891). Even the old pumping house, used between 1892 and 1895 to pump water out of the Stony Creek through an underground brick viaduct to cool the rolls in the rail mill, still stands on the river bank as a peripheral pattern storage building. They remain as a testament to the brief but glorious history of the Johnson Company in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.