|

John D. Norton

Formal Approaches

to Inductive Inference

|

|

home >> research

>> induction and confirmation: formal approaches |

|

The probability calculus is not the universal logic of induction;

there is no such thing. An axiom system disassembles the probability

calculus into distinct notions about induction, which it is urged,

may be invoked independently to tailor a logic of induction to the

problem at hand. The probability calculus fails as the inductive

logic of certain indeterministic systems. |

"Probability Disassembled," British Journal for

the Philosophy of Science, 58 (2007), pp. 141-171. Download.

|

|

Forming the dual is a familiar operation in logic and mathematics.

Truth is the dual of falsity; and (A or B) is the dual of (A and B).

Here I develop the corresponding notion for additive measures, such

as probability measures. The resulting dual additive measures are

degrees of disbelief and turn out to obey their own peculiar

calculus. An ignorance state is conveniently characterized as one

that is self-dual. |

"Disbelief as the Dual of Belief," International

Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 21(2007), pp. 231-252. Download. |

|

What if, like me, you don't think that the probability calculus is

the One, True Logic of Induction? Then you want to know what other

logics are possible. Here I map out a large class of inductive

logics that originate in the idea that the inductive support B

affords A, that is "[A|B]," is defined in terms of the deductive

relations among propositions. I demonstrate some very general

properties for these logics. In large algebras of propositions, for

example, inductive independence is generic in all of them. A no-go

result forces all the logics to supplement the deductive relations

among propositions with intrinsically inductive structures. |

"Deductively Definable Logics of Induction,"

Journal of Philosophical Logic. 39 (2010),

pp. 617-654. Download.

For a less formal development, see "What

Logics of Induction are There?" in Goodies. |

|

Non-trivial calculi of inductive inference are shown to be

incomplete. That is, it is impossible for a calculus of inductive

inference to capture all inductive truths in some domain, no matter

how large, without resorting to inductive content drawn from outside

that domain. Hence inductive inference cannot be characterized

merely as inference that conforms with some specified calculus. |

"A Demonstration of the Incompleteness of Calculi

of Inductive Inference" British Journal for the Philosophy of

Science, 70 (2019), pp. 1119–1144.

Download.

"The Ideal of the Completeness of Calculi of Inductive Inference: An

Introductory Guide to its Failure" Draft |

|

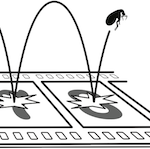

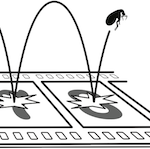

An infinite lottery machines chooses without favor among a

countable infinity of outcomes. This sort of selection creates

well-known problems for probability theory. But is it really

physically possible to construct such a machine?. |

"How to Build an Infinite Lottery Machine" 8 (2018),

pp. 71-95.

(with Alexander R. Pruss) Correction to John D. Norton “How to Build

an Infinite Lottery Machine, ” European Journal for Philosophy

of Science. 8 (2018), pp. 143-44.

Download. |

|

All efforts to design an infinite lottery machine using ordinary

probabilistic randomizers fail. This failure is not a result of a

lack of imagination in design. It is assured by a familiar problem

in set theory: we know no way to construct probabilistically

nonmeasurable sets. |

"How NOT to Build an Infinite Lottery Machine." Studies

in History and Philosophy of Science. 82(2020),

pp. 1-8. Download. |

|

Matt Parker and I disagree on whether a multiple of four is less

likely than an even number in a drawing from an infinite lottery.

|

"An Infinite Lottery Paradox" Axiomathes

32, supplement issue 1 (2022), (Special Issue Epistemologia

2022), pp. 1-6. Download.

|

|

Here is an illustration of how it is possible in a principled way

to devise a strict weakening of the probability calculus that is

non-additive and not prone to the Bayesian's notorious problem of

the priors. It represents an interesting technical exercise, but I

regard it as superceded by the analyses of the later papers above. |

"The Theory of Random Propositions," Erkenntnis,

41, 1994, pp. 325-352.

|

|

|