| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

Linked supplementary document:

Conformal Transformations: How to Tame Infinity

| The spacetime diagram we used so far for visualizing black holes is not a very good representation of a black hole. It cannot represent the continuous spacetime trajectory of a body falling in as a continuous curve. There is no point in it at which the body is at an event on the event horizon. It does not even show all the structures present in a black hole. There are other parts to spacetime we do not see on it. | In the figure below, the event horizon is approached by the traveler as the traveler moves up the world line in the diagram. When the traveler moves down the worldline in the diagram, the traveler has passed the event horizon. That means that the event horizon is above the top of the diagram and not shown. No matter how much we extend the diagram upwards, the event horizon will always be past the edge of the diagram. |

The diagram also breaks with our familiar slogan "time goes up--space goes across." Inside the event horizon for this figure, time goes across in the sense that horizontal lines pointing towards the singularity are future directed timelike curves.

There is a better way of representing the black hole. It is to use a conformal diagram that brings in infinities and represents them as points on the diagram. These diagrams will include purely fictitious points like the end points of the timelike worldlines of objects that persist for infinite time. There is no such end point, but they will be on the diagram and prove very useful to us.

At first the idea of a diagram that represents such fictitious points at infinity might seem a little mysterious. But the idea is actually quite familiar in another context, that of perspective drawing. Imagine an infinite, two dimensional Euclidean plane criss-crossed by a grid of lines. An ordinary drawing, looking straight down from overhead, cannot capture more than a small portion of the plane.

| We know some of properties of the grid. All the

north-south lines are parallel and never meet. They just go off to a

north and a south infinity. Sometimes we say that these parallel

lines "meet" at infinity. The talk

suggests a kind of Valhalla for valiant, but departed lines where

they all finally meet to celebrate battles lost and won.

Of course we don't intend that "meet at infinity" talk to be taken literally. There is no place at infinity where the lines meet. All we really mean is that the lines go off indefinitely in the same northerly (or southerly) direction. The place at infinity where we imagine them meeting is just a reification of the idea that they persist indefinitely in going in the same direction. |

The north-south lines are crossed by east-west lines. An analogous story can be told for them. They are parallel and "meet" at a different infinity. This "meet at infinity" talk is just a way of reifying the different directions in which two sets of lines persist in moving.

| Now imagine that we move our gaze towards the horizon from our overhead position. We can now see an infinite portion of the plane. If we make a drawing of what we see, we can see the entire length of infinite lines, or at least one half of them extending infinitely. |

In this new perspective drawing, we can actually see the points at infinity at which the parallel lines meet. These points at infinity lie on the horizon. All the north-south lines meet at one point on the horizon. It is the North vanishing point, but let us call it the "north-infinity." All the east-west lines meet at a different point on the horizon. It is the East vanishing point, but let us call it the "east infinity."

Of course no one thinks these points represent a real place on the plane. The fact that a line in the figure actually connects to the north-infinity point just encodes the fact that the line really keeps going north indefinitely. Analogously, the fact that a line in the figure connects to a different point at infinity, the east-infinity, just encodes the fact that the line really keeps going indefinitely in a different direction, east. In short, the point on the horizon is a fictitious point that represents the infinity never actually reached by the lines.

| A traditional perspective drawing does not show us the full, infinite plane. For that, we need an even more distorted image, an overhead view such as produced by a camera with a "fisheye" lens. |  The horizon in all directions in visible in this fisheye image of a mountaintop. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mountaintop_fisheye.jpg |

Fisheye image shows all four walls of the

banquet hall in Hellbrunn Palace, Salzburg.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hellbrunn_banqueting_hall_ceiling_fisheye_projection.jpg

Finally perspective drawings must pay a price for being able to show the infinite length of a line. In the overhead view, a drawing can be scaled properly. That means that one inch on the drawing can always correspond to one mile in the real plane. This cannot be done in a perspective drawing. A length of one inch in one part of the perspective drawing might correspond to one mile in the real plane. But one inch in a part of the drawing close to the points at infinity might represent a much greater--even infinite--distance in the real plane.

| Just like the overhead view of the North-South and East-West lines, the spacetime diagrams we have used so far for a Minkowski spacetime only show a small portion of the spacetime. We can also have a diagram in which the points at infinity become visible. We used a perspective transformation before. This time we shall use a "conformal" transformation to produce a "conformal diagram." | A conformal transformation has the property of

leaving lightlike curves unaffected, but stretching and shrinking

times and spatial distances. We need not pursue the details here.

They are in the linked document: Conformal Transformations: How to Tame Infinity |

| Recall that a timelike geodesic is just a point moving inertially and a spacelike geodesic is just the familiar straight line of ordinary geometry. A lightlike or null geodesic is the curve traced by a light pulse moving freely. | A Minkowski spacetime has many different sorts of infinities. They come from the types of curves in the spacetime. It has timelike, space and lightlike geodesics. Each has their own infinity. Note as before that these infinities in the diagram are fictitious points. There is no point in spacetime corresponding to them, just as there is no point in space corresponding to the vanishing point of a perspective drawing. |

| First, here is the conformal

diagram of a Minkowski spacetime. This is the complete

spacetime. It includes all of the infinity of space and the infinity

of time through which things persist.

This diagram gives the simplest case in which we consider just one dimension of space. Note the three types of infinities: timelike, lightlike and spacelike. They correspond to the different vanishing points in an ordinary perspective drawing. Let us investigate each in turn. |

| Here is an ordinary Minkowski spacetime with the timelike geodesics that stretch from the infinite past to the infinite future. The diagram can only show a finite portion of each geodesic. |

| Here are the same timelike

geodesics shown on the conformal diagram. We can now see

them in their entirety, stretching from past timelike infinity i-

to future timelike infinity i+.

It is important to note that the distances along the curves do not represent properly scaled times elapsed. 1/4" length of the timelike geodesic in the middle of the curve might represent a day of elapsed time. The final 1/4", at the end of the geodesic where it joins i+, corresponds to an infinity of time elapsed. Note that we can only be assured that timelike geodesics--corresponding to unaccelerated motions--will stretch from past timelike infinity i- to future timelike infinity i+. If a timelike curve has sufficient acceleration, it can originate or terminate in the lightlike infinities. While such timelike curves are possible, they are exceptional cases. Most ordinary timelike curves that represent ordinary motions will terminate in the two timelike infinities. |

| Here are lightlike geodesics on a spacetime diagram. they stretch from the infinite past to the infinite future. Only a small portion of each full curve can be shown. |

| Here are the same lightlike

geodesics displayed in their entirety on a conformal

diagram. They extend from past lightlike infinity to future

lightlike infinity. Note that these infinities are not just points,

but a complete line, rather like the line of the horizon in a

perspective drawing.

These infinities are sometimes called "null" infinity and lightlike curves, "null" curves, since the time elapsed along a lightlike curve is zero, that is, "null." The symbol for lightlike infinity is a script i, which looks like

|

| Finally, a Minkowski spacetime is populated with

spacelike curves as well. They form the

spacelike hypersurfaces that are the "nows" of the spacetime.

They extend from infinity to infinity and only a small portion of each surface can be shown. |

| Here are spacelike curves

taken from these spatial hypersurfaces. They are shown in their

entirety and stretch from one spacelike infinity i0 to

another spacelike infinity i0.

Distances in the figure no longer correspond to properly scaled distances in space. 1/4" at the center of figure on one of these curves may correspond to a mile; the last 1/4" of the curves, where they connect to i0, corresponds to an infinite distance. |

| That light travels at the same velocity c is encoded into the diagrams by the particular fact that all lightlike geodesics are oriented at 45o to the vertical. This important geometric fact is shown in the figure. |

| That timelike curves--geodesic or not--represent

points moving at less that the speed of light has a similar

geometric expression.

Such curves are, at every event, pointed in a direction that makes an angle of less than 45owith the vertical. Since timelike curves generally change their direction from event to event in a conformal diagram, we need to be a little clearer about what this means. It means this. Take any event on the worldline, such as shown in the figure. Bring a straight edge to the event so that the straight edge is tangent to the curve at that event. Then that straight edge must make an angle of less than 45o with the vertical. This must be true of every event on the timelike curve. |

The important properties of a

conformal diagram are threefold:

--Time once again always goes up in the figure; and space goes across.

--Lightlike curves are always at 45o. The light cones no longer

tip over in the figure. Timelike curves are always directed at less than

45o with the vertical; and spacelike curves are always at

greater than 45o with vertical.

--The same intervals on the figure no longer correspond to the same times

elapsed and spaces covered. An interval of say one inch on a timelike

curve in the middle of the diagram might correspond to one day of elapsed

time. The last inch of the timelike curve terminating in i+

corresponds to an infinite time elapsed.

Would you like to try whether your grasp of the conformal diagram of a Minkowski spacetime is solid? Below are two sets of world lines. Each is drawn first in the familiar Minkowski diagram. The exercises are to see if you can predict how the same world lines will look on the conformal diagram of the Minkowski spacetime. To do the exercises, do not read through too quickly. Once you have seen the ordinary spacetime diagram, pause and think through how the corresponding conformal diagram will look.

First we have three timelike geodesics which might represent three inertial observers at rest in some inertial frame of reference. They appear as the three timelike worldlines drawn vertically in the ordinary spacetime diagram of a Minkowski spacetime:

We now add the worldlines of three inertial observers in a different frame of reference. They will be represented by the three diagonal lines in the ordinary spacetime diagram above. These new observers are moving uniformly from left to right in the first frame of reference.

As before, we must imagine that all these worldlines are extended indefinitely into both the past and future. The dotted lines are hypersurfaces of simultaneity of the first frame of reference. They are spacetime geodesics that also extend indefinitely in space.

How will these two sets of worldlines appear in a conformal diagram of the Minkowski spacetime? We already know how the first set of worldlines will appear. They must start in past timelike infinity i- and end in future timelike infinity i+:

What about the worldlines of the second frame? We can use the points of intersection of the worldlines of the two frames to guide us. They are marked in the original diagram as small circles. Some are labeled A, B and C. We can map those points of intersection onto the conformal diagram, using the dotted hypersurfaces of simultaneity as guides.

The principle employed here is that the conformal transformation that takes us from the original Minkowski spacetime diagram to the conformal diagram is continuous. Informally, that just means that the transformation does something like stretching or contracting a rubber sheet in different ways in different places. Under this sort of transformation, the order of the lines and the points of intersection are preserved. It is only the distances between them that are changed. Worldlines that do not cross cannot be made to cross; and ones that do cross cannot be uncrossed.

The result is that we can discern how the middle parts of the worldlines of the second frame will appear. We identify the points of intersection in the conformal diagram and then just draw curves through them:

It is now easy it to draw in the remaining parts of the worldlines of the second inertial frame of reference. As with the first frame of reference, the worldlines must start in past timelike infinity i- and end in future timelike infinity i+. We just continue the middle parts of the worldlines to both future and past, so that they terminate in the appropriate timelike infinity. In doing this, we make sure that we introduce no new intersections.

Here is a second exercise.

| Consider a light signal

that bounces back and forth for all time over some fixed

distance in an inertial frame of reference. The original spacetime

diagram of the Minkowski spacetime is shown on the right. The

bouncing light signal is represented by the zig-zagging line. It

extends indefinitely into the past and future. To help us locate the corresponding lines on the conformal diagram, two timelike geodesics, representing points at rest in the inertial frame of reference, are also shown as dotted lines. They also extend indefinitely into the past and future. How will the conformal diagram appear? |

| The easiest way to the conformal diagram is first

to draw in the two timelike geodesics. They must start in past

timelike infinity i- and end in future timelike infinity

i+. We know that the curves representing the bouncing light signal must be confined between these two timelike geodesics for all time. We also know that each segment of the light signal's curve must be a straight line at 45o to the vertical. Combining, we arrive at the zig-zagging line shown at left in the conformal diagram. Since the light signal will bounce infinitely often in the future, we must continue the zig-zags in the conformal diagram infinitely often as future timelike infinity i+ is approached. The same infinity of oscillations must arise as we approach past timelike infinity i-. The figure does not show this infinite oscillation since the zig-zags grow arbitrarily small as we approach the two timelike infinities and eventually become impossible to draw. |

| To get a better sense of how we fit

infinitely many zig-zags into the conformal diagram, here

is an enlarged view of the part of the conformal diagram close to

future timelike infinity, i+. There is an infinity of

zig-zags in the lightlike curves in this tiny part of the diagram. We could continue to enlarge just this portion of the diagram and it would look the same. Since there is an infinity of zig-zags, we could never enlarge enough to see the last "zag." There is no last "zag." |

It is not at all obvious that we have gained anything with the conformal diagram of a Minkowski spacetime; we just seem to be saying what we already knew in a new, unfamiliar way. In the case of a black hole, however, the conformal diagram makes it easy to see properties of the spacetime that were formerly quite hard to see.

| Let us reconsider the case of a black hole that was produced by a gravitationally collapsing, sphere of matter. This is a black hole of the simplest type, one associated with a Schwarzschild spacetime. This black

hole has no electric charge and no angular momentum (i.e. it isn't

spinning). You'll see immediately how unrealistic that is. Any collapsing

cloud of matter is likely to have a very complicated structure and

will certainly not be so perfectly symmetric that it collapses without turning.

However its simplicity makes it easy for us to see its properties

We will draw the conformal diagram that corresponds to just one spatial dimension of the black hole. The figure we saw in the last chapter included two dimensions of space and is reproduced in the right. The conformal diagram below will only consider the one dimension of space that is indicated by the shaded region. The region starts at the center of the collapsing matter and extends radially outward. |

| Here is the conformal diagram that shows only this single dimension of space. To read the diagram,

start at the bottom. The worldlines of collapsing matter come out of

past timelike infinity, i-. As they proceed upward

through time, they collapse onto themselves.

They have formed a black hole when collapsed sufficiently to generate an event horizon, which is indicated as the line at 45o in the upper part of the diagram. Then all the matter ends in the singularity, which is a horizontal line at the top of the figure. The novelty is that the spacetime is now divided into two regions, marked I and II. Region I is an ordinary spacetime--in fact it is the familiar Schwarzschild spacetime we've spent so much time looking at. It has the familiar timelike, lightlike and spacelike infinities. if we pick an event far from the event horizon, the spacetime in its vicinity will be just the same in its geometric properties as if there is no black hole, but just an ordinary gravitating body of the same mass in its place, such as a huge star. Region II is the region inside the black hole, beyond the event horizon. |

| Let us now add the worldlines of a planet

and a traveler that leaves the planet and falls into the

black hole.

The planet's worldline originates in past timelike infinity, i-, and terminates in future timelike infinity, i+. The planet has a calm, infinite life. The traveler leaves the planet and passes from region I into the black hole region II and into the singularity. |

| The event horizon

marks the boundary of no return. We can see that by recalling that a

traveler must alway travel at less than the speed of light. That is,

the traveler's worldline must always be at less that 45o

to the vertical.

That means that the traveler can always pull away from the black hole, as long as the event horizon has not been passed. If the traveler strays close to event horizon at A, or closer at A', or even closer at A'', it is evident from the geometry of the figure that the traveler can always find a trajectory that will end in future timelike infinity. For the event horizon itself marks the boundary of a curve 45o with the vertical. This last effect shows why event horizons are always represented by line at 45o to the vertical. They represent the limit of all motions of massive bodies that move at less than the speed of light. That limit is unrealized by any massive body moving at less than the speed of light and coincides with a lightlike curve, that is, a line at 45o to the vertical Once the event horizon is passed--say the traveler is at event B--it is too late. All trajectories at less than 45o with the vertical terminate in the singularity. Take a moment; stare at the figure; and convince yourself that all this is correct. Remember the key fact: the traveler's worldline must everywhere make an angle of less than 45o with the vertical. |

| Finally we can use the conformal diagram to trace

the signals sent by the traveler back

to the planet.

The diagram shows the traveler sending out light signals, which propagate along the 45o trajectories light follows. The diagram shows that only light signals emitted before the traveler passes the event horizon will make it to the planet. Once the traveler has passed the event horizon, all the light signals will end up in the singularity. Turning it round, if a planet observer waits and watches while the traveler falls into the black hole, the rate of signals received will slow down. The planet observer would need to live for all eternity of time to intercept all the signals sent out by the traveler before the traveler reaches the event horizon. If we imagine that the traveler emits these light signals at equal intervals of proper time, the planet observer will find them to arrive at greater and greater time intervals. Thus the planet observer will find the traveler's temporal processes to have slowed down and eventually become frozen. (This effect is also the basis of the red shifting of light from a body closer to a massive body.) |

Here is an animation showing how the light signals propagate.

The black hole formed by collapsing matter is the simplest black hole. It is far from the most interesting. By solving Einstein's field equations--that is by consulting his book of universes--we find a closely related black hole. It is like the one we've just seen, but was not formed by collapsing matter. It has existed for all time. It is known as the "fully extended, Schwarzschild black hole."

| We can construct one mathematically by starting with just the matter free part of the Schwarzschild spacetime. We then extend that piece of spacetime with more matter free spacetime by means of Einstein's gravitational field equations. If we keep extending the spacetime in that way, we end up with a new and interesting black hole. Here is a conformal diagram of it. | Recall the jigsaw puzzle analogy. The extension is like adding more pieces to an incomplete jigsaw puzzle. |

The great novelty of the new black hole is that it is twice the size of the old one. On the "other side" of the event horizon is a complete duplicate of the exterior of the black hole, the region III. Just as region I is an infinite space surrounding the black hole, region III is another infinite space just like it.

Everything that happens in region I can happen in region III. Both can have planets and moons and space travelers. In region I we can have a planet that passes from past timelike infinity to future timelike infinity and sends out a traveler who falls into the black hole. And we have the same thing for region III: a planet that passes from past timelike infinity to future timelike infinity and sends out a traveler who falls into the black hole.

The second duplication is equally striking. The counterpart of the singularity in the future is a new singularity in the past. It is surrounded by a region that duplicates region II, the inside of the black hole. This new singularity/region IV behaves like the reverse of the future singularity. Just as things fall into the future singularity, things fall out of the past singularity and into the spacetime. For this reason, the structure is called a "white hole." The diagram shows timelike worldlines of things that are ejected by the past singularity into the regular spacetime regions I and III.

What can come out of the singularity? Ejection from it is the reverse process in time of falling into the future singularity. So anything that can fall into the future singularity can be ejected from the past singularity. That means anything--dinosauars; the socks you lost; TVs showing re-runs of "I love Lucy"; and so on. You might expect that the theory would say that ejecting odd things like that is vastly improbable. The awkward thing is that the theory assigns no probabilities to these possibilities. It just says that this is possible and that is impossible. Ejecting dinosaurs is as possible as ejecting the chaotic gush of hot particles and radiation that seems most natural.

| The past singularity is a "naked singularity." That means it is not hidden behind an event horizon, like the future singularity, and things that come out of it can reach us. | Before you dismiss the dinosaurs and TVs as crazy, recall that we have one clear example of the existence of a naked singularity. That is the big bang of cosmology. That singularity certainly did eventually eject dinosaurs and TVs, although it did take a while for them to form from the material ejected! There's no news on your socks, however. Did you look behind the drier? |

What about traveling from region I to the other world of region III? The idea is hugely appealing (if we set aside worries about tidal forces). We would throw ourselves into a black hole, which would then prove to be the portal to another world! Alas, it is clear from the conformal diagram that passing over into the other world is prohibited to beings like us who cannot travel faster than light. Here is a worldline of a traveler who makes the passage. You'll see that it is inevitable that, at some point, the curve must make an angle of more than 45o with the vertical. That is, the traveler must at some point exceed the speed of light. Any attempt by travelers who cannot do this would result in a one-way trip into the singularity.

Proceeding in this way, the conformal diagram enables us to recover lots of information about the fully extended black hole. Is it possible for beings from region I and III to meet somewhere? Yes, in region II. If a traveler falls from a planet into the black hole, how much of the planet's worldline will be visible through light signals to the traveler in the brief moments that remain before the traveler meets the future singularity? Depending on how the traveler falls, an arbitrarily large amount will be visible.

The diagrams shown above are limited in one aspect. The three dimensional ordinary space has two of its dimensions suppressed. The space appears merely as a single line, a one dimensional space, marked below as a "spacelike hypersurface."

Each point on the line represents all points in a three-dimensional space at some fixed radial distance from the center of the black hole. The situation is similar to ordinary geometry: the set of all points at a fixed distance from some origin point is the two-dimensional surface of a sphere enclosing the origin. The same is true here. For each fixed radial distance, these points form the two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional sphere enclosing the black hole.

Imagine that we restore the two missing dimensions. Then each point on the hypersurface becomes the two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional sphere of the ordinary three-dimensional space enclosing the black hole. As we proceed from one side to the other, the enclosing spheres get smaller and smaller in area. However, since the geometry is not Euclidean, the spheres do not lose area as fast as you would expect when we move to spheres successively closer to the event horizon. We already saw this effect in the Schwarzschild spacetime of massive bodies like the sun. In this case, however, the effect is stronger. The spheres reach a minimum size and then expand.

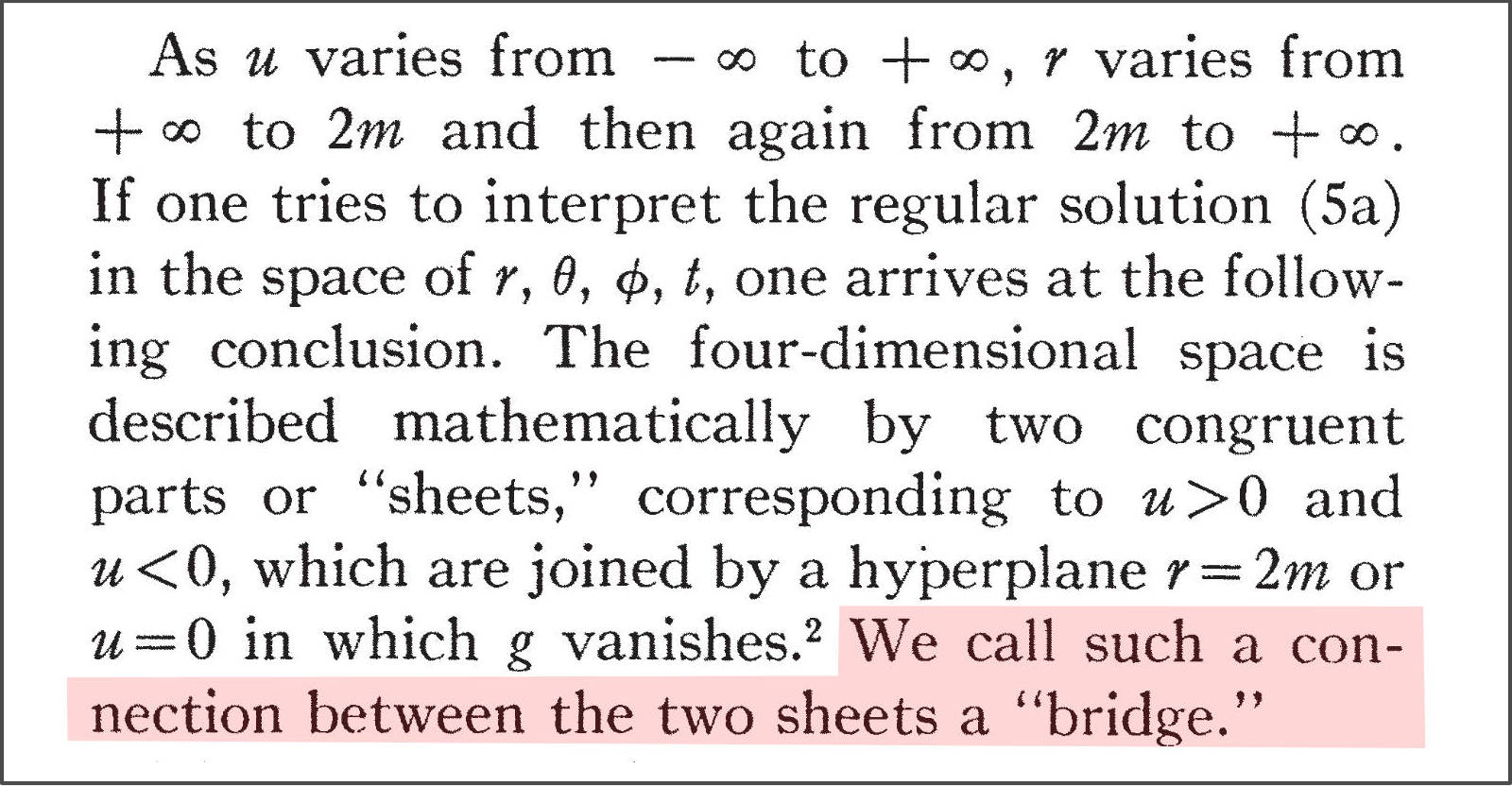

| The effect can be seen in an embedding diagram in which we show only two of the three dimensions of the spheres. The spheres are now represented by circles. The circles become smaller as we proceed from region I to III. However once they reach a minimum size, they begin to expand. The diagram is very suggestive. Since the structure was identified and called a "bridge" by Einstein and his collaborator Nathan Rosen in 1935, it is now called an Einstein-Rosen bridge that connects the two worlds of regions I and III. In a sense it is bridge, but it is only one that travelers who can go faster than light can cross. | The figure below of the Einstein-Rosen bridge is an extension of the familar embedding diagram of the space around the sun, in which the space appears to be stretched like a rubber membrane. |

For the particular spacelike hypersurface shown in the conformal diagram, the narrowest part of the neck is located exactly at the intersection of the two event horizons of the regions I and III. (This was the case Einstein and Rosen originally considered.) That lets us determine the size of narrowest part of the neck. Each of the circles in this bridge picture corresponds to a three dimensional sphere in ordinary space (that it impossible to draw informatively in the picture). The smallest circle at the narrowest part of the neck corresponds to a sphere in space that is the spatial location of the event horizon of the two regions I and III at the time picked out by the spacelike hypersurface. Its size is determined by the mass parameter of the black hole. If the mass parameter is small, then the sphere will be small. If the mass parameter is large, then the sphere will be large.

Here is the paper in which Einstein and Rosen identified their bridge:

Here is their naming of the bridge (p. 75):

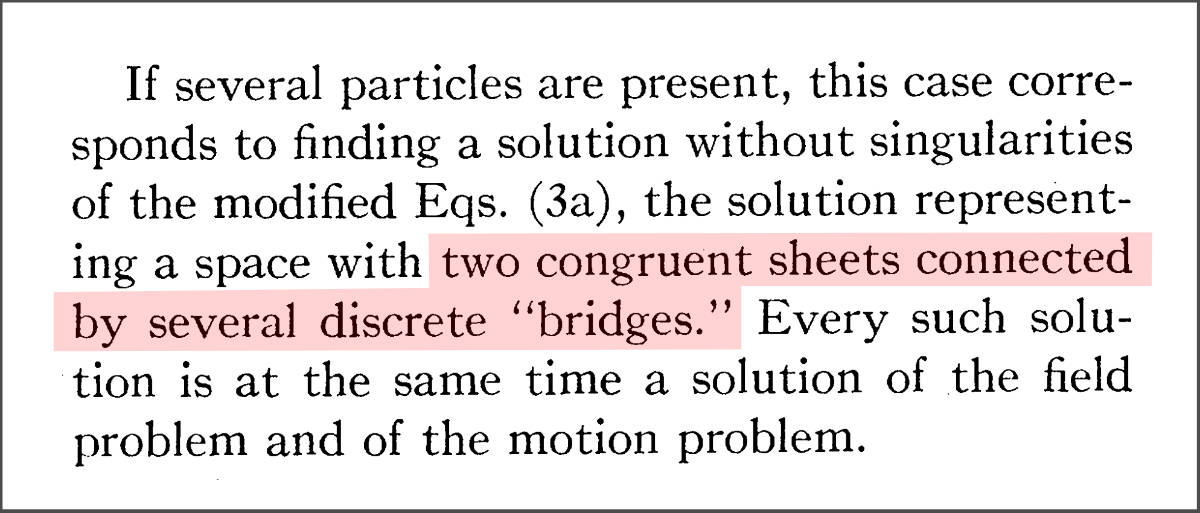

Einstein and Rosen's proposal, however, was not a contribution to black hole physics. We have already seen that Einstein harbored great suspicions about black holes and even came to argue that they could not form. Rather the proposal of the bridge came as part of Einstein's attempt to represent particles as geometric structures in spacetime. The bridge identified in the above passage was a short-lived proposal by Einstein and Rosen for the nature of massive, uncharged particles. Here is their description of the proposal for many such particles (p. 76):

Consider, for example, four massive, uncharged particles in space. We might ordinarily think of them as lumps of matter-stuff scattered over ordinary space:

Einstein and Rosen now proposed that there there is no matter-stuff there at all. There is only the pure geometry of what we would otherwise think of as empty spacetime. The particles are really four bridges in that geometry connecting two sheets of spacetime:

Why might this account of particles be appealing? It would seem that we have replaced a simple idea by something very complicated. An ordinary bit of matter has been replaced by the exotic geometry of structures that connects two worlds. The appeal for Einstein and Rosen lay in Einstein's enduring quest for a "unified field theory." If ever such a theory could be found, it would have only a single unified field, such as the one responsible for the geometry of spacetime in the general theory of relativity. There would be no additional matter fields to represent particles as something added to this field. If particles really were these bridges, then Einstein could hope that his single field could accommodate them and also the geometry of spacetime.

The proposal does not endure

in Einstein's publications. It seemed to pass away as fleeting conjecture.

| A complication is that the event horizon of the Schwarzschild spacetime is included in the geometric structure of the particle. This in spite of Einstein and Rosen's dubious insistence that spacetime becomes singular at the event horizon.(This insistence has been explored in an earlier chapter.) They escaped the problem here opportunistically by proposing a modification to the gravitational field equations. The modified equations allowed them to treat the event horizon in a way that avoided the problematic character that had troubled them. | From the paper, p. 73: "For a singularity brings so much arbitrariness into the theory that it actually nullifies its laws. ... Every field theory, in our opinion, must therefore adhere to the fundamental principle that singularities of the field are to be excluded." |

This case of the Schwarzschild black hole already affords many interesting possibilities. It is only the beginning of the immense array of possibilities opened up by black holes. To give just a taste of this array, we can look at a spherically symmetric black hole that has the addition of an electric charge. One might imagine that adding a little electric charge could not possibly change things very much. That is not so. The new spacetime that results is the "Reissner-Nordstroem" spacetime with its associated black hole.

| The conformal diagram in the case of smaller electric charges is shown below. It is the fully extended black hole, that is, one that was not formed by the gravitational collapse of charged matter. The diagram is immense in comparison with that of the Schwarzschild black hole. In the figure below, we can only display a portion of it. There are, in it, an infinity of regions I, II and III. The full figure extends up and down the page indefinitely, repeating the pattern shown in this small segment. To get a sense of the immensity of what is displayed, the regions marked I are like the region I above of the Schwarzschild spacetime. They are infinite spacetimes that come arbitrarily close to a Minkowski space as we approach spacelike infinity, i0. | The conformal diagram below is redrawn

from S. W. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis, The Large Scale

Structure of Spacetime. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, p. 158. The "case of smaller electric charge" is, to be more precise, the case of electric charge e and black hole mass m that satisfies e2 < m2, when measured in suitably normalized units. |

The same conventions apply as for the earlier conformal

diagrams. Two dimensions of space are suppressed. Past timelike, future

timelike, spacelike and lightlike infinities are labeled as before: i-,

i+, i0,  -

and

-

and  +. In addition to the

infinity of regions, the singularities--the jagged

lines--are now timelike in their orientation. This has the

extraordinary consequence that a traveler who starts in an ordinary region

I can now fall past the event horizon--one of the dashed lines--and may be

able to avoid the black hole.

+. In addition to the

infinity of regions, the singularities--the jagged

lines--are now timelike in their orientation. This has the

extraordinary consequence that a traveler who starts in an ordinary region

I can now fall past the event horizon--one of the dashed lines--and may be

able to avoid the black hole.

The figure below shows the timelike worldlines of three travelers who fall past the event horizon of a region I. One of them falls into the singularity. The second traveler manages to escape to a whole new region of type I. The third also manages to escape to a new region of type I, but this one is on the other side of the black hole to the one reached by the second traveler. In informal terms, this black hole has opened wormholes in space that travelers can use to voyage to new universes--as long as they can withstand the tidal forces.

This short introduction does not even begin to exhaust all the novel and interesting ideas associated with black holes. We have looked only at the simplest cases. As we have just seen, if we allow that the black hole can carry charge, the associated conformal diagram becomes very much more complicated. Further complications arise if the black hole carries angular momentum (spin) as well. Many new regions corresponding to new worlds appear. It is possible for us to visit some of them without traveling faster than light, if we fall into a black hole and somehow survive the pummeling of tidal forces.

It also turns out that the types of black holes are limited by the factors just mentioned. Once the mass, charge and angular momentum of a black hole are fixed, then all its properties are also determined. That gravitational collapse will always produce a black hole has also been demonstrated in theorems akin to those that demonstrate the inevitability of a big bang singularity. And it has been suggested that when gravitational collapse produces a singularity, that singularity is always hidden behind an event horizon--this is known as "cosmic censorship."

Yet further complications arise if we allow for the quantum nature of matter. It turns out that black holes, especially small ones, become unstable, emit particles and can evaporate. Real black holes in nature are some of the most extreme objects we can access. They have gravity so intense that we must treat them with general relativity, not Newtonian theory; and their innermost parts are so small that quantum theory is needed as well. Because they are general relativistic quantum objects, they have become popular test beds for new theorizing in physics that seeks to unify general relativity and quantum theory. They continue to be the subject of intense theorizing and may be portals not just to other worlds but to the next generation of extraordinary physics.

Copyright John D. Norton. March 2001, October 2002; February 8, 2007, February 23, 2008. November 13, 2018. LInked doc added October 26, 2020. Oct 29, November 2, 2020. February 5, April 14, 2022. November 11, 2024.