| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

This chapter continues the

discussion of the last chapter on morals that we might try to

draw from special relativity. This chapter collects morals that pertain to

the nature of scientific theories, the concepts they use and how we can

have evidence for them.

Einstein eliminated the ether from physics since there were no observable circumstances in which our motion through it could be revealed. This is compatible with a verificationist approach to all propositions. According to it, a proposition is meaningless unless there are circumstances conceivable under which it could be proven true (verified) or at least confirmed.

| Einstein's establishment of special relativity has been judged by many to embody the core insight of a strong movement in philosophy from the earlier part of the 20th century. Hans Reichenbach was a German philosopher who learned relativity theory from Einstein in Berlin in the 1910s and became one of his principal, philosophical interpreters. |  |

| . |  |

Reichenbach wrote in his contribution to the 1949 volume Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, which celebrated Einstein, in his chapter "The Philosophical Significance of the Theory of Relativity" (pp. 290-91) [with my added paragraph breaks]: |

"To advocate the

philosophical significance of Einstein's theory, however, does not mean to

make Einstein a philosopher; or, at least, it does not mean that Einstein

is a philosopher of primary intent. Einstein's primary objectives were all

in the realm of physics.

But he saw that certain physical problems could not be

solved unless the solutions were preceded by a logical analysis of the

fundamentals of space and time, and he saw that this analysis, in turn,

presupposed a philosophic readjustment of certain familiar conceptions of

knowledge.

The physicist who wanted to understand the Michelson

experiment had to commit himself to a philosophy for which the meaning

of a statement is reducible to its verifiability, that is, he had

to adopt the verifiability theory of meaning if he wanted to escape a maze

of ambiguous questions and gratuitous complications.

It is this positivist, or let me rather say, empiricist

commitment which determines the philosophical position of Einstein. It was

not necessary for him to elaborate on it to any great extent; he merely

had to join a trend of development characterized, within the generation of

physicists before him, by such names as Kirchhoff, Hertz, Mach, and to

carry through to its ultimate consequences a philosophical evolution

documented at earlier stages in such principles as Occam's razor and

Leibniz' identity of indiscernibles."

Reichenbach's analysis depends upon comparing Einstein's view with that of his contemporaries:

| Two theories in 1905 | Einstein's special theory of relativity | H. A. Lorentz's electron theory |

| Agreed on what could be observed | moving rods contract, moving clocks slow, ..., no observably distinguishable state of rest. | moving rods contract, temporal processes of moving bodies slow, ..., no observably distinguishable state of rest. |

| Disagreed on the unobserved things posited by theory | no such thing as an ether with a preferred ether state of rest | Motion through

the ether with respect to its preferred state of rest causes rods to

contract and clocks to slow, etc. They do so in just the right amount to prevent us distinguishing which inertial state of motion coincides with rest in the ether. |

One sees in this comparison the essential intuition that guides Reichenbach's analysis: something seems to be wrong with Lorentz's theory. It has an extra element, the ether with its state of rest, that is not present in Einstein's theory, even though both theories make the same prediction.

| The elusive nature of this ether state of rest and Einstein's reaction to it was later captured in the slogan "the difference that makes no difference is no difference." That slogan seems to capture an obvious and simple view. | To illustrate the idea, imagine that I insist that there are pixies in the mountains, but that you will never see them, no matter how hard you search, since they hide perfectly behind the trees whenever you come near. You would surely doubt my assurance and properly suspect that there really are no pixies in the mountains. If their presence leaves no observable trace, my insistence that they really are there looks like a delusion. |

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Page_83_illustration_in_More_English_Fairy_Tales.png public domain image |

|

The "positivism" of the logical positivist

movement was introduced by Auguste Comte in his monumental, six

volume treatise on science, Cours de Philosophie Positive,

published in 1830 to 1842. The first chapter presents his highly

influential characterization of the evolution of science as passing

through three stages. "In the theological

state, the human mind, seeking the essential nature of

beings, the first and final causes (the origin and purpose) of all

effects—in short, absolute knowledge—supposes all phenomena to be

produced by the immediate action of supernatural beings.

In the metaphysical state, which is only a modification of the first, the mind supposes, instead of supernatural beings, abstract forces, veritable entities (that is, personified abstractions) inherent in all beings, and capable of producing all phenomena. What is called the explanation of phenomena is, in this stage, a mere reference of each to its proper entity. In the final, the positive state, the mind has given over the vain search after absolute notions, the origin and destination of the universe, and the causes of phenomena, and applies itself to the study of their laws—that is, their invariable relations of succession and resemblance. Reasoning and observation, duly combined, are the means of this knowledge. What is now understood when we speak of an explanation of facts is simply the establishment of a connection between single phenomena and some general facts, the number of which continually diminishes with the progress of science." p. 26 in Harriet Martineau,(trans.) The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte. Chicago: Belford, Clarke & Co. 1880. |

Auguste Comte |

Comte's analysis provided two ideas that persist over the century to come. The negative idea is that a goal of science is to eliminate something superfluous in science that is broadly characterized as "metaphysics." The positive idea is that the ultimate goal of science is as austere a statement as possible of what phenomena occur with which other phenomena.

| Several later philosophers took up the positivist

tradition. Ernst Mach was, perhaps, the

most important of these as a forerunner of the logical positivist

movement. They formed the "Verein Ernst Mach"--the Ernst Mach

Union--and were its members. Mach himself did not actively label

himself as a positivist, but would accept the name. Mach's positivism was expressed in his idea of science arranging facts in economical order. He wrote in his popular lecture "The Economical Nature of Physical Inquiry." He wrote there: |

Ernst Mach |

|

"… to save the labor of instruction and of

acquisition, concise, abridged description is sought. This is

really all that natural laws are. Knowing the value of the

acceleration of gravity, and Galileo's laws of descent, we possess

simple and compendious directions for reproducing in thought all

possible motions of falling bodies. A formula of this kind is a

complete substitute for a full table of motions of descent,

because by means of the formula the data of such a table can be

easily constructed at a moment's notice without the least

burdening of the memory."

p.193 in Ernst Mach, Popular Scientific Lectures. Trans. T. J. McCormack. Chicago: Open Court. 1898. That is, Galileo noted that, on many occasions, the distance a body fell in times 1, 2, 3, ... was proportional to the square of these times 1, 4, 9, ... and the incremental distance added each time are the odd numbers 1, 3, 5, ... He then announced his law of fall, that the the distance of fall is proportional to the square of the time. All he was announcing was a compact summary of these experimental results. |

Mach was an immensely popular writer. His Science of Mechanics was a combined historical and philosophical survey of the history of physics. It included a searing denunciation of the Absolutes of Newton's mechanics. His critique impressed Einstein greatly in his younger years.

|

Here is his analysis of Newton's Absolute Time: "When we say a thing A changes with the time, we mean simply that the conditions that determine a thing A depend on the conditions that determine another thing B. The vibrations of a pendulum take place in time when its excursion depends on the position of the earth." This is how we are to think positively of time. When a thing A changes its state from condition 1, to condition 2, etc. all that means is that A's state being in these conditions corresponds to a pendulum or some other process also developing through a sequence of different states. We can now return and ask how Newton's Absolute Time might be understood in this way. We find that it cannot. Thus it has no positive place in science: "This absolute time can be measured by comparison

with no motion; it has therefore neither a practical nor a

scientific value; and no one is justified in saying that he knows

aught about it. It is an idle metaphysical conception."

The last boldface sentence is a celebrated negative verdict. Quotes from pp. 223-34 in Ernst Mach, The Science of Mechanics. Trans. T. J. McCormack. Chicago: Open Court, 1919. |

| The central themes of positivism were picked up and developed in the 1920s by a tradition that came to be known as logical positivism. It added to positivism a serious engagement with the use of the machinery of formal logic. The hope was that formalizing language by its machinery would reduce all disagreement to issues that could be settled by its precise techniques. Its leading figures took Mach as their patron spirit and met in Vienna as the celebrated "Vienna Circle." Its leading members included Hans Hahn, Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath and Friedrich Waismann. A comparable movement developed in Berlin under Hans Reichenbach and used the label "logical empiricism." | For example, imagine that I insist that the latest

sage of my favorite cult is immortal. You disagree and think he is

mortal. We resolve our dispute by finding premises on which we

agree. You might check whether I agree that 1. All men are mortal;

and 2. The sage is a man. If so, then logic forces the conclusion

that 3. The sage is mortal. And if we don't agree on these premises,

we just move things back a step and see what grounds them. The logical structure of arguments can be represented symbolically: 1. If A then B. 2. A. 3. Therefore B. So the hope was that this entire procedure of resolution could be conducted symbolically. |

|

In their 1929 manifesto, the logical positivists

articulated their aggressive program for freeing philosophy and all

discourse from meaningless metaphysics. They explained it as

follows:

"Then it appears that there is a sharp boundary between two kinds of statements. To one belong statements as they are made by empirical science; their meaning can be determined by logical analysis or, more precisely, through reduction to the simplest statements about the empirically given. The other statements, to which belong those cited above, reveal themselves as empty of meaning if one takes them in the way that metaphysicians intend." pp. 306-307 in Hahn, Hans; Neurath, Otto; Carnap, Rudolf (1929) Wissenschaftliche Weltauffassung [by?] der Wiener Kreis. Wien: Artur Wolf Verlag; translated as The scientific conception of the world: [by?] The Vienna Circle. In M. Neurath & R. Cohen (Eds.), Empiricism and Sociology. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1973, pp. 298–318. The manifesto gave only a few examples of ideas that would

produce meaningless statements: |

The instrument that would cleave sense from nonsense was given its standard formulation by Friedrich Waismann in 1930 and then developed by Carnap, Schlick and Neurath. It is the "verifiability principle" according to which:

"The meaning of a proposition is the means of its verification."

where verification is just the demonstration of the proposition's truth.

The first formulation of the principle in this wording is credited to Friedrich Waismann's 1930 "Logical Analysis of the Concept of Probability." Erkenntnis, 1 (1930), pp. 228-48. He wrote (p. 229):

"A statement describes a state of affairs. The state of affairs either exists or it does not exist. There is no middle ground, and therefore there is no transition between true and false. If it cannot be stated in any way if a sentence is true, then the sentence has no meaning at all; for the meaning of a sentence is the method of its verification. [... denn der Sinn eines Satzes ist die Methode seiner Verifikation.]"

| At first, the principle seems to make no sense. How can the meaning of something be a "means," that is, a way of doing something. The meaning of the proposition "There are three marbles in the box," one would think, is just what the proposition says: somewhere there is a box and it has three marbles in it. The means of verification of the proposition is something different. It is whatever technique we may use to locate the box, open it and count up the marbles inside. | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Elaborate_wood_box_Tom_Tanaka.JPG |

One of the famous hoax photos of the Cottingley fairies, taken in 1917. They fooled Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes stories. |

Odd as this definition is, the motivation for it becomes immediately clear if we apply it to the problem cases we've been looking at. Take the proposition "there are exactly three pixies in the mountains." We have seen that there is no means of verifying this. So the verifiability principle immediately gives us a comfortable result. The proposition has no meaning. |

So a more straightforward version of the principle makes this interest in the meaningfulness of propositions directly apparent. It asserts:

A

proposition is meaningful if and only if it is possible

--to verify or falsify it (strong version)

--confirm or disconfirm it (weak version).

The versions of this verifiability principle appears in Alfred J. Ayer, Language Truth and Logic, 2nd ed. Victor Gollantz, 1946, p.9.

To verify or falsify is to demonstrate truth or falsity. Finding that an electron has negative charge falsifies the proposition that all electrons are uncharged. But it does not verify it since it is still possible that other electrons have no charge. To confirm or disconfirm is to display evidence that increases or decreases the probability of the proposition. So the finding of an electron with negative charge confirms to some small degree that all electrons have negative charge.

Public domain image from

http://www.wpclipart.com/tools/hammer/mallet/mallet.png.html

The verifiability principle demonstrated great power to cut off long standing philosophical disputes. Proposition after proposition fail the principle's test. So they are judged meaningless--well disguised forms of babble--and thus no longer worthy of philosophical scrutiny and debate. Here are examples of propositions all beaten to meaninglessness by the cudgel of the verifiability principle.

Reality is spiritual.

The moral rightness of an action is a non-empirical property.

Beauty is significant form.

God created the world for the fulfillment of his purpose.

(These from p. Edwards, ed, Encyclopedia

of Philosophy. Vol. 8. MacMIllan, 1967, p. 240.)

Rudolf Carnap provided many more examples of the idle metaphysics that the verifiability principle would not purge from meaningful discourse. For example:

Just like the examined examples “principle” and “God,” most of the other specifically metaphysical terms are devoid of meaning, e.g. “the Idea,” “the Absolute,” “the Unconditioned,” “the Infinite,” “the being of being,” “non-being,” “thing in itself,” “absolute spirit,” “objective spirit,” “essence,” “being-in-itself,” “being-in-and-for-itself,” “emanation,” “manifestation,” “articulation,” “the Ego,” “the non-Ego,” etc.

p. 67 in Carnap, Rudolf (1931) “Ueberwindung der Metaphysik durch logische Analyse der Sprache,” Erkenntnis, Vol. 2 (1931), pp. 219-241; Trans. A. Pap as “The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language,” pp. 61-81 in A. J. Ayer, ed., Logical Positivism. New York: Free Press.

More striking is a passage that Carnap extracted from Heidegger’s Was Ist Metaphysik? [What is Metaphysics?] (p. 69)

“What is to be investigated is being only and—nothing else; being alone and further—nothing; solely being, and beyond being— nothing. What about this Nothing? … Does the Nothing exist only because the Not, i.e. the Negation, exists? Or is it the other way around? Does Negation and the Not exist only because the Nothing exists? … We assert: the Nothing is prior to the Not and the Negation. … Where do we seek the Nothing? How do we find the Nothing. … We know the Nothing. … Anxiety reveals the Nothing. … That for which and because of which we were anxious, was 'really'—nothing. Indeed: the Nothing itself—as such—was present. … What about this Nothing?—The Nothing itself nothings.”

Against this background, one can see immediately why Reichenbach could mount such enthusiasm for Einstein's work in special relativity. Typical applications of the verifiability principle are located in long standing philosophical debates. But here is Einstein using reasoning in a signal scientific breakthrough that looks just the same.

Take the proposition: there is an ether with a unique state of rest. What Einstein found in developing his special theory of relativity was that no observation could distinguish it. So Einstein banished it from physics--and, Reichenbach in effect notes--with essentially the same reasoning as led the logical positivists to discard the spirituality of reality and life forces.

|

For completeness, we should note that Reichenbach

did not see himself as perfectly aligned with the logical

positivists of the Vienna Circle. Reichenbach

was eager to place probabilistic notions at the center of

his analysis. Carnap, however, in this early period of the 1930s,

resisted the intrusion of probabilistic notions. In response,

Reichenbach formulated his own probabilistic version of the

verifiability principle. Here is its first principle:

"First principle of the probability theory of meaning: a proposition has meaning if it is possible to determine a weight, i.e., a degree of probability, for the proposition." p. 54 in Hans Reichenbach, Experience and Prediction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1938. First Phoenix edition, 1961. |

Some of you may notice notice a similarity with these

ideas and Karl Popper's celebrated analysis

of what it is to be scientific. While Popper energetically defended his

priority and creativity, it is not hard to see that his formulation is a

minor variation of the logical positivists' views. Where they say to be meaningful

is to be verifiable or

falsifiable, Popper says that to be scientific

is to be falsifiable. In

retrospect, these are real but small differences that only a true zealot

could muster the energy to debate fiercely. Whereas one seeks to

distinguish meaningful statements and the other scientific statements, the

methods they are using are very close.

For a sober appraisal of Popper's efforts to find an account of the

rationality of science without inductive inference, see my "The

Rise and Fall of Karl Popper's Anti-inductivism."

There is a lot that is right

in this approach. Einstein found a circumstance in which something was

claimed to exist (an ether state of rest) while at the same time our best

theories predicted that we could never detect it. Such a circumstance

ought to be troubling and signal to us that something has gone seriously

awry in our theorizing. We have created a physical notion that is by

construction shielded from all possibility of physical test.

However I also believe that the verificationists went too far. They urged not just that the proposal for things like the ether state of rest was defective. They urged that it was meaningless. That goes too far. The proposition "There is an ether state of rest." is judged by them to be meaningless blather, cognitively equivalent to a grunt or a drool. Surely the proposition is perfectly meaningful--we understand just what it says and presumably so did Einstein. The problem, as I suggested above, is that we have no good reason to believe it. Our best judgment would be to say it is probably false.

By recognizing that the meanings of all concepts are fixed solely by the operations needed to verify them, we avoid smuggling arbitrary preconceptions into our conceptual systems that may prevent us learning new things from experience.

|

Percy William Bridgman (1882-1961) was a Nobel prize winning, experimental physicist who also wrote about scientific methodology, especially in his 1927 Logic of Modern Physics. He believed that one could learn an important moral about the nature of concepts in scientific theories by attending to what Einstein did. Here is his review of what Einstein did and the morals we should draw from them. |  |

| What Einstein did | Bridgman's moral |

| Einstein learned the principle of relativity and the light postulate. | New experience is always possible |

| Einstein could not initially accept them. They appeared irreconcilable because of Einstein's tacit, but erroneous, presumption of absolute simultaneity. | We may not be able to accommodate new experience in our conceptual system because of false presumptions hidden in it. |

| Einstein defined the concept of simultaneity through operations with light signals and revealed the falsity of the presumption of absolute simultaneity. | If we define all our concepts operationally, we purge our conceptual system of harmful, false assumptions. |

| Einstein's revised concepts of space and time are now able to accept new experiences, including relativistic length contraction and time dilation. | Our conceptual

system is now prepared for new experiences. |

In sum, Bridgman's goal was to revise our system of concepts so that we might never again face a revolution triggered by concepts that had false presumptions buried in them. Had we realized that different operations are used to measure the length of moving bodies and the length of resting bodies, we might have been prepared for the possibility that the two might not be the same. He proclaimed:

A very young Einstein. |

"We must

remain aware of these joints in our conceptual system if we hope to

render unnecessary the services of the unborn Einsteins." |

Bridgman used the length of a rod as a way of illustrating his basic idea. Before operationalism, we just talked of the length of a rod, assuming that there is just one length for it. So we were ill-prepared to learn that moving rods have a length different from rods at rest.

Bridgman presumed that a concept was meaningful just up to the operations used to determine it. That meant that if different operations were used, one had different concepts. So we might measure lengths by repeatedly laying out of rulers; that would give one notion of length--call it the "ruler length." Or we might measure length by an operation that times light signals; that would give another notion--call it "light length."

We saw the issues Bridgman had in mind in an earlier chapter when we looked at the problem of the car in a garage.

We measure the length of a car at rest merely by aligning it with the garage and noticing that they match in length.

However, if the car is moving, we needed to devise a more elaborate procedure. In our case, we planted flags simultanenously on the road at the front and rear of the car as it passed by. In a second step, we measured the distance between the flags to recover the length of the moving car.

This procedure then allowed for the possibility that the car driver could

disagree with our length measurement. For the

car driver would not agree with our judgment of simultaneity.

Had we attended to the operations used to measure the length of a car or a rod, we would have realized that different operations are used to measure their lengths at rest and when they are moving. That means they are different concepts and, in principle, may have different values. With that recognition, we are prepared for the possibility of different values, which turns out to be the possibility relativity delivers.

Bridgman formulated his operationism is a way similar to the verificationists. His central claim was:

"In general, we mean by any concept nothing more than a set of operations; the concept is synonymous with the corresponding set of operations."

It does seem peculiar to say that a concept is a set of operations and the idea does not seem very attractive now. What made it attractive to Bridgman is that it immediately gave him the results he wanted. If two quantities are measured by different operations, then their concepts are automatically different. And if we have a quantity, such as our velocity through the ether, that no operation can measure, then there is no physical basis for concept. It is an illicit concept as far as proper physical theorizing is concerned.

Once again there is something right

and important in Bridgman's ideas. If we have a concept, especially a

quantitative one, but no clear idea of the operations needed to fix it or

its magnitude, we may have something defective in our concept. This is a

warning that must be heeded.

What is wrong about Bridgman's system is that it is too

strict. We may well avoid being surprised again by a false

assumption buried in some concept if we become operationists. But, as

Hempel pointed out, the cost will be that science becomes unworkable.

Every distinct operation will yield a new concept. Even rest length would

cease to be single concept; there would be as many variants as ways we can

devise to measure it: ruler length, light length, ruler length measured on

Wednesdays; ruler length with steel rulers; ruler length with brass

rulers; etc. Our theories would need to leave open the question as

to whether each of these are the same.

For better or worse, a workable science must presume, even if provisionally, that the different operations are measuring the same concept.

Image sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Galileo_Thermometer_24_degrees.jpg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Clinical_thermometer_38.7.JPG

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Backofenthermometer.jpg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Irthermo.png

Einstein's rejection of Lorentz's ether based electrodynamics in favor of a novel theory of space and time is a paradigm example of the appropriate use of evidence.

The simplest form of this idea has already been developed in the context of the verificationist moral. Objects moving and at rest in the ether differed in their relation to the ether state of rest. But it was a difference that made no difference. So we had good reason to believe that there really was no difference.

That is, the invisibility of the ether state of rest is simply good evidence that there is no ether state of rest.

Recent work has brought to light a stronger way of understanding how Einstein used what he found as evidence. Recall the difference between Einstein and Lorentz' theories:

| Lorentz | Einstein |

| There is an ether state of rest, but all matter shrinks, all processes slow, etc., so as to make it invisible. Every theory of matter must predict these processes to assure this invisibility. | Space and time are such that lengths shrink and clocks slow with motion. Every theory of matter must predict this since every theory of matter is about substances that reside in the one space and time. |

Maxwell's electrodynamics predicts the length contraction, time dilation and other effects in just the right amounts as to make motion with respect to the ether state of rest invisible. This is defensible in so far as the computations rely on the electrodynamic theory that was already well worked out in 1905. It was a consequence of that theory and one that a defender of an ether theory could well argue was not built into the theory in advance. It was no contrivance but was discovered within the theory.

There was a complication. It was already apparent in Lorentz's time that electrdynamics could not be the only matter theory. Lorentz's electrons consisted of spheres of like electric charges. Each part of one of these spheres repelled the like charges in all the other parts. The sphere would blow itself apart unless there were other non-electrodynamic forces to counteract the repulsions.

To preserve the fit of his theory with failed ether drift experiments, Lorentz had to posit that all these other matter theories would also predict length contractions, time dilations and other effects that would also cancel out any detectible effect of motion through the ether. Since Lorentz could say little about these other matter theories, he was proposing an extraordinary coincidence: that all these other theories just happen to conspire in a way to make the ether state of rest invisible. Here is a depiction of clocks and rods governed by three different matter theories, all manifesting the same contraction and dilation effects.

Einstein's theory requires no such coincidence. Space and time are the way they are--as described in relativity theory. That explains why every theory of matter must predict these effects.

So Einstein's theory explains better because it posits fewer arbitrary coincidences and therefore is better supported by the evidence of these effects. To use a notion pioneered by Wes Salmon, we might may that the spacetime is the single, common cause of these effects in all matter theories. Or, to use the expression preferred by Michel Janssen, who has developed these ideas, Einstein displayed a common origin for all these effects. So he calls the related inferences "COIs"--common origin inferences.

That we find common origins to explain better and so to be better supported by evidence is really a commonplace. Imagine that there is suddenly a series of burglaries in an otherwise quiet street. We are much more likely to infer to a common cause--one burglar robbing repeatedly--than to many independent causes--many burglars who by chance all happen to be robbing at the same time.

| Another illustration is closer to the case of

special relativity. Imagine a darkened hallway.

We notice that everyone walking down the hallway, from either

direction, stumbles at the same place in the dark. We could give a

"Lorentzian" explanation that every person is somehow constituted so

that they all happen to stumble at exactly this same spot. This

makes the stumbling into an unexplained coincidence. Or we could give a "Einsteinian" explanation that there is a fold in the carpet and that everyone trips over just this one fold in the dark. Then the people become probes of the surface of the hall, just as matter probes the background structure of spacetime. The probes all report that there is something to trip over at the same place in the hall, just as all matter reports a Minkowskian structure for spacetime. |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Royal_York_Hallway.JPG |

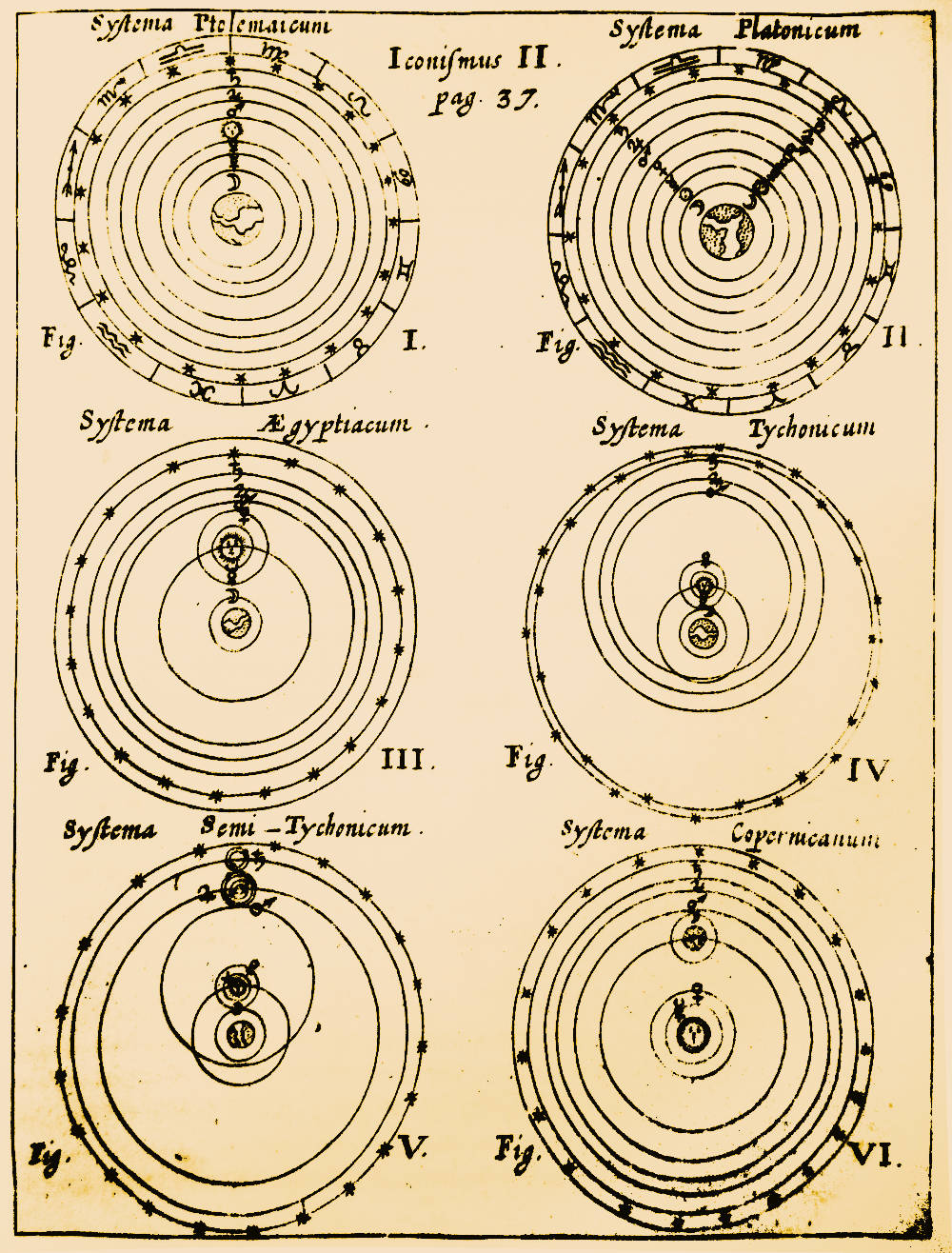

| These inferences also appear throughout science. A famous example is Copernicus' inference that the earth moves. He noted that the motion of the outer planets, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, when viewed from the earth, each had a wobble superimposed upon them. What was curious about the wobbles was that they were perfectly synchronized with each other and also the motion we see for the sun around the earth. He inferred that the apparently coincidental synchronization of the wobble has a common origin. The earth was really moving around the sun and the wobble was merely the superimposition of our motion on the planets. | The situation is not so different from what someone on a pogo stick might see. Everything around them is jumping up and down in synchronized bounces. Of course all they are really seeing is the superimposition of their own bouncing on the things around them. |

Einstein was helped in formulating his special theory of relativity by the distinction between "principle theories" and "constructive theories." The distinction has general applicability as an aid in helping us discover new physical theories.

In the final stages of the years of work that led to the special theory of relativity, Einstein's efforts were advanced decisively when he decided to drop the search for a theory of electrodynamics from which all the processes of electrodynamics could be constructed. In its place he sought a theory whose content would merely be circumscribed by two principles. This reorientation is described in an earlier chapter.

The distinction became prominent in 1919 when Einstein included it in a short summary of the theory of relativity, commissioned by the venerable London newspaper, The Times. His "What is the Theory of Relativity" appeared in the November 29, 1919 issue for reasons tied to important events in Einstein's life. A prediction of Einstein's general theory of relativity is that starlight grazing the sun is deflected very slightly, but by an amount, measurable during a solar eclipse, as described here. In 1919, British astronomical expeditions had confirmed the effect to great hooplah in the press. Einstein was transformed from mere expert in a tiny physics community to a figure in the popular press. The Times commissioned a piece from Einstein in order to slake the popular thirst for information on Einstein's theories.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artillery_of_World_War_I#/media/File:18pounders3rdYpres1917.jpg The concluding paragraph of Einstein's article reveals that he was not a disengaged intellectual, innocent of the practicalities of politics: "Some of the statements in your paper concerning my life and person

owe their origin to the lively imagination of the writer. Here is

yet another application of the principle of relativity for the

delectation of the reader: today I am described in Germany as a

"German savant," and in England as a "Swiss Jew." Should it ever be

my fate to be represented as a bete noire, I should, on

the contrary, become a "Swiss Jew" for the Germans and a "German

savant" for the English." |

The moment was difficult for German-British

relations. For the two had just been engaged in the bitter battles

of the "Great War," which we now call "World War I." It was time for

the two nations to exchange something other than artillery shells.

Einstein had opposed the war. His opening

sentences reflected his relief that relations were

returning the normal. "After the lamentable breakdown of the old active intercourse

between men of learning, I welcome this opportunity of expressing my

feelings of joy and gratitude toward the astronomers and physicists

of England. It is thoroughly in keeping with the great and proud traditions of scientific work in your country that eminent scientists should have spent much time and trouble, and your scientific institutions have spared no expense, to test the implications of a theory which was perfected and published during the war in the land of your enemies. Even though the investigation of the influence of the gravitational field of the sun on light rays is a purely objective matter, I cannot forbear to express my personal thanks to my English colleagues for their work; for without it I could hardly have lived to see the most important implication of my theory tested." |

The distinction between the two types of theories is articulated quite clearly in Einstein's Times article. I will let Einstein speak for himself. He wrote:

| "We can distinguish various kinds of theories in physics. Most of them are constructive. They attempt to build up a picture of the more complex phenomena out of the materials of a relatively simple formal scheme from which they start out. Thus the kinetic theory of gases seeks to reduce mechanical, thermal, and diffusional processes to movements of molecules--i.e., to build them up out of the hypothesis of molecular motion. When we say that we have succeeded in understanding a group of natural processes, we invariably mean that a constructive theory has been found which covers the processes in question." |  |

This was then contrasted with an alternative. Einstein continued:

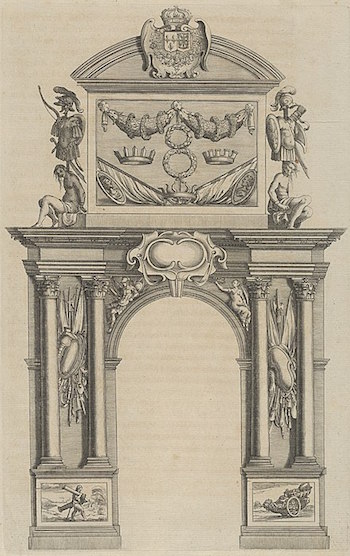

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Triumphal_arch,_ from_%27Éloges_et_discours_sur_la_triomphante_réception_ du_Roy_en_sa_ville_de_Paris_...%27_by_Jean-Baptiste_de_Machault_MET_DP855542.jpg |

"Along with this most important class of theories there exists a second, which I will call 'principle-theories.' These employ the analytic, not the synthetic, method. The elements which form their basis and starting-point are not hypothetically constructed but empirically discovered ones, general characteristics of natural processes, principles that give rise to mathematically formulated criteria which the separate processes or the theoretical representations of them have to satisfy. Thus the science of thermodynamics seeks by analytical means to deduce necessary conditions, which separate events have to satisfy, from the universally experienced fact that perpetual motion is impossible. The advantages of the constructive theory are completeness, adaptability, and clearness, those of the principle theory are logical perfection and security of the foundations." |

Einstein's preferred example of a principle theory is thermodynamics.

It is a very robust theory. The most important principles are its first

and second laws. They assert the conservation of energy and that entropy

cannot decrease. They have broad application. Any thermal system is

subject to these principles.

The distinction between principle and constructive theories is recalled from time to time when modern theorists struggle to develop new theories. The invocation is usually speculative. The hope is that what helped Einstein so much in 1905 might help the modern theorist. Einstein's situation then was that he needed to sweep away a lot of the cluttering details of the electrodynamics in order to expose the new kinematics of special relativity hidden behind it. Might we find ourselves again in the same situation?

While I cannot know what will happen, I am not sure that the distinction has brought any new successes comparable to Einstein's discovery of special relativity. However the pursuit of principles can give an illusion of certainty that goes beyond what is warranted. If one can emulate Einstein and clear the clutter with a decisive principle, then much is gained. If however the principle is a speculation that has unclear content and poor foundation, then the name "principle" can misdirect our understanding.

One example, to be sketched in a later chapter, is

striking. The subsequent development of relativity theory was immersed in

the positing of principles: a generalized

principle of relativity, the principle of general covariance, the

principle of equivalence and Mach's principle. In retrospect, these

principles have served more to obscure the real foundations of the general

theory of relativity than to illuminate them.

For elaboration, see the later chapter "The

Relativity of Accelerated Motion."

| See for example my "All Shook Up: Fluctuations, Maxwell's Demon and the Thermodynamics of Computation" Entropy 2013, 15, 4432-4483. | For an example outside spacetime theories, see my critique of Landauer's principle in the context of thermodynamics and computation. |

Copyright John D. Norton. February 2001;

October 2002; July 2006; February 2, 13, September, 23, 2008; February

1, 2010; January 11, February 2, 2013; February 4, 2015. February 5, 9,

2017. October 20, 2019. April 17, 2020. January 29, 2022. February 10,

August 14, September 23, 2024.