| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

This chapter continues the

discussion of the last chapters on morals that we might try to

draw from special relativity. This chapter collects morals pertaining to

time.

The following

chapter will describe another moral pertaining to time drawn from

special relativity: the thesis of the conventionality of simultaneity.

Several decades ago, this thesis engendered such an energetic discussion

that our presentation here is long enough to require its own chapter.

For a discussion of philosophical

morals that can be drawn from relativity theory concerning space and time,

see my paper, "What

can we Learn about the Ontology of Space and Time from the Theory of

Relativity," on philsci-archive. Beware. The discussion is at a

more advanced level than presumed in this class, so it is only for the

adventurous.

With the transition to relativity theory, we no longer

conduct our physics in a three-dimensional space; we now employ the

four-dimensional spacetime introduced by Minkowski.

| This slogan "time is the fourth dimension" is a mischievous slogan, used, as far as I can tell, to intimidate novices. They are supposed to be awed by the apparent profundity of the claim while at the same time never being able quite to grasp its content at the insightful depth apparently accessible to the mischief making sloganeer. If you meet such a sloganeer, you should ask "what precisely do you mean?" Keep in mind the confusion favored by sloganeers sketched below and insist on a precise answer! | The power of the slogan comes from what it

suggests but does not say. It suggests something like: "In 1903, the

Wright brothers liberated us from the two dimensions of the space of

the earth's surface and opened a new, third dimension, altitude. In

1905, Einstein did it again with a new dimension, time." Spelled out

bluntly like this, the suggestion is obviously nonsense. |

There is no interesting content to the claim. The problem

lies in the vagueness of the statement of the thesis. There are two

readings possible for it and neither yields results of

importance.

In a trivial and true reading, we allow that space and time taken together form a manifold of four dimensions. What that just means is that four numbers are needed to locate an event in spacetime. Three of them are the usual spatial coordinates and the last is a time coordinate. That is true and was always true in classical physics as well. There is nothing of novel interest in this reading beyond the usual banalities about how things change with time. The idea that this sort of spatial representation of time is possible is as old as a pocket book calendar in which the passage of time is represented by a sequence of boxes or list of dates.

There is a profound but false version of the slogan. What if time were a fourth dimension just like the three dimensions of space? That would be extraordinary. It mean that we could move about in the time dimension just as we move about in the space dimension. But time is not just like space in relativity theory. The theory keeps the timelike direction in spacetime quite distinct from the spacelike; the light cone structure does this quite effectively. So relativity theory contradicts this profound reading.

Underlying the profound reading is a simple fallacy. We note that in a spacetime formulation of relativity theory, time is usefully represented spatially in a diagram. So we can infer time must be like space in some aspects or this device would fail. It does not follow that time is like space in all aspects. Analogously, we can represent the spectrum of colors spatially with color wheels and rainbows. That does not mean that colors are spatial. Red is not the fifth dimension of space.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SmallRainbow3483Colours.png

There is an interesting entanglement of space and time in relativity theory captured in the relativity of simultaneity. But the slogan of time as the fourth dimension is a defective and misleading way of expressing it.

Einstein rarely took the trouble to correct misreadings of his work. There were too many of them! However, this misreading of "time is the fourth dimension" as the moral of relativity theory was one that he did pause to correct. In 1946, when he wrote his Autobiographical Notes, he offered the following correction. It says in more restrained terms what I have said above.

Autobiographical Notes, pp. 57-59. |

"First a

remark concerning the relation of the theory to "four-dimensional

space." It is a wide-spread error that the special theory of

relativity is supposed to have, to a certain extent, first

discovered, or at any rate, newly introduced, the

four-dimensionality of the physical continuum. This, of course, is

not the case. Classical mechanics, too, is based on the

four-dimensional continuum of space and time. But in the

four-dimensional continuum of classical physics the subspaces with

constant time value have an absolute reality, independent of the

choice of the reference system. Because of this [fact], the

four-dimensional continuum falls naturally into a three-dimensional

and a one-dimensional (time), so that the four-dimensional point of

view does not force itself upon one as necessary. The

special theory of relativity, on the other hand, creates a formal

dependence between the way in which the spatial co-ordinates, on the

one hand, and the temporal co-ordinates, on the other, have to enter

into the natural laws." |

The relativity of simultaneity establishes that the future is as determinate as the past and present.

This moral is intended to negate a common sense idea we have about the future. It is the idea that the future is unresolved, whereas the present and past are or have happened and are fixed. The notion is captured well enough by comparing who won your favorite sports competition last year with who will win it next year. The winner for last year is known and fixed; it is a part of the determinate past. The winner for next year is open; it is a part of the indeterminate future.

| There was only one past. It is

decided. However many different futures are possible. Which will be

realized is at this moment indeterminate. We popularly imagine that

the moment of the now advances through

history, converting these indeterminate possibilities of the future

into the fixed actualities of the present and the determinate facts

of the past. That there was a rainstorm on February 1 last is a determinate fact. Whether there will be one on February 1 next year in open. It may also be sunny or snowy. Which it is will become a determinate fact when our present has advanced to February 1 next year. |

|

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ, Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line, Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it. |

| This notion of determinateness and indeterminateness will figure prominently in what follows. That is awkward since the notions are not supplied as a theoretical term in special relativity. In the theory, we simply have a spacetime of events. Which are past, present or future depends on where we locate the present moment. Future events are later than present events; past events are earlier than present events. The theory does not tell us where to locate the present and has no physical property that corresponds to determinateness or indeterminateness. The notions are supplied by us externally. | Determinateness and indeterminateness should be distinguished from determinism and indeterminism, where the latter arises in quantum theory. Here's how determinism works. In a deterministic theory, the state of the present fixes the state of the future. That is, at the present moment, the future is determined in the sense that there is only one future possible. But that future has not yet happened, so it remains indeterminate at the present moment. It is determined but indeterminate. The notion of determinism is supplied by the theory; the notion of determinateness is not. |

What is determinateness? A good start is this:

If we conceive of past and present events as fixed and future events as open, determinateness is that property of past and present events that distinguishes them from future events with regard to fixity and openness.

This formulation suggests another version that is closer to the sorts of technical talk that philosophers like:

A event is determinate just in case it is possible, correctly, to assign either of the truth values "true" or "false" to the proposition that it occurs and to the proposition that it does not occur.

Take the proposition: "There will be a rainstorm next February 1." If this future event is indeterminate, then we cannot say of the proposition that it is either true or false. If the future is determinate, then we would be correct to assign a truth value to the proposition, either "true" or "false." We just do not know which is the right one to assign.

| It is sometimes thought that merely

employing a four dimensional spacetime in physics is

already enough to overturn the idea that the future is

indeterminate. For in a spacetime diagram, we see past, present and

future laid out as equally real. This argument is flawed. It depends

essentially on confusing the reality of a picture of a thing with

the reality of the thing. My diary has equally real squares in it

for yesterday and tomorrow. We would not infer from that, that

yesterday and tomorrow are equally real (or that they are squares). A second problem with this approach is that it does not draw on something novel in special relativity. It works equally with any theory of time, including Newton's classical theory. So, whatever moral we might get from it, is equally available from classical physics. |

| An interesting development came in the 1960s,

when C. Wim Rietdijk and Hilary Putnam each came up with an argument

that depended essentially on the relativity of

simultaneity in a Minkowski spacetime. The result that they sought to establish differed slightly from the way the result is formulated above. They did not seek to establish the determinateness of the future but something slightly different, as indicated below. The presentation here will continue to present their analysis as an argument for the determinateness of future events since that fits better with what the argument can be used for. |

C. Wim Rietdijk, "A Rigorous Proof of Determinism

Derived from the Special Theory of Relativity", Philosophy of

Science, 33 (1966) pp. 341–344 Hilary Putnam, "Time and Physical Geometry", Journal of Philosophy, 64, (1967) pp. 240–247. |

| Rietdijk sought to

establish that the future is "determined" in the sense that the

doctrine of determinism is true. He wrote (p. 341): "A proof is given that there does not exist an

event, that is not already in the past for some possible distant

observer at the (our) moment that the latter is "now" for us. ...

Therefore, there is determinism, also in micro-physics."

This is a stronger result than merely the determinateness of future events. Determinism adds the condition that something in the present fixes which events will happen in the future. Determinateness just says that the proposition asserting their occurrence has a definite truth value without relating that truth value to present conditions. |

|

|

Putnam sought to

establish that future events are "real." He wrote that his argument established: (p. 246) "... that all future things are real ("things"

here includes "events"), and likewise that all past things are

real, even though they do not exist now."

The difficulty with this formulation is that it is unclear just how to understand "real" in this context. The term has been a subject of massive debate since 1960s in the context of the realism-anti-realism debates in philosophy of science. My sense is that Putnam's essential argument is unaffected if we replace his "real" by "determinate." |

The argument goes as follows. Consider some possible event in our future: will there be a blizzard next February 1? We can always find a position and motion for a possible observer who would in our present, judge next February 1 to be in his present. For that observer, whether or not there is a blizzard here on February 1 is a present fact. It is determinate. Since that is true now of that observer, should we not also assume that the blizzard (or otherwise) of next February 1 is determinate now?

Let us break out the steps of the argument just sketched more carefully. First, we select some event here on earth to be the event "Earth now." We suppose there is a distant spaceship that approaches the earth at high speed. Here is a spacetime diagram that shows the motions of the earth and the spaceship with the hypersurface of simultaneity of the earth indicated.

The hypersurface of simultaneity allows us to determine which event on spaceship's worldline is simultaneous with the event "Earth now." Call it "Spaceship now."

Since the event "Spaceship now" is simultaneous with the event "Earth now" for the earth observers, it is asserted in the argument that the event "Spaceship now" is determinate with respect to the event "Earth now" for the earth observers.

The spaceship has been supposed to be moving very rapidly towards the earth. That is so that the hypersurface of simultaneity of the spaceship will not coincide with that of the earth. Rather it will be configured as shown in the figure below:

This new hypersurface of simultaneity shows that observers on the spaceship will not find the event "Earth now" to be simultaneous with the the event "Spaceship now." Rather they will judge "Spaceship now" to be simultaneous with some later event on the earth's world line. Call it "Earth later."

Since the spaceship observers judge the event "Earth later" to be simultaneous with the event "Spaceship now," by similar reasoning they will judge "Earth later" to be determinate with respect to the event "Spaceship now."

The combined judgments of determinateness are that "Earth later" is determinate with respect to "Spaceship now," which is determinate with respect to "Earth now," as shown:

That is, dropping the intermediate event, we have that the future event "Earth later" is determinate with respect to the present event "Earth now."

One might well suspect that this analysis gives too strong a result and that something is wrong with it. These suspicions are borne out if we present the argument more carefully:

Earth observer:

Event "Spaceship now" is simultaneous

with respect to event "Earth now."

Therefore Event "Spaceship now" is

determinate with respect to event "Earth now."

Spaceship observer:

Event "Earth later" is simultaneous

with respect to event "Spaceship now"

Therefore event "Earth later" is

determinate with respect to event "Spaceship

now."

Combining:

Event "Earth later" is determinate

with respect to event "Earth now."

There are two weaknesses in the argument.

| First, we

are asked to accept that simultaneity and

determinateness go hand in hand. That is, we must accept

that: "Spaceship now" is simultaneous with respect to the event "Earth now." entails that "Spaceship now" is determinate with respect to the event "Earth now." I see no good reason to accept this. The notion of determinateness itself is sufficiently unclear as to leave me uncertain of its connection to simultaneity. |

Here is a reason to resist the connection between simultaneity and determinateness. Determinateness, as it is used in the argument, is an absolute. The event "Earth later" is determinate with respect to the event "Earth now." That is true no matter which frame of reference is the one to which we relate the events. Judgments of simultaneity, however, differ according to the frame of reference in which the judgments are made. |

| Second, it is not clear that

determinateness is transitive.

Transitivity is the property that allows us to chain together

judgments of determinateness as is done in the little argument

above. For example, the "greater than" relation ">" on numbers is transitive. If A>B and B>C, then A>C. Transitivity can fail. It fails for the "is a friend of" relation. We may have A is a friend of B; and B is a friend of C. It does not follow that A is a friend of C. Whether transitivity is admissible for the determinateness relation depends on what "determinate" means. That meaning remains sufficiently vague for a definite conclusion to be elusive. However if the determinateness relation coincides the simultaneity relation, then its transitivity is dubious. For the simultaneity relation, as it appears in the argument, is not transitive. Simultaneity judgments from different observers cannot be chained together. We cannot infer that the events "Earth later" and "Earth now" are simultaneous. Why should it be different with determinateness? |

The transitivity of simultaneity in the argument

fails since we change the frame of reference in which the judgments

of simultaneity are made. A may be simultaneous with B in frame I. and B may be simultaneous with C is frame II. It does not follow that A and C are simultaneous in any frame. The case of A = Earth now, B = Spaceship now and C = Earth later illustrates the failure. |

How serious are the weaknesses? In my view, they are very serious. To resolve them, we need to find some independent basis upon which to judge the properties carried by determinateness, so that we can decide if determinateness coincides with simultaneity and is transitive. Yet, as the earlier discussion showed, determinateness is a notion we supply from outside relativity theory and in a way that its properties are left vague.

The one property that seemed secure is:

Future events are indeterminate with respect to past and present events.

If we conjoin this as an additional premise to the above argument, we end up concluding a contradiction:

Future event "Earth later" is AND is not determinate with respect to present event "Earth now."

If our premises lead us to a contradiction, we know that at least one of them is false and should be rejected. (This is a reductio ad absurdum.) Which should it be? There are three choices:

Simultaneity coincides with determinateness.

Determinateness is transitive.

Future events are indeterminate with respect to past events.

Given our slender grasp on determinateness, I see no

reason to protect either of the first two from rejection. They

entered in the first place as unsubstantiated suppositions.

People who favor the determinateness of the future, however, are likely to

want to keep the first two and reject the third. Absent an independent

characterization of determinateness, that rejection looks like circular

reasoning. The prior commitment to the determinateness of the future is

merely being reasserted.

Einstein defined simultaneity in terms of a light

signaling operation. We can generalize his procedure to define the

nature of time in terms of signaling with any causal process. To say

that "an event P is earlier than an event Q" simply means that it would

be possible for some causal process to pass from P to Q.

Reichenbach here attempted to solve an old problem in philosophy, rather nicely expressed in a lament by Augustine:

"What, then, is time?

If no one asks me, I know:

if I wish to explain it to one that asketh,

I know not."

| This traditional problem is already captured in the dictionary game. You want to know what time is? Look up the definition of time in the dictionary. And then look up the definition of the definition and soon enough you are back at time, in a closed circuit. There seems no, simple, non-circular way to finish the defining sentence "Time is..." | In my Concise Oxford English Dictionary, "time" is defined as "duration"; and "duration" as "continuance in, length of, time." |

Definition of time

Definition of duration

|

Reichenbach's causal theory of time aims to solve this problem. It will complete the "Time is..." sentence with talk of causes. To be more precise, it looks at the time order of events, that is, the notions of earlier and later. Just what does it mean to say that two events are separated in time? Reichenbach's answer is in terms of causal connectibility. |

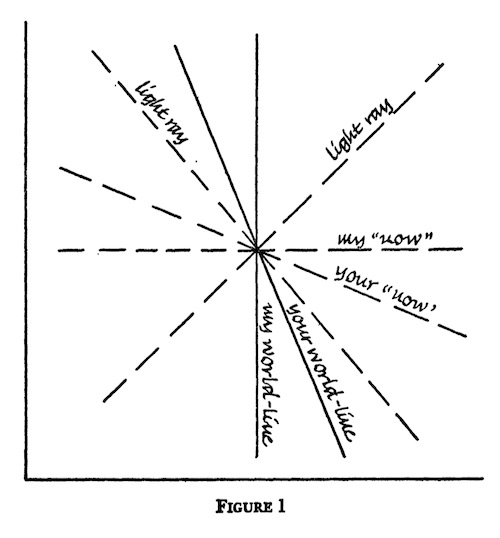

| Here's how Reichenbach

described it in his posthumously published, The

Direction of Time, in the Section "The Causal Theory of

Time," pp. 24-25. "It will be the aim of the present investigation

to show that this [connection between time order and causal

processes] is more than a mere coincidence, that time order is

reducible to causal order. Causal connection is a relation between

physical events and can be formulated in objective terms. If we

define time order in terms of causal connection, we have shown

which specific features of physical reality are reflected in the

structure of time, and we have given an explication of the vague

concept of time order."

Hans Reichenbach, The Direction of Time. Maria Reichenbach, ed., Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971. |

|

Here's the basic definition

underlying the causal theory of time:

| Event P is earlier than event Q | just means that | event P could causally affect event Q

by, for example, the transmission of a light or signal from P to Q. |

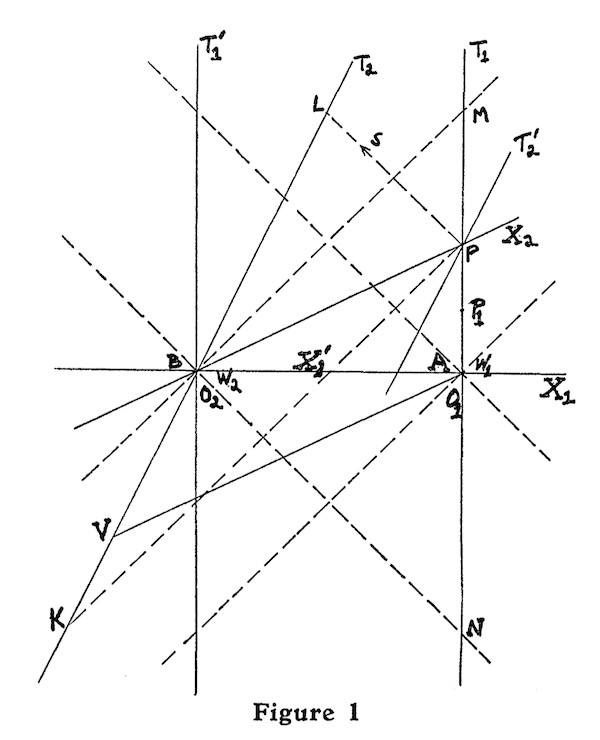

| The inspiration for this approach is

Einstein's 1905 treatment of

simultaneity. In Einstein's special theory of relativity, two events

A and A' are simultaneous if they are hit by light signals emitted

at the same moment from their spatial midpoint; or if light signals

they emit arrive at their spatial midpoint at the same time. The

figure shows the propagation of light signals. Events A and A' are

simultaneous; as are B and B'; and C and C'. Einstein turned this

result into a definition. Two events are defined as simultaneous if

they could be hit by such light signals. A variant form of this

definition was the centerpiece of the first section of Einstein's

paper. The later version of the definition shown here is better suited to Reichenbach's project of reconstructing time from causal relations. The original 1905 version (described in the next chapter) has one light signal traveling from place A to place B and back to A. Einstein's definition required us to identify the event at place A midway in time between the departure and return of the light signal. That event is defined as simultaneous with the reflection event at place B. Identifying that event midway beween departure and return presumes that we have a well-functioning clock at place A, so that it already presumes a notion of temporal passage prior to the operations with light signals. |

Reichenbach extended this thinking to all the time relations between events, being before and being after. It is a truth that P is earlier than Q just if a causal signal could pass from P to Q. Reichenbach now proposed that this truth be a definition.

There is something important

and right about the approach. We cannot allow notions like time to become

too distant from the physical processes of the world. Special relativity

has reminded us that our notions of time must respond to those processes

and the physical theories that govern them. Time is deeply entangled with

causation. We will see just how much more profound that entanglement is

when we deal with the spacetimes of general relativity.

However, in my view, Reichenbach's approach goes too far. We do not just see the entanglement of space and time in his theory. We see the reduction of time order to causal order. Causation becomes the fundamental idea and time order is derived from it. The difficulty is that we end up with a primitive notion, causation, that we seem to understand less well than the thing we started with, time order. So now we must ask "what is causation?" We will have a harder time answering. Theories of the nature of causation remain diverse and controversial. (For my diatribe on causation see "Causation as Folk Science.") Time remains far less problematic; our theories of time are some of the best developed of all physics. A theory that reduces the less problematic to the more problematic seems to me to be most problematic.

Another attempt to understand what time really is, is the so-called "constructive" approach. It is reductive. Reichbach's causal theory of time sought to make the time order of events dependent on causal relations. That is, the time order of events is not fundamentally derived in an independently existing time, but derives from the causal relations between events. The constructive approach is also reductive. Time and space are reduced to properties of matter. The leading idea is that Lorentz got it right in this one aspect in his treatment of length contraction and time dilation. It is offered as an alternative to a realist intermpretation of special relativity. More specifically:

This realist interpretation of special relativity posits the existence of an entity, spacetime. Moving matter in spacetime contracts and its processes slow because they are within spacetime and respond to the temporal and spatial structures of this spacetime.

The constructive alternative follows Lorentz in so far as these contraction and time dilation effects are not attributed to properties of an entity space and time. Rather they arise because of the lawful properties of matter.

We should be clear on how the constructive approach differs from Lorentz's:

For Lorentz, moving bodies contract and their processes slow because they move with respect to the ether frame of reference.

The constructive approach discards the ether frame of rest and says instead:

In the constructive approach, bodies, moving in an inertial frame of reference, contract and their processes slow with respect to those at rest in the inertial frame because of the specific properties of matter.

!!!! NOTE: While Lorentzian in spirit, the constructive approach does not seek to restore an ether state of rest.

|

Harvey Brown is the foremost proponent of a

recent version of constructive relativity, which he distinguishes as

"dynamical relativity." He summarized the view as: "In a nutshell, the idea is to deny that the distinction Einstein made in his 1905 paper between the kinematical and dynamical parts of the discussion is a fundamental one, and to assert that relativistic phenomena like length contraction and time dilation are in the last analysis the result of structural properties of the quantum theory of matter." Harvey R. Brown, Physical Relativity: Space-time Structure from a Dynamical Perspective. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005. pp. vii-viii.  |

An analogy might help to clarify the difference between the realist and constructive views. Consider a large magnet. For science lovers, it is a familiar amusement to explore how this magnet interacts with other small magnets. If we bring a small magnet close to the large one such that their same poles face each other, we feel a resistance to the approach of the small magnet. There seems to be something there, invisible in the space. We can plot out its disposition by moving the small magnet around the pole of the larger one. We can use many different small magnets in the same way and they will each produce the same results.

Someone whose conception is analogous to the spacetime realist would conclude that there is a real but invisible thing there, a magnetic field. The small magnets are merely probes that map out its configuration. The fact that many different probes find the same field is evidence of the independent existence of the field

Someone whose conception is analogous to the constructive relativist would merely conclude that this behavior is evidence of a law of repulsion between like poles of magnets. That there is an invisible thing in the space is merely an illusion. All we known is what we find in the repulsive forces acting on the small magnets. They all give the same results since all the magnets are governed by the same force law.

The difference between the constructive and realist interpretation mirrors the morals concerning theory and evidence of the last chapter.

The verificationist and operationist approached to theory and evidence promote an austere view. They both highlight the danger in proceeding too far from the solid basis of what is directly experienced into an abstracted realm of theory. Correspondingly, the constructivist finds no direct access to a spacetime. All we ever have are the behaviours of rods and clocks. Space and times enter only as properties of the material constituting the rod and clocks.

A more expansive view of the reach of evidence is provided by Janssen's "common origin inferences." That all rods and clocks return the same spatial and temporal results is evidence of a common origin, an independently existing space and time. They are not just matter doing what matter does. They are probes of something not directly visible, an independently existing spacetime, and we can see that they are probes from the fact that all matter theories return the same spatial and temporal results.

The constructivist response is that the agreement of all matter theories is no evidence that they are probing an independently existing spacetime structure, but merely a brute fact about all matter theories. That means that is a fact that is not in need of any further explanation. It just is so. Here is Brown's (p. 143) formulation, expressed in terms of the Lorentz covariance of matter theories, which is the property that enforces relativistic behavior on the matter of the theory:

In the dynamical approach to length contraction and time dilation that was outlined in the previous chapter, the Lorentz covariance of all the fundamental laws of physics is an unexplained brute fact."

My view? I think the agreement in matter theories does mean we should interpret them as probes. They provide evidence for an independently existing spacetime. Further, I have argued that the constructive approach must covertly presuppose a list of commitments equivalent to the realist's if the constructive approach is to return an empirically adequate theory. See "Why Constructive Relativity Fails," British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 59 (2008), pp. 821-834.

Among the candidate morals of this and the last two

chapters, everyone will find their own favorites, although it can be quite

hard to make the selection. For what it is worth, here are my picks. They

have actually mostly been embedded in the earlier critical discussion.

Common sense tracks the

latest science. That is, common sense lags behind our latest

science, which is very slowly incorporated into that nebulous "what

everyone knows." Doesn't everyone now know that matter is made of atoms;

or that the air is part oxygen and that oxygen is the bit that matters for

our survival? Yet all this was once the most advanced science. The process

seems to be continuing with special relativity. Many people somehow know

that "nothing goes faster than light" but they are not sure where is comes

from. The moral is not solely derived from special relativity, but special

relativity does supply a nice instance of it.

Mature theories are very

stable in the domains for which they were devised. They are fragile

elsewhere. This is what I think should be learned from the long

history of fragility of scientific theories, with the advent of special

relativity an excellent example. While theories do not retain unqualified

validity when we move to new domains, the mature theories remain

essentially unaltered in their original domains. We need relativity theory

for motions close to the speed light, yet we still use ordinary Newtonian

theory for motions at ordinary speed. That does not seem likely to change.

Beware of theories or parts

of theories that are designed to escape experimental or observational

test. This is the part the verificationists got right. There is

something very fishy about theoretical entities with properties so

perfectly contrived that we cannot ever put them to observational or

theoretical test. We should treat them with the highest suspicion. Asking

for the means of verification or falsification is a good test if one is

suspicious. Finding clear conditions for verification or falsification is

an assurance that a healthy connection between the theory and experience

is possible.

Be ready to abandon concepts that hide empirical content. This is the part that the operationists got right. One cannot develop conceptual schemes without making presumptions about the world, yet those very presumptions can be contradicted by emerging science, making acceptance or even formulation of appropriate new theories difficult. A related concern is that some concepts may have no real basis in experience at all (e.g. ether state of rest!). Asking for an operational definition of the concept is a healthy but not final test. If it admits an operational definition, then at least we know it has a connection to possible experience.

Infer

to common causes. When you have the choice, the better

explanation is the one that posits fewer coincidences and that is the one

you should infer to.

Space isolates us causally.

The novel results about space and time itself provide some of the most

interesting results of special relativity. If we try to look beyond the

theory and still have outcomes that pertain to space and time, I think the

most important is simply the idea of upper limit of speed of light to

causal interactions. That tells us that we are quite powerfully causally

isolated from other parts of the universe. Nearby galaxies are already millions

of light years away. That means that just sending a signal from our galaxy

to another will require eons of time. Conversely, something happening

there now will not affect us for the corresponding eons.

If one wishes to press further, special relativity has revealed a

relatedness of space and time that we did not formerly suspect. It is hard

to know how best to express this entanglement. I think the best way is

still our familiar relativity of simultaneity.

Copyright John D. Norton. February 2001; October 2002; July 2006; February 2, 13, September, 23, 2008; February 1, 2010; February 11, 2013. February 9, 2017; October 1, 2019. Section renumbering, October 20, 2019. September 22, 2020. February 10, 2022. February 10, September 25, 2024.