| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |review |

|

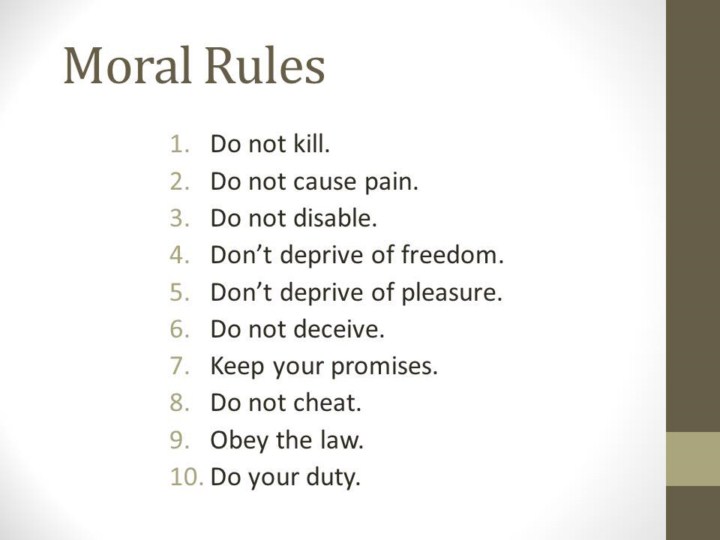

These are the ten rules of the common morality. There may be other formulations of them that prohibit and require the same kinds of acts, but I like this formulation because it conforms to my tradition. It has 10 rules, divided into two tablets of five each. None of these rules should be surprising to you, for all of you use these rules or their equivalents in making your moral decisions and judgments. You will note the non-accidental coincidence between what the first five rules prohibit and the five harms that I presented in the second slide. This is because morality is the system rational people put forward to govern the behavior of all those with whom they interact. The second five rules are also related to these five harms, although not every violation of the second five rules leads to someone suffering harm. However, violation of any of the second five rules increases the risk of someone suffering some harm and the more widespread are violations of the second five rules, the more harm will be suffered. Because not every violation of the second five rules causes harm, it is with regard to these rules that even well intentioned people sometimes ask, “Why should I be moral?” This is where it is important to recognize that morality is for fallible biased people. Failure to realize this is what is responsible for many of the weird views about morality that have been put forward by philosophers. The only weird view that I will mention is what is known as act utilitarianism or act consequentialism. I mention this view because it is a view that initially sounds very plausible and that many people claim to accept because they fail to realize that morality governs behavior between fallible biased beings. Morality is not for impartial omniscient beings. Taking act utilitarianism or act consequentialism as a moral guide would require people to do that act which they regard as having the best overall consequences, that is, what they regard the best balance of less harms and more benefits than any other act. (Of course, other people may have a different view of what counts as the best overall consequences.) On this view, moral rules have no significance, people should simply act to achieve the best consequences and pay no attention to whether their actions involve deception, breaking a promise, cheating, disobeying a law or neglecting their duty. Just imagine what life would be like if everyone did what they thought was best and paid no attention to whether they were violating any of the moral rules. It would be a disaster. That we regard the rules as important is shown by the fact that we have common moral virtues that are related to each of the second five rules, e.g., truthful, trustworthy, and fair. There are no virtues related to the first five rules, everyone is simply expected to obey them. Although it is important to use these rules as moral guides, it would be disastrous to regard them as absolute, that is, to hold that it is always immoral to break any of these rules no matter what the circumstances were. This applies to the first five rules as well as the second five. Neither ignoring the rules nor taking them as absolute is acceptable. |