XI. 1893

The three-year period following the Great Johnstown Flood saw the Johnson Company rise to its apex as an independent business enterprise. It had so completely seized control of the street railway track work market that its name was virtually synonymous with the track work of electric street railways all across the country. Over the period, it had supplied track materials to most of the existing railway companies and its Electrical Department had begun installation of lines using a newly-developed continuous welding process. Moreover, the company had expanded into all dimensions of the street railway business as well, producing single and double trucks, regular and special purpose car bodies, and electric motors, all in Tom Johnson's railway shops in Cleveland. When the General Electric Company was formed by the merger of Edison Electric, Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company, and Thomson-Houston in 1892, Tom Johnson feared that General Electric and its main competitor Westinghouse would control the electric motor market. He therefore moved quickly to charter his own motor works, the Steel Motor Company, making it independent of his railway company.

The speed with which the Johnson Company grew was also remarkable. Since 1886, the company had built and then been forced to expand two large mills, the switch works in Woodvale and the rail mill and foundries south of Johnstown in the town of Moxham. In just the three-year period following the Great Flood, the company's net profits exceeded $2.1 million. On a capital investment of $2.75 million, an average of $528,000 in annual dividends was paid out to its private stockholders, principally Tom Johnson and Fred du Pont. By 1893, the company had made Johnson, Moxham, and du Pont very wealthy men. While du Pont had been one of the wealthiest men in Louisville for several decades, such wealth was new to Johnson and Moxham. The Jaybird had brought them very far indeed.

The year 1893 proved to be a watershed for most railroad, industrial, and banking enterprises, and for steel rail producers in particular. The steel rail market had blossomed in the late 1860s with the dramatic expansion in railroad construction. A few of the more successful rail mills, including Cambria Iron, had capitalized on the trend by enlarging and integrating their production capacities. As a result, these large integrated mills would come to dominate the rail market for the next thirty years. But when railroad construction slowed in the late 1870s, the overcapacity in steel rail production became more obvious. From the largest integrated plants in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Johnstown, to the many local mills on both sides of the Alleghenies, steel rail producers faced a vastly more competitive market in which profit margins were narrowing markedly.

Fluctuations in steel rail prices, including two precipitous drops in the 1880s, brought profit margins dangerously close to zero, jeopardizing the huge capital investments that had been made in the initial integration period of the early 1870s. While rail orders had risen to fairly high levels in the last quarter of 1891, due primarily to the price of steel rails dropping to an all-time low of $17.99 per long ton, orders fluctuated wildly over the next two years. From a general average of 50-60,000 tons per year through 1892, rail orders dropped to under 20,000 tons a year by the summer of 1894, and averaged only about 30,000 tons per year through 1896.

The drop in rail prices was caused largely by increased competitiveness in the steel rail market, as large producers expanded and integrated and smaller, local producers tried desperately to retain their small shares of the market. Both railroads and steel rail producers had invested heavily in expansion and integration of their operations, and their prosperity depended on continued growth. There were mixed signals as to the health of the national economy in mid-1892, but railroads were declaring strong dividends and other industrial sectors exhibited expansion. The harbinger of ill fortune was to be the declaration of bankruptcy by the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad on February 20, 1893.

Though the cause of the large railroad's financial failure could well have been traced to its own bad management, the sudden insolvency of the Reading send tremors through national financial markets. The realization that a railroad the size of the Reading and financed by several Wall Street firms could be insolvent forced other railroads to reevaluate their plans for expansion and many large investors to reassess their holdings of railroad securities. At the same time, the credit market as a whole was experiencing a contraction because of the steady decline in gold reserves. Understandably, national banking interests became increasingly cautious about their own liquidity. Many watched fearfully as the stock market dropped several times in April, but were momentarily relieved when the market seemed to rally. Later that month, the Pennsylvania Steel Company, one of the smaller rail producers, went into receivership.

Then, on May 3, 1893, the stock market dropped fifteen points, its largest drop since the depression of 1884, and the national credit market began to collapse. The next day, National Cordage went into receivership and three Wall Street brokerage houses failed. Additional stock market drops, financial stringency in national and state banks, and subsequent bank failures or suspensions of cash payments occurred in steady sequence. Most of the national banking failures were in the south and west, where more speculative investing was rampant, and the tide swept up state banks, private banks, and trust and mortgage companies as well. Liquidity problems in these "interior" banks caused them to draw upon their reserves in New York banks, precipitating a liquidity problem throughout the national banking system. The resulting Panic of 1893, as it would be known, lasted through August.

The collapse of the credit market that summer triggered an industrial depression. Between June 1893 and June 1894, 125 railroads went into receivership. By the end of 1894, over 192 railroads were in receivership and most had suspended payments of dividends. And while many heavily capitalized industries, including the production of pig iron, recovered steadily from June 1894 (considered by many the low-point in the depression) through December of 1895, railroads on the whole did not join in the recovery. Most went into receivership and were reorganized, and railroad construction dropped from 4,700 miles in 1892 to a low of 1,800 miles in 1895. Railroad construction continued to be slow through 1897, and would not return to pre-1893 levels until after the turn of the century.

Among the other major sectors in the national economy, the most resilient during this period were those associated with the emerging electrical industry. Investments in electric light and power enterprises grew 450 per cent between 1892 and 1898. Even in the tightly contracted credit market following the Panic, capitalization of electric railways, considered a strong investment opportunity by European investors cautious about industrial securities, quadrupled from $400 million to $1.6 billion by 1900.

Consequently, the Johnson Company was not immediately or directly impacted by either the drop in railroad rail demand or the contraction of the national credit market. For years, the major steel rail producers generally ignored the street rail market as too small to bother with, and smaller rail producers were dissuaded from entering the market by the Johnson patents. The Johnson Company, in effect, controlled both demand and price in its own market. Its two major expansions, in 1887 and after the Flood in 1889, were financed privately (mostly through increased investment by Fred du Pont) and by reinvestment of company profits (after which the company still paid out over 6 % in dividend returns).

The solid liquidity position of the company allowed it to continue to accept orders from street railway companies which often could only back their purchases with bonds rather than cash. Because the Johnson Company could afford to wait until the bonds appreciated in value, which would occur after the construction of the railway lines was completed, it realized an even greater profit from sales than if it had accepted cash payment outright. Particularly after 1893, many railway companies found it difficult to generate a cash position sufficient to place orders for new track work, and would have foregone orders except for Johnson's willingness to accept their bonds instead.

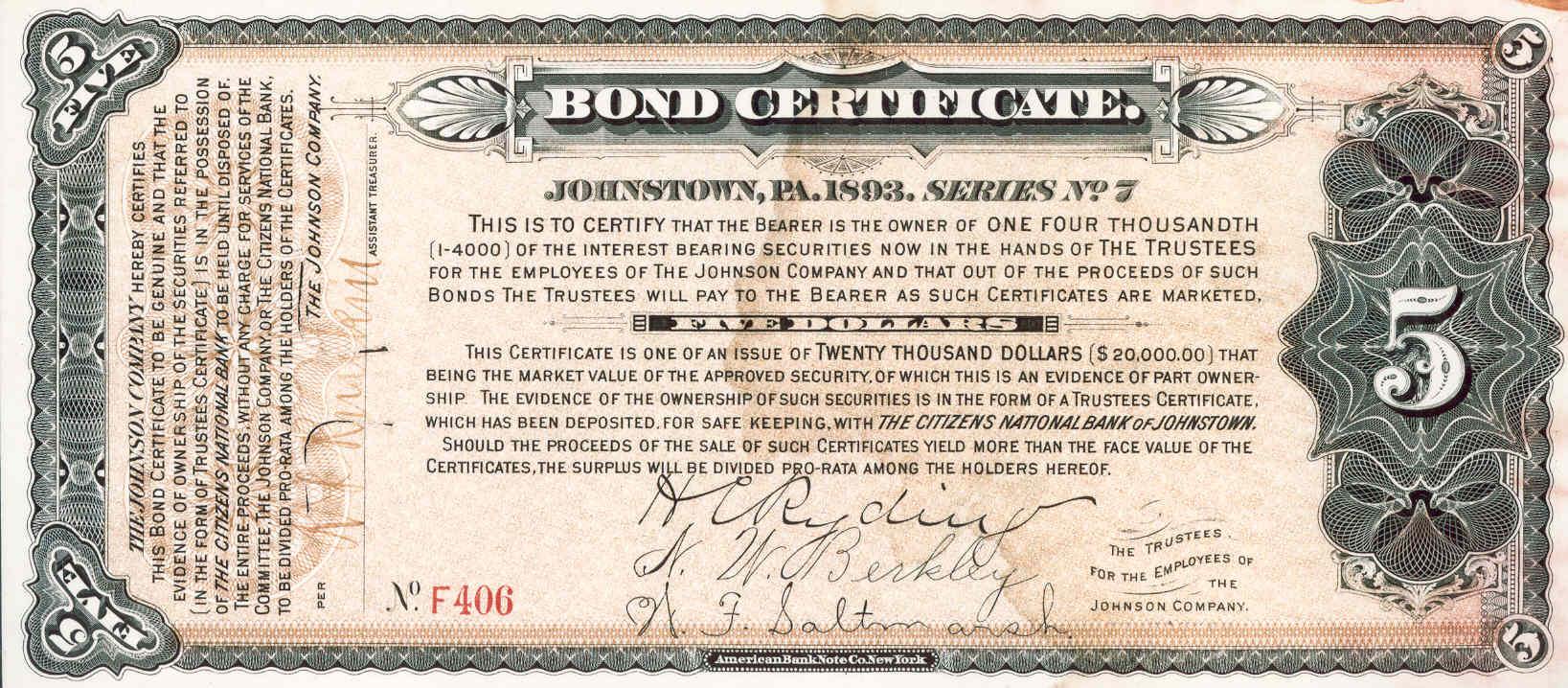

In this manner, the company was able to run its mill and track work operations at near full capacity throughout the depression period while less-liquid fabricators of railroad rail operated at reduced capacity or closed down for lack of cash-backed orders. Johnson was able to maintain its liquidity by persuading its employees to convert their cash wages immediately into company bond certificates drawn on a local bank, certificates which were redeemable at local stores. In effect, employees were paid in promissory notes and the company retained its cash base to finance the practice of accepting bond-backed rail orders.

When rail prices began to drop in the early 1890s, the larger steel producers again formed a rail pool, this time to limit rail production. The move forced several of the smaller, idle rail mills such as Pennsylvania Steel out of the rail market altogether and they in turn attempted to break into the street rail market by replicating several Johnson Company products. In 1891-92, the Johnson Company lost a series of patent infringement cases at the lower court levels, and sustained a major loss on appeal in June 1893 to Tidewater Steel-Works. Though the company's position in its own market was fairly secure, it still depended on the major steelmakers for Bessemer blooms and was therefore vulnerable to the pricing decisions of the members of the rail pool. And while the steel pool was established to control production levels rather than prices, the emergence of a monopoly in production of basic steel was understandably troubling to Moxham.

Already Moxham had experienced production difficulties with the Bessemer blooms acquired from the Cambria Iron and several other Pittsburgh steelmakers. Many blooms would arrive at the mill in odd shapes and inconsistent quality, making rolling more difficult. In earlier years, these manufacturing inconveniences were routinely absorbed as production costs because of the company's extremely high overall profit margin, largely generated by the specialty track work division. By 1893 however, while the track work division remained quite profitable, higher material and manufacturing costs were eroding the profit margin of the rail mill. Moxham's material costs could increase even further if the rail pool attempted to control the price of basic steel.

In terms of production, Moxham had already transformed the rail mill and foundries into highly sophisticated manufacturing facilities. Each unit was skillfully organized, equipped with the best available types of furnaces, and operated by highly trained and experienced personnel. In the rail mill, Moxham had standardized production and improved product quality, and continued to develop new products, machinery and tools, and production processes. He had constructed his own railroad spur for product and materials distribution, and had acquired significant coal deposits in the local area (notably the Ingleside Coal Company) so as to control his plant's supply of fuel. Moreover, the company had successfully expanded into virtually every aspect of the street railway business, including production of rails, track work, cars, trucks, and motors. Through its development (with engineers of Thomson-Houston) of continuous welding techniques, its Electrical Department became an installer of railway systems as well.

The entire operation was backed by a sophisticated distribution and sales organization, staffed by qualified engineers in regional sales offices, and an aggressive defense of the company's extensive patent holdings. The only option remaining open to Moxham, to either secure a profit margin in the rail division or to pursue other product lines, was to produce his own blooms. If he were able to integrate his operations into the production of basic steel, he could not only standardize the shape and metallurgical quality of his blooms, but also eliminate the extensive reheating costs associated with working with cold blooms. As he had discovered in his patented iron making processes in the mid-1870s, blooms formed at the mill could move straight to rolling without heating. Production of basic steel at the rail mill however would require an extensive recapitalization of the company.

Moxham had seriously considered constructing his own blast furnaces and coke ovens as early as 1891, and had already surveyed and obtained some rights-of-way from the rail mill to connect with the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad east of Johnstown at Cambria City. In fact, he had purchased properties in Ferndale to the south of the rail mill as sites for additional sidings. But when it came time to make the decision on expanding the rail mill to include production of basic steel, Moxham had demurred. Well into 1891, he was secure with respect to market and production and could afford to delay increased capitalization as long as the profit margin remained high. By late 1892, however, the company's growth pattern had leveled off and its production costs, particularly in the rail mill, were still rising. Technologically, Moxham had advanced as far as he could with the rail mill. Production of his own basic steel was the only alternative.

Typically, the Johnson Company would draw cash for its additional capital needs from either reinvestment of company profits or from stockholders, primarily Tom Johnson and Fred du Pont. The company was already accepting railway bonds in payment for rail orders and was far less liquid than it had been when it undertook previous expansions of production capacity. This time, the company would have to rely again on Fred du Pont, whose seemingly unlimited sources of capital and unwavering faith in the Johnson Company enterprise had bankrolled the two previous expansions. On May 16, 1893, access to du Pont capital became significantly more complicated.

Fred du Pont was a sixty-year-old bachelor who by many accounts could have been the wealthiest man in Louisville. He owned the First National Bank, the paper mill, the iron and coal mines west of the city, a local railroad, and numerous other enterprises. As charitable contributions, he had recently given the City of Louisville a brand new high school and a large central park, both valued at over $500,000. Unknown to most, he also held among his securities close to $1.3 million in Johnson Company stock and bonds, and an additional $143,000 in stock and bonds in Tom Johnson's Johnstown Passenger Railway Company.

Fred had always led a simple, almost austere life. He had for decades lived in an apartment in the Galt House and involved himself selectively in the operations of his various enterprises in Louisville and Central City. He was well-known but not as highly (and politically) visible as his brother Bidermann, owner of two Louisville papers and the Central Passenger Railway. Disassociated by choice from the Du Pont Powder Company and most of his extended family in Wilmington, Fred still kept in touch with his elderly mother Margaretta and looked after the interests of his nephews Alfred I. du Pont and Pierre S. du Pont, the latter being the eldest of the nine children of his deceased brother Lammot. Fred counted as his own family in Louisville only that of his brother Bidermann, including Bid's eldest son Coleman who had apprenticed at the mines of the Central Coal & Iron Company and become superintendent of the Central City operations by 1888. Also as close as if they were his own sons were the two young lads who had come under his tutelage over twenty years before, Tom Johnson and Arthur Moxham.

Johnson, now living in Cleveland, had advised Fred quite profitably on investments in various street railways (not to mention the Johnson Company) for over ten years, and Fred trusted his intuition and business sense. Fred himself was known to tinker with railway ideas, and some of the trucks turned out by the Johnson's railway companies in Cleveland bore du Pont's name on the patents. Fred saw in young Moxham a man very much like himself, a self-made man who saw work as an end in itself and who had made his own way up the business ladder through individual initiative and drive. It was not surprising that Fred had become a familiar figure in Johnstown as well. He often visited Moxham and delighted in walking through the mill and talking shop with the draftsmen and carpenters about new designs they were working on. Frequently he would represent the company in meetings of local borough councils discussing rights-of-way and track maintenance in their municipalities. It was doubtful however that Johnstowners understood Fred's significance to the Johnson Company beyond the general notion that he was one of the three partners in its operation.

On the morning of May 16th, Fred left the Galt House to visit Maggie Payne several blocks away on West York Street. Maggie was the madam of the most popular bordello in Louisville, and, it was rumored, had given birth to his child for which she was demanding support. In the ensuing argument, Maggie drew out a pistol and shot the old man dead. Fearing scandal, family members in both Louisville and Wilmington portrayed his death as officially caused by a heart attack and pressured local newspapers to confine themselves to eulogizing Fred's generous contributions to the city. The very evening of his death, Fred's body was carried by train to Wilmington, where it was quietly interred in Sand Hole Woods, the du Pont family cemetery.

The estate of Alfred V. du Pont was enormous, and the terms of his will were very precise. Tom Johnson and Coleman du Pont were to serve as co-executors of the estate, valued conservatively at over $2.2 million. Half of the estate went to Fred's mother Margaretta Lammot, with the understanding that, under the wise counsel of Tom Johnson, it would be distributed evenly among his brother Bidermann and his nephews Coleman, Alfred, and Pierre. In addition, Bidermann himself would receive about $115,000 in Johnson Company stock and bonds.

Of the remainder, over $500,000 in securities were to be held in trust by Pierre on behalf of his seven minor brothers and sisters. As a consequence Pierre, at the age of 23, became responsible for overseeing well over $350,000 in Johnson Company securities. And while the du Pont family continued to support the company by holding its securities, the fragmentation of stock and bond holdings among du Pont family members, most of whom were in Wilmington, made company policy a matter of some negotiation. In that negotiation, Pierre S. du Pont was now a major partner.