XII. The Big Gamble

The message seemed quite clear. The Johnson Company had to integrate basic steelmaking into its operations. The Panic of 1893 and the success of the steel pool in limiting rail production had merely pressed Moxham to move more quickly. By late 1893, he began looking in earnest for potential sites to locate his primary mill. Naturally, the Johnstown area was one possibility, but first Moxham had to investigate whether he could negotiate rights-of-way through Johnstown to connect with the Pennsylvania Railroad main line running east and west out of the city. The Pennsylvania however began to drag its feet, and attempting to follow suit, the Johnstown City Council itself began to raise objections in early 1894.

Intense local politiking surrounded Moxham's petitions for rights-of-way through the city. It was widely speculated that the Cambria Iron Company was not enthusiastic about the Johnson Company building blast furnaces and becoming a competitor rather than a consumer of raw steel. Despite the local ruckus, these were not among Moxham's primary concerns. Of far greater significance were the changes that were taking place in basic steelmaking as a national industry. To be competitive in the low-price, low-demand steel market of the early 1890s, a steel manufacturer had to run a cost-efficient mill, reducing costs of materials and labor, and building larger furnaces. It also meant controlling production levels in the industry as a whole, which precipitated the formation of the steel pool in the first place. Older mills had to either expand their furnace capacity or confine their operations to smaller, local markets. Steelmakers building new primary mills had to plan on constructing an entirely integrated operation with huge furnaces. This alone required a fair expanse of land which was at Moxham's present site not readily available.

Of equal concern was the depletion of local ore sources on which most steelmakers had depended for over thirty years. The newly discovered and accessible Great Lakes ore fields offered plentiful supplies of high quality ore for those steelmakers who could gain and retain access to them. Several of the largest steelmakers moved quickly to absorb ore mining and shipping operations by purchasing controlling interest in mining companies, railroad spurs that served them, shipping lines that transported the ore on the Great Lakes, and unloading and transshipment depots on the southern shores of Lakes Michigan and Erie. Location of a new primary mill along the Great Lakes could cut additional transportation costs significantly.

In February of 1894, Moxham surveyed several potential mill sites along the Ohio shore of Lake Erie at Youngstown, Cleveland, and Lorain. He then convened a Johnson Company stockholders meeting on March 6th to ask for an additional $2 million in capital for the construction of an integrated primary and rail mill including blast furnaces and coke ovens. Five weeks later, he confirmed publicly what had been rumored in Johnstown for months. The Johnson Company had purchased six square miles (3,700 acres) of land in Lorain, Ohio at the mouth of the Black River for purposes of building an integrated steel mill, other steel-related industries, and a new residential community. After consulting with Pierre du Pont, the company's major bond holder, Moxham announced in June that he was forming a new company, the Johnson Company of Ohio, with an additional stock issue of $2 million. The rail mill and switch works in Johnstown was to become the Johnson Company of Pennsylvania, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the newly-formed Johnson Company of Ohio.

In a single bold stroke, Moxham shifted not only the geographical location of his operations, but the principal focus of his manufacturing efforts as well. With basic steelmakers moving into the manufacture of finished steel products to gain greater control over market demand and price, the Johnson Company as a simple rail and track work company dependent on the major steelmakers for its basic steel faced certain market isolation. If the company wanted to change its manufacturing line to include other steel products for which there was a growing market (such as structural steel), it had to make its own steel. That would require the development of steelmaking capacity on a competitive level with established steelmakers and access to the Great Lakes ore fields to minimize transportation costs.

Construction on the 700-acre mill site at Lorain began in July 1894. Within four months, the basic mill structure was completed and Moxham started to dismantle the Johnstown rail mill for relocation. The last girder rail was rolled in Johnstown on January 26, 1895. Most of Moxham's key skilled personnel, including management, engineers, foundrymen and roll floor technicians, went to Lorain. The Johnson Company's main offices were moved in March. As with the planning of the Johnstown mill some six years before, Tom Johnson invested heavily in land at the Lorain site as well. In the original Lorain transactions, he purchased over 3,000 acres of land for residential, commercial, and light industrial properties, and formed the Sheffield Land Company to oversee their development and sale. As part of the planned community, Johnson formed the Lorain Street Railway Company and constructed an electric street railway system that connected the mill with Lorain and the other surrounding communities. Like the town of Moxham, Lorain was to grow with the success of the mill.

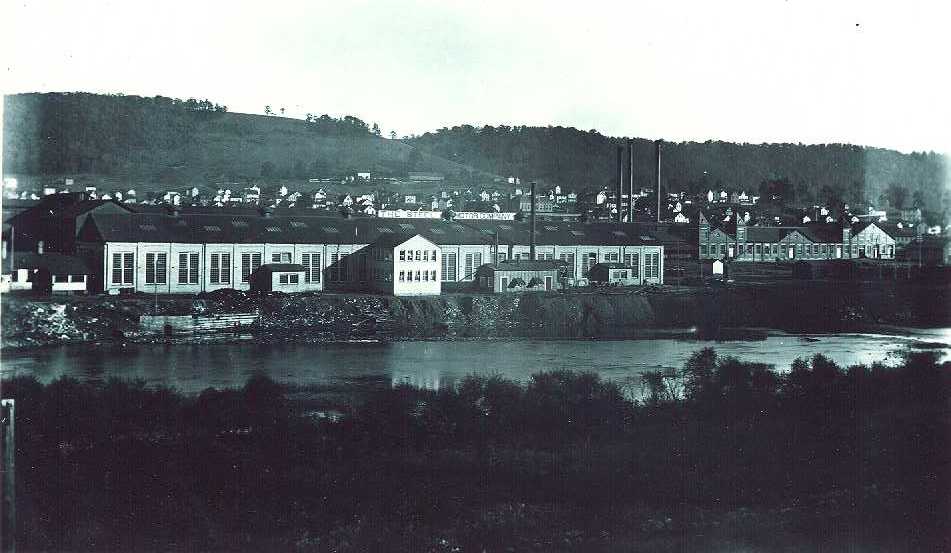

According to Moxham's plan, the mill in Johnstown was to remain primarily a switch works, completing fabrication and foundry work for the company's well-established street railway business. To take advantage of the skilled personnel in Johnstown and to protect their land investments in the town of Moxham, Tom Johnson moved the Steel Motor Company from its Cleveland plant into the huge track welding building at the Johnstown mill site. While this move transferred over 200 jobs back into the Johnstown site, it had little effect on declining property values in Moxham. Too many empty residential properties had been left by Johnson employees when they transferred to Lorain, and few of the relocated Steel Motor workers were confident enough of the company's future to purchase houses in Moxham.

The Johnstown mill was placed under the supervision of Thomas Coleman du Pont, Bidermann du Pont's eldest son. After completing his studies at MIT in 1883, Coleman apprenticed at his father's Central Coal and Iron Company in Central City, Kentucky and rose steadily through the ranks, reaching the position of mine superintendent by 1888. Over the next four years, he was the driving force behind the modernization of Central's mining operations and the transformation of Central City from a one-store town with mud streets to a thriving city. He was by all accounts genuinely popular with both miners and local businessmen, and decided in 1893 to run for mayor of Central City. But the election presented many of the miners with a real conflict of loyalties. After a series of coal strikes and other labor disputes through the late 1880s, management-labor relations were tense at Central Coal and Iron and Coleman was not only part of management but also the nephew of the owner. The election was hotly contested and he was defeated by a popular local doctor over whom the miners felt they could exert greater influence. Disillusioned, Coleman accepted Moxham's offer to take over as General Manager at the Johnstown mill in early April 1894. When Moxham moved to Lorain in January 1895, Coleman and his family moved into the Moxham residence across from the Von Lunen Grove.

The strategy of moving into the production of basic steel and relocating his primary mill operations to Lorain was insightful but unfortunately timed. Despite Moxham's persistent expressions of optimism, steel prices and rail demand remained low through 1897. The Johnson Company's cash position was already weakened by its practice of accepting rail and track work orders guaranteed by railway bonds rather than cash, and demand was not as strong as Moxham had hoped. Even profits from the Johnstown switch works lagged behind projections. At the Lorain site, the rail mill and company offices were completed by April 1895, but the company lacked sufficient capital to begin construction of the planned coke ovens and blast furnaces.

With risk capital in short supply and the du Pont holdings now fragmented among Fred du Pont's heirs, the Johnson Company had to choose between two equally distressing alternatives. One method of generating short-term capital quickly would have been to sell off its holdings of railway bonds at face value or at discount if necessary. But liquidating the railway bonds before they appreciated in value would have meant that Moxham would have to forego profits on the rail and trackwork orders for the past eighteen months. Many smaller companies caught in the credit contraction after the Panic of 1893 pursued the only other alternative - to borrow on the short-term market. The Johnson Company opted to borrow, hoping to cover the notes as they came due with the proceeds from successful sales of the additional stock issue, continued profits from the Johnstown switch works operations, and renewal of bonds held by members of the du Pont family, notably Pierre.

Unfortunately, none of these three sources performed to expectations and the redemption of maturing bonds became a constant struggle. Not surprisingly, purchase of the company's additional stock issue slowed to a trickle in the tightly contracted credit market. Many potential investors were put off by the fact that in 1894 the Johnson Company began to pay its very attractive 12% dividends in additional stock and stock options rather than in cash. For several of the du Ponts holding Johnson securities for income purposes and accustomed to high cash returns, this was a rude shock. Profits from the switch works in Johnstown continued to come in but at a much slower pace, at one point as much as 75% below Moxham's admittedly high projections.

The company was able to sustain its marginal position through 1895 by injections of cash from personal notes issued by New York and Wilmington banks to Richard T. Wilson, Jr. (the New York financier who had become the Johnson Company's treasurer after the death of Fred du Pont) and Pierre du Pont, who used their Johnson Company stock holdings as collateral. In February 1896, Moxham decided to go public in search of capital and applied to the New York Stock Exchange to list $1,245,000 in 6% 20-year gold bonds. Background screening by the R.G. Dun Company (the predecessor of Dun & Bradstreet) however produced a negative report on the company's liquidity position, questioning its ability to take care of maturing bond and note obligations. And while the Johnson Company was ultimately able to list its bonds on the Exchange in the fall of the year, the Dun report cast severe doubt on the collateral value of Johnson securities. Bank executives in New York and Wilmington balked at renewing the Wilson and du Pont notes, only agreeing to renew them after personal assurances from the two financiers.

Because of the investment strength of electrical manufacturers during this period and the high profit margin that appeared to exist in the Steel Motor Works, Moxham believed that more cash could be generated at the Johnstown mill if greater efficiencies could be achieved. To do this, Coleman du Pont brought in Frederick W. Taylor as a consulting engineer to reorganize and expand plant operations. Particularly, it was hoped Taylor could introduce systematic accounting and inventory methods in the motor factory, the switch works, and the foundries, all of which tended to operate as independent units. In the eight months Taylor worked for the Johnson Company, he was able to initiate programs that transformed the Motor Works into the most profitable of the company's operations. But as 1896 wore on and the company's need for cash became increasingly critical, Taylor's programs were cut back and he left the company in November without significantly changing any of the plant's tradition-bound mill floor practices.

The Lorain gamble would have been an astute move under ordinary circumstances. Further integration of operations to stabilize market share and assure access to production resources (such as ore and coke) turned out to be the appropriate defensive strategy for those steelmakers with the capital to pursue it. Unfortunately, Moxham lacked both sufficient capital and the mill capacity against which to borrow short-term when he attempted it in 1894. As history would demonstrate, the truly successful integrations in the steel industry would be accomplished several years later, and then only by those larger basic steelmakers who already had an established market share and were attempting to integrate production of finished steel into their manufacturing and market operations. Small steel fabricators like the Johnson Company simply did not have the capital or mill capacity to move into basic steelmaking.

By mid-1897, the financial condition of the Johnson Company was becoming desperate. Moxham was over-extended and unable to increase his market share or pursue production diversification as originally planned because the blast furnaces or coke ovens at the Lorain mill could not be completed. The anticipated advantages of locating the mill on the Great Lakes, with greater and cheaper access to the ore fields in Michigan and Minnesota, were never realized. In the first three years, the high-priced Lorain gamble produced nothing more than a sophisticated rail mill with the potential of becoming an integrated steel plant.

In a last-ditch effort to generate more capital, Moxham decided to reorganize the company altogether. In April 1898, he formed the Lorain Steel Company capitalized at $14 million and issued new 5% gold bonds. Lorain Steel then purchased all of the Johnson Company's assets in both Lorain and Johnstown, with those properties to retain the Johnson name until December 31, 1898. By that time, Moxham hoped that the increased capital from the refinancing would allow completion of the Lorain mill. At the end of April, he officially retired from the Presidency and Board of Directors of the Johnson Company and assumed the Presidency of Lorain Steel. By June, virtually all of the Johnson Company stockholders agreed to the plan except Pierre du Pont who still harbored reservations. The reorganization stalled.

It was sometime in the early summer of 1898 that Tom Johnson was approached by J.P. Morgan, the New York financier, about the prospect of including the Johnson Company in a proposed merger that would result in the formation of the Federal Steel Company. The Federal Steel merger was originally designed to create a holding company that would allow Illinois Steel to acquire controlling interest in the Minnesota Iron Company and thereby guaranteeing its access to the Great Lakes ore fields. Illinois Steel itself had been a merger of smaller Chicago steel companies ten years earlier. In early 1898 the steelmaker prevailed upon its attorney Elbert Gary to initiate a merger with the Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railroad. Gary in turn persuaded Illinois Steel that its real long-term interests would be better served by securing access to Great Lakes ore through the purchase of Minnesota Iron and expanding its manufacturing and marketing operations into finished steel products.

To accomplish the latter objective, Gary had suggested to Illinois Steel and its financial backer J.P. Morgan the possible acquisition of the Johnson Company, the prominent track work fabricator with established national and international markets. Johnson's assets, a sophisticated switch works in Johnstown and state-of-the-art rail mill in Lorain, were undervalued because of the company's over-extended debt structure and weak cash position. If Illinois could finance the development of basic steelmaking at the Lorain site, it could expand its overall steelmaking capacity and at the same time insure entry into the international market for finished steel products. It was a convincing argument and an irresistible opportunity.

For the Johnson Company, the Federal Steel merger was a godsend. In November 1898, the sale was completed and enthusiastically accepted by the Johnson Company stockholders. Considering the deteriorated cash position of the company, its stockholders received decent compensation from the sale of their assets to Federal. Granted that Johnson stockholders received only $28 per share market value in 1898 for stock that had a par value of $100 just six years before. But until 1894, that same stock was paying almost double the standard bond rates in cash dividends, and after 1894 continued to pay dividends in additional stock. Overall, all of the stockholders, including Johnson, Moxham and Pierre du Pont, realized a significant return from the sale.

In a calculated move, Tom Johnson decided to retain control of both the Lorain Street Railway and the Sheffield Land Company and they were not included in the merger. They would in fact bear the Johnson Company name for another twenty years. Johnson's reasons were good ones. If Federal Steel was successfully financed and did invest in the completion of the primary mill at Lorain, one could expect employment levels at Lorain Steel to rise. A growing steel mill would increase the demand for residential, commercial and light industrial property surrounding the mill site and improve the depressed value of Johnson's Sheffield holdings. Population growth in the area would increase local railway revenues, routes might expand and more growth result. If all went well, in a few years Johnson might yet realize a healthy return on his land investments in Lorain.

The Johnson Company proceeded to transfer its two mill properties (Lorain and Johnstown), the Steel Motor Works, the Johnstown and Stony Creek Railroad, and the Ingleside Coal Company to Moxham's Lorain Steel Company. On December 31, 1898, the two Johnson facilities officially became the property of the Lorain Steel Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of the holding company known as Federal Steel. The Johnson Company name, associated prominently with steel track work for close to fifteen years was officially changed to Lorain Steel on May 22, 1899. Even before the sale of assets was completed, Gary began construction of the needed blast furnaces and coke ovens at Lorain. Within a year, Federal Steel had tightened and integrated its operations and showed a substantial profit. For the Johnson Company, its short reign as the premier street railway track work fabricator in the United States had come to an end, almost sixteen years to the day after the company was chartered in Louisville.