(CANON) AGGREGATE

Genre

This chapter examines the AC in terms of genre. As you may know, genre is a loaded, subjective, ill-defined term which seeks to act as a grouping system for texts within it. The function of these groups may be stated to act as a guide for the reader, setting an expectation as to the type of content within the text. As Daniel Chandler notes in An Introduction to Genre Theory: "Genres can be seen as a [system of generic expectations, or a code]...which amounts to a shorthand serving to increase the 'efficieny' of communication" (7). Chandler utilizes Fowler's definition of genre code, and explicates on it as a means of "shorthand" to understanding textual implications. He further notes that "Defining genres may not seem particularly problematic but it should already be apparent that it is a theoretical minefield" (2). He goes on to quote over a dozen various scholars' points of view on genre itself, ranging from how genre can be used to stifle creativity (7) to a more nuanced, modern view espoused by Gledhill, Fowler, and Rosewater - namely, that "Restrictions breed creativity" (Rosewater GDC), (Chandler 7). He describes how "Conventional definitions of genres...are [constituted] of content (such as themes or settings) and/or forms (including structure and style)" (2). Bordwell, another genre scholar specializing in film text, mentions that "...no set of necessary and sufficient conditions can mark off genres...that all experts or ordinary film-goers would find acceptable" (147), and Chandler, amidst a wide-ranging discussion of purpose (another ill-defined term), notes that "How we define a genre depends on our purposes" (3).

This chapter examines the AC in terms of genre. As you may know, genre is a loaded, subjective, ill-defined term which seeks to act as a grouping system for texts within it. The function of these groups may be stated to act as a guide for the reader, setting an expectation as to the type of content within the text. As Daniel Chandler notes in An Introduction to Genre Theory: "Genres can be seen as a [system of generic expectations, or a code]...which amounts to a shorthand serving to increase the 'efficieny' of communication" (7). Chandler utilizes Fowler's definition of genre code, and explicates on it as a means of "shorthand" to understanding textual implications. He further notes that "Defining genres may not seem particularly problematic but it should already be apparent that it is a theoretical minefield" (2). He goes on to quote over a dozen various scholars' points of view on genre itself, ranging from how genre can be used to stifle creativity (7) to a more nuanced, modern view espoused by Gledhill, Fowler, and Rosewater - namely, that "Restrictions breed creativity" (Rosewater GDC), (Chandler 7). He describes how "Conventional definitions of genres...are [constituted] of content (such as themes or settings) and/or forms (including structure and style)" (2). Bordwell, another genre scholar specializing in film text, mentions that "...no set of necessary and sufficient conditions can mark off genres...that all experts or ordinary film-goers would find acceptable" (147), and Chandler, amidst a wide-ranging discussion of purpose (another ill-defined term), notes that "How we define a genre depends on our purposes" (3).

Suffice to note two critical caveats at this juncture: firstly, this examination is not designed to a be thorough examination of genre theory and the philosophical and theoretical complications therein (a goal for a different project); and, secondly, this examination of genre within the AC utilizes my own taxonomy of genre which I have crafted in an attempt to better organize and structure these texts. I fully anticipate most individuals will disagree with some, all, or even a minor part of my classification system - the nebulous nature of genre theory grants anyone that perogative. As Chandler reminds us, "...the analogy with biological classification into genus and species misleadingly suggests a 'scientific' process" (1), and, much like the canon in general, empiricism is far from the minds of genre organizers. There is perhaps a scientific genre theory to be had via the application of distant reading in examination of text for various themes, but as these themes tend to emerge over wide tracts of text, and many are intuited by the reader, such an application of empirical genre theory remains, for the moment, beyond our grasp. What I have presented here is an attempt to be as direct and clear as possible without lending too much preference to particular genres or their respective features, no matter at what level they may fall.

A Question of Taste

The genre taxonomy I devised and employ is listed in detail below. Note that this is not a full explanation of this theory (you may find that within another of my DH projects), but I have attempted to summarize the system to the best of my ability. The model, as it were, is based off of biological taxonomy models, with various degrees and aspects renamed such that multiple texts may retain multiple "umbrella" terminologies. At the highest level, Status, we divide between "Fiction," "Nonfiction," "Special," (which includes documents which are intended to be founding government documents, directions, or the like), and "Multiple," which includes texts that mix both fiction and nonfiction together (The King James Bible, for example). This level is examined in detail in Chapter Three.

The next level, Format, deals with the structure which dominates the text - "Prose," "Verse," "Mixed," (both poetry and prose), and "Unique" (texts which are neither, like Joyce's Finnegan's Wake). Our third rung down the taxonomic ladder deals with Format: "Novel," "Novella," "Epic," "Sonnet," "Essay," and so on. This category is dealt with extensively in Chapter Four. Immediately below the rung of Format lies the taxonomic classification of Audience, wherein a text is classified as Children's Literature, Young Adult Literature, or Adult literature. Further delineations might be made within this category, but for the moment we will merely mention it.

This chapter is primarily concerned with genre classifications that are found below the level of Audience; that is, Aim, Theme, Subtheme, Aesthetic, and Setting. This chapter will not attempt to explicate justifications for particular genre tags (again, it is not the aim of this project to engage in genre theory discussion), but rather to document the presence of each particular genre within the AC. When possible, I will detail the full breadth of genre tags within each taxonomic level, such that the reader may hopefully gain a perspective of what is generally examined. The chart below details the basic taxonomic structure I employ, alongside the "classic" biological taxonomy which served as inspiration for my category selections.

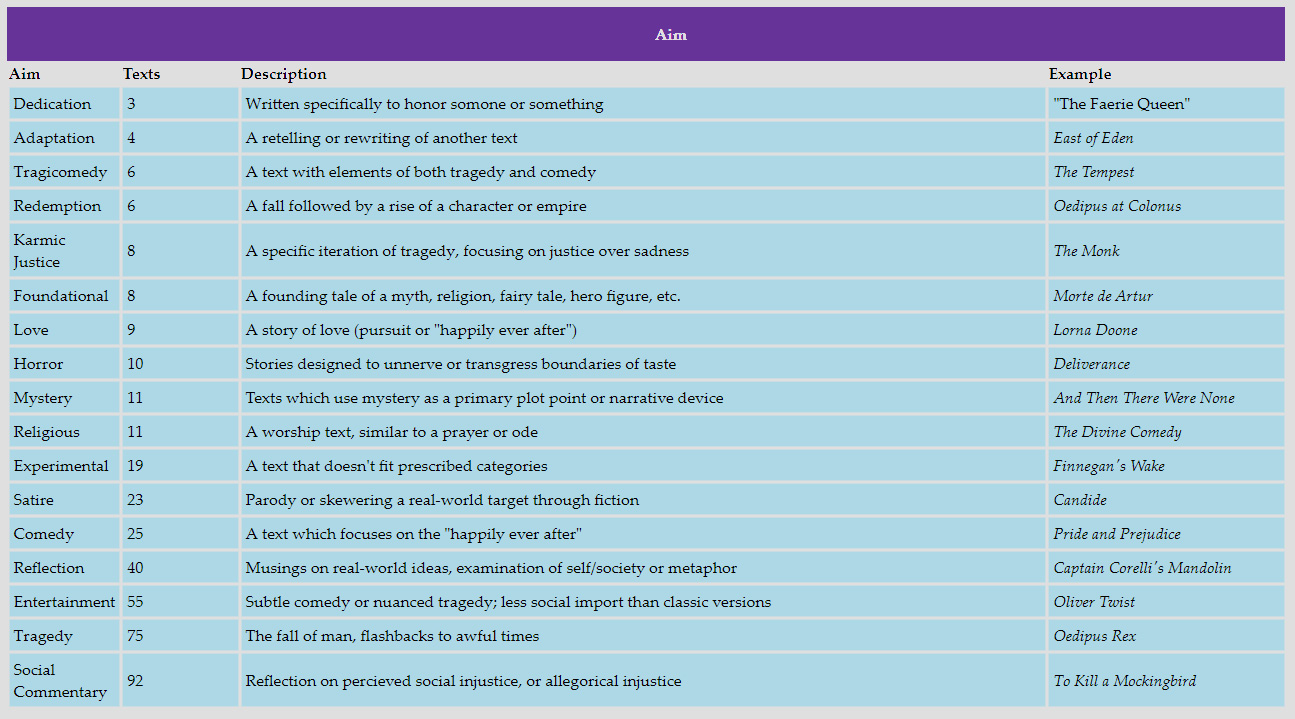

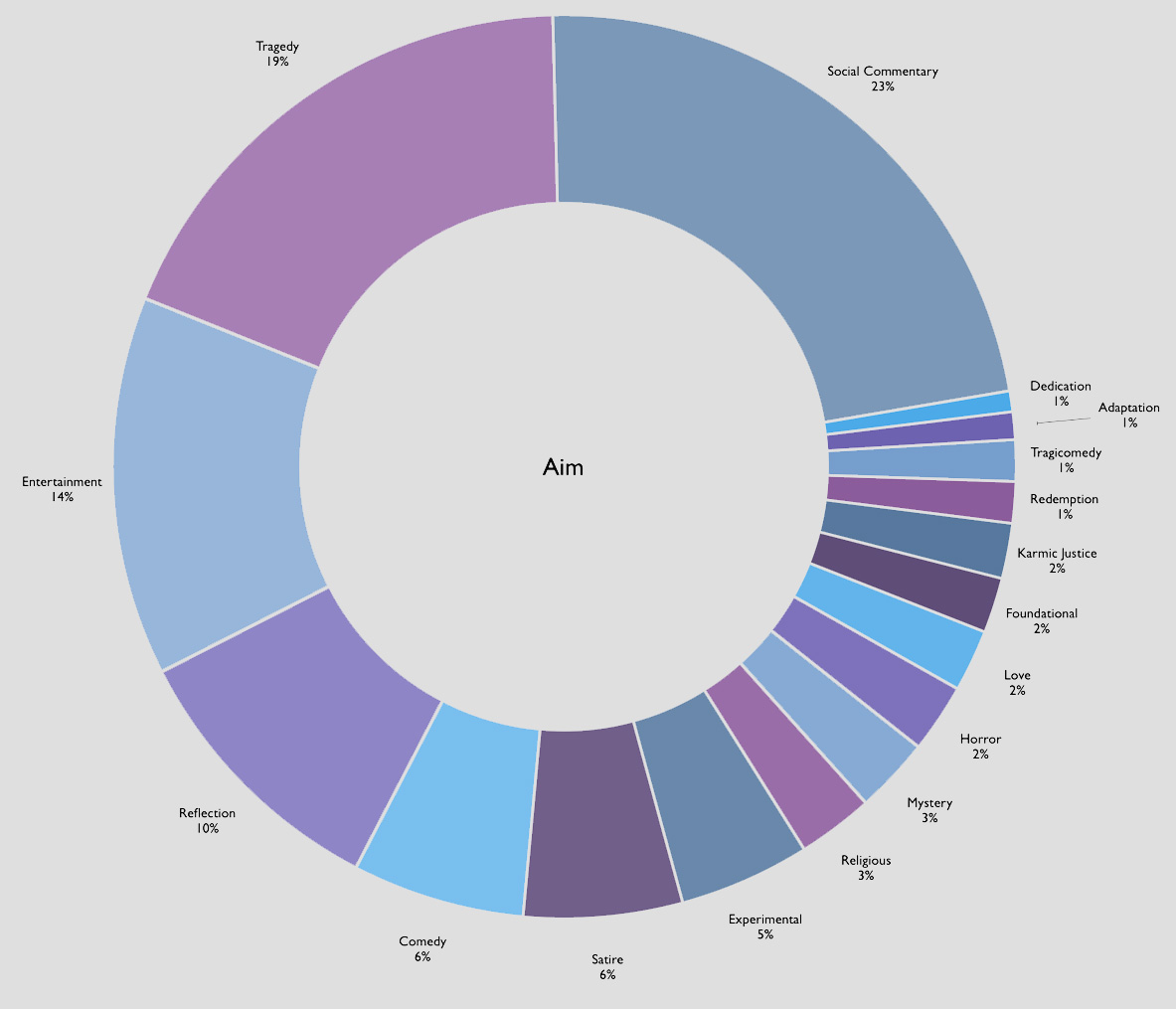

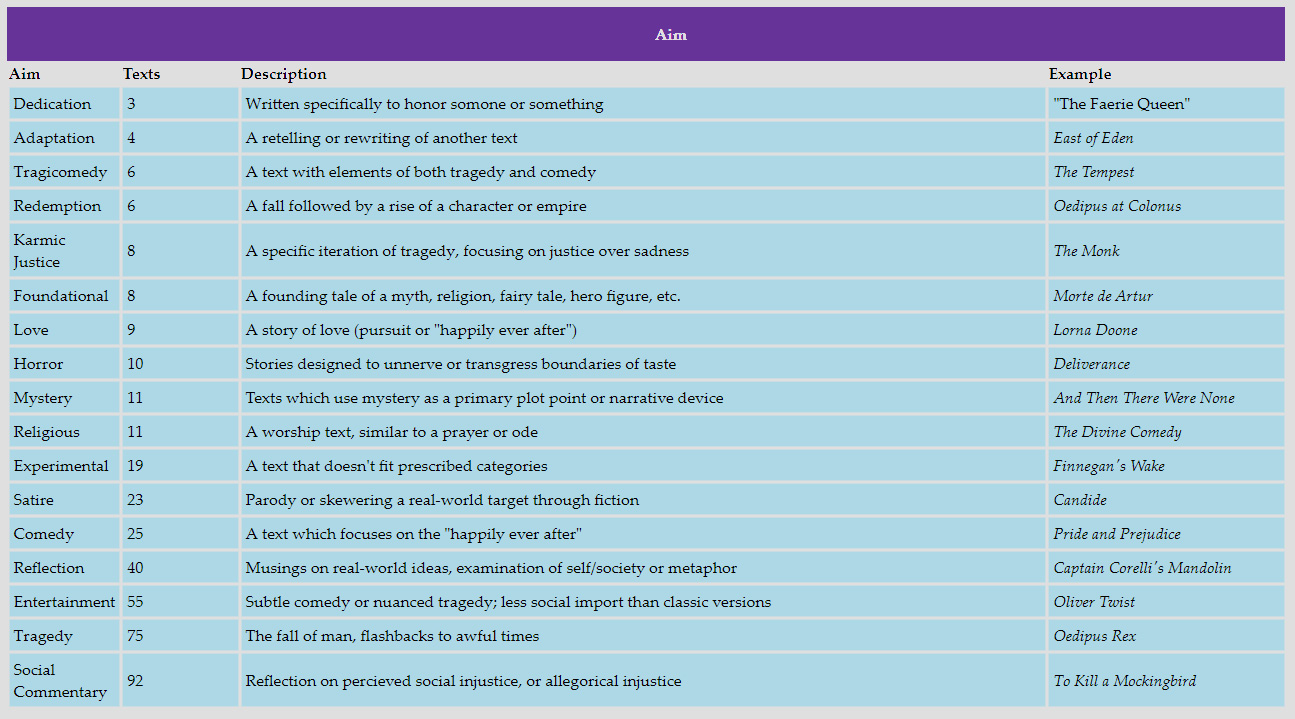

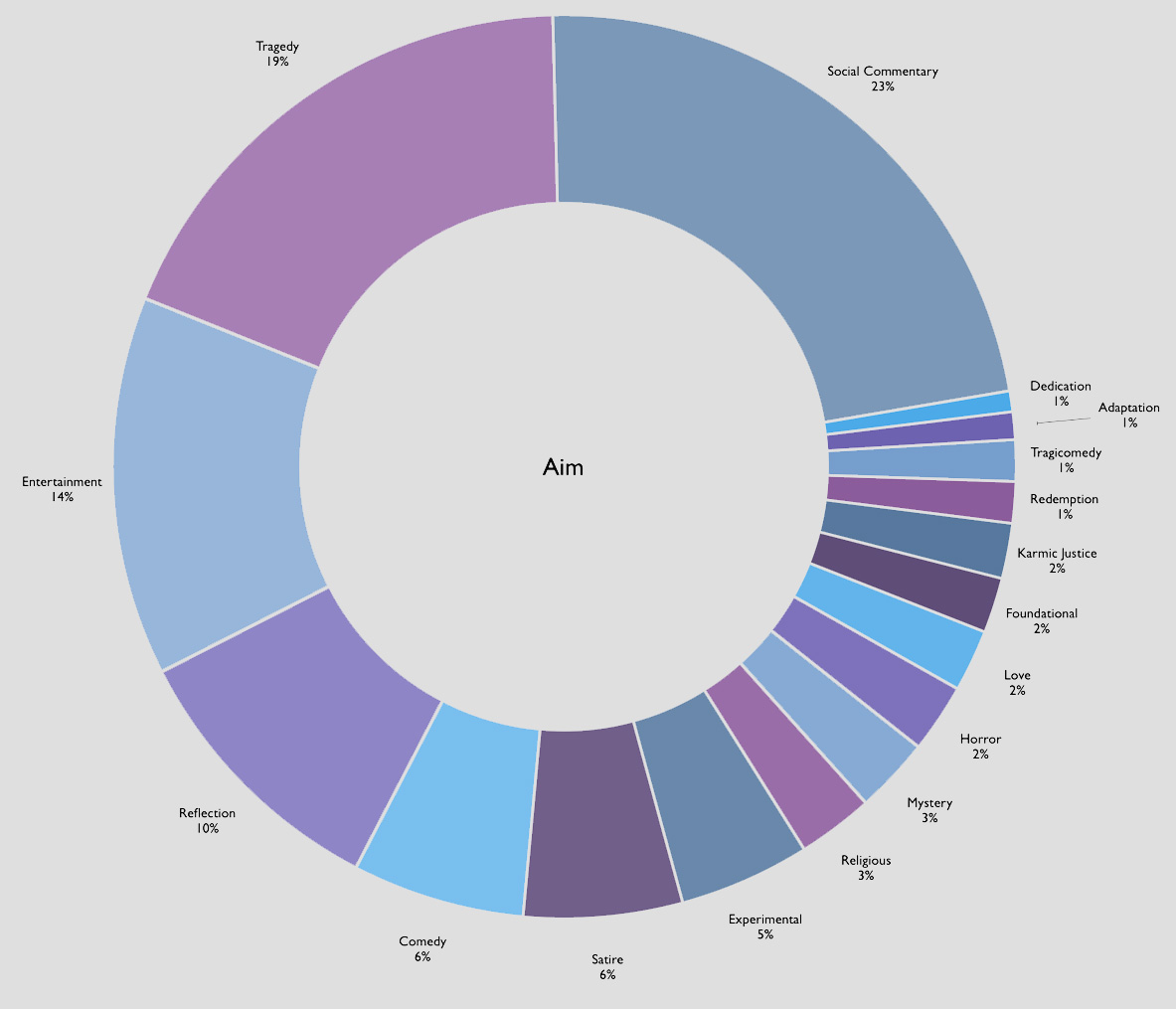

Aim: This tier examines the "purpose" behind the literature. Perhaps the most subjective of all the tags, as "purpose" itself is a loaded, ill-defined term, this tag deigns to define exactly what purpose the author had in writing the text. As purpose shifts with various audience interpretations and across various historical time periods - and some purposes may only be identified in hindsight - this tag is readily expected to stir up much disagreement. It includes terms like "Social Commentary" (1984, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Deerslayer); "Entertainment" (Pride and Prejudice, The Three Musketeers, Richard II); "Satire" (Gulliver's Travels, The Dunciad, Candide); "Religious" (The Divine Comedy, Young Goodman Brown); and, the most-utilized tags within the canon, "Tragedy" and "Comedy." Other tags found within Aim include "Reflection," "Redemption," "Mystery," "Karmic Justice," "Horror," "Foundational," "Experimental," "Dedication," "Adaptation," and "Tragicomedy." A detailed explanation of each tag may be found later in the chapter with our data.

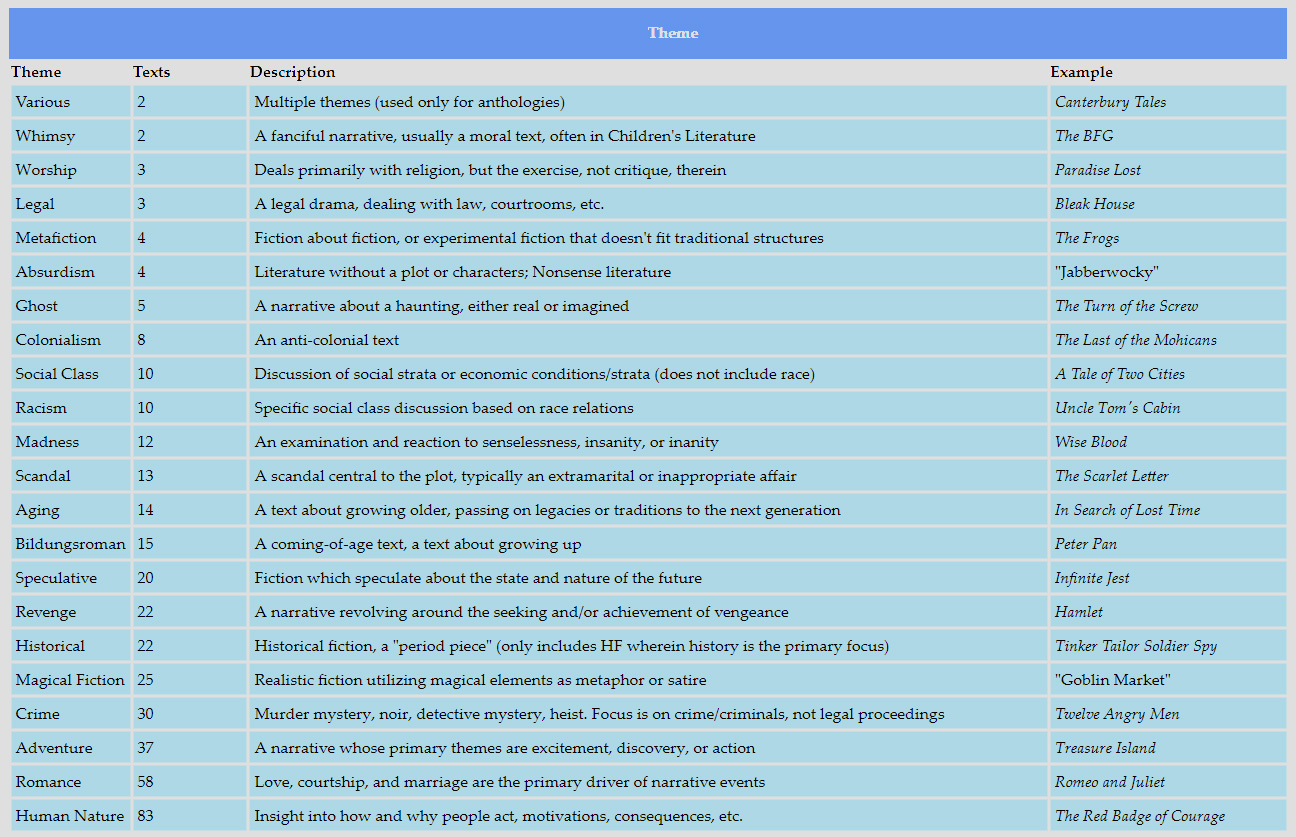

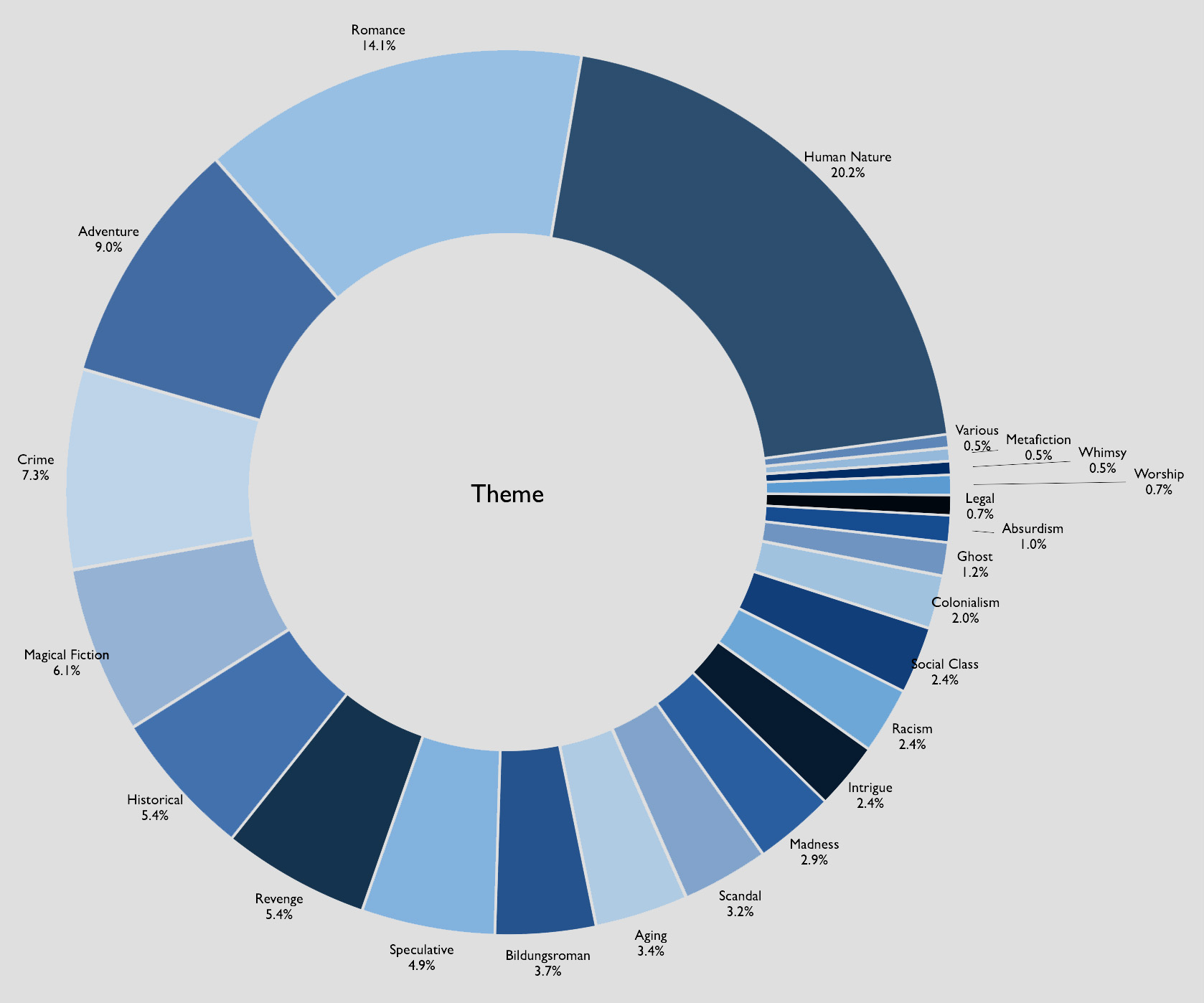

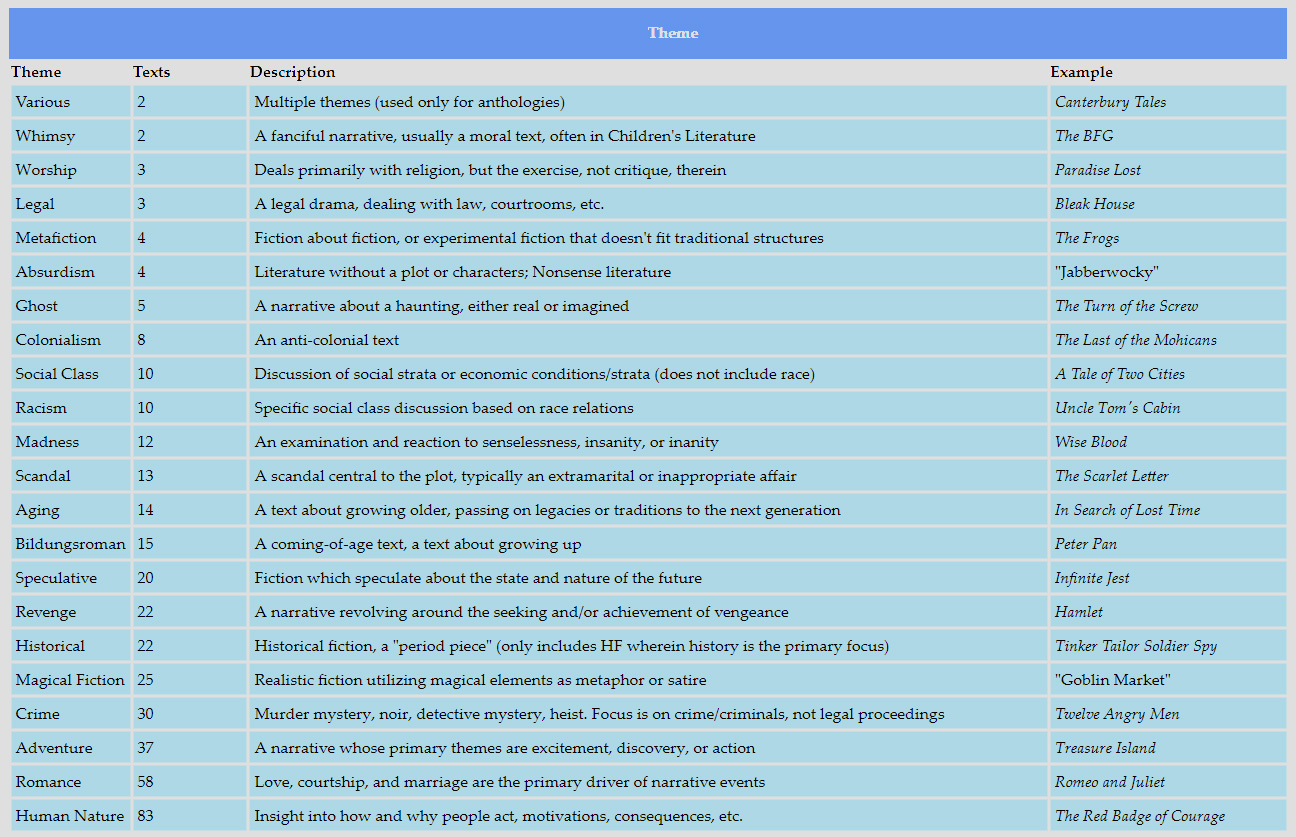

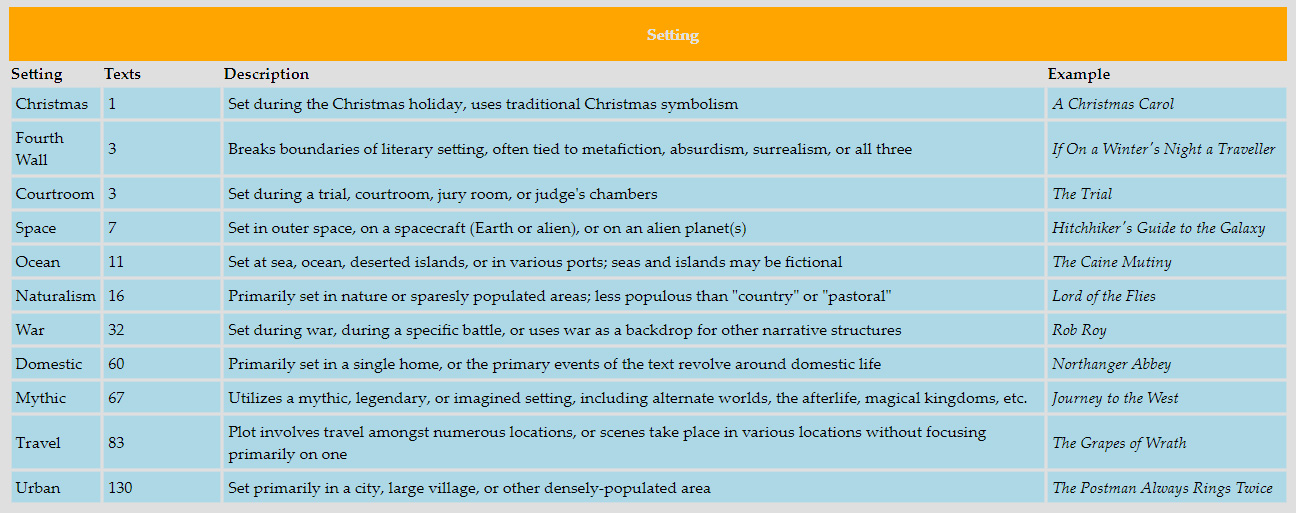

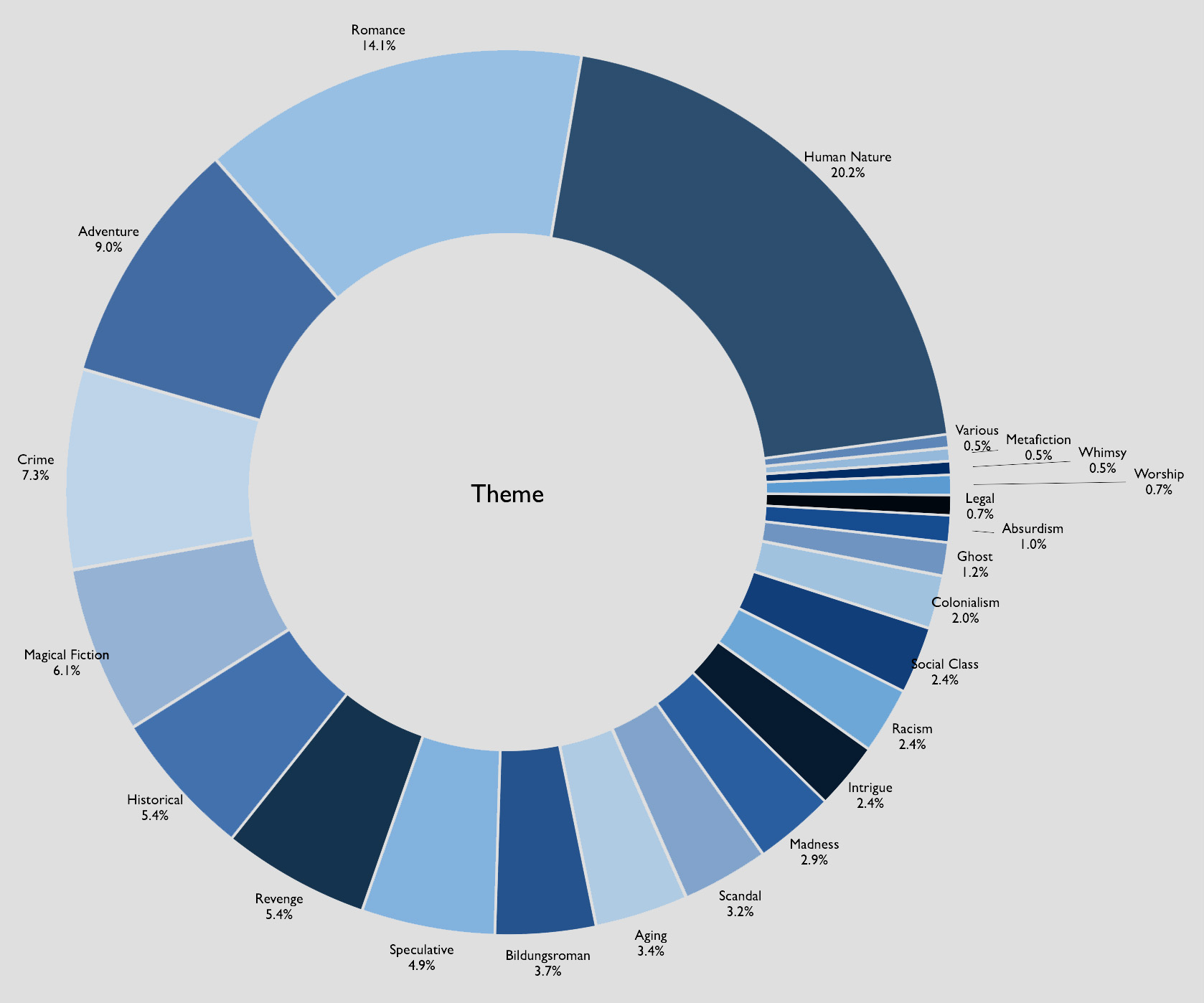

Theme: Our next level of genre taxonomy, theme, refers to the method in which the material is treated, as well as the subject matter in question. This means that the tag examines texts like "Romance" (Jane Eyre, Pride and Prejudice), "Madness" (Don Quixote, The Bell Jar, The Fall of the House of Usher), "Magical Fiction" (Midnight's Children, Manfred, Rip Van Winkle), and "Revenge" (Titus Andronicus, Prometheus Bound, Ben-Hur). This level, theme, is perhaps what most individuals consider when they think of "literary genre," as a thematic interpretation is one of the key drivers of taste when selecting a text. Note that it is below Audience, taxonomically speaking, as you will likely not find many "Children's Horror Novels," for example, but the possibility nonetheless exists. As with all genre tags, a detailed breakdown of all tag options may be found below.

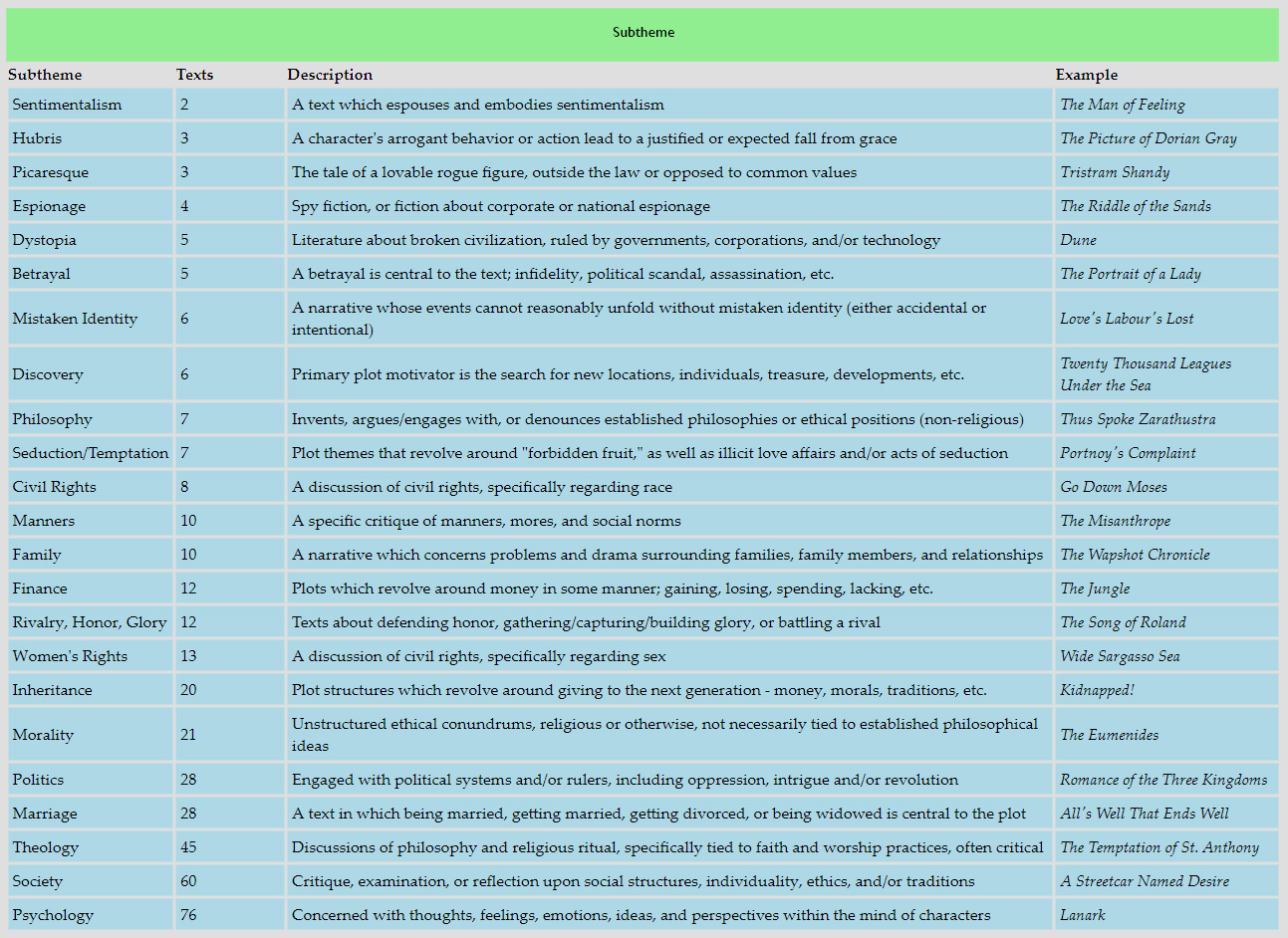

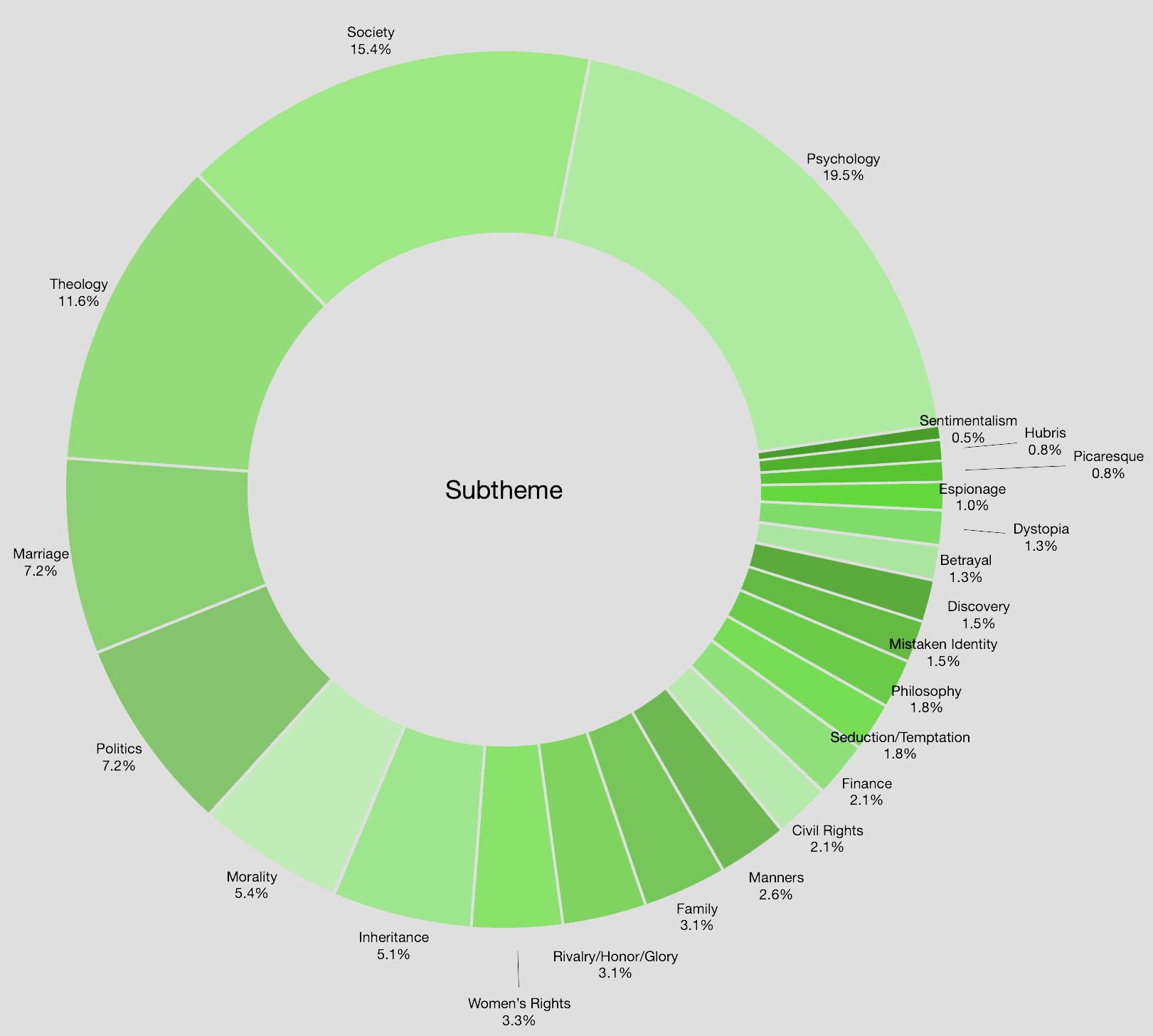

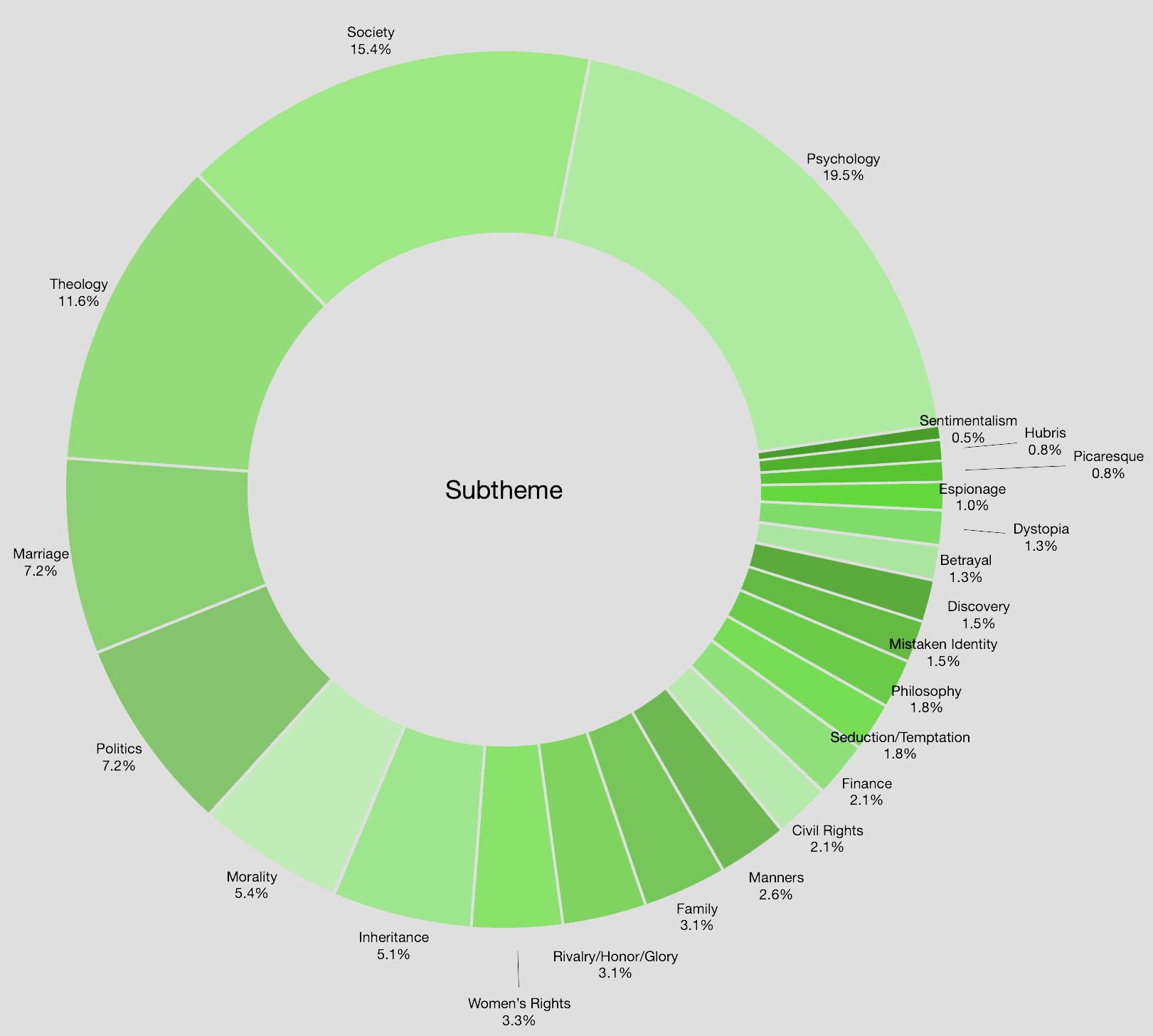

Subtheme: Our next level refers to the individual specific content treated within the theme of the text. Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado," for example, has a theme of "Revenge" (sought against Fortunato), but the subtheme is "Psychology," as the text emobodies the psychological horror of being buried alive. There are 24 subthemes (as well as 24 themes), each dealing with the manner in which the theme is presented. A text about scandal (theme), for example, may be presented with an emphasis on politics (subtheme) or marriage (subtheme). In this way, the scandal may be either political or dealing with infidelity. A full list of subthemes and their various descriptions may be found below.

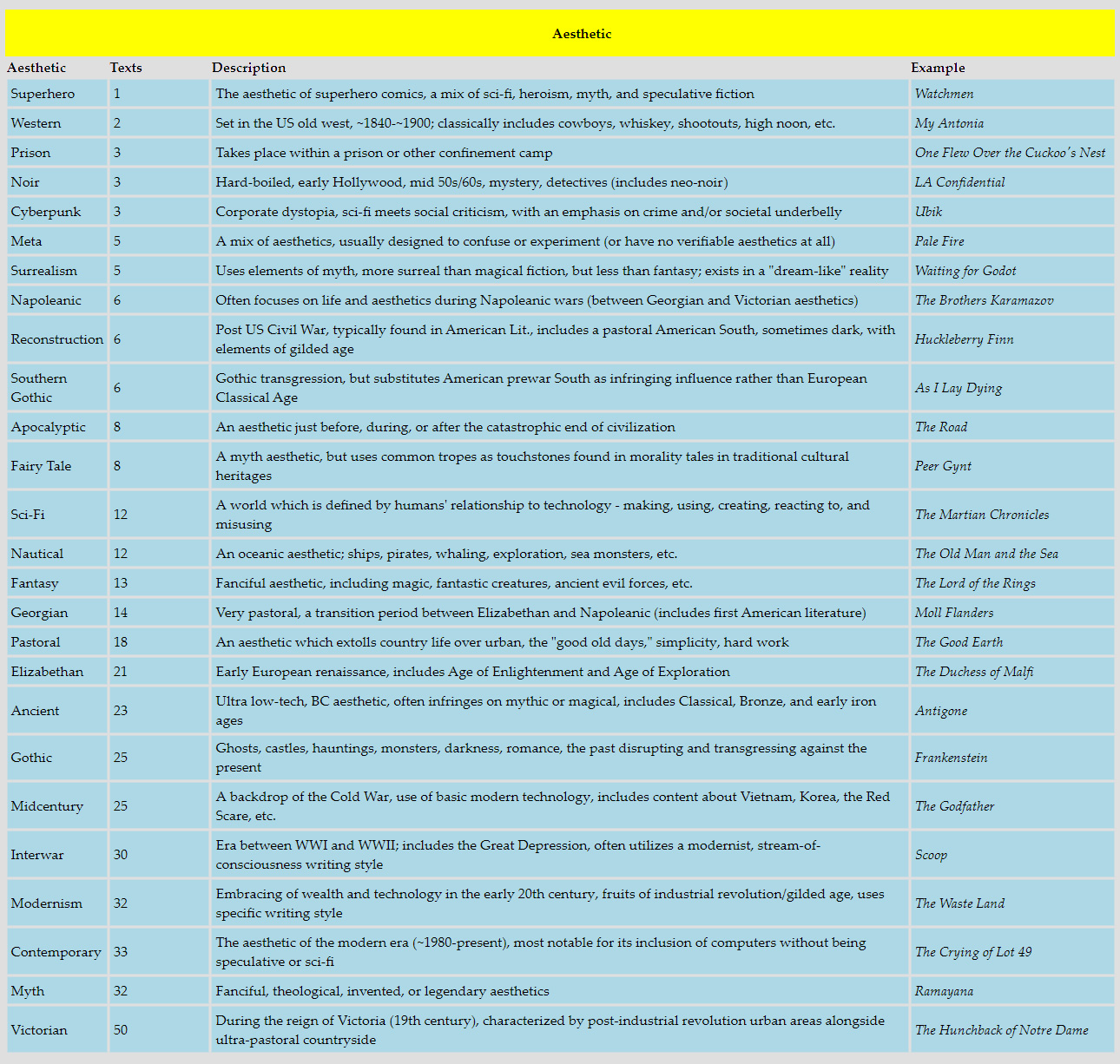

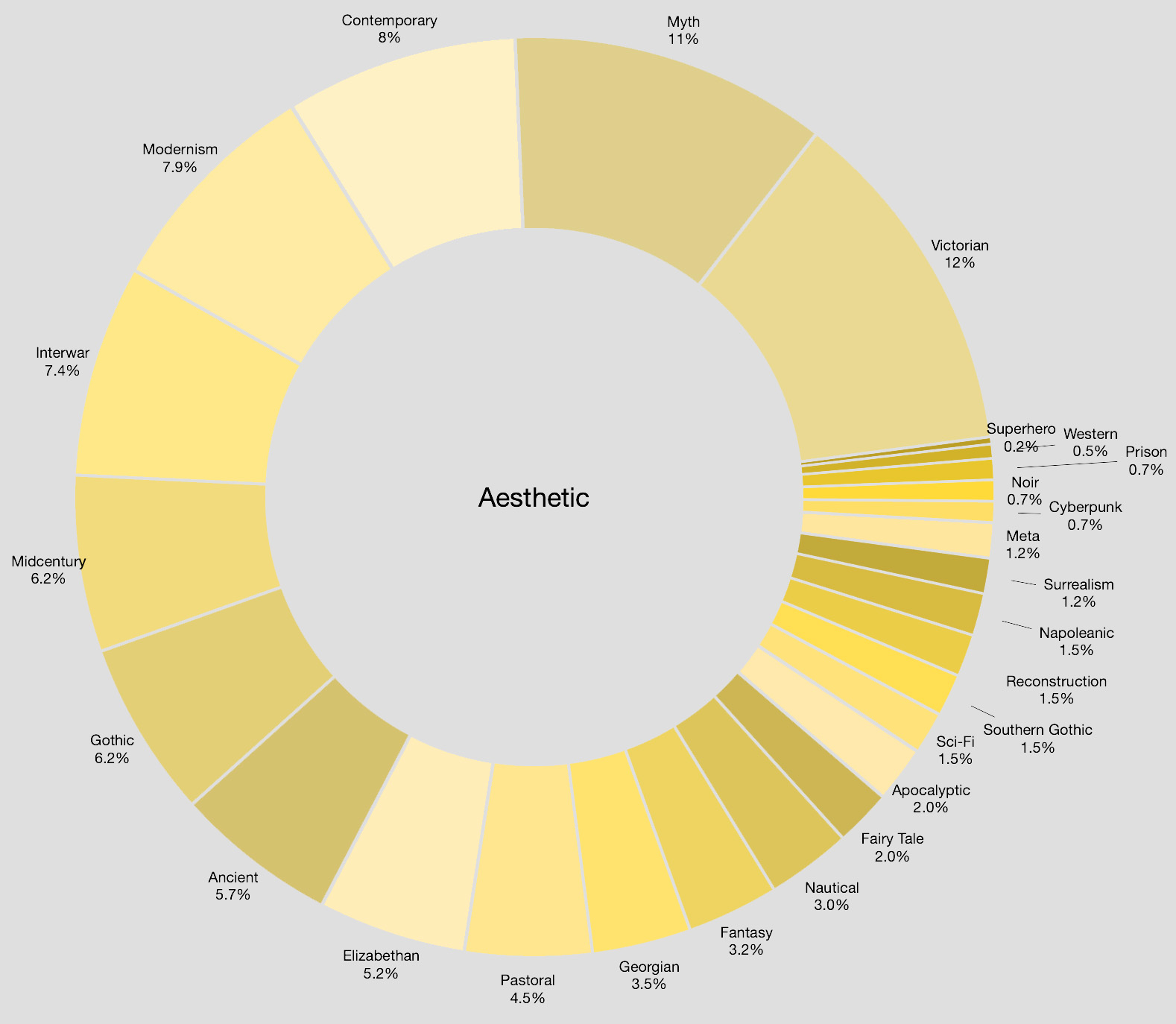

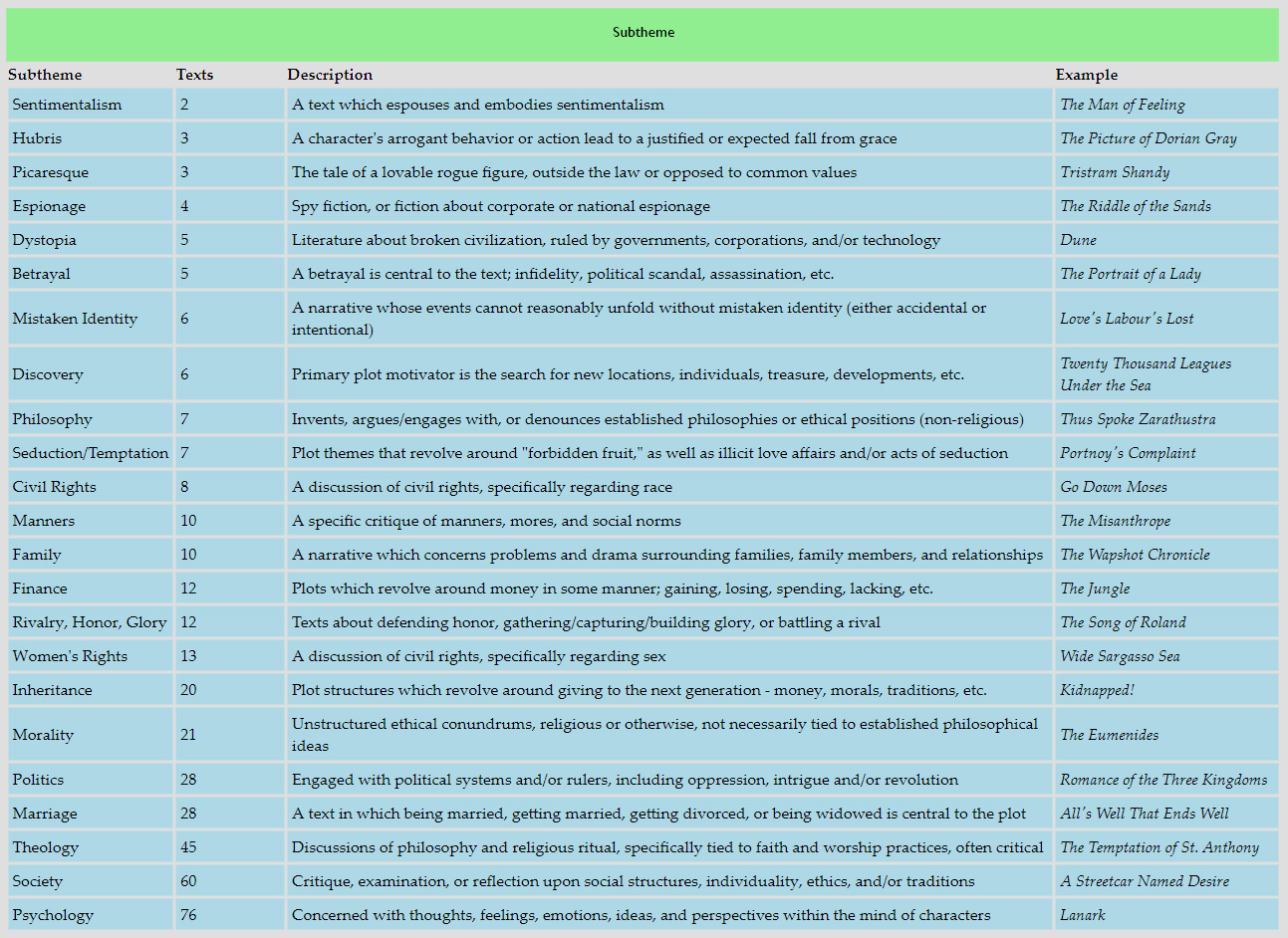

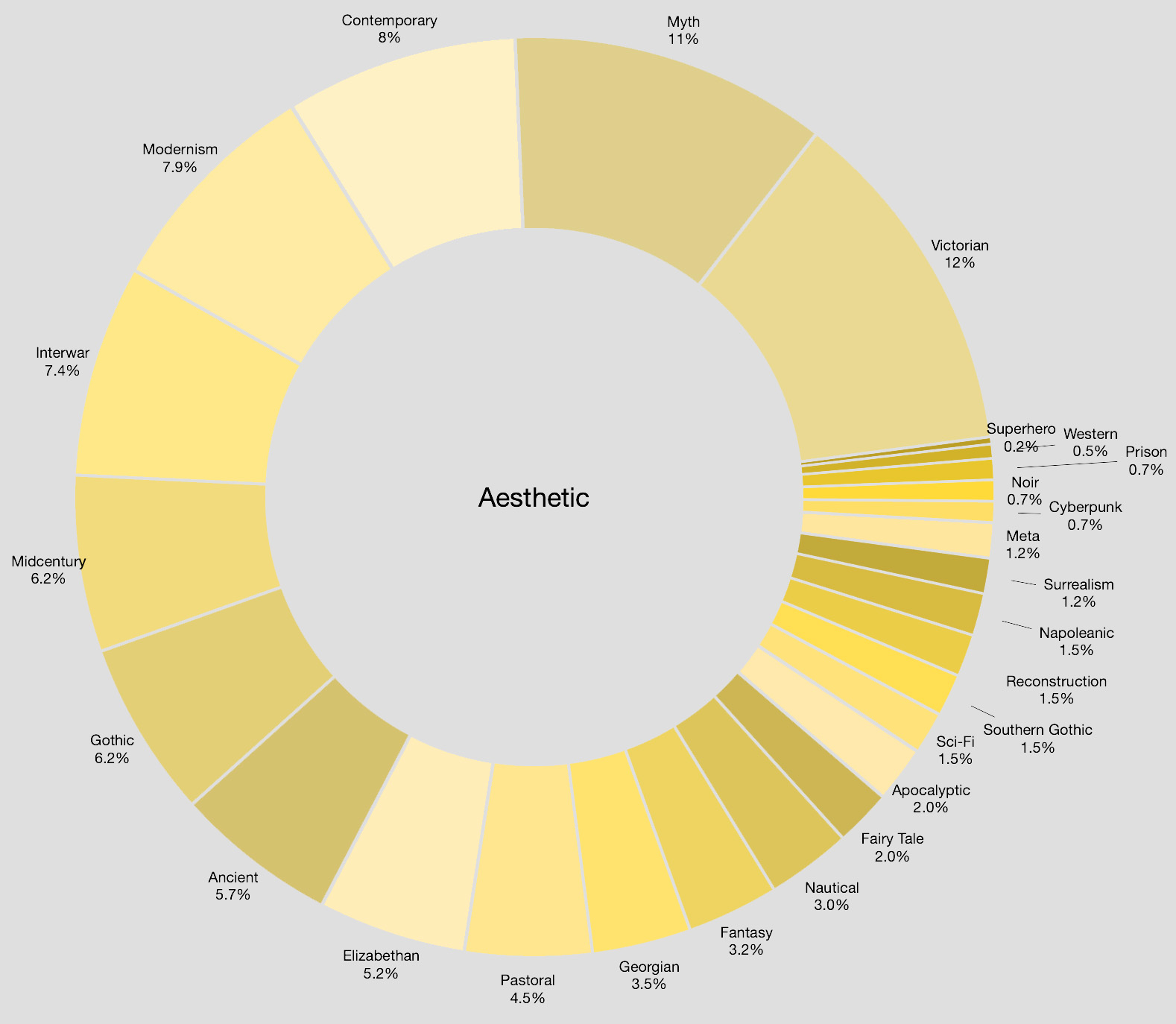

Aesthetic: The largest and most broad category, Aesthetic deals not necessarily with subtext within a work, or how it is presented, but rather the aesthetic employed to accomplish these goals. Alongside "theme," "aesthetic" might be the category most individuals describe when discussing textual genre in the abstract, as it often substitutes for film and television, as well. Examples of an aesthetic include "Sci-Fi," "Western," "Noir," "Gothic," "Victorian," and "Fantasy." As most authors tend not to write historical fiction, preferring fiction that resembles their home times and countries, often the aesthetic is closely pinned to a time period, like "Georgian," "Napoleanic," "Reconstruction," "Ancient," or "Midcentury." There are 26 aesthetics utilized in this list, and some texts could reasonably have multiple aesthetics (Death Comes for the Archbishop, for example, could be equal parts "Gothic" and "Western.") When encountering entries that have multiple options, I selected the one which more audiences would be more likely to identify the text as, while trying to reflect the other aesthetic through further genre tags. This is true of every level of the taxonomy.

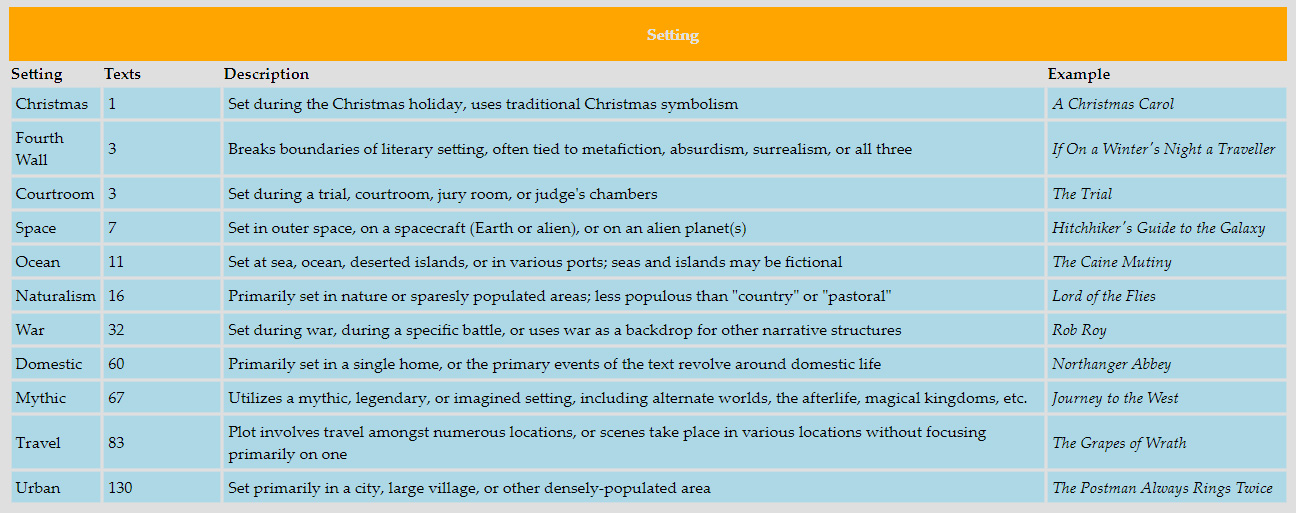

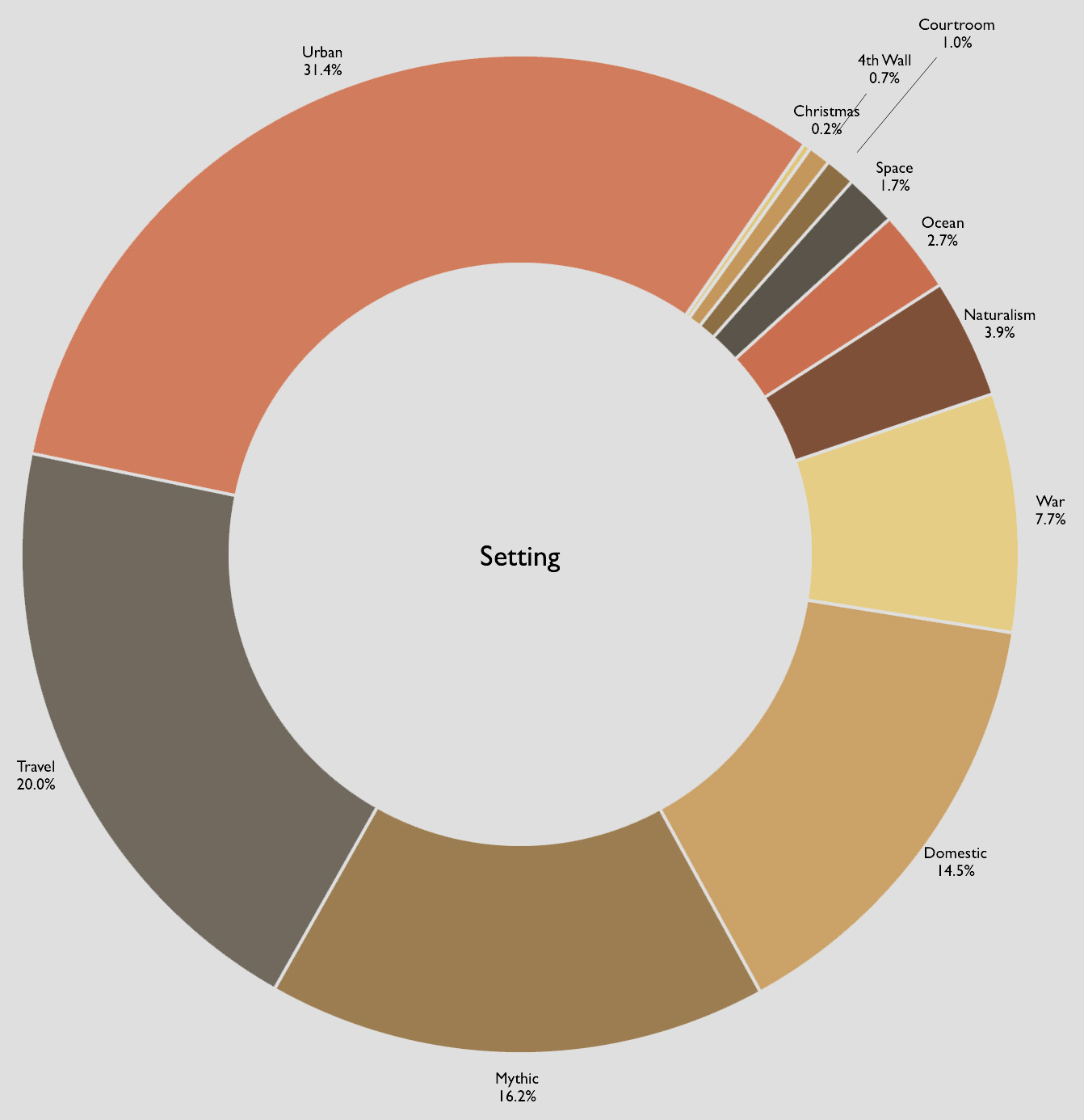

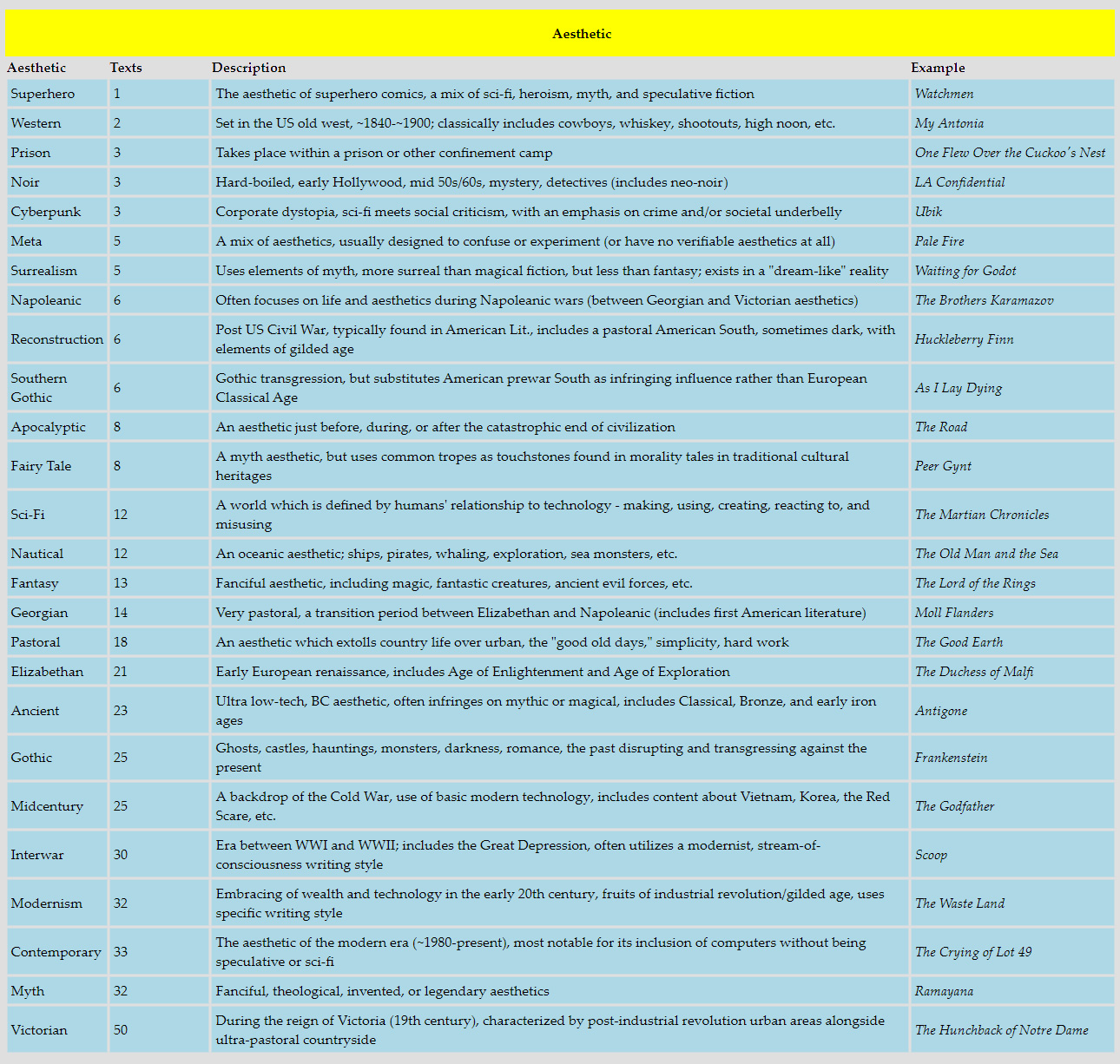

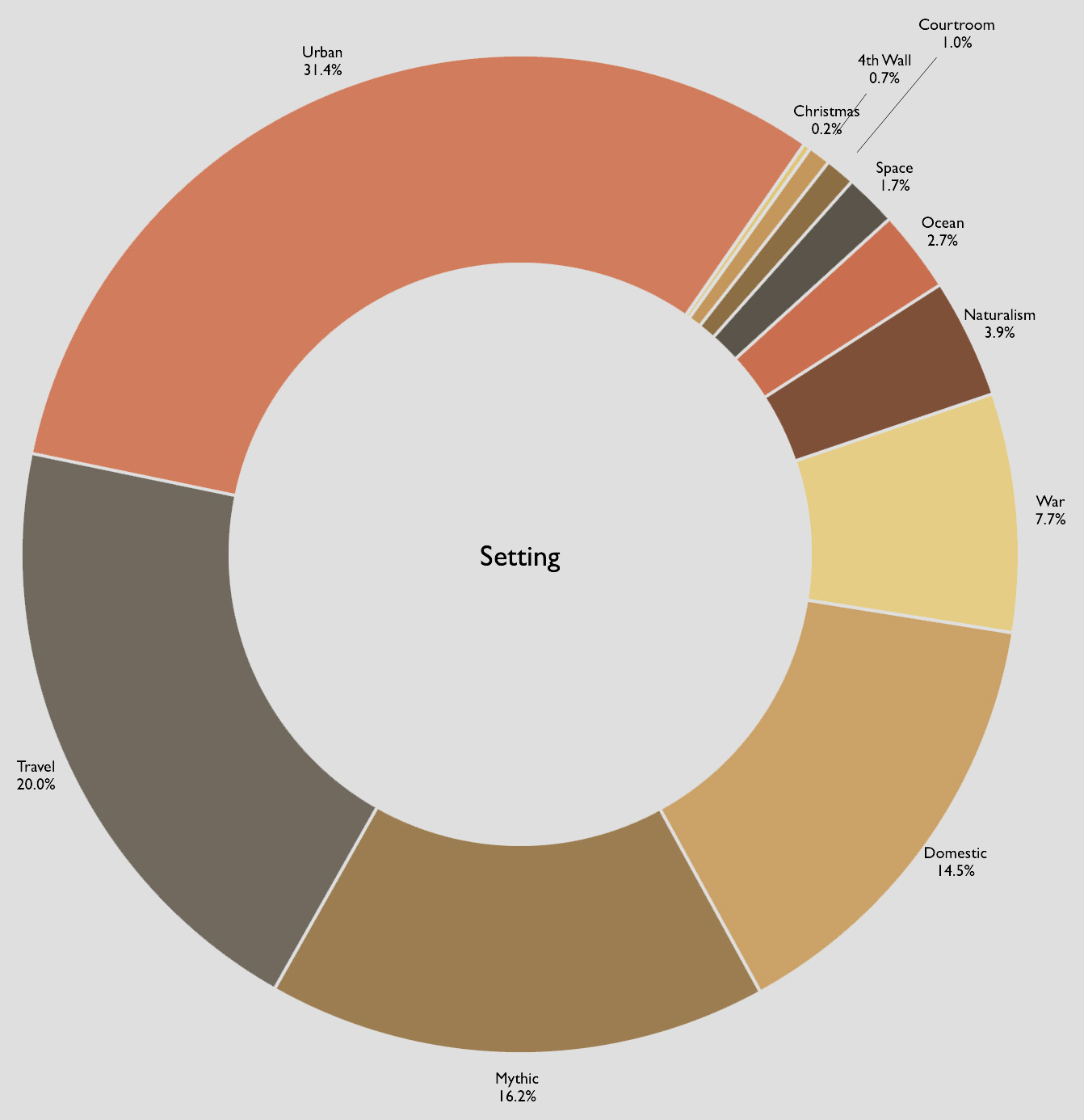

Setting: Our final tier on the taxonomic list is the most granular, though also the tier that has the fewest entries. "Setting" is designed to examine the area wherein the bulk of the text is set - "Domestic," for example, takes place primarily within the home of a character, or is centered around a home (Little Women, The Color Purple, The Turn of the Screw). "Urban" refers to texts that take place primarily within cities (Herzog, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Anna Karenina). Other categories include "Courtroom," "Space," "Ocean," "Mythic," and "Naturalism." A detailed explanation of each tag may be found below. Note that text marked with the "Travel" setting tag indicates text which is often set in a multitude of locations - either through various interconnected plots, or a character(s) whom move throughout the narrative (The Count of Monte Cristo, Orlando: A Biography, The Ambassadors, Cat's Cradle, The Good Soldier.)

An example of how our taxonomic system functions allows us to enter a text and determine where, exactly, it is located within our structure. Our number one overall text, for example, Pride and Prejudice, would rank as follows: Status: Fiction, Format: Prose, Mode: Novel, Audience: Adult, Aim: Comedy, Theme: Romance, Subtheme: Manners, Aesthetic: Pastoral, Setting: Domestic. The charts below show all available taxonomic tags at each level of the sorting algorithm from "Aim" to "Setting," alongside explanations and examples of texts which use them.

Breaking Things Down

As you'll likely notice from the assortment of charts above, dividing the AC into genres was no small task. Before we begin examining our results, we must first disclose the methodology used to build these lists. As explained in the chapter introduction, the taxonomy was used to divide texts into various genre classifications, with an attempt to focus on the primary driver within each text, either of plot or characterization, with special emphasis paid to texts with memorable scenes that may be seen as highly influential on genre. At its heart, however, genre classification is nothing more than opinion - not unlike inclusion on a canon list, ironically - and therefore it is possible, indeed likely, that minor division classification disagreements will arise. I expect this and welcome it.

Additionally, please note that not all of the texts on the AC are represented within this genre list. In order to qualify this data, the first step was to eliminate any text that did not fit genre criteria, chiefly, nonfiction. Nonfiction texts are not written in a "genre," but rather are written on a subject, and their various aims and directions would disrupt the data and result in dozens, if not hundreds, of single "one-off" genres. With nonfiction eliminated, the next step was to eliminate texts which had a drastic diaspora of genre, chiefly, anthologies. A few anthologies remain (for example, Canterbury Tales and Lyrical Ballads), but the bulk of anthological text, usually, but not always, poetry, was removed. Each various short story within the text could be said to be deserving of its own genre entry, and as these various texts did not otherwise appear on the AC, I thought it best to remove them from contention.

Finally, you will no doubt note that many texts fit into multiple genre tags. Beloved, for example, has the following tags on my taxonomy: Fiction, Prose, Novel, Adult, Social Commentary, Magical Fiction, Civil Rights, Contemporary, Domestic. An argument could easily be made to shift the Magical Fiction tag to the Ghost tag, the Racism tag, the Revenge tag, or even the Crime tag (all of which are in the Theme category). Further, the Subtheme is labeled as Civil Rights, but could easily be Society, Psychology, Family, or Inheritance. Finally, the text is also labeled Contemporary, owing to the modern setting, but maintains consistent flashbacks that could reasonably make it Georgian, Napoleanic, Reconstruction, Southern Gothic or Prison. This is just one of many subjective examples of the auditing that had to be done with this data, and, as previously stated, I expect that not all of my selections will necessarily be the same as yours. This being said, however, I do believe that this list is, in addition to being quite exhaustive, also extremely beneficial in demonstrating the types of subject matter and content that we appreciate within the tradition of literary studies.

What Do We Like?

The charts below illustrate the data from the above tables in a more readable format. Each chart is color-coded to align with a different taxonomic metric used to determine taste within text. Note that after removing the anthological and nonfiction texts, we were left with 407 (of 532 original) texts to categorize. All percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number. If it appears on the chart in any way, then it produced at least a single result within the data analysis. The charts above detail the specific definitions used to direct each category tag.

The most prominent Aim within our sample is, unsurprisingly, Social Commentary, with almost a full quarter of the entire AC's fiction dedicated to affecting some kind of social change, whether that be in regard to race, sex, social class, or other characteristic. The majority of these texts originate from the 20th century, which should also not be a surprise, though a good deal are also from the 19th century as well (or are set during the 18th or 19th centuries). The second most common aim was Tragedy, followed by Entertainment, Reflection, and Comedy. Surprisingly, Satire and Experimental were next, demonstrating our affection for the darkly humorous and the strange. These were followed by the smaller Aim groups; in order: Religious, Mystery, Horror, Love, Foundational, Karmic Justice, Redemption, Tragicomedy, Adaptation, and finally Dedication. The Theme category was a bit more complex, offering more options for texts to align, though a large number remained consistent, usually those within the Social Commentary Aim. The highest-scoring Theme was the broad category of Human Nature, followed by Romance, Adventure, Crime, Magical Fiction, Historical, and Revenge. Numerous smaller categories exist as well, ranging everywhere from Speculative Fiction to Colonialism to Metafiction. These Themes are further influenced by their respective Subthemes, which saw Psychology leading the way (with almost 1 in every 5 texts querying the human mind), followed closely by Society, Theology, Marriage, Politics, Morality, and, in a surprising display, Inheritance. Some of the more recognizable subthemes, like Dystopia, Civil Rights, Sentimentalism, and the Picaresque finished further down the list. The most popular Aesthetic was a virtual tie between Victorian and Myth, with Contemporary, Modernism, Interwar, Midcentury, Gothic, Ancient, and Elizabethan comprising the next tier. Note that we might say Contemporary has always been the most popular aesthetic, as the relative publication dates of many of these texts make their settings contemporary for their own time. In other words, most authors - the vast majority, in fact - seem to write non-historical texts. The most popular Setting, by a (very) wide majority was Urban, followed by Travel (usually between various urban settings), Mythic, Domestic, and, a tier below, War.

Aim, Theme, and Subtheme

As previously discussed, the examination of genre is a difficult one, owing both to subjectivity and various influences. Let us also not forget that genre may change over time; as Barthes notes in the famous essay "Death of Author," it is not necessarily authors whom give intention to text, but rather readers. With intention comes genre, especially in the Aim classification, which is why I grouped it at the highest levels of granularity. If we are to take the most popular tags at each level (Social Commentary, Human Nature, Psychology, Victorian, Urban), only a single text fits this depiction perfectly: Doestoevsky's The Idiot (188 overall, 10CR). We may perhaps state that this text is the most "expected" text on the AC; if there was such a thing as "Canon Bait" as there is "Oscar Bait" in the film industry, this text checks all the boxes.

Perhaps the more interesting conclusion at which we may arrive based on this data is that, more than anything, while we have favorites, we applaud diversity of text. Of all 407 texts examined through this taxonomic classification, only a single one ticked all the boxes. This proposition is alluded to, additionally, by the relative rarity of Adaptation on the AC (including only four texts: The Possessed, East of Eden, His Dark Materials, and Idylls of the King). An interesting debate then here appears, one which runs counter to my projections of canon relevancy in Chapter Two. Given both our propensity to shrug at adaptation and our appreciation of diversity, I wonder if there is only a single canonical "spot" for each classification of work, and, once filled, would we refuse to see any other work as anything more than a knock-off of the original? In other words, absent new genre classifications, can the canon be "complete," once all various genre options have been filled? (Note: for this to occur including only the criteria listed here (Aim, Theme, Subtheme, Aesthetic, Setting) we can use the "counting method" by creating a tree of options. This works out to be 17x26x11x23^2, or 2,571,998 combinations, roughly 5000 times larger than the AC as comprised. If we also include our other criteria not discussed in this chapter (Fiction/Nonfiction, Prose/Verse, Format, and Audience), this number grows to 2,571,998 x (2x2x7x3) or 216,047,832). This number is absolutely monstrous, of course; nearly two hundred twenty million texts is more than all the words in the AC as currently comprised by a factor of about 10. However, it is, however distant, an endpoint. If we were to exhaust all these possible titles with the "best" within each genre category, could we potentially consider the canon "complete?" Given the subjectivity involved in our taxonomy, as well as the time it would take to accomodate over 200 million texts, and not taking into account new genre classifications we cannot yet fathom, I do not believe we will ever reach this number, though the fact that the possibility may exist is fascinating.

As previously mentioned, the most common Aim within the AC is Social Commentary, with nearly one quarter of all texts looking to make a statement in regard to society in one form or another. Many of these further broke down into specific social issues, as Racism, Scandal, Social Class, Madness, Crime, and especially Human Nature, are all represented within this Aim. Ten of these texts tackle Racism directly (A Raisin in the Sun, Song of Solomon, The Bluest Eye, Invisible Man, Native Son, Uncle Tom's Cabin, Go Down Moses, Wide Sargasso Sea, Death Comes for the Archbishop, and Oroonoko), while a further five texts discuss the concept within the Subtheme of Civil Rights (Huck Finn, Heart of Darkness, The Last of the Mohicans, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Twelve Angry Men). Women's rights were also of specific interest for AC authors, even moreso than Racism. Fourteen texts dealt specifically with this subtheme (The House on Mango Street, The Story of an Hour, The Color Purple, Clarissa, The Bell Jar, The Yellow Wallpaper, Orlando: A Biography, The Bluest Eye, Wide Sargasso Sea, As You Like It, The Rainbow, The Awakening, and The Scarlet Letter). The next most common genre within Social Commentary was a mixture of anti-Colonialism and socio-economic criticism. Eight texts examined colonialism: Heart of Darkness, The Last of the Mohicans, Kim, Waiting for the Barbarians, Things Fall Apart, A Bend in the River, A Passage to India, and Rob Roy. Social class was also widely queried, with a number of texts within its ranks also readily classified as about race or sex if we desired to shift labels even slightly. These texts include: The Jungle, Sybil, The House by the Medlar Tree, The Black Sheep, Sartor Resartus, Atlas Shrugged, A Tale of Two Cities, Watership Down, The Satyricon, and His Dark Materials. In all, the number of texts dedicated to social activism is far higher than any other single genre.

Our next highest-scoring Aim on the AC was Tragedy. I will freely admit I do not appreciate a good tragedy as much as, apparently, fellow canon-list makers; while never a fan of it myself I can, however, recognize its appeal. There is a perception that authors frequently write about death, and the preponderance of Tragedy on this list bears that out. Beginning with the classic tragedies of the ancient Greek playwrights through the Shakespearean tradition, and including epic poetry and novels along the way, the tradition of tragedy in literature is quite well-supported. There are three trending tragic themes that show up repeatedly within the data. The first is the pairing of Tragedy with Human Nature (10 texts, Sister Carrie, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Dulce et Decorum Est, The Things They Carried, Of Mice and Men, Sophie's Choice, Timon of Athens, The Iceman Cometh, Doctor Faustus, and Clarissa). The second trend is the pairing of Tragedy with Revenge (14 texts, Hippolytus, Medea, Hamlet, Macbeth, The Duchess of Malfi, Froth on the Daydream, Julius Caesar, Ajax, Titus Andronicus, Agamemnon, The Nibelungenlied, The Bacchae, Prometheus Bound, and Libation Bearers). You will no doubt note the proliferation of drama, especially ancient Greek drama, within this particular genre pairing, suggesting that not only was Tragedy extremely popular in the time of Aristophanes and Sophocles, but especially revenge tragedy. The final tragic trend occurs with the pairing of Tragedy with Romance (14 texts, Troilus and Criseyde, Antony and Cleopatra, Romeo and Juliet, The Great Gatsby, The Wings of the Dove, Women in Love, A Farewell to Arms, Madam Bovary, The Sun Also Rises, A Streetcar Named Desire, Anna Karenina, Les Miserables, and The Phantom of the Opera). Other themes appearing within Tragedy include Scandal, Speculative Fiction, Magical Fiction, Intrigue, Madness, Ghost, Crime, Colonialism, Bildungsroman, Aging, and Adventure, suggesting that, if anything, our literature can make a tragedy out of any life circumstance, but, at least speaking literally, our most tragic endeavors are apparently revenge and romance. If this is not a commentary on the human condition than I don't know what is.

The Romance Theme, for its part, also runs the gamut. In addition to the aforementioned Tragedy, there are also twenty comedic romances, two entertainment romances, three experimental romances (Point Counter Point, If On a Winter's Night a Traveller, and Gravity's Rainbow), one horror romance (The Italian), two love romances (Lorna Doone and Evelina), one redemptive romance (Herzog), two reflective romances (The Glass Menagerie and Sons and Lovers), three satirical romances (The Female Quixote, Don Juan, and Zuleika Dobson), seven social commentary romances, and three tragicomedy romances (The Winter's Tale, The Pursuit of Love, and Vanity Fair). The treatment of romance, romantic interest, love, and marriage is usually at the fore of many of these texts, but it is equally true that a romantic story is often used only as the backdrop for another particular aim (for example, social commentary about women's rights or social class, love in wartime, etc). Even for as many texts that we see within Romance, however, it still comes far short of outstripping the most common theme within the AC: Human Nature. This broad theme is closely tied to social commentary (27 texts display this combination, the most common Aim/Theme combo on the AC), but there are also 19 texts that use Human Nature as a theme and Reflection as an aim, texts that examine the self, rather than the "other." Other Human Nature themes include Tragicomedy (1 text, A Confederacy of Dunces), Tragic Human Nature (10 texts), Satirical Human Nature (6 texts), Religious Human Nature (3 texts, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, The Screwtape Letters, and The Temptation of St. Anthony), Mysterious Human Nature (1 text, The Crying of Lot 49), Love and Human Nature (3 texts, Daniel Deronda, Le Grand Meaulnes, and Love in the Time of Cholera), Horror and Human Nature (2 texts, Deliverance and The Waste Land), Experimental Human Nature (5 texts), and Entertainment and Human Nature (3 texts, The Secret Agent, Nicholas Nickleby, and The Mysteries of Udolpho).

We have already discussed the least popular Aim on the AC (Adaptation), but Dedication, Tragicomedy, and Redemption all share the same respective low-tier ranking. Given our propensity for appreciating Tragedy, I expected Redemptive stories to appear at a much higher rate, at least proportionally, but it is not so. Evidentally, either we more strongly appreciate seeing people fall from grace, or, more likely, great literature is concerned with the lesson that may be taken from it, and the mistakes that lead to Tragedy are more readily taught in avoidance than the relative warmth of a feel-good redemption arc. The lowest scoring Themes on the AC include Various (used only for anthologies that made the genre cut), Metafiction, Whimsy, Worship, Legal, and Absurdism, all scoring at 1% of texts or less. Various is no surprise, as it is merely a collective category for otherwise unratable texts. Metafiction is often too strange to warrant high regard. Whimsy is relegated to Children's literature, of which there is little on the AC. Absurdism is much like Metafiction. None of these themes are surprising to see low on the list. The two surprises, at least to me, were within Worship and Legal. Worship is a theme which is associated with religious texts, but specifically the extolling of religious virtue rather than critique of it; the AC is filled with satirical, social, and harsh critique for religious worship structures (almost always Judeo-Christian). There are far less texts that extoll the value of religous virtue. There are 45 texts on the AC that utilize a Theological Subtheme (sometimes related to mythic religions or religious allegory), but, in contrast, only three texts (2 of which share the theology subtheme) use the Worship Theme. They are Antigone (which extolls the Greek Gods and punishes Creon for disobeying), Paradise Lost, itself a retelling of the Christian allegorical fall from heaven within Genesis, and The Divine Comedy, which is an exploration of Christian theological structures. (Dante and Milton share the theology subtheme, while Antigone is placed under the subtheme of Family. While Morality is a common subject amongst AC authors (21 texts), worship falls far, far, behind. Given the extensive history of worship literature, beginning in the first century AD and extending until present day, this was especially surprising. The other low-scoring theme that was surprising to me was Legal, which also only includes three texts: To Kill a Mockingbird, Bleak House, and The Merchant of Venice. Interestingly, even of these three, Bleak House depicts a legal proceeding that results in a tragic outcome, while To Kill a Mockingbird is far better remembered for its depiction of racism and The Merchant of Venice is similarly well-remembered for its antisemitism. Even texts that are set in courtrooms (4 texts, Twelve Angry Men, The Eumenides, The Trial, and Darkness at Noon) eschew legal themes in favor of mystery, crime, politics, morality, civil rights, and even foundational myth and experimental literature. Rarely, does it seem, that the justice system is worth literal discussion in and of itself, but it often finds itself the mechanism for telling other stories. This is my only conjecture.

Subtheme has three widely adapted favorites: Psychology, Society, and Theology. We have briefly discussed Theology as a subtheme for founding a new mythic religious practice, satirizing or critiquing an existing one, or as representative of the divine or divine transgression (such as in classic Victorian Gothic). Society we have also briefly discussed, usually in conjunction with Social Commentary, as a method of critique the mores, norms, and traditions of society itself (which society and which critiques vary according to author and time period). The true standout, however, is Psychology, accounting for 19.5% of all subthemes on the AC and representing almost 1 out of every 5 texts. As you might expect, Psychology is often paired with the Madness tag and the Human Nature tag, but also, surprisingly, the Crime tag as well. Everything from fear (The Raven) to violent tendencies (120 Days of Sodom) to hauntings (The Turn of the Screw) to sexual scandal (Lolita) to life lessons (Peer Gynt) is represented within the tag. Many of the texts that utilize the Psychology subtheme examine the nature of the human mind and human behavior itself, but others merely use it as a backdrop against which to write (for example, a mad character becomes a plot catalyst, or a normal psychological process, like how to deal with aging, becomes the plot catalyst). In general, Subtheme is more evenly distributed than are Aim and Theme, suggesting a more broad depiction of categories within its ranks, also represented by the large number of subthemes (second only to the number of Aesthetics).

Aesthetic, Setting, and Setting-EX

Aesthetic often doubles as "genre" for many. Calling a text a "Western," for example, automatically fills in many of the blanks in what to expect when reading. For our purposes, aesthetic includes not only typical symbolism and tropes found within each text, but also reflects the relative level of technological and civil advancement within the text. A text classified as Georgian, for example, many not necessarily have been written to occur during the reign of George III (1760-1820); however, it is designed to reflect the level of technological advancement available to the characters: pre-industrial revolution. It is also common for many Aesthetics to have been "founded" by a single text and then adapted into others. William Gibson's Neuromancer, for example, is emblematic of the "Cyberpunk" aesthetic, but is not the only Cyberpunk text on the AC (Ubik and Snow Crash being the others). You will likely note that aesthetic genres within literature are far different than those found in film, but much overlap exists. Film noir, for example, was quite common and popular in its day, but only three noir literary texts appear on the AC (The Big Sleep, LA Confidential, and The Maltese Falcon).

There are two very common aesthetics used in most AC literature: Victorian (urban centers post-industrial revolution, pastoral countryside), and Myth (magical, legendary and/or imagined aesthetics). The Myth aesthetic is quite common for Fictional settings, of which there are many on the AC, while the Victorian setting was, as previously noted, likely Contemporary for the authors that wrote within it. There are few, if any, Victorian period peices on the AC. Contemporary is our third most common selection, reflecting a culture that utilizes computer technology (no matter how rudimentary), but stops short of speculating about future technology (the domain of Sci-Fi, Cyberpunk, and Apocalyptic aesthetics). The fourth most common aesthetic, and one that surprised me, was Modernism, with 7.9% of all AC texts. For those unaware, Modernism is a specific literature genre and writing style pioneering by the likes of Joyce, Eliot, and Woolf, which focuses on stream-of-consciousness authorship, breaking the "rules" of language (such as ignoring spelling and punctuation), and focusing on early modern technology like early flight and and gilded age tech. WWI is typically a backdrop, as is the Great Depression and the Interwar period. For our purposes, WWII (the start of the Atomic Age) marks the end of the Modernist aesthetic and the dawn of the midcentury aesthetic. Interwar is our next most popular aesthetic, which utilizes the same technological level as Modernism but eschews the experimental writing style, followed by Midcentury, which occured just after Interwar. As you might surmise, these results are, again, a product of authors writing about the time periods in which they lived; the explosion of texts within the twentieth century is well-represented by the aesthetic choices made by various authors. For the most part, we may assume that the bulk of canonical work, at least through the lens of aesthetics, appears to be interested not in narrative structure but historical representations; we seek authorship and literature that helps us visualize the past through aesthetics, ourselves (through reflection and/or psychology), and the structures which govern our lives (religion, morality, politics, romance). In short, genre on the AC appears to be nothing more than a mathematical depiction of something we've long known: that literature reflects our culture and seeks to teach us lessons, through social commentary or tragedy, on how to better it.

Some of the least common aesthetics are also, by no coincidence, the most specific. Superhero has only a single text (Watchmen, arguably Midcentury), Western has only two texts (Death Comes for the Archbishop and My Antonia), Prison boasts four texts (The Count of Monte Cristo, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, The Beggar's Opera, and "The Pit and the Pendulum"), Noir contains three texts (listed previously), and Cyberpunk contains three texts (listed previously). If there is an antidote to the aforementioned conundrum of "finishing the canon," it will likely be found here, within Aesthetic. Since Aesthetic is so closely tied to technology and cultural tradition, I find it likely that new genres, especially more specific ones, will continue to crop up and extend the canon for as long as we see fit. Whether or not you want to finish the canon, however, if you believe it is a "good thing" to do so, is another debate entirely.

Far and away the most common Setting within the AC is Urban. 31.4% of all texts, almost one out of every three, uses a city as a backdrop for its events. This makes logical sense, as interpersonal conflict and communication is typically the basis for good literature, and this type of interaction is more readily found where there are more people, ie., urban areas. We may also surmise, however, given authors' apparent propensity for writing exactly what they experience, we may also conclude that the vast majority of writers lived in urban areas. Biographical and historical research bears this out, and we are left to wonder if the canon has been skewed by authors writing from such locations. In other words, considering the import of the canon itself on learning within university and casual settings, has the tendency of authors to live in urban areas affected our learning style in modern times? It is an interesting proposition, for sure, but one which I cannot unfortunately answer. The second most common setting was Travel, indicating texts in which the events occurred over a large scale of locations, typically multiple urban locations, potentially raising the urban count even higher. Mythic was next, reflecting imagined and legendary locations, while Domestic came fourth, usually the setting for short drama and short stories. The Domestic tag was often paired with the family tag and/or the inheritance tag. Fifth was War, used as both setting and, more often, backdrop for a multitude of stories (nearly one in ten). At the bottom of the Setting list are Christmas (one text, Dickens' ubiquitous A Christmas Carol), Fourth Wall, characterized by strange surrealism (four texts, A Modest Proposal, Pale Fire, Finnegan's Wake, and If On a Winter's Night a Traveller), Courtroom (4 texts, previously mentioned), and Outer Space (seven texts, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Little Prince, Dune, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Foundation Trilogy, The Martian Chronicles, and Neuromancer, which could also readily be classified as Urban, Mythic, or Travel, save for the final act).

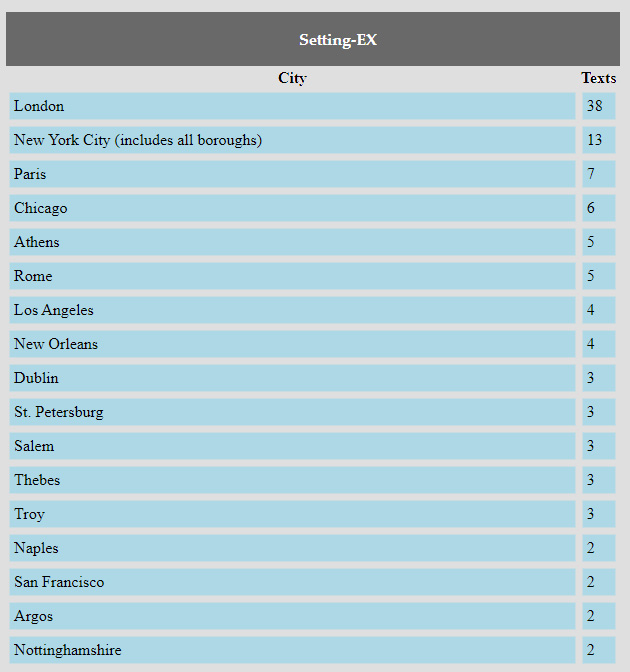

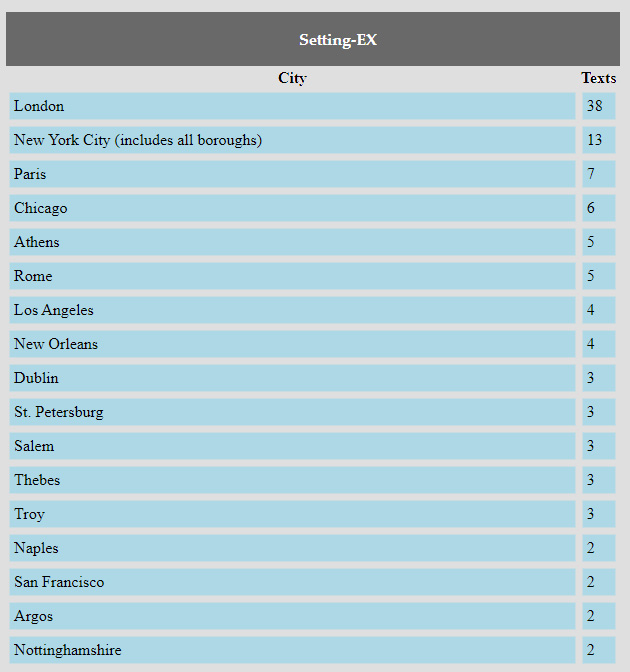

Given the ubiquity of the Urban setting, then, the next query I asked (data not included in the above charts) was: "Since the city is the most common location for AC texts, which city reigns supreme as the most common real-world city within literature?" The answer likely won't surprise you, but I will explicate the data here using a category called Setting-EX, or Extended Setting. When we set aside Fictional settings and focus only on real-world locations, the city that rises to the top, by a wide margin, is jolly old London. With a whopping thirty-eight texts set on the shores of the Thames, London is far and away the highest-scoring location within the AC. No other city even cracks double digits, (only New York City does, and only if you include texts set specifically in Brooklyn as being set in New York City) and London is the second-most common setting within all settings on the AC, behind only all fictional settings grouped together. The chart below illustrates other notable urban locales within the AC.

Note that special consideration should be given within Setting-EX to the fictional city of Jefferson, Mississippi, USA. The favorite setting of Faulkner's universe, nearly all of his works were set there (or in the surrounding, equally fictional Yoknapatawpha County). The rest of the real-world locations within the AC are set only generally by state, country or even continent (Alaska, Kentucky, India, Africa, Germany, Ireland, Italy, etc.), or are cities that are featured as settings in only a single text on the AC. Those cities are, in alphabetical order, Algiers, Antwerp, Arden, Bath, Bedfordshire, Black Hawk, Boston, Boulder, Bristol, Cephalonia, Chancellorsville, Cincinnati, Concord, Corinth, Devonshire, Dover, Dresden, Dumfriesshire, Ephesus, Essex, Exmoor, Glasgow, Glendale, Gorizia, Hampshire, Havana, Highbury, Honolulu, Kyoto, Lemnos, Madrid, Malfi, Maycomb, Messina, Milan, New Bedford, Northamptonshire, Oran, Oslo, Oxford, Oxfordshire, Padua, Parma, Pianosa, Rouen, Segovia, Seville, Shanghai, St. Louis, St. Petersburg MS, Suffolk, Sussex, Tarrytown, Tashkent, Transylvania, Troezen, Tulsa, Venice, Verona, Vienna, Wessex, and Yorkshire. Note that some locations are either fictional or fictionalized versions of their real-world counterparts, often with exaggerated populations, a common technique for most texts set in the UK.

Conclusion

This analysis leaves us with a number of conclusions. From the Aim tag we recognize that social activism is not only alive and well on the canon, but is also the most strongly-propagated major textual concept, followed by tragic text and, in a smaller block, entertainment and comedy. Lessons, it seems, come before leisure. From the Theme tag, we recognize that we are strongly interested in ourselves, as Human Nature leads the pack, but also interested in one another (as it is followed by Romance) and the world around us (third on the list is Adventure). From the Subtheme tag, we recognize that, again, we are fascinated by ourselves and our systems: Psychology, Society, Theology, and Politics, in descending order of popularity. The Aesthetics we prefer are either Victorian, Contemporary, Modern, or Mythical, and the list of Aesthetics is constantly growing, fragmenting, and evolving. Finally, from the Setting tag we note that Urban is by far the most common setting for a text (specifically London), followed by Travel, Mythic, Domestic, and Wartime settings.

This chapter examines the AC in terms of genre. As you may know, genre is a loaded, subjective, ill-defined term which seeks to act as a grouping system for texts within it. The function of these groups may be stated to act as a guide for the reader, setting an expectation as to the type of content within the text. As Daniel Chandler notes in An Introduction to Genre Theory: "Genres can be seen as a [system of generic expectations, or a code]...which amounts to a shorthand serving to increase the 'efficieny' of communication" (7). Chandler utilizes Fowler's definition of genre code, and explicates on it as a means of "shorthand" to understanding textual implications. He further notes that "Defining genres may not seem particularly problematic but it should already be apparent that it is a theoretical minefield" (2). He goes on to quote over a dozen various scholars' points of view on genre itself, ranging from how genre can be used to stifle creativity (7) to a more nuanced, modern view espoused by Gledhill, Fowler, and Rosewater - namely, that "Restrictions breed creativity" (Rosewater GDC), (Chandler 7). He describes how "Conventional definitions of genres...are [constituted] of content (such as themes or settings) and/or forms (including structure and style)" (2). Bordwell, another genre scholar specializing in film text, mentions that "...no set of necessary and sufficient conditions can mark off genres...that all experts or ordinary film-goers would find acceptable" (147), and Chandler, amidst a wide-ranging discussion of purpose (another ill-defined term), notes that "How we define a genre depends on our purposes" (3).

This chapter examines the AC in terms of genre. As you may know, genre is a loaded, subjective, ill-defined term which seeks to act as a grouping system for texts within it. The function of these groups may be stated to act as a guide for the reader, setting an expectation as to the type of content within the text. As Daniel Chandler notes in An Introduction to Genre Theory: "Genres can be seen as a [system of generic expectations, or a code]...which amounts to a shorthand serving to increase the 'efficieny' of communication" (7). Chandler utilizes Fowler's definition of genre code, and explicates on it as a means of "shorthand" to understanding textual implications. He further notes that "Defining genres may not seem particularly problematic but it should already be apparent that it is a theoretical minefield" (2). He goes on to quote over a dozen various scholars' points of view on genre itself, ranging from how genre can be used to stifle creativity (7) to a more nuanced, modern view espoused by Gledhill, Fowler, and Rosewater - namely, that "Restrictions breed creativity" (Rosewater GDC), (Chandler 7). He describes how "Conventional definitions of genres...are [constituted] of content (such as themes or settings) and/or forms (including structure and style)" (2). Bordwell, another genre scholar specializing in film text, mentions that "...no set of necessary and sufficient conditions can mark off genres...that all experts or ordinary film-goers would find acceptable" (147), and Chandler, amidst a wide-ranging discussion of purpose (another ill-defined term), notes that "How we define a genre depends on our purposes" (3).