The Early Years: Prehistory and Classical Greek

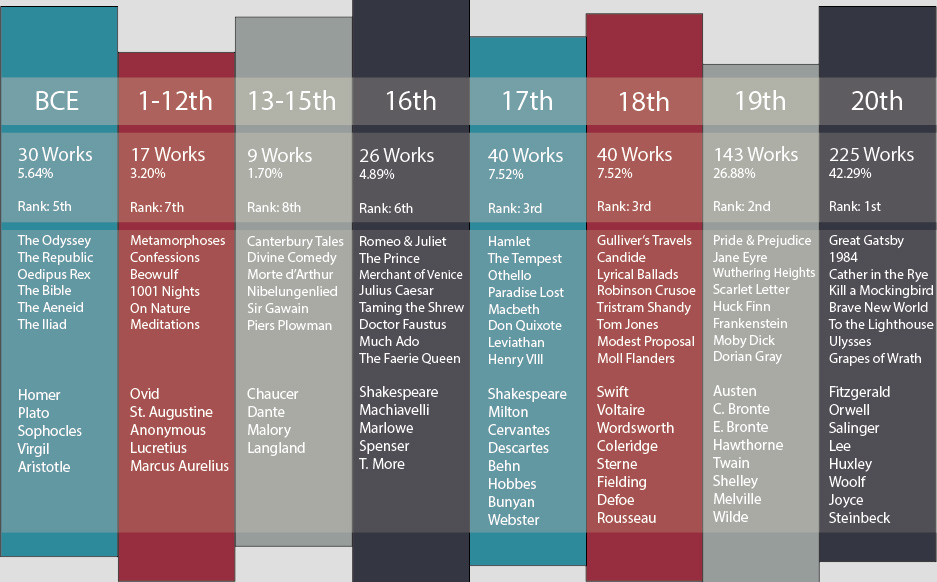

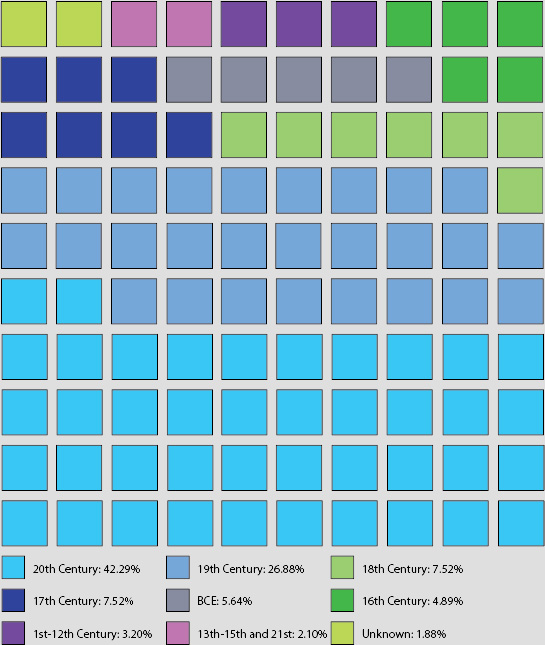

The AC hosts a total of thirty texts that span from the dawn of literature until year 0 on the Julian calendar. When dealing with eras this far into antiquity, all dates are approximate, many authors are unknown, and even countries of origin are lost to the mists of history. Every attempt was made to identify correct time periods and "publication" dates (although that term means little in this era), sometimes even using an average of several sources. Overall, this time period ranks 5th overall in AC contributions, with the bulk of writing occuring during the Classical period of Greece. The era's most popular author was Homer, racking up 72CR between two entries, the expected Iliad and Odyssey. The most popular text from the era also belonged to Homer, with the Odyssey scoring 43CR, enough to place 12 overall. It was not, however, the highest-scoring epic or verse; that honor went to Dante's Divine Comedy, which, with 48CR, scored a finish of 9th overall. Other popular authors from the period were Sophocles, Plato, Euripides, Aristophanes, Aeschylus, and Aristotle. It is worth noting here that many of the most popular playwrights from this time period, including those previously mentioned, have vast tracts of "lost works" for which only fragmented sections, or in some cases, only titles, have been found. Matthew Wright in The Lost Plays of Greek Tragedy notes that, for example, Aeschylus alone had 71 individual texts, of which only seven (or six - authorship of Prometheus Bound is disputed) survived. Four of these plays appear on the AC (Agamemnon, Prometheus Bound, The Eumenides, Libation Bearers), though if we had surviving fragments of the rest, his contributions would likely be far higher. We may assume the same for other Greek tragedians, meaning that if we had all of the lost texts from these authors the era of Prehistory would contain far more texts than it does, likely raising its profile from 5th overall to as far as 3rd or even 2nd. Considering the lack of publication technology and difficulty in making and producing copies of texts from this time period, we might even consider the works of these authors to be the most influential on all the Western Canon (that is, until Shakespeare, of course).

The most prolific author from the time period was Aristotle, with 8 contributions to the AC, though his CR pales in comparison to even the more modest authors from this time period. Much of the writing within this period are tracts on mathematics, art, poetry, statehood, and religion, though the most popular works, as perhaps expected, are dramas and epics. Even in antiquity, it seems, we had a fascination with the fictional. Interestingly, no authors from Greece made the AC after this time period, suggesting that after the Classical period ended, translators were unable, or unwilling, to bring these texts to the canon, and as such they never captured popular attention. It was during this period, also, that perhaps the greatest destruction of literary texts occured, a literary tragedy of unknowable impact, with the destruction of the Library at Alexandria. In addition to Ptolemy VIII Physcon's purging of intellectuals from the city of Alexandria in 145 BC, Julius Caesar accidentally burned a part of the library during the Roman Civil War in 48 BC. This began a decline in the library's membership and stewardship, which eventually culminated with its completed destruction in ~265 AD. It is difficult to say how different the AC would look - or, Western Civilization, for that matter - had the manuscripts at Alexandria survived.

This period accounts for 5.64% of all works contributed to the AC. The oldest text within the period, and the oldest on the AC by far, is The Epic of Gilgamesh (196 overall, 9CR), first published ~2100BC by an anonymous author, while the most recent is Virgil's Aeneid (47 overall, 27CR).

Roman Classical and Early Medieval: 1st-12th Centuries

The AC hosts 17 texts from this time period, 3.20% of the AC total. While this number is greater than the least scoring time period (13-15th centuries), the fact that it spans 1200 years instead of only 200 makes this time period the in which the least literary output eventually found its way to the Canon; that is, the lowest Canonical density may be found in this era. This epoch is primarily dominated by Roman writers, including Marcus Aurelius, Ovid, St. Augustine, and Lucretius. The most popular text from this era was St. Augustine's Confessions (62 overall, 24CR), followed closely by Beowulf (81 overall, 20CR). Further extending the tradition of the Greek period in prehistory, most of the texts from this era are nonfiction treatises and essays on philosophy, politics, religion, and morality. This era seems to be the origin of religious doctrine divorced from myth, for while myth remained popular (as evidenced by Ovid), St. Augustine's text seems to be the first that openly references the new religion of Christianity (~400 AD). Rome's first Christian emperor was Constantine, who ruled ~280-337 AD, demonstrating the sea-changing effects the Christian religion had on Roman culture, world culture, and, of course, literature. Other religious texts also date from this era, including the Qu'ran (~614) and Metamorphoses (AD 8), perhaps the last great work in which foundational creation myth and theology were closely intertwined. Later centuries would see authors reacting to these texts (like Chaucer, Langland, and Malory, amongst others). It is obvious from the textual publications found on the AC that theology, in the form of both "faithful writings about" or "critical responses to," dominated both literature and culture for the better part of almost 1300 years.

Anyone with even a passing familiarity of history will likely see the trend beginning to develop in regard to the texts adopted to the AC. A vast tract of texts (many unfortunately lost to history) sprang from the ancient Greek Classical period, and a large additional number, primarily focused on adherence to novel religions, began to usurp them during the reign of the Roman empire, which lasted for centuries in one form or another. The next epoch, the 13th-15th centuries, saw great famine, plague, and worldly upheaval just before the dawn of the Early Modern Age. Fittingly that time period has the fewest texts of any, as well as the second-lowest literary density. A rough parallel may be drawn from not only the number of texts produced, but also the number of canonical texts produced, between human quality of life (quantified as free time dedicated to persual of the arts) against time spent on subsistence. The relatively low output and literary density from the 1-12th centuries becomes more difficult to explain, then, unless we assume either a lack of education for the common populace (a likely scenario), or perhaps the warlike nature of the Roman empire exalted other persuits. This is all, of course, merely speculation.

The Late Medieval: 13th-15th Centuries

The upheaval that gripped the globe in the late medieval period is difficult to overstate. In addition to the Great Famine (1315-1317), the Black Death obliterated entire populations of Europe. Endemic warefare, including the Hundred Years' War, Jacquerie, and the Peasants' Revolt further decimated the continent. It is perhaps no great surprise, then, that artistic flourishes essentially ground to a halt before the world began to enter the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery. This firmly entrenches the time period in its expected place as the least contributory era to the AC, including only 9 texts (1.70% of AC total). Only four known authors wrote during this period: Chaucer, Dante, Malory, and Langland; all other AC texts from this era were published anonymously. It wasn't until Shakespeare burst onto the scene almost two hundred years later that literary output resumed levels not seen since antiquity with the onset of the Early Modern Age. Despite its relatively small contribution, however, the 13th-15th centuries play host to two of the most lasting, and highest-scoring, texts on the AC: Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (4 overall, 53AC), and Dante's Divine Comedy (8 overall, 48CR). Only the 19th and 20th centuries place as many texts within the top ten as this era, which, as stated, is astounding, considering its low output. Canterbury Tales was easily the most popular text from this era, with Dante not far behind. The only other texts from this era to appear on the AC were Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (249 overall, 4CR), Langland's Piers Plowman (283 overall, 3CR), Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (122 overall, 15CR), and anonymous texts Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (294 overall, 5CR) and The Summoning of Everyman (372 overall, 3CR). Historically speaking, even Chaucer and Dante, the era's "representatives," published in 1390 and 1320, respectively, are placed near the tail end of the time period, closer to the establishment of the Renaissance. Fascinatingly, the very end of this time period, 1436, saw the development of Gutenberg's printing press by building off of ideas and technologies of movable type and wood block printing pioneered by the Chinese and Koreans several centuries earlier. The contribution this invention had to the world of literature was positively massive, and no technology until the computer and the internet has done as much for the proliferation of literature since. With Gutenberg's invention increasingly available as the calendars flipped, it is no surprise, then, that the following century saw literature increase in popularity within the AC.

The Early Renaissance: 16th Century

The Renaissance and the Age of Discovery covered the early half for the 16th century with new ideas, technologies, and innovations. Within the world of literature, the rate at which new texts were developed and adopted was relatively slow, but accelerated near the end of the century to a level not yet seen since the Classical age some 1600-2000 years prior. The early half of the 16th century saw primarily texts that were in line with those from the late 15th century: nonfiction, treatises, essays, and other documents that sought to examine philosophy, statehood, and religious affiliation. It wasn't until the tail-end of the 16th century, when a certain William Shakespeare made his presence known, that the contents of the AC really began to take off. It's been stated previously how much of an influence Shakespeare had on the canon, and we might perhaps pinpoint his works, even moreso than, for example, the development of the Gutenberg press, as the "launching point" for the canon. This time period is responsible for 26 works added to the AC (4.89% of total), with most of those contributions coming from Shakespeare himself (and a few from his contemporaries, Marlowe, Donne, and Spenser). This century wasn't especially noteworthy outside of his contributions, but as the first, it certainly set the stage for what was soon to come.

We might, perhaps, if we were inclined to separate the canon into consitutent canons by date of publication, use this century as our "turning point," as the Early Modern period which begins here not only sees a massive proliferation in number of texts but also a diversity in textual content. By this time, the tragedy still reigned supreme (owing to the Greek tragedians and Shakespeare's more popular work, though much of his most popular work would wait until the 17th century), as did drama and epic poetry. You'll undoubtedly note a distinct lack of novels thus far; those come about a hundred years later. We could, therefore, pinpoint this era as the turning point from ancient texts (tragedy, theologic, epic, verse, myth, and foundational/religious) to more modern fare (novels, fiction, narratives, social commentary, theologic repudiation). Whether or not you believe this era (and Shakespeare in particular) marks the end of the ancient era or the beginning of the modern one is up to you. A further delineation of the canon might perhaps take place near within the 19th and 20th centuries, as the texts on the AC seem to suggest another shift in general content and format, though this might also only be an example of recency bias, or it might mark the dawn of a new literary era, in which we may subsitute "Gutenberg Press" with "Internet." Only time will ultimately tell.

The Late Renaissance: 17th Century

The early half of the 17th century was again dominated by Shakespeare, who died in April of 1616. Much of his work from this century was published posthusmously with the First Folio, which contains more single works in the AC than any other anthological publication in the history of literature, yet another testament to the playwright's greatness. The latter half of the century began to see further development in religious writing and fiction, as well as an extension of already-established formats the Epic (with Milton's Paradise Lost), the treatise (with Hobbes' Leviathan), and, perhaps most importantly, the development of what some consider the first ever novel, a format that would take over not only the literary world but the canon in general: Cervantes' Don Quixote de la Mancha. The literary output from this century was, as you can see, beginning to grow. The expected "explosion" of works wouldn't come until almost two centuries later, but the groundwork was being laid and extended and many non-Shakespearean classics were in line for future addition to the canon. This century, in total, saw 40 works added to the AC (7.52% of total), and set a new record for most works added during a time period. New communication technology was in place, education, ideas, and thoughts abounded, and although the world continued to see war and poverty sporadically, the darkest of times in the 13th-15th century had been steadily replaced. The future, as it were, was looking bright. It is no coincidence that historians often label this period as "Early Modern European History," as culture (and, by extension, literature) began to take a familiar shape during this century.

I've mentioned the printing press several times to this point, and it is indeed true that the technology enabled authors to produce works more readily and quickly than ever before. More telling, however, as previously stated, is the relative leisure time individuals might devote to writing. Although things in this era are vastly improved from the relative hellscape that was the 13th-15th centuries, the explosion of literary output finally occurs in the 19th century; not, as it were, thanks to an improvement in communication technology, but rather, the industrial revolution, which increased quality of life for innumerable people and created dedicated leisure time for millions. If there is a single advancement in the history of mankind that has done more for literary progress than any other, it would have to be not the printing press or even the internet, but instead the industrial revolution. In Chapter Three, when we discuss demographics, you will also notice that increased trade and flow of ideas (geographically speaking) led to the development of literature and canonical works. The communication technologies of the printing press and the internet undoubtedly assisted this process, but the ability to think, write, and work unfettered is the single greatest indicator of literary output (and, if the AC is accurate, quality). Tragedy and conflict might make for good stories, but only those who survive to tell those stories make good literature.

The Early Modern Period: 18th Century

Not to be confused with Modernism, a literary movement that wouldn't come around for another two hundred years, the Early Modern period of the 18th century continued where the 17th century left off. Interestingly, both centuries contributed the exact same number of texts to the AC (40, 7.52% of total). This time period's most popular author was finally, after two hundred years of dominance, no longer Shakespeare. Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels reigns supreme during this century (20th overall, 38CR), with Voltaire's Candide (44 overall, 27CR) and Wordsworth and Coleridge's Lyrical Ballads (46 overall, 27CR) close behind. Wordsworth and Coleridge, in particular, was one of the first, "modern" poetry styles to be adopted into the AC. Although the Epic verses of Homer, Chaucer, Marlowe, and Milton were still present, Wordsworth and Coleridge carved out a niche which saw future poets extend verse into new and exciting areas (although, once again, we may trace the first widely-adopted of this type of poetry back to Shakespeare and his collected Sonnets). The novel, too, was continuing to see evolution and progression. Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (66 overall, 23CR), Sterne's Tristram Shandy (51 overall, 17CR) and Fielding's Tom Jones (47 overall, 18CR)all saw publication during this time period. The format was well on its way to utter dominance, and while the most popular format of the time was the epistolary, that was soon to be eclipsed by the newcomer. This century also saw the evolution of some of the more famous and enduring thematic literary aesthetics, including Romanticism and the Gothic, the latter of which began with Horace Walpole's 1764 publication of The Castle of Otranto (199 overall, 9CR), and reached its AC pinnacle with Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights (7 overall, 49CR).

Popular topics for authors during this era were philosophy, science, and politics, as Rousseau's Social Contract, Smith's Wealth of Nations, Hume's Human Nature, Newton's Principia Mathematica, Berkeley's Principles of Human Knowledge, Lavoisier's Elements of Chemistry, Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, and the founding documents of The Federalist Papers, The Declaration of Independence, and The United States Constitution demonstrate. All saw publication during this period. Fiction texts were often either Gothic, as previously mentioned, and the budding new genre of the novel, which would explode in popularity in a century's time. You will undoubtedly note the shift in content amongst nonfiction authors from an interest in theology to one in the sciences and philosophy, mirroring the advancements of the Classical age; not unusual, especially considering the Gothic, the most popular fiction genre of the time, was also interested in the long-lost mists of Classical ruin and architecture.

The Age of Industry: 19th Century

The tail end of the Romantic age of literature brought with it a transition into the industrial revolution, and, later in the century, the Gilded Age. As previously stated, this revolution cannot be overstated in the impact it had on literature, culture, and thought. Further refinements in communication technology, coupled with the technology's newfound ability to harness electricity, steam power, and coal engines, brought about further education and dissemination of text. New ideas, building from older ones, and a higher standard of living (which resulted in less time fighting costly wars and struggling under famines) all added up to more time in which individuals could read and write for a living. As a result, despite continuing major conflicts (the Napoleanic Wars, for example), literature flourished. Reasonably, we could construe this century as the expected outcome of two hundred years of progress following Shakespearen lead; or, we could acknowledge that the industrial revolution had more of an impact on lives and literature than we had previously thought (my personal opinion). Whichever the case, literary production absolutely exploded. With a staggering 143 additions to the canon (26.88%), the 19th century brought almost as many works as every time period before it combined. In only a hundred years' time, the canon quite literally doubled in size, going from 162 works in almost 1800 years to 305 works in a little under a hundred. Led by the number one overall entry into the AC (Austen's Pride and Prejudice, 60CR), the century sees more authors in the top ten of the AC than any other, including Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre (3 overall, 55 recs) and Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights (6 overall, 50CR). It also places more works in Tier A than any other (24; the next closest being the 20th century with 23).

It was in this time, too, that American authors began to really take off alongside their counterparts across the pond. Given the American Revolution fought in the final two decades of the previous century, it was no surprise that American authors' contributions really began to shine here. Gone were the days of early American authors like Washington Irving, and in were the days of popular American authors like James Fenimore Cooper, Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau. Meanwhile, in the UK, the Gothic novel continued to prevail as the most popular genre, with authors like Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Gray, 22 overall, 37CR) taking hold, alongside the newly-budding genre of speculative science fiction with Shelley's Frankenstein (16 overall, 42CR), incidentally, the most-assigned text in university syllabi today (opensyllabus.org), and the ever-growing genre of adventure fiction (usually with a feature of social commentary) led by Joseph Conrad. Other luminary British authors of the time included Charles Dickens, George Eliot, and Lewis Carroll, while the list of translated works grew to include Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Tolstoy, Ibsen, and Nabakov. The most popular scientific paper on the AC, Darwin's Origin of Species (76 overall, 21CR), also originated in this century.

It is no surprise, given the veritable cornucopia of texts floating about, coupled with the rise of American authors, that we perhaps colloquially consider the 18th century the pinnacle of literary studies, and certainly representative of the type of texts that are called to mind when picturing literary scholarship. Its popularity on the AC certainly speaks to this, as it occupies, if less texts overall than the 20th century, at least a series of respectively higher rankings, including two of the top three, three of the top ten, seven of the top twenty, and twenty-four of Tier A (33.8%). One also must consider that the AC in total is perhaps a primarily American institution, considering the proliferation of American authors within (representing 51% of all authors present) in only two hundred odd years' worth of contributions. Whether this is due to recency bias or merely the transformative nature of the industrial and American revolutions (ie. "right place, right time") is unknown.

Finally, we begin to see the novel finally take it's place within the 19th century as the format of choice. Although the popularity of the novel may perhaps just be due to its emergence during the time in which the greatest number of texts were being written and added to the canon, we may also consider it something of a "chicken or the egg" problem, and instead note that, just perhaps, the canon may not have exploded in the manner in which it did if not for the proliferation of the new format.

The Modern Era: 20th Century

The explosion of literature continued, well into and through the 20th century, and showed no signs of slowing down. Again, despite major upheaval (two World Wars), literature proliferated unabated, at a speed heretofore unseen in human history. Adding a whopping 225 works to the AC (42.29% of total), the 20th century ranks first overall in terms of texts added. It contains the highest-output decade in the entire canon (the 1950s) and the highest-output year (1953). Much like the 19th century just before it, the 20th century nearly doubled the canon in size again, growing from 305 works in 1899 to 530 by the turn of the milennium. At the time its texts were added, if we ignore the texts themselves, the 20th century alone accounted for a 73.7% increase in canon size, second only to the 88% increase offered by the 19th century. American authors dominated once again, with F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby leading the way (2 overall, 57CR), and Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye (15 overall, 42CR) and Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird (18 overall, 41CR) not far behind. Other luminary authors, pioneers of the modernist movement (which took hold of literature after the turn of the century), included Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, and James Joyce. American classics from John Steinbeck and William Faulkner burst onto the scene, providing a haven for modern tragedy and domestic fiction alike. Drama continued it's powerful literary tradition with playwrights Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. Dystopian fiction got its start as an outgrowth of speculative fiction, seeing authors like Orwell, Vonnegut, Huxley, and Bradbury rewrite the future. Social commentary reached new heights alongside the American Civil Rights movement, fueled in no small part by famous literature from Ralph Elison, Zora Neale Hurston, Harper Lee, Lorraine Hansberry, and W. E. B. Du Bois. The wake of the Civil Rights Movement provided further, more recent canonical additions from authors like Toni Morrison and Alice Walker.

In short, the 20th century was a fracturing of "great literature" into smaller, more specific, more nuanced genre categories, each with its own luminary authorship and texts. This literary diaspora simultanesouly explains the nature of the 20th century canon (more texts, with relatively smaller CR scores), each more directed and niche than the texts before. No longer was there the "next great novel"; rather, authors identified audiences and wrote what they knew to those audiences, resulting in individualized, but altogether passionate, fan bases. This mimics, as you'll no doubt note, the university system of today, in which there is no "literature" class, but rather a series of fragmented literary study courses, each focused on a genre, author, demographic, time period, or other facet of modern literature. Because of this process, it is my speculation that no text will ever unseat those at the top of the AC, as "universal acclaim" appears to be a relic of the 19th century, and in its place we have texts that are preferred more passionately by a relatively smaller subset of scholarship.

Interestingly, the vast majority of 20th century works are selected from the early parts of the century up until roughly the 1970s. The most prolific decade on the entire AC, the 1950s, was at the height of the American Civil Rights Movement, and saw twenty-eight texts added to the AC in a mere ten-year span, the highest literary density on the entire canon, and three times as many texts in a single decade as in the years from 13th-15th centuries. They are, in order from earliest to latest by year: Wouk's The Caine Mutiny, Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, Lewis' The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, Jones' From Here to Eternity, Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye, O'Connor's Wise Blood, Williams' Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Steinbeck's East of Eden, Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea, Ellison's The Invisible Man, Barthes' Writing Degree Zero, Baldwin's Go Tell It On the Mountain, O'Connor's A Good Man is Hard to Find, Miller's The Crucible, Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, Beckett's Waiting for Godot, Golding's Lord of the Flies, Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Nabokov's Lolita, Wiesel's Night, Rand's Atlas Shrugged, Cleever's Wapshot Chronicle, Kerouac's On the Road, Achebe's Things Fall Apart, Bellow's Henderson the Rain King, Burroughs' Naked Lunch, Camus' The Possessed, and Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun. One would be hard-pressed to find another decade as prolific as this one (28 texts, 272CR), though there are a few contenders. The 1960s (28 texts, 191CR); the 1940s (30 texts, 244CR); the 1890s (20 texts, 275CR); the 1850s (19 texts, 295CR), and the stiffest competition, the 1920s (27 texts, 339CR). Ultimately, despite seemingly higher figures, I discounted the 1920s as the "best overall decade" as 57 of its 339CR came from a single text (The Great Gatsby), meaning the 1950s, on average, has a higher CR/Text score, as well as more texts in the canon overall.

The Future Era: 21st Century and Beyond

The AC is host to only two texts published after the dawn of the 21st century, both relatively low on the list: Cormac McCarthy's 2006 text The Road (452 overall, 1CR; incidentally, the newest addition to the AC), and W. G. Sebald's 2001 text Austerlitz (383 overall, 2CR). As the 21st century is still quite relatively young, time will tell if these texts gain in popularity or remain static. Whatever the case, it seems as though most list-makers exclude texts that are too recent in memory; perhaps as an attempt to avoid recency bias, or because the weight of tradition is simply too strong. With the addition of these final two texts, the AC reaches its current iteration of 532 current entries. Because of the nature of this project, once a text enters canonical status, even with only a single CR from any source, it will not be removed. Reasonably speaking, this list will ultimately, eventually, grow to become too large and unwieldy (though the argument may be made that it already is)! At that point, it will likely be necessary to cull the list of single-rec texts or even dual-rec texts, if this project were to be redone at a later date some years in the future.