![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

Getting Power from the Grid There is an odd imbalance in the culture of philosophy of science. We are exceptionally accomplished at filtering out and destroying poor ideas. That is the traditional activity of a talk. A speaker presents some new ideas, nervously, and the audience attacks. Only the strongest survive. Where do these ideas come from in the first place? We have no comparable institutionalized system for generating them. That omission is the imbalance we are expected to produce new ideas in the reflective solace of our offices by some private magic that we absorb silently from the walls. This is unlike what I have seen in other communities with which I have intersected. These other communities have developed management techniques that foster the creation of new ideas in communal meetings. Why do we not use these same techniques? Our material may be loftier, but our problems are no harder and our minds are no smarter. And we are not beyond needing help. Part of the reason for the omission may be that the techniques can be undignified. One needs to create a playful environment in which our normal, self-critical shields are lowered. Part of the reason may be that these techniques do not work that well. A hard afternoon's work may only net one or two good ideas. However I suspect the biggest reason is that we just do not think to try them. We are now in the middle of the second term and I judged that this year's cohort of Fellows had developed sufficient community to sustain the experiment. I'd floated the idea earlier over dinner at a Chinese restaurant after our reading group; and last week we had agreed to try the experiment. Now we were getting ready for the meeting. I'd promised an authentic cheese log. But Trader Joe's did not carry it. They lean towards cheese as opposed to compounded cheese products. I thought we could manage with a fragrant St. Andre and a salty, hard Dutch cheese whose name now escapes me. The method I'd proposed depends on two ideas. First, is that odd juxtapositions can produce important novelty. Imagine wings flying underwater and you have a hydrofoil. Move an airplane's wings only and you have a hovering helicopter.

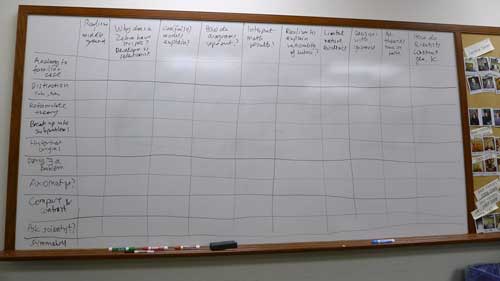

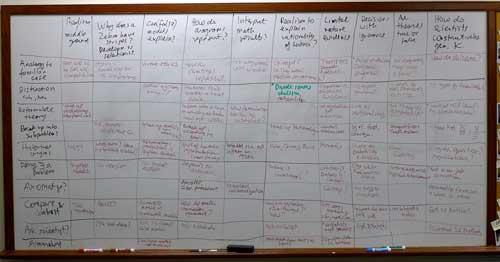

Yes, it does exist and it is quite... well, interesting. The proposal was not to pair tastes, but to pair problems in philosophy of science with methods that we have seen work. I'd asked everyone to come with one of each. I was eager to start since I knew we'd need lots of time. But first we needed to plan next week's agenda and that took almost half an hour. The process began. I started going round the room, recording each person's problem across the top of the white board. With a second pass, each person contributed a method. They went down the board. There were ten problems and ten methods: 10 x 10 = 100. That gave us one hundred grid squares on the white board. Our goal, I announced, was to fill each square. I'll admit that at this point my spirits were flagging. There had been greater and lesser levels of enthusiasm among the Fellows about this plan from the start. Things were now dragging. We were an hour into our two hour meeting and had yet to see a single novel thought. It was a difficult moment as I scanned over the room from my place at the whiteboard. We began to fill the squares, one at a time. I fell into the steady refrain: "Pick a box. What will you put in it?"

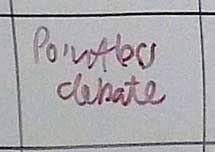

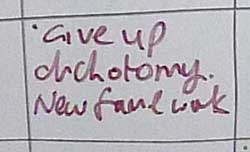

In one box, this problem intersects with the method "Deny there is a problem." That was now filled with a simple idea. The whole realism-antirealism debate is on a fake issue, a pointless debate. Give up trying to mediate between two bad ideas. "Hmm," I thought, "There's something to that, but it is severe." Shortly after, the "Reformulate the theory" box was filled. Forget about realism and antirealism. Focus on what makes each attractive in so far as they are attractive. Find a new framework tailored to whatever that is. "Yes," I now thought, "that's a better direction. What do I want the representational success of science to do for me? What do I want the fictionalism of antirealism to do for me? Otherwise, forget about representational success or failure." We proceeded clockwise round the table, fill a box, fill a box, fill a box. It felt painfully slow. I was giving up the idea that we could fill them all. My target was now the one and half hour mark. I'd halt the process there, for better or worse, and ask everyone to pick their favorites for further discussion in the last half hour. If we had a good discussion in the last half hour, then maybe everyone would forgive me. I was trying to perceive what had gone wrong. What I might have done differently? What repair was possible? Should I apologize now for wasting everyone's time? But I could only pause momentarily for these reflections. My time and attention was fully committed, passing from person to person round the table. The grid was filling. The minutes ticked away and the time arrived. We had half an hour left. "Shall we pick our favorites now?" Then something remarkable happened. Or at least it had already happened, but so slowly that I hadn't noticed. There was a new fluidity to the filling of the boxes. The proposals were arriving faster and more compactly. There was momentum here. Anxious that it was over too soon, Dana had one more box to fill before we stopped. And Michael said, "let's go another round." I could now see what I'd missed. They were all alternatively listening to the new proposals and also scanning the empty boxes. There was a now familiar rhythm to it. The boxes had become little challenges. They were like the half filled squares of a crossword on the kitchen counter, an open invitation to whoever passes. It is too easy to huddle over it and fill one more square; and then one more. It was getting easier, Leah told me afterwards. She was listening to the other proposals so that when her turn came she had to throw out something quickly just to keep things going. Bacon and chocolate?! Why not?! Your turn. This was how it was supposed to go. When we started, it had been hard to keep up the pace. We are not used to making proposals in only a few words. But now they were coming. "Read Carnap!" Someone declared for one box--and then only one sentence was needed to explain why. At the two hour mark, we would normally stop and take a break before heading off for dinner. But at this two hour mark, we were sitting back admiring the grid. We had not filled it completely. But we were three fourths there. I counted 75 proposals in the grid on 100. Not bad coverage! A spontaneous assessment began. Look at the "compare and contrast" row. That really is a powerful method. Look at the "generate knowledge" column. We seem driven to seek outside help from the scientists. It seems we don't have enough ideas within our literature. The assessment continued and we passed five minutes, then ten and then more into overtime. There was a warm sense that we had achieved something communally. No one wanted to walk out on the after-party. "It worked!" I thought. If I had any doubt, Adrian asked if I would circulate the photo I was taking of the whiteboard so that everyone would have a record. Nils-Eric was leaving nothing to chance. He too was taking a photo. I'm now quite looking forward to next week's plan. Michael Tomasello is sensing a mismatch between the basic ideas used by philosophers of the physical and those of the social sciences. He'd noticed that we have a good mix of the two types in the room and that is a resource to use. He and Uljana promised to assemble a list of terms: theory, hypothesis, explanation, … They will be circulated ahead of the meeting. We will go through them and find out just what they really mean. John D. Norton |