![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

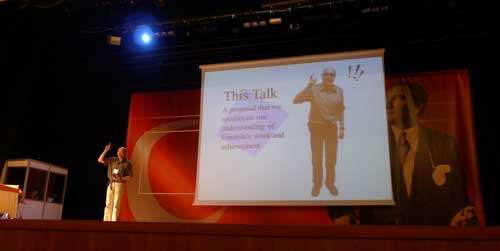

"Back to the Source" Every four years, past Fellows of the Center for Philosophy of Science assemble for a reunion conference. The tradition is well established. Our past meetings have been in Athens, Ohio (2008); Rytro, Poland (2004); Bariloche, Argentina (2000); Castiglioncello, Italy (1996); and more. We can hear the latest ideas in philosophy of science. We can catch up with old friends and make new ones in the Fellowship of the Center. It is also something more. A visit to the Center is a vacation from the daily routine of a professor to another place. While visiting in Pittsburgh, a Fellow is surrounded by philosophers of science and immersed in philosophy of science. This environment is a stimulating source of novel thought and a memorable experience. The conference is a chance recapture and relive a little of it. This year, our meeting is at Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University in Turkey. Muğla is in Southwestern Turkey not far from the ancient city of Miletus, where philosophy was born. This is the city of Thales, who appears in our histories as the first philosopher. He first practiced that peculiarly effective mode of thinking we call philosophy. We were traveling back to the source. None of this would have been possible, however, without the efforts and hospitality of Muğla University. Mehmet Elgin opened to the doors to this hospitality. We had first talked of the possibility of this conference in the Spring of 2008, when Mehmet was a Fellow in the Center. We were chatting idly in the Center's lounge. Such chatter is often the beginning of greater things. I still recall how his eyes lit up with the idea. I thought then that he'd taken to it with the comfort of an accomplished organizer. It was only later, in the middle of the conference, mellowed by the conviviality of after-dinner speeches, that he admitted just how much the idea had terrified him. He was right to worry. It is a big and complex event. We have 48 speakers and their entourages, coming from over 20 countries. They all need to be transported, housed, and fed. And they were in great comfort, thanks to Mehmet's efforts and those of his many helpers. These included the graduate students of his department, who labored hard behind the scenes. Towards the end of the conference, I wandered by as they were photographing each other in the main foyer of the conference center. It was the happy moment in which they realized that their efforts had been successful and that memorable time was about to end. They agreed to pose for me as well. I'm not sure if everyone is in this photo, but many are. Our own tireless Center organizer, Bryan Roberts, is also posing in the group. The program of talks was large and covered many topics. There were two talks specifically commissioned by Muğla University to be more popular, in the sense that they should be accessible to a wider university audience. They were to be simultaneously translated into Turkish by translators sitting in a glass booth to one side of the stage. One was Peter Machamer's. He had promised to speak on the topic of "Mechanisms and Mechanical Explanations." That seemed to assure some quite predictable fare. Peter, always looking to throw us just a little off balance, had managed to befuddle me completely when I read his abstract. It says: "O bliss, bliss and heaven! Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise, silver-flamed and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again, crunched like candy thunder. It was like a bird of rarest spun heaven metal or like silvery wine flowing in a space ship, gravity all nonsense now. As I slooshied, I knew such lovely pictures!" With that abstract in mind, I settled down in my chair to hear Peter speak with a little more than ordinary curiosity. I soon heard familiar ideas. Peter reminded us of his 2000 paper, "Thinking about Mechanisms," with Lindley Darden and Carl Craver. While there was little danger that we had forgotten, he reminded us that it had secured the position of the most cited paper in philosophy of science for several years. "That's the journal Philosophy of Science," Peter allowed, "not the whole field." There was a need, Peter told us, to save the expanding literature on mechanisms from doctrinal deviations. That correction would be part of his burden today. What followed was Peter at his magisterial best. He recounted for us once again how the orthodoxy correctly understands mechanisms. He was drawing his distinctions as carefully as the Pope when he speaks ex cathedra. I'll admit that my level of understanding of the literature on mechanisms is not rich enough to be able to discern the invisible hazards around which he navigated. However I did notice that Peter managed to include three illustrations of mechanisms each connected with wine. In a lighter aside, he confessed that he was not all that invested in the term "mechanism." However, "if it had been Machinism…" The other invited talk was my own, and I'll mention it simply so I can justify showing a nice graphic. Over fifty years after his death, Einstein has become a universally identified symbol of wisdom in science. He was justly honored as "Person of the Century" in the December 1999 Time magazine cover. My concern, however, is that this attention has turned Einstein into a visionary who somehow anticipated the next 100 years of physics. While there is a case for Einstein's far-sightedness, my talk sought to reveal a different Einstein. It is a 19th century Einstein. For, once one looks for it, one finds much of his science, methods and outlooks are 19th century. There were many more talks. The program lasted for three days. At its most dense, there were four parallel sessions running for a full day. It is not possible for me to survey the richness and breadth of the talks. You will need to visit the program and see for yourself. The city of Muğla is a quiet, rural administrative center with a little over 50,000 inhabitants. It sits in a rocky, mountainous part of Southwestern Turkey that feels curiously spacious and empty after the few days we had spent exploring the tumult of Istanbul. The city has been energized by the establishment and building of the University in 1992. We held our talks in its new conference center. It has large modern auditoria, furnished with the latest technology. As are most public buildings in Turkey, every room was equipped with edifying portraits of the founder of modern secular Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. I would have liked to spend more time exploring the campus. However the weather had turned very hot during our visit. Temperatures rose quickly in the 90's F and a fierce sun beat down. My tolerance for this weather seems less than the average. I found the five minute walk in the midday heat from the conference center to the cafeteria debilitating. It was worth the walk, however, since the lunch served was superior to anything I'd eaten at a University cafeteria. The fare was traditionally Turkish. Our first lunch was minced meat cooked with peppers, tomatoes and eggplant, with freshly baked bread. The only failing was the curious decision not to air condition the cafeteria, which made it impossible to recover from the heat of the walk. Muğla is up in the mountains at an elevation of around 670 meters. Mehmet had arranged for us to stay in the village of Akyaka on the nearby coast of the Aegean Sea. Akyaka is about a 20 minute drive from the campus of Muğla University. The steep descent affords tantalizing glimpses of the coast and the town. When we arrive, looking back past our hotel, we find the mountains towering over us. Akyaka is a delightful little coastal village. One can walk across it in five minutes. When we make our way into it from the outskirts, we find all the signs of a small fishing industry. Then there were clear signs that fishing was giving way to a more lucrative industry, tourism. Mixed in with the fishing boats are small tour boats. And then we burst onto a full-blown, bake-in-the-sun beach culture. The talks are the focus of the conference. However they are surrounded by something that is just as important. We Fellows of the Center are a community and we remain a community only if we meet to refresh our bonds and forge new ones. This most important part of the conference happens in the coffee breaks over Turkish cookies, in leisurely dinners and in quiet moments sitting by the hotel pool after the heat of the Turkish summer's day has passed.

Mehmet organized what proved to be a quite extraordinary excursion for us. He'd told us of a boat and an island and suggested that we take swimsuits. We weren't quite sure what was in store for us and we were quite happy to leave the details to Mehmet. On Wednesday afternoon, when lunch was over, we returned to Akyaka and assembled outside the hotel, with our swimsuits, if we had brought them. The sun was still high and the air fiercely hot. After the hot bus ride, I was roasted, stewed and overcooked and I did not welcome the short walk down to the town's dock. It passed quickly and soon we were boarding a small boat. We could sit on the lower deck in shade or on the upper deck in the full sun. Eve needed no clue from me to know which to choose. The boat was ummoored, the anchor weighed and our bow was pointed towards the Aegean Sea. We were soon leaving the town of Akyaka behind. Once we were out on the water, a cooling breeze sprang up and blew over the shaded deck of the boat. It was refreshing and calming. We sat at tables while a lady served us cool drinks and small, strong glasses of strong Turkish tea. We soon fell into the idle chatter of people who know that they will sit just here on this bench looking out over the water for a while and then a while more.

These shores and waters look the same today as they did a thousand years ago and ten thousand years before that. The few other boats we passed might well have been time travelers who had somehow sailed back millennia. Or perhaps we were the time travelers. These are ancient waters of legend. They have been navigated by sailors for thousands of years. Troy is just a little way up the coast. The Greek fleet would have sailed near here on its way to do mischief at Troy. Ulysses may well have navigated into this bay on his long voyage home. Perhaps he had stared out at these very same rocks as the steady breezes drove his ship onward. They look just the same now as they did then. And he would have welcomed the cooling breeze that filled his sail just as we welcome it now. The thought was comfortable and natural. At that moment, had Ulysses himself sailed by, the sight would have given us only a momentary pause before we turned back to our cups of tea. Our destination was Sedir Island, also called "Cleopatra's Island." It is a small island just an hour or so of sailing from Akyaka. Gereon Wolters secured its history from the best source, the lady who had been serving us tea. He took the microphone and told us the story. Cleopatra herself had come to this island and there decreed a beach. It was to have the finest sand brought in from Egypt and strewn over the coarse rocks. This fine sand was the secret of her beauty and we could beautify ourselves by rolling it. However all wonders have their limits and no sand may leave this beach. We must wash it off before we leave. We moored at the small dock on the island and set off for the beach. There was a ten Turkish Lira admission fee. Presumably it is a new obstacle Cleopatra did not need to pass. We followed a long, wooden boardwalk over the dunes to the small, spare beach. There was little else there, beyond a few items of beach furniture and few small sheds, housing changing rooms and the like. Otherwise the island was surely just as it had been in Cleopatra's time. Alas, her unique beauty was to remain unchallenged. The precious sand had been cordoned off and we were not to roll in it. A security guard sat nearby, watching, just to be sure. We gazed over the shallow water. It was turned a pale green by the yellow sand of the sea bottom. I could almost see the lithe figure of Cleopatra gliding through this water. She looked curiously like Elizabeth Taylor with badly overdone eye makeup. We soon joined her. The water was cold enough so that we lost our breath with the first plunge. The cool water drew out the heat of our bodies and worries from our thoughts. It was so refreshing that we were reluctant to leave. I only learned later on the boat that I'd missed seeing the ruins of an ancient city and a temple of Apollo elsewhere on the island. Given the choice of hot stones or cool water, I'd choose the same again. On returning to boat, I paused to read the official tourist sign of the island. It affirmed what I'd suspected; and it was reaffirmed by reading elsewhere. There was no mention of Cleopatra or the shipping of sand. The small, exquisite deposits had quite another source. It was all to do with carbonates from fresh water and things called oolites and pistolites. It was good to learn that later and not sooner. We returned to Akyaka just as the day was drawing to a close and the light was growing pink and red. Mehmet had arranged dinner for us and the familiar buses took us for a short three-kilometer drive. It would be fish by the river, he told us, bass. Eve and I had eaten the most exquisite fish sandwiches in Istanbul on the quayside of the Golden Horn, just next to the Galatan Bridge. A man stood in the baking sun of a carpark with a small grill. As we watched, he would throw a fish onto the grill, cook it, debone it, pile it with trimmings and squeeze it into a sandwich. I was expecting something similar. Perhaps our destination would be a modest shed by the river with a grill; and we would cluster around munching our sandwiches. When the bus stopped, I knew how far my imaginings were from the reality. We passed through an entryway and found an elegant restaurant literally in a small river stream. We crossed a small bridge onto an island covered with tables. We settled down at them and awaited the steady stream of food and wine that busy waiters brought us. The fish was perfectly cooked and delicious. One by one we gradually noticed something I've seen in no other restaurant in the world. On the opposite bank of the river, fifteen or twenty feet from the nearest diner, stood a wild boar. It wandered up and down the bank. Menacing as its tusks looked, it proved to be domesticated and waited for the diners to throw it scraps of food. We obliged.

John D. Norton |