![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

Wesley C. Salmon Memorial Lecture

It is now a decade since he left us. His legacy lives. It is in the minds of those who read his work and in the hearts of those who knew him, wherever they may be. The idea for a lecture series in Wes' honor came from outside the University, but it was warmly embraced here. It is a fitting testimony to the reach of Wes' legacy that three units of the University collaborate to bring about the series: the Department of Philosophy, the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, and the Center for Philosophy of Science. None would cede a role.

The important message conveyed by their words was the respect and devotion given to Wes by all who knew him. I cannot repeat their words and stories here and hope to convey that sense. It is lost when others retell the stories. So I will take a liberty and tell my Wes story. From it and many more, I learned that greatness can come from the accumulation of many small kindnesses. ------------------------------

Such are the illusions of a junior professor who is thinking more of his tricks than his readers. Someone had to tell me. That someone was Wes. He did not summon me to his spacious office. He just dropped by my cramped quarters and sat in the chair that was squeezed in at the end of my desk. I knew something was up. This was not usual. My chapter was, he assured me, technically wonderful. I heard the words, but his body language told me he was troubled. That pain grew more visible as he continued. Then finally came the blow, plainly and simply: "It's too hard." I can still see the moment vividly. He had leant forward for emphasis. He slumped back into the chair, a heavy, horrible weight having lifted from his shoulders. I knew instantly that he was right. I'd really known it all along, but now there was further motivation. He had to be right or this painful exercise through which Wes had just passed would be a huge mistake. Over the next month or two, I set about fixing the chapter. What resulted was a greatly improved piece. I did not expect Wes to think about the matter again. He'd done his job. It was an editorial trifle of the type that appears daily when one works at Wes' level. Many months, perhaps even a year later, he reappeared in my door. He was teaching a class with a student who just wasn't getting it. That student's struggle was bothering Wes. Nothing he could do was getting through. Then, he told me with a smile, the class read my chapter. That finally worked. The student came to him beaming. "Now I get it," he reported. Wes was beaming at me and, at that moment, I was happy beyond all cares. ----------------------- It is no easy matter to select a speaker who can do justice to Wes' legacy. So we commissioned a nominating committee of Wes' students, chaired by Ken Gemes. They recommended Elliott Sober, who now stood before us. Sandy Mitchell did her best to convey just how distinguished our speaker was. But we already knew. The room was filled with as many chairs as we could find; and each chair was occupied. Then Elliott gave his tribute to Wes and turned to the content of his talk. Elliott's goal was to develop some ideas concerning causation in the tradition pioneered by Wes. His teacher, Hans Reichenbach, had introduced the common cause principle as a way of identifying causes. Wes had developed and propagated the idea.

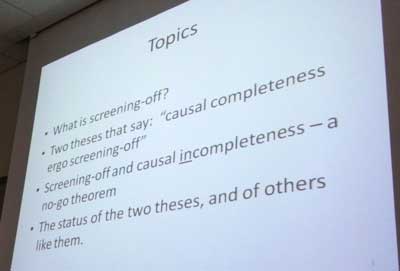

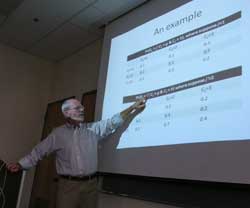

The details of Elliott's development need not concern us here. Briefly, he had a new theorem relating multiple causes and screening off. He led us to it in a carefully calibrated series of steps. We were all soon engrossed and an energetic discussion period followed. I was too engrossed then by the talk to realize what I now see is the highest praise I can give to the talk. Wes would have loved it. John D. Norton |

Wesley Salmon holds a special space in our community of philosophers of science. His work on explanation, causation and more exercised a profound influence on the work of a generation. His personal example inspired his colleagues and students. We became better people for knowing him.

Wesley Salmon holds a special space in our community of philosophers of science. His work on explanation, causation and more exercised a profound influence on the work of a generation. His personal example inspired his colleagues and students. We became better people for knowing him.

Decades ago, the Department of HPS set out to write a departmental textbook. I was given the job of writing the chapter on philosophy of space and time. I took to the task with gusto, inventing all sorts of ingenious pedagogic tricks to convey the latest excitements. The result was, I was sure, a masterpiece of pedagogy. How proud, I thought, my colleagues will be to have this in the volume.

Decades ago, the Department of HPS set out to write a departmental textbook. I was given the job of writing the chapter on philosophy of space and time. I took to the task with gusto, inventing all sorts of ingenious pedagogic tricks to convey the latest excitements. The result was, I was sure, a masterpiece of pedagogy. How proud, I thought, my colleagues will be to have this in the volume.