![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

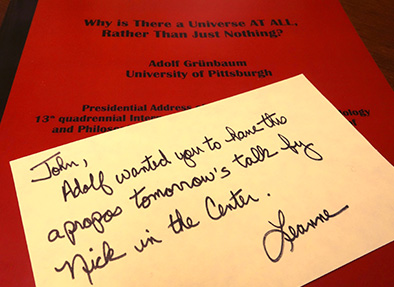

Ultimate Explanation There was little in the morning to indicate that today would be a most unusual one. We had some sandwiches left over from an earlier meeting. They were put out in the lounge for anyone who may wander by. Soon there was a small gathering in advance of the lunchtime talk. The mood was quiet and lazy. Our tradition is that Nick Rescher gives the first talk of the term in the lunchtime series. Today is that day. After the usual formalities, Nick began to speak. It was a curious start. He was more self-effacing than usual in his introductory remarks. This new year is an odd numbered year, he said, so he has an odd paper. He was going to ask a strange question; so we should expect a strange answer. We might attribute the strangeness to the speaker, but he hoped we would recognize it as really coming from the nature of the question itself. The question is the venerable question that, I believe, goes back to Leibniz. "Why is there something, rather than nothing?" That question immediately drew my attention. It was not so long ago that Adolf Gruenbaum had given a talk on just this question in the same room. Adolf would surely not be pleased with what was now unfolding. A clue that this was so was an item that appeared in my mail the day before. It was from Adolf, via his secretary, Leanne. The envelope held an offprint of Adolf's "Why is There a Universe AT ALL, Rather than Just Nothing?" The question is dangerous. As it happened, Nick immediately backed away from the danger. He was, he assured us, really interested in a slightly different question: "Why are things the way they are and not otherwise?" I was now paying more attention to Nick's demeanor. His habit is to read his talks. Few of us read talks and that is for the better, since few of us can read them well. Nick is an exception. He reads at a comfortable pace and with intonation that carries his meaning well. There was something different today. The words were coming too quickly. Nick seemed a little uncomfortable at the podium. Perhaps he had too much content for the time. Or perhaps there was something more. Where was this talk going, I wondered. It is for the better, I began to think, that Adolf is not in the room. He will never know what was about to transpire here. At that moment, Adolf walked in. He shuffled to the front of the room--he will celebrate his 90th birthday this year. He took a seat right under Nick's podium and arranged his paraphernalia on the table in front of him. This was something I had not expected. The event was turning into a major moment in our history. Let me explain. The Center has two eminences grises, the two co-Chairs of the Center. They have been teaching and researching philosophy of science in Pittsburgh since the 1960s. They built the philosophical ground from which the Center sprang. On some issues, our two eminences have very different views. Adolf pursues his atheism with an evangelical passion widely known across the philosophical universe. Nick is the president of the American Catholic Philosophical Association. In my decades in Pittsburgh, I could not recall any occasion in which they had faced one another publicly on these issues.

What would happen now? I watched Adolf as he listened patiently.

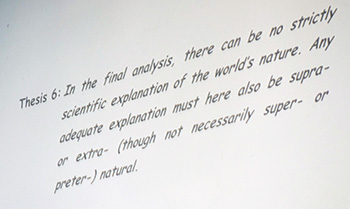

Nick's argument was laid out with extraordinary care. He developed it with a series of theses, ten in all.

Each was displayed with an old-fashioned overhead projector while he addressed it.

Novice that I am, the metaphysical waters through which he sailed appeared clear and blue. Yet the delicate succession of tacking and running in his ten theses showed that Nick was navigating past submerged shoals and reefs that I could not see. At the risk of running straight into one of those reefs, let me summarize Nick's argument. It has two phases. First, the question of why things are as they are cannot be answered from within science itself. For science proceeds from the facts, laws and principles that are true of our world. Any effort to explain why this world is the way it is, would be circular, if it calls on those same facts and laws. We must seek the explanation outside science. But where is it to be found? To answer, Nick entered the second phase, recalling the traditional distinction between fact and value. If not fact, it is through values and the metaphysical principles attached to them that we find the explanation. I was now getting out of my depth. I don't really know how a teleological/axiological explanation can work. There was no suggestion of a God making things just so for His purposes, or at least no explicit mention of it. That was a relief, for that line of argumentation appears facile to me. Rather the argument seemed Leibnizian, as one would expect from Nick. He has devoted a lifetime of scholarship to Leibniz. Our world is the way it is because it is the best of all possible worlds. The value resides in the "best." Our world is the way it is since it best realizes these values, whose precise character remainder elusive, or at least they did to me. Later in question time I pressed Nick on just how that value is to be understood. It is not the ordinary sort of human value which prizes comfort and well-being. It is to be understood in terms of intelligibility. It is present in those wonderful moments in human history when we achieve a deep understanding. Nick mentioned Archimedes in his Eureka moment. The universe will be such that it promotes beings capable of this understanding, of modeling the nature of things in thought. This Leibnizian notion was brought to the twenty-first century with Nick's summary: ours is "a user-friendly cosmos." Nick normally speaks with a drink close at hand. Perhaps he was distracted by the critic who sat immediately in front of him. In an awkward moment, he tipped his iced tea. As he mopped it up, he quipped that it might not be immediately apparent to a speaker who spills his tea that this talk is being given in the best of all possible worlds. Nick now drew his talk to a close. There are critics of this approach, perhaps even in the room, he said, with the irony missed by none. Those critics, he continued, would dismiss the question as inappropriate or meaningless. To this he would offer no refutation. "You pay your money; you make your choice." The talk was over. The audience broke into those who stretched, those who sought out a bagel, or more coffee, or a donut, or those who just sat and waited. Nick and Adolf began to talk. I drifted towards them to eavesdrop. It was "Will o' the wisp" metaphysics and ultimate explanation. This exchange was the most interesting part of the event. When it was over, I asked Nick if they would replicate it for us all at the start of question time. Nick agreed, looking puzzled initially that we would care to hear it. When question time started, he invited Adolf to speak.

Nick gave his reply. How can the regress of explanation halt? Will we eventually arrive at the ultimate premise of the deepest level that cannot be explained because there is nothing deeper? He had another model, which he built in the air for us with gestures. Perhaps there is this ultimate premise, but our analysis never gets to it. We approach it closer and closer and the distance diminishes arbitrarily. The analogy is to pumping air out of a vessel in an effort to achieve a perfect vacuum or accelerating particles ever closer to the speed of light. The goal in never reached, but we can get as close as we like. So it is with explanation. We can come very close to the ultimate premise, but there is always something more to support our last presumptions. We never base our explanations on premises that cannot be further explained. After Nick had responded, Adolf had one further question. What of the question "Why is there something rather than nothing?" That, Nick replied, was not his question. His was "Why are things as they are?" The floor was now opened to questions and they proceeded with as much vigor as ever. But somehow the event was over for me. I had heard that long ago the Titans fought heroic battles. Now I had been on the battlefield and seen the fray. It was a great deal more cordial than I had envisaged.

John D. Norton |