![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

Choosing the Future of Science: The Social Organization of Scientific Inquiry Kyle Stanford is our Senior Visiting Fellow this year. In one sense, it is an easy job. He just comes here and does his senior thing; and he gets to use our resources to run the conference of his choice. However it is also a hard job and that is the part that is difficult to define. He is to have a presence as a senior-sage-in-residence. He should mentor the more junior fellows who need wise counsel on the many little bothers that, on first encounter, feel like mammoth woes. He should also help our visitors transform from a disparate bunch of strangers into mutually-supporting community of scholars. In all this, Kyle has excelled. When junior scholars get the first of many internally contradictory referee reports, it is disquieting. Who better to guide them than one of the editors of Philosophy of Science, as is Kyle? He has mentored gently and wisely; and our communal transformation has happened quickly, in part due to Kyle's quiet but effective shepherding. He has provided a model of a supportive scholar in all ways... excepting management of speaking time. Last week, I was not able to attend our reading group meeting. Kyle managed to relocate it to a bar with a very fine beer selection, The Sharp Edge. No doubt the discussion was less sharp as the evening wore on, yet reports were that the discussion was still good. This was a real success of community building. The division between scholarly engagement and convivial camaraderie has quite disappeared. When Kyle's year is over, I will miss him. He is an astute discussant and has a quite unique, joyful presence. It is punctuated by a colorful style of speaking and asking questions.

For his conference, Kyle chose the topic of the social organization of science. I was quite happy to go ahead with it. Kyle, I had no doubt, would choose well and he made the topic sound interesting and important. However I do--or did--have a default bias against the topic that extends back into my history. When I studied for my PhD in history and philosophy of science in the late 1970s, sociology of science was entering into energetic engagement with HPS. Of the few graduate level courses I took, one was in sociology of science and another in science policy. In the end, they were discouraging experiences. The former seemed to be in a decline. The latter seemed transparently self-serving for the ambitions of its practitioners to sit on government committees. What was the problem with sociology of science? I'd found an earlier tradition with names like Merton and Ben-David to be interesting and informative. However it was then coming to be eclipsed by the so-called strong programme in sociology of science. Its central thesis was that the content of science was "socially constructed." That is just fancy academic speak for saying that the scientists are either making it all up or perhaps just deceiving each other into thinking they've made discoveries. Science is reduced to a self-congratulatory exercise in group-think. There were, of course, all sorts of clever academic arguments for the claim. But it seemed quite apparent to me from the start that purely sociological analysis cannot answer the question of whether science is succeeding at its epistemic goals. One must also give some sort of epistemic analysis. It was dismaying to me that people in my new profession would take these ideas seriously. Were they working out some animus against science? Were they consciously trying to deceive us? What? That experience tainted any connection between science and sociology for me. It was not helped by the subsequent emergence of "social epistemology." The variety of social epistemology most closely associated with HPS seemed intent on propagating a sociologically based skepticism. It was hidden in the new jargon. "Discovery," with its connotation of epistemic success was replaced by vaguely disparaging euphemisms like "knowledge production," with the connotation of scientists as sweaty laborers in some factory churning out cheap aluminum ashtrays. Perhaps Kyle sensed this when he decided there was a need to prepare us for the conference. The week before, he and Kevin Zollman gave a pair of talks on the social structure of science. (Photos) We subsequently read Kyle's manuscript in our reading group. That re-awakened my interest in the social aspect of the organization of science. Over the last century, science has become a communal activity in which we rely on our peers in many ways. That reliance, Kyle argues persuasively, has put a brake on our communal creativity. Our papers are more likely to pass peer review and our proposals are more likely to be funded if they agree with existing consensus among the reviewers. That cannot be good. All this reminded me a lot of Slobodan Perovic's concern that the concentration of experimental particle physics into a few very expensive particle accelerators might stifle discovery.

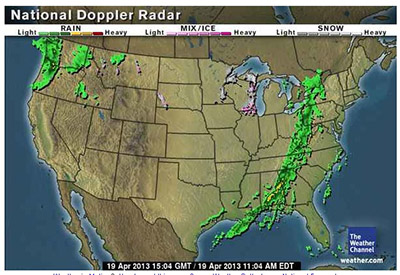

As the conference approached, we suffered the usual anxieties. An ugly band of storms blew across the continent, stranding at least one participant flying to the event. Here's the radar map from Friday:

Here's Kyle meeting with the staff and organizers at the same time. And here we are trying to figure out if Skype or Google Hangout is the best way to connect with a distant speaker. In the end we used neither.

I was ready to re-engage with the project of understanding the communal aspect of science. Just how would that understanding appear? It was tough enough to get clear on the working of science when considering just the lone scholar, the "Robinson" on his island of Philip Kitcher's talk the previous day. We were now dealing with a problem at least an order of magnitude more complex and that must call upon many skills and perspectives.

The first speaker was Michael Strevens. When things go well, in Michael's view, a simple mechanism in science allocates the scientists' efforts optimally. Since they are rewarded in their discoveries according to their personal contributions, there is always an incentive for a few scientists to take on some less promising lines of research. The worry, however, was that this mechanism could break down and too many scientists would work on too few lines. That is "herding." Michael catalogued the ways this might come about. Scientists might overestimate the promise of a program merely because they see many of the herd pursuing it. Or they may underestimate an explanatory program because it has little prospect of exciting, novel prediction. It was a comfortable discourse for a philosopher to hear. It proceeded at the familiar general level with a series of appealing arguments over how scientists would surely behave if they found themselves in this or that situation. However, as the talk proceeded, I began to get a little uncomfortable. There were no examples from science. It was all general talk. And the behaviors supposed for scientists reminded me of the "Just So" stories decried by my colleagues in philosophy of biology. The scientists or biological organisms might reasonably be supposed to do such and such. However, we really should do more than suppose. We should go out and test. They are both empirical issues.

I was curious if anyone else had similar reservations. Kyle fielded the flood of questions. One after another came and went without raising my worries. Then Kyle inserted himself into the queue and asked for an illustration of some claim. Michael gave a sentence or two describing a tension in cognitive psychology.

Elihu Gerson's talk was the second of the morning. He is a sociologist, he emphasized at the outset. His methodology was quite different. He would make no normative judgments at all; they would appear at best as data. Elihu reprised how various scientific specialties are defined: they persist; they reproduce; they have systems of peer review, of patronage; and so on, in many aspects. This, I recognized immediately from my earlier encounters, was elementary sociology, a rapid Sociology 001 for the philosophers. Where philosophers feel their first obligation is to delineate their theses and their arguments, sociologists feel compelled to articulate precisely the sociological group under investigation. "Biologists" is too vague a term to be the subject of sociological investigation. Instead we might look to that group that has appointments in departments labeled biological, that publish in certain journals, belong to certain societies, and so on. The main content of Elihu's talk was to use these methods to delineate two new structures in science, platforms and junctures. Platforms are organizations that make some collection of entities, techniques or procedures available for use by many in the broader community. An example is the provision of drosophila model organisms. Junctures arise when multiple lines of research overlap to form a relatively stable sociological structure. "Evo-devo"--the intersection of evolutionary and developmental biology--is a larger scale example. What was distinctive in Elihu's exposition was that it was densely illustrated by mention of many different subspecialties of science. They were mentioned, but scarcely elaborated. However we were left with a sense that the analysis was based on a serious look at many sciences.

Might the philosophers and sociologists come together? Perhaps, eventually. But there was a chasm evident between the two communities. I realized that some were hearing the methods of sociology for the first time. "Do people who use modus ponens form a platform?" That was a philosopher in question time asking after the cogency of the definition.

He had failed to see that Elihu would only include some group in his analysis if he could list numerous characteristics in common. It was an elementary misconnection. The equivalent in the reverse direction would be to ask a philosopher if some minor, chance pleasantry was a philosophical thesis.

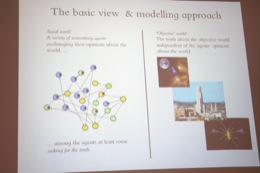

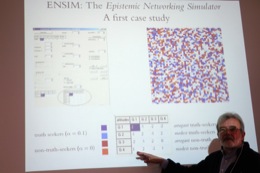

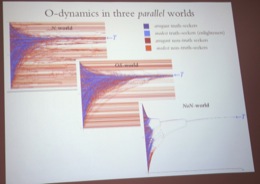

The third talk by Rainer Hegselmann brought another methodology to bear on the problem. It derived from an interesting property of communities. Each individual may relate to others in a few simple ways. Yet the community as a whole may manifest rich and interesting behaviors much more complex than that of any individual. How might this effect apply to science? Might we find a communal intelligence arising from some simple interactions among scientists? Agent based modeling is a new and thriving tradition in philosophy of science that aims to explore the effect through computer simulations. It might find behaviors that traditional conceptual analysis cannot, for the latter uses notions tuned to the cognition of individuals. The particular question Rainer addressed was how networking among scientists may affect their communal convergence to true results. The scientists become units in a computer simulation. Each is attributed a belief state that is really just some function over possibilities. Those belief states are then updated. Even with powerful computers, one can only get a tractable simulation if one makes what Rainer called "heroic simplifications." In the model, the scientists update their belief in part due to a herd response: they conform their beliefs to those of other scientists who have beliefs similar to their own. There are also some truth seekers who have a sense of where the truth may lie. They incorporate that sense as well in their updating of beliefs. Even a simple model like this gives the simulator many parameters to tweak. We were soon thrown into the details of the various simulations. There were lots of lovely charts, the hallmark of this field. In this case, they showed how beliefs of the unit scientists evolve over time. Even a small amount of effective truth seeking, it turned out, could drive the community as a whole towards the truth. Analyses of this type open exciting new vistas, for we are now able to grasp how a community's overall behavior may be much richer than that of any of its members. And, along the way, we get to play with some lovely computer simulations. We can churn out graphs and charts that display convergences, divergences and more. After a while, however, it became quite noticeable that no real example of a scientific community entered the analysis and there was no report of the beautiful results of the charts being tested against what really happens in scientific communities. Isn't that sort of checking essential if the simulations are to be more than speculative fun with one's latest simulation toy? Shouldn't we do that checking at every stage of the process lest we wander far from anything really happening in the scientific community?

Where might we get the data against which the models could be checked? That is a hard problem. But there is a lot of data to be had. Networks of literature citation are readily accessible via the internet. What about the NSF and NIH? They process huge numbers of grant applications and track the self-reported success of each of their investigators. They must have electronic drawers full of data.

The conference proceeded beyond these first three talks. However the shape of the field had already become clearer to me. It can be said as follows.

There is a model I keep in the back of my head for a good conference. It identifies scholars who need to talk to one another but they have not. This conference fits the model. Each scholar is addressing the same problem or some aspect of it; each can provide ideas, skills and methods to others; and each can profit from the ideas, skills and methods of the others. We have put them all in a room for a few days and encouraged them to listen and engage.

Who can say now what will come of it. However I can say that Kyle's instincts were spot on. This is a conference that needed to happen. And I think it should probably happen again. John D. Norton

|