![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

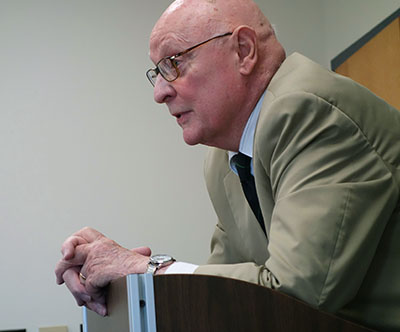

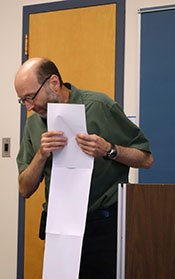

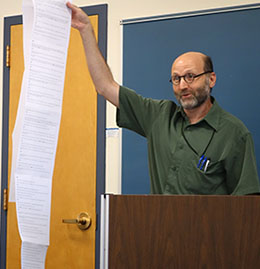

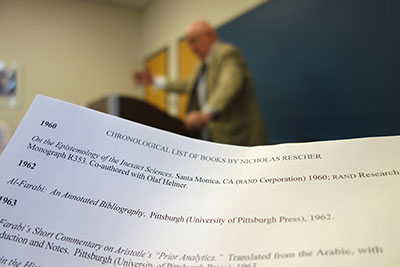

Introducing.... It is our first lunchtime talk of the year. May I relate a lighter moment? By tradition, Nicholas Rescher gives the first talk. It is designed, he explained with admirable modesty, to embolden us all. For after the coming catastrophe, he promised us, there is nowhere for later speakers to go but up! It is an excess of modesty, for Nick is a most accomplished scholar and speaker. To introduce him presents a special problem. How can one do justice to someone who earned his PhD from Princeton at age 21, a record then for the Princeton Department? That was in 1951 and he has been in continuous scholarly production since. So, I announced, after a few quiet necessities, that I would keep things short by merely reading the titles of the books he'd written. "1960--On the Epistemology of the Inexact Sciences," I began. At this moment, those who know Nick's prodigious publication list would have to be wondering what I was doing. The list is far too long to read out. I began to stumble over my words and then relaxed my grip. A long streamer of paper tumbled to the floor and piled up at my feet. I had taped Nick's publication list together into one enormously long banner. The cat was out of the bag and I handed over to Nick.

I had something in my back pocket just in case someone remembered that I had used the same device several years ago. "Didn't you already do that," I imagined someone calling out. I was ready: "Yes but now the list is longer so it is funnier." But no one remembered and this last riposte remained unused in my back pocket.

----oOo---- Nick's talk, "How Physics Works," was about the limitations on theories from our need to use observational technologies adapted to humans. Nick's goal was to lead us to some quite extravagant thoughts. But he would do it gently, in small steps. He began with quiet remarks on how our observational technologies limit us. We can only easily investigate nearby realms of modest temperatures and pressures. Then we find ways to enter realms with parameters orders of magnitude different. There we find new phenomena that cannot easily be accommodated by our older theories. Nick developed these ideas with more adventurous examples until he was contemplating how the specifics of our human structure inform the sort of theories that we produce. The thought is not so new, he told us: William James had speculated on the science that may come from lobsters and bees. Nick now wondered if jellyfish might ever produce metrical geometry with its rigid rods, rather than something more topological. Or can we expect digital thinking from beings without digits? Will moles, living forever in the dark, develop optics? Or might porpoises never develop crystallography but, instead, a very well developed hydrodynamics? I marveled at how Nick had brought us in an apparently seamless progression to imagining a porpoise genius in hydrodynamics. All this was done the old-fashioned way. There were no overheads or digital images. He was reading from his manuscript, as philosophers have done for hundreds of years. However, unlike so many who read today, Nick reads well. You see him read, but you feel that he is speaking with you in engaging conversation. Nick pressed on. He was no skeptic. There is one universe, one Nature and it has one set of laws. But how we see them depends on how we detect them. Where are the aliens who we routinely suppose are busily pursuing science in some far off cosmic corner? Where is their Encyclopedia Galactica that the science fiction writers imagine them beaming down to us? Might it be that we are busy listening for radio signals, but their science cares nothing for radio and is busy pursuing another channel of which we are quite ignorant? With that question, I shall stop. My exposition lacks the clarity and eloquence of Nick's words. After he had finished, we took our usual short break before question time. We chatted for a few moments at the podium as coffee cups were refilled and donuts and bagels tracked to their hiding places. It is, Nick then lamented to me, curious that no one in philosophy looks at these questions any more. A paper of this type would have a hard time passing through the filters of professional philosophy of science. His lament is quite right. The basic question of the uniqueness of our science and its dependence on our technologies is no less important foundationaly than it was in James's time. It may scarcely admit a definitive solution and it may even be hard to find a tractable starting point. Yet is not that just the sort of problem that requires careful philosophical analysis? It is best not entirely left to the undisciplined imaginings of science fiction writers. The neglect is, we agreed, a reflection on how our community has developed. We now mostly speak to each other about some small wrinkle in a recent turn in the latest debate over some issue that has been drawing attention for a reason we can no longer remember, let alone justify. I found the freedom of his thinking liberating. I am willing to entertain the radical thought that our science is unique and that it is pursued no where else in the universe in any form. The familiar rejoinder points to the selective advantage that science gives. The advantage is so strong, we are to suppose, that science must evolve in many places. Yet here on earth, we have over a million named species and many more without names. There is only one species that we can affirm has evolved science. John D. Norton (Thanks to Allan Walstad for photos of me.)

|