![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

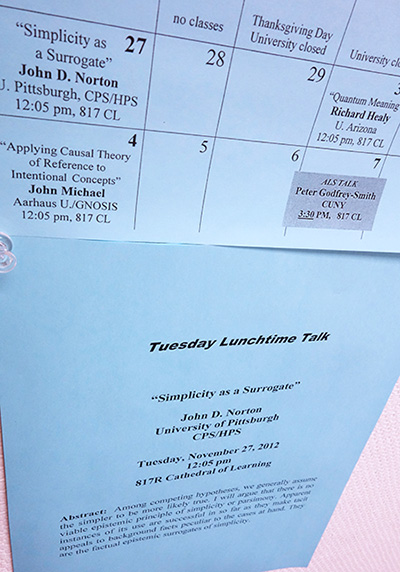

Simple "Simplicity as a Surrogate" "Do you still get nervous?" Serife asked me as we passed in the conference room. It was a little after ten in the morning. At noon, I was scheduled to give a talk. "Not really any more," I replied. "I've been giving talks for a long time. But I still worry. Do I have too much material for the time? Will I fit it all in?" Serife had caught me a little unawares. When I reflected more, I realized that I do get quite nervous still. A day ahead of the talk, I'm fiddling and fussing with minute details of what is already a perfectly fine Powerpoint. In odd moments, I find myself going over the content in the same way that tobogganers pre-visualize the course. That, I think, is healthy. My audience deserves the effort of proper preparation. Of course, it's no longer the stomach-churning terror that I felt decades ago. As I sat waiting for the room to fill and my talk to start, I found I really was nervous. What's the worst that can happen?

Well, realistically, what's the worst that can happen?

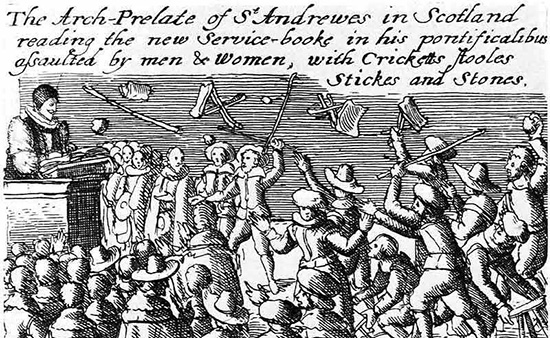

After it has happened a few times, it is less worrisome. Life does go on. As I sat with these reflections, an old philosophical friend wandered over to make the awkward sorts of remarks of encouragement that are common in these events: "I've been looking forward to your talk for a whole month," he said. Here I think I have his exact words: "So it better be good, else I'm not letting you out of the room alive!" I truly appreciated the sentiment behind the remarks, but I felt the delivery needed work. Kyle Stanford had agreed to run the show, taking my usual job. In the lunch room shortly before the talk, I suggested that he didn't need to give too long an introduction. His main task was to keep control of the proceedings. A vivid image sprang uninvited into my thoughts. "And if the room rises as a group to attack, your job is to throw yourself in front of them, crying, 'Nooooooo....take me instead!' " Kyle smiled. He's used to it now. Kyle began his introduction, which went on rather longer than I wanted. I took my last opportunity to take some photos of the room and of Kyle. He is a wonderful subject for a photographer. Since Kyle had offered to take over the job of photographer, I left him the camera as I went to the podium. My talk is about simplicity. It is part of the larger project of a material theory of induction. The central idea is that there are no universal inductive schemas or universal rules of inductive inference. In their place are facts. They provide the warrants for inductive inferences. I've been working through various candidate rules, showing in each case how the rules are really no rules at all, but merely an oblique reference to background facts. If we apply this idea to simplicity, used as an epistemic guide, we conclude that its invocation is really an oblique reference to some pertinent background facts that do the epistemic work. That is, simplicity is a surrogate, as the title of my talk proclaimed.

This idea is not so shocking. Once the project is sketched, it is almost a mechanical operation for a philosopher of science to work through the details. That was my sense as I proceeded through the discussion of curve fitting, tidal prediction and more.

However, in thinking about simplicity as an epistemic guide, I had ended up rereading Thomas Kuhn's seminal and celebrated 1973 lecture "Objectivity, Value Judgment, and Theory Choice." It was not a paper I'd ever much liked. This time, I found it especially irksome. Kuhn was going to explain in the paper why his view did not make theory choice "a matter of mob psychology." He talked of consistency, accuracy, simplicity, and more as criteria in theory choice. He could have deflected the charge of "mob psychology" merely by remarking how these criteria can be seen independently to guide us towards the truth. It's not hard to do. We know, all things equal, to avoid inconsistent theories, since they cannot be true. Yet Kuhn avoided such talk, in favor of labored discussion of the negotiations of scientists trying to trade off competing criteria. What bothered me the most, however, was a shift that happened half way through. The terms "characteristic" or "criterion" were replaced with "value." The notion of epistemic value thereby entered the literature and there it remains four decades later. It's just the wrong word. Criteria like simplicity function as a means to an end, finding the true theory. Their proper functioning as means has to be established by further analysis. Whether they function well is imposed on us by the world, not chosen by us. Values, at least as they are popularly understood, are ends that we value in their own right. They mark the end of analysis. When disagreement comes down to a difference of values, we have come to an endpoint very different from a factual disagreement that can be resolved by consulting a reliable source. In the popular understanding, values are chosen by a community. Different communities can legitimately choose different values.

If we treat epistemic criteria as values with these familiar connotations, we have subjugated theory choice to the whim of a social group in exactly the way Kuhn denied.

I laid all this out briefly, but, I think, clearly in my closing slides. I was expecting full well that this part of the talk would figure prominently in discussion. For some in the room, I was committing an obsessive, novice blunder. It would attract polite and nervous efforts to correct the impropriety and get the Real Truth out, while not embarrassing the speaker too much. And that is just what happened. John D. Norton

|