![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

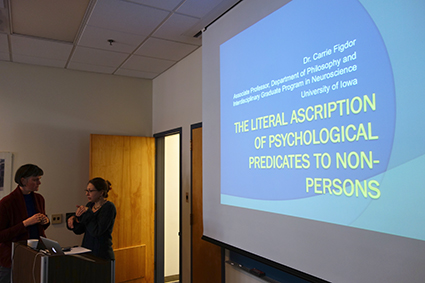

Neurons prefer... Science began when we stopped explaining the seasons by the periodic grieving of the Earth-goddess and sought the material processes that necessitate summer and winter. Or so we HPS professors have assured our starting undergraduates for generations. While I have taken my turn in this ritual, I have done it only by suppressing the nagging worry that primitive peoples were just as smart as we moderns. Might they have understood their animism in a more sophisticated way? However oversimplified our characterization of these generic, primitive thinkers may be, what lingers is the default supposition that anthropomorphism in science is a beginner's mistake, unworthy of a serious philosopher. Carrie Figdor is a Visiting Fellow in the Center this year and I have been listening to and reading her work against the background of this lingering animus against anthropomorphism. She maintains that it is quite proper for us to apply overtly psychological terms to things that are not people. "Antibodies recognize antigens,"--literally--she had assured us when she spoke in a lunchtime talk last term. Today she is developing those same ideas further. "neurons really prefer..." "antibodies really recognize..." or, more completely, we are told in the primary neuroscience literature that: "Neurons that are resonators prefer inputs having frequencies that resonate with the frequency of subthreshold oscillations of the neuron." And that is literally so. In philosophy of science, you soon find that some have mastered the trick of the outrageous claim that draws attention. Thomas Kuhn assured us that "after Copernicus, astronomers lived in a different world." (Structure, pp.116-17) You also soon realize that it really is not worth the trouble of arguing why this is nonsense if read literally and banal if read metaphorically. That was my first reaction to "neurons prefer..." But Carrie is eloquent and persistent and I found myself slowly drifting towards agreement.

Compare "prefer" in "neurons prefer..." and “Capuchins prefer grapes to cucumber slices.” They are clearly not homonyms: words with different meanings that sound the same, like riverbank and Wall Street bank. Nor are they perfect synonyms with identical meanings. Neurons do not consciously prefer in the way I like to think that capuchins do, both monkeys and monks. The two uses are polysemous. That is, they have different but closely related meanings; and the context tells us which is applicable. A polished mirror "is flat" in a way that is different from how Nebraska "is flat." But the proximity in the meanings is close and clear; and the context tells us which is intended. No one praises a polished optical mirror for being as flat as Nebraska. It is the same when neurons and capuchins prefer. What else might one say? The real competition is that one is used metaphorically. Capuchins really prefer, but neurons only metaphorically prefer. That possibility became Carrie's target and she methodically chipped away at it until little remained. The argument that carried greatest weight with me pointed out the neuroscientists' use of the term. When you speak metaphorically, you usually give flags of that use and even have an obligation to provide them, lest you be misunderstood. But the neuroscientists provide no scare quotes or awkward "as it were's." They present the usage as literal with no concern in evidence that you might misunderstand them. The text has no warning wink, so to speak. As the talk developed and I was swept along with Carrie's arguments, I realized that my focus was moving to a different question. I'm willing to accept the literal use of "neurons prefer..." But that acceptance only comes with a sense of disquiet. What am I giving up? What presumption about the world am I overturning? What am I agreeing to that might come back to trouble me? My reflections had moved from disputation to diagnosis, and Carrie's talk followed. As the talk drew to a close, she pointed to what might be the source of discomfort. We resist allowing the literal use of "prefer" because of misplaced moral concerns. If we truly feel that our planet earth is alive, we take on new obligations towards it. When we apply psychological predicates to certain animals, we find it harder to mistreat them. The mistake is that we assume our moral categories will coincide with those in nature. We can say bean sprouts seek the light, without thereby making it immoral to eat them. That seemed a plausible diagnosis, but it did not entirely dispel the discomfort. To what have I just unwittingly agreed? Katie Tabb in question time had reminded us of the hard fought battles in Darwinian evolutionary theory in which talk of intensions and purposes were suppressed. Cats may grow whiskers in order to navigate better in the dark, but they did not plan to grow them for this purpose. Carrie, I must assume, has further uses for claims. Tomorrow, on Wednesday, our informal reading group will meet. We will discuss Carrie's paper. The dynamic will be different. No matter how hard one tries to break it down, there is an adversarial formality in question time after a talk. Differences can be delineated and doing so sharply and clearly is usually the best one hopes for. In the relaxed informality of our reading, new ideas and perspectives can emerge, or so I like to think. Last week, we baked some small apple strudels and filled the room with sweetness. This week, while the ice and slush lies thick outside, I plan a tropical theme: fresh pineapple and banana bread. John D. Norton

|