![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

|

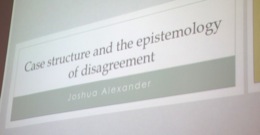

"...Or So He Says..."

Joshua Alexander

Lunchtime Talk

Oct. 10, 2014

Disagreement fuels philosophy. It compels us to refute opposing views and defend our own. It drives us to articulate our views more deeply and defend them better.

Disagreement also fuels acrimony. It gives us the awkward moment when a cordial conversation becomes tense. We each realize that a few casual remarks have unmasked a deep disagreement. We must decide whether to pass over it in momentary politeness or engage and perhaps mar a friendship.

Both these aspects of disagreement are everyday occurrences here at the Center. So it is with the greatest of interest that I learned that Josh's topic of research during his term in the Center would be disagreement. Today he is giving a talk on the subject.

I am interested, very interested, and my interest is both foundational and practical. I managed a contrived introduction that gestured at disagreement by appending "or so he says" to each item read from his CV. It got a little titter of laughter in the room the first time I said it. The floor is now his. Where will he take us?

We learn quickly that Josh's approach will be indirect. He is an experimental philosopher, so he is not inclined to address the philosophical questions directly. He prefers to study how people think about philosophical questions. The analysis will be one step removed. This will be important, it will turn out.

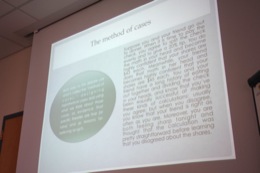

So how do philosophers think about disagreement? They do it by the method of cases. That is, they describe invented scenarios--"vignettes" as Josh calls them--and these lead the reader to the view intended.

An early case study is typical of the cottage industry that has grown up around the epistemology of disagreement.

It is a story in which you and a friend at dinner compute a 20% tip, but disagree on whether it is $43 or $45. The vignette is careful to arrange things so that there is no good reason for preferring your own to your friend's computation. You are both equally reliable at arithmetic and you both feel sharp.

While this was being explained, I was watching Josh's evident comfort as a speaker. Some retreat and remain behind the protective rampart of the lectern. Others move a little more freely. Josh, however, seemed so eager to project his ideas into the room that he projected himself. As he spoke he walked into the room, past those sitting near the front and then back again.

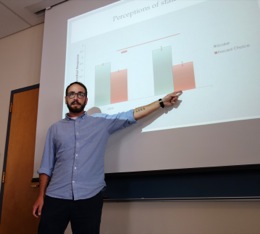

Josh's project is not to come to a decision on the two views. Rather it is to see how a community of thinkers comes to its views. That grew into a huge project in experimental philosophy. He and is co-workers culled some 20 vignettes out of the literature. They then presented them to some 2,000 subjects and queried them in all manner of ways.

They then dissected the responses according to many variables. Were the subjects asked the discrete question of which of the equal weight or steadfast views they endorsed? Or were they asked how their confidence had changed? How were their answers affected by whether the subjects themselves were in the vignette? By whether there was some objective way to decide? By the practical stakes? And so on.

The results were revealing. All these variables affected the results sensitively. Subjects were as likely as not to hold one view or the other, with changes in these variables flipping them from one side to the other.

One conclusion, Josh continued, seemed clear: philosophers can drive a subject to a particular view by artful scripting. "Philosophers," he said, "are good at getting what they want." He halted there, not wanting to be the negative experimental philosopher. The obvious and important continuation hovered silently in the air.

When question time began, I saw that there were a lot of questions. Good, I thought, there's a lot here to talk about. Seeing how many there were and fearing the worst, I made a plea: "Brevity!"

Then the questions began. It was a tame start. Josh was questioned on some detail of the experimental protocol. The exchange was quiet and not prolonged. Then came the next question on the protocol and more like it. We were getting through the list quite quickly, but no one was drawing attention to the central oddity of the whole business.

I began to prepare myself for a question that was really an excuse for one of those long speeches. Soon it was my turn to ask. I don't have my speech recorded verbatim. I said something like this:

"My question is not about your experimental work. That is quite wonderful. My question is about why this literature on the epistemology of disagreement exists at all. How could it be of any philosophical importance when two people disagree on what is 20% of $225? That is arithmetic and one or more of them have made a mistake."

"Well," I continued, "the scenario in which something like this could matter is when we think that rationality itself has a social component. That happens. I accept a vast amount of science. It is not because I have checked every experiment and reworked all the derivations myself. I trust the textbooks. I trust the scientists who report what they have done."

It makes sense to ponder disagreement in that scenario. Do we follow the scientists who report anthropogenic climate change; or those who dispute it? There are many interesting, philosophical issues when experts disagree. They key thing in all of them will be to investigate further to find some asymmetry between the two experts. Perhaps one is using evidence selectively; or one has made a subtle error in statistical analysis; and so on. Or, if we take the social element seriously, we might investigate the track record of each expert or even their funding sources.

Within this scenario, there is a circumstance of least interest. That is the highly contrived circumstance of two experts, equally matched in every conceivable way, but still disagreeing. For then there's nothing to be said. If they are perfectly matched, if there is a perfect symmetry, either they must come to the same conclusion, if the methods are powerful enough to give one; or to none at all, if they are not so powerful.

If we are now forced to imagine that they disagree, the only conclusion we can come to is that one or both have made a mistake. By its contrivance, the scenario gives us no clue as to what that mistake is. Worse, the supposition of perfect symmetry suggests that there is none. There's nothing more that subjects interrogated for a response can say. Pressing them endlessly to deliver something more will surely lead to meaningless vacillations as the subjects search for some tiny clue as to how the symmetry might secretly be broken. They will be like dry leaves that blow whichever way the breeze momentarily points.

Or at least that is how reasonable subjects should behave.

Do they? Josh's results showed exactly that. Make slight changes in the questions asked. Make slight changes in the scripting of the vignettes. They are nothing more than slight changes in the breezes; and the subject will follow them.

As this speech unfolded, Josh was watching me with an embarrassed smile. He must have heard this before, I thought. But I'll finish.

Josh's answer was non-committal. He could see why I thought what I thought. By this time, I had a head of steam and was not going to stop:

"You have a resounding case. You can blow the whistle on this pointless literature. Why not do it?!"

The answer came with a weary sigh. Experimental philosophy has a reputation for being negative. It needs to get away from that.

John D. Norton