::: center home >> news >> grünbaum |

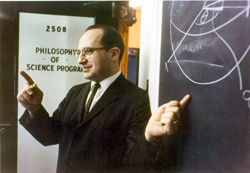

| Adolf Grünbaum

The most decisive influence on the direction of my work during the first twenty-five years after receiving my doctorate came from Hans Recihenbach, Hempel’s own graduate teacher at the University of Berlin. While I was still a graduate student, Robert S. Cohen, who was a serendipitous bibliophile, brought me an out-of-print copy of Hans Reichenbach’s classic 1928 German work on space-time philosophy, titled Philosophie der Raum-Zeit-Lehre. This book did not become available in English translation until 1958 under the title of Philosophy of Time and Space. When I read it in German, its effect on me was truly electrifying, and I was swept into working on the sort of issues that Reichenbach had treated so magisterially in that book. Years later, I developed a cordial professional and personal friendship of long duration with his widow, Maria Reichenbach, who was an indefatigable translator of his German writings into English. Thus, in 1963 I published my book Philosophical Problems of Space and Time (PPST), under A.A. Knopf and dedicated it to my wife, Thelma. This first edition was followed a decade later in 1973, by a second, a treatise of about 885, nearly twice the size of the first. This new edition appeared as volume 12 of the Boston Studies in Philosophy of Science coedited by Robert S. Cohen and Marx Wartofsky. In a review of this second edition in the Journal of Philosophy, Lawrence Sklar, a well-recognized author in the field, declared:

---------- [Provost] Peake and I likewise saw eye to eye on the creation of a Center for Philosophy of Science (initially labeled a “Program”), modeled on the pioneering Minnesota Center for Philosophy of Science at which I had held visiting appointments. I was to be the founder and first director of Pitt’s Center. Our fledgling Center would offer an Annual Lecture Series by prominent philosophers of science from universities in the United States and abroad, a series which I would organize each year. My hope then was that the papers in each series would merit publication in book form, an aspiration that was then realized. |

Adolf Grünbaum has drawn our our attention to his recent autobiography:

Adolf Grünbaum has drawn our our attention to his recent autobiography: