![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

Risk Conference This past year was the Center's Year of Risk. To be more specific, a grant from the Harvey and Leslie Wagner Foundation made it possible for us to invite an expert in the philosophy of risk to work for the year in the Center. He would then run a philosophy of risk conference at the end of the year. That expert is Nils-Eric Sahlin of Lund University. Since last September he has been a prominent member of our Center community. He has been a most welcome presence. He has a beaming smile and an extraordinary power to identify the good and lovely in everything he meets. When he first arrived, we sat in idle chatter. The environment of any place, we agreed, is very important for whether it can foster creative work. "That was the first thing I noticed when I walked in the door," he told me. "I heard laughter. I knew this is a good place." It was both blatant flattery and a childishly simple truth. The combination made it irresistible and completely disarming. There are many parts to Nils-Eric. This cheeriness masks a second Nils-Eric whose face will darken with passion over injustices in the world or when the moment comes to tell us that there is, without any possibility of error, a quite definite solution to the problem we may be discussing.

However Nils-Eric persisted. Ramsey would pop up again and again. Eventually, he had our reading group pore through a hefty synopsis and appreciation he'd written of Ramsey's work. I had to admit he was right. Ramsey by age 26 had achieved more than most of our number could achieve in several lifetimes. Somehow Nils-Eric manages to combine all this into one body. His smile will broaden and his eyes will twinkle and out will come something utterly outrageous. But it is delivered with such warmth and good humor that you want him to be right, even when everything else speaks against it. These exchanges became a favorite part of my day. Nils-Eric starts the day early and he is usually in his office, sprawled over his chair and desk when I arrive. I pop my head in to say "hi" and I never quite know what happens next. Earlier last week it was hunting wolves. He had been invited to an interview on the topic by Swedish radio. What could he say? In the course of the day, I found out. As we passed in the hall, I learned a that no humans had been killed by wolves in over a hundred years in Sweden. The lethal menace to wolf hunters was other wolf hunters who routinely succeeded in doing what wolves had long abandoned. What worried the hunters most proved to be the attacks by besieged wolves on the hunters' dogs. Nils-Eric was developing opinions that, he feared, would lead him to exile from Sweden should he announce them on the radio. The next day, it was a different danger, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland. Would the new, higher energy experiments create miniblack holes that would destroy the world, as some lawsuit against them had proposed? Would this be a good risk case study? A little later, a follow-up email linked to a website at CERN and assured me that I would survive to lunchtime and later.

As all this unfolded, Nils-Eric was working hard on his conference. It would be no ordinary conference. The topic of risk cuts across many fields and many would be represented. We would hear from the philosophers who work on decision theory; from psychologists who think about how we think about risk; from statisticians who count and weigh the risk; and from philosophers who try to use their insights. When the day finally came, we were a little on edge. There had been a series of hoax bomb threats in the Cathedral over the preceding weeks. They were tiresome affairs. A siren sounds. A voice comes over the PA system. We dutifully file down the stairs and out. Some two hours later, when the all-clear is sounded, we return, muttering about some d*mn undergraduate trying to get out of a midterm. We had gotten sufficiently rattled by the surprise evacuations that, at the last moment, Karen and Nils-Eric had managed to arrange a backup room elsewhere. We hoped it wouldn't be needed. Shortly after 10am on the morning of the conference, the siren sounded. Fortunately there was time enough for the campus police to check the building, again. We were safely back in our offices by the conference start time of 1pm, wondering just what might happen next. I thought this exposure to a hoax peril provided an interesting backdrop for a conference on risk. It proved to be a conference of extremes. This became clear at the outset through the stark contrast of the first two talks.

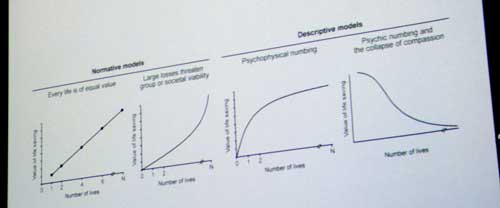

Our natural default, Paul explained to us, would be to assign a simple linear relationship between the value and the number of lives. Twice as many lives should be twice as valuable. Of course that is not what the psychologists find when they investigate how people actually value life. We find all sorts of failures. On the one side, there is "singularity." We value a life much more if we have specifics about it. It is the Mother Teresa effect. A photo of Mother Teresa caressing an emaciated baby flashed across the screen. On the other side, there is "numbing." As the number of lives grows, the value we assign slows. As we pass the thousand count, we no not value the next starving child as much as the first. One might be inclined to dismiss all this as a few anomalous cases. But the depressing examples kept coming. We happily spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to save a stranded animal, because it has a name and face in the media. A somewhat minor case bothered me. Do we spend $300,000 to treat just one sick child? Or do we spend $300,000 to treat eight sick children? When donations were sought, they poured in for the first option, over one that seemed eight times more worthy. Or are we thinking that the first option is more needy and its support more virtuous, since we judge, erroneously, that others are less likely to support it? Nils-Eric had scheduled the conference tightly. 30 minutes speaking time; 15 minutes discussion; and then onto the next. I like the pace. Speakers have to come to the point sooner. But it did mean that there were no seconds to lose. We had started exactly on time with the room pretty much full. Our larger audience had not sensed the pressure of time. Over the ensuing 10 to 20 minutes a steady stream of late-comers arrived, filling the room and the entry hall. I watched their heads bob about, seeking a glimpse of an empty seat. Then they would compute whether taking it was worth the ignominy of disrupting the speaker. When Paul's talk was over, I felt deflated. It was not just that our communal assessments of human life seemed so unkind. I had long known from chance encounters with psychology that rationality comes only painfully to us. It was that there seemed to be no intelligible rhyme or reason to how these values were being assigned. Sometimes question time can clear the fog. John Lyne asked the question. Is there some evolutionary advantage to the way we assign these values. Of course--what was I thinking?! We'd developed assessments of values that were well adapted to the situation of our forebears in some distant primitive past. Paul extended the point quite well. That may be so, but we no longer live in the distant past. We do have to recalibrate ourselves.

Her focus was the requirement of expected utility. Loosely, it tells us to choose that which gives us the best on average. Should we prefer an assured $1 to a 50% chance of $3? The expected utility of the second is higher. It is 0.5x$3 = $1.50. Choose outcomes like this and, in the long run, we come out better. Here's another choice. Do we prefer an assured $1,000,000 or a 50% chance of $3,000,000? Once again, maximizing expected utility tells us to choose the second. But I'd take the sure million over the chance for more and run. And I'm guessing that you would too. Is this a breakdown of decision theory? No, Lara assures us, we just need to adjust the decision theory to accommodate what is actually a quite rational aversion to risk when the stakes are high. The adjustment proves to be a simple change in the formula for expected utility. We add weights to the formula reflecting the differential risk that separates the two cases just described. Decision theory is a theory. It is more that just a rule that tells you which option to pick. The theory that now concerned Lara is an axiomatic version set out rather like Euclid's famous geometry. One writes down simple conditions to which everyone must assent. If this choice is alway better than a second, choose the first. The mathematical rollers mesh and turn and out comes the expected utility rule, neatly pressed and ready to wear. Could these axioms be adjusted to accommodate the new rule? It could be done and Lara turned to the complexities of showing us. She drew some figures on the blackboard and pointed us to parts of the four page hand out. The 6 axioms of "Expected Utility Theory" were now replaced by 7 analogous axioms of "Risk-Weighted Expected Utility Theory."

This last part has long seemed dubious to me for it has become clear to me that other decision theories are possible. The axioms entail the theory. Hence they are at least as strong logically. So if other theories are possible the axioms must harbor less than innocent assumptions that fail somewhere. Lara was now inadvertently going through the exercise of making this point. She had found an alternative decision rule and was working back to show how the self-evident axioms were to be replaced by other self-evident axioms to form a new decision theory. I had little doubt the exercise could be repeated for other rules. The axioms are only self-evident until they are not. Now it is question time. Paul Slovic raises his hand to ask a question. I was reminded of the stark difference between the caveman eccentricities of Paul's talk and the Euclidean computations of Lara's. One had found irrationality in the one place where it is most important to be rational, our assessments of the value of life. The other found mathematically precise rationality even when it seemed that irrationality prevailed. Paul addressed one part of their difference: Lara's decision theory is a universal theory that works everywhere. But Paul had found things otherwise. "Context is everything" he said. "Preferences are squishy." This was the moment that the two extremes met. There could be no simple accommodation, I thought. They would simply need to acknowledge that each was looking at a different part of the animal. The best for which we could hope was that it would prove to be the same animal, so that eventually they would see the same beast if they could each widen their gaze. Lara said the only thing she could. Philosophers are interested in ideal rationality and ideally rational agents. Its subject is not how our caveman brains decide, but how they should decide. Connecting that to real human behavior remains an unsolved problem.

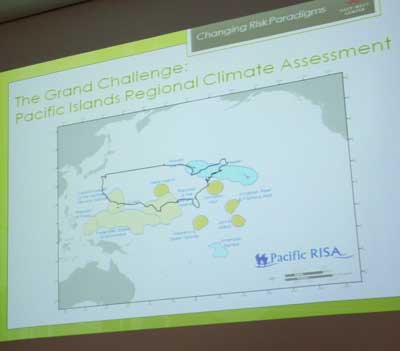

We broke for coffee. As we slowly drifted back into the seminar room for the next talk, real-world risk reappeared. The sirens sounded. All conversation stopped and we stood quietly looking at each other. "Do we evacuate?" someone asked. I was thinking quickly; and my thinking was that we should not act too quickly. Not all the pieces were there. "I suggest we wait," I called out. "What usually happens is that a loud voice tells us to leave and we get alerts on our cell phones." I held my silent phone aloft. Blank faces can be hard to read. Were they reassured? Or were they thinking about how sorry I'd be if this turns sour? Then the voice boomed. "This is a test. This is test of the emergency alert system." The conference continued through the remainder of the afternoon and for all of Saturday. Our range remained large. We had talks in traditional decision theory, in statistics, on the role of emotions in decision, on the practicalities of implementing regulations and ecological management, on uncertainties in climate science and even accounts of risk from climate change in the Pacific Islands. The shape of the field was becoming clearer to me. The talks were mapping a space by identifying three boundaries. One was the mathematical theories of decision by ideal reasoners. Another was the study of how we much-less-than-ideal reasoners actually make decisions. The third was the risky situations in which decisions are to be made. These boundaries were becoming clearer. But the space in the middle where all three would meet productively was remaining uncomfortably vacant. Through all this, Nils-Eric had positioned himself quietly towards the back of the room. He was the mischievous imp who had lured the other children into a brawl and was now enjoying the spectacle. I wondered how long he could keep himself hidden. He had once or twice asked questions that were just a little provocative. How many of us have berated Jay Kadane for making a "typical Bayesian mistake"? Or accused Teddy Seidenfeld of "impersonating a classical statistician"? It could not last. He has a head full of outrageous thoughts, and he knows that they are outrageous, and he knows that they are right. So sometimes they must be said.

"I cannot resist," Nils-Eric called out from the back of the room, "I will make the psychologists upset now." What followed was a pointed denunciation of "dual process theory"-- the theory that separates a fast emotional component and slow rational component in our thinking. Sabine was smiling since this speech was quite entertaining. "We are not defending the theory," she finally interjected, "We criticize it." Nils-Eric had more, and I continued to write down his words as he spoke. "Put more emotions into decision making?! That would be a catastrophe. Keep the emotions out." And then came the closing insight. I should have seen it coming. "What we need is to put more Ramsey into decision theory!" This was not the last moment of the conference. But it was one that was not to be bettered. When our time was over. Nils-Eric stood to make a brief speech of thanks. Harvey Wagner, the Harvey Wagner of the Harvey and Leslie Wagner Foundation, had made the trip and was present for many of the talks. He had asked that we not make any speeches for him. But Nils-Eric felt that would not be right. He told me later that his dead mother would return to earth to berate him if he did not do it. So he spoke a few words of thanks to Harvey and then called on me; and I did the same. It was not what Harvey had requested, but for once I felt that we did the right thing in not doing what we were told. John D. Norton |

That leads to the deeper passion. It is Frank Ramsey, the Cambridge philosopher and mathematician who died at 26 having made foundational contributions to philosophy, decision theory, mathematics, and more. He would convert us to Ramsey, Nils-Eric assured us. I smiled at this boast. It is not the first time I have heard such speeches. I've had the benefit of many of them in my time, and I have become especially impervious to enthusiasms.

That leads to the deeper passion. It is Frank Ramsey, the Cambridge philosopher and mathematician who died at 26 having made foundational contributions to philosophy, decision theory, mathematics, and more. He would convert us to Ramsey, Nils-Eric assured us. I smiled at this boast. It is not the first time I have heard such speeches. I've had the benefit of many of them in my time, and I have become especially impervious to enthusiasms.