Exploring Physical Chemistry with Mobile Devices

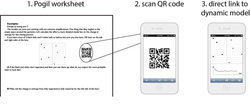

Guided inquiry methods, POGIL for example, are an effective way to introduce active learning to the science classroom. Students begin by exploring a model, construct the explanation, and then learn the standard terminology for that concept. Because students construct their own understanding first, and then learn to relate it to overarching themes, these methods have shown marked improvements in student outcomes in both introductory and advanced chemistry classrooms. Typical guided inquiry materials are worksheets, which are effective in many cases. The subject matter in physical chemistry, however, often involves inherently dynamic processes and sometimes extended pen and paper calculation to flesh out a guided inquiry model. Computer simulations integrated into guided inquiry materials could radically change the way students engage with the toughest concepts in physical chemistry. These will be ‘numerical experiments’ packaged in a guided inquiry format for my Physical Chemistry courses at the undergraduate (∼35 students) and graduate (∼15 students) levels. Electronic course materials (HTML5 applications) are being developed which will marry monte carlo, molecular dynamics, and other statistical simulations to a guided inquiry format. This project provides the following advantages for students: 1) active learning for topics difficult to visualize on the static flatland of a peice of paper; 2) materials that are broadly accessible inside and outside the classroom; 3) students get an introduction to the foundational concepts of modern theoretical chemistry (computer simulation) earlier in their chemistry careers.

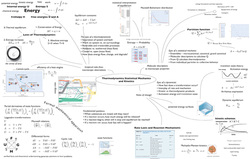

Course Roadmaps

I supplement the syllabus of my courses with a course roadmap — a visual summary which introduces the content, structure, and goals of the course graphically by displaying how the topics of the course fit together. This teaching tool has been useful to me and to my students, so I would like to share how I use it, how it affects student learning, why I value it, the guiding principles for developing these instruments, and some tips on the practical issues of producing them... (read more)

|

Related Material |