![]()

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

::: center home >> being here >> last donut? >> 29 September 2006 |

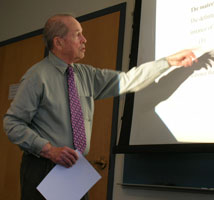

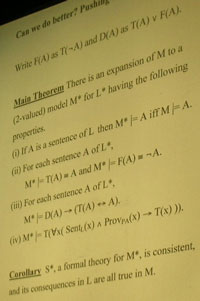

Friday, 29 September 2006 The speaker for our Annual Lecture Series is the distinguished logician, Sol Feferman. There is a quiet buzz of lazy conversation in the room, as those who came early to stake out the good seats watch the gaps fill with newcomers. The time passes. Now it is 3:30, our starting time, and there is no one at the lectern. The Center staff already knew something was amiss. They'd been passing between the offices looking for reassuring news that perhaps someone else had heard. Then Jim Tabery picked up a phone message and Joyce managed finally to reach our speaker at his hotel room. They had been in bad traffic and he would be arriving shortly. "Ten minutes"-- international code for "I don't know; I'll do my best." Anil Gupta, who would be the master of ceremonies, made a brief statement and no one seemed especially bothered. I'm relieved. It is every organizer's fear: you hold an event and everyone shows up except the speaker! I settled down in my seat, strategically chosen to give me the best line for photos, and waited. There was no sign of impatience in room. That, I mused, is what happens when you are really famous. People will wait. Someone sped in and slumped in a chair behind me, mumbling gratefully, "lucky for me they're running late!" 3:47 and a distinguished gentleman walked into the room. "That's Feferman?" I asked Mark Wilson sitting next to me. Somehow I'd expected trumpets and elephants to herald his arrival. But here he was. Anil's introduction was elegant and welcoming and the talk began. I wasn't sure what to expect. When news of his visit reached our colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University, they managed to convince him to give a talk there as well the day before, on Thursday. The abstract for the talk had arrived daily, like a steady rain, in my email inbox. It spoke of many wonderful things, that "the permutation invariant operations on any given domain were ... characterized by Vann McGee as exactly those definable in the language L_{\infty, \infty} allowing disjunctions, conjunctions and quantifier strings of arbitrary cardinality..." Alas I belong to that larger subset of humanity for whom L_{\infty, \infty} does not ever drift into everyday chatter. How much would I understand of the present talk? Familiar themes began to develop. Before you have that first undergraduate class, you imagine that a great philosopher talking about Truth must be something akin to a secular Pope revealing the deepest mysteries. It's nothing like that. It's just ordinary, everyday truth, as in, "it's true that this car gets 25 miles to the gallon." One scarcely imagines that idea could consume an hour's lecture, let alone many lifetimes of scholarship. We owe to the great logician Alfred Tarski what seems to be the obvious, 30 second explanation of truth. To use his celebrated example, the sentence, "Snow is white." is true, just if snow is white. All this seems perfectly obvious. What's the fuss? Well, it all falls apart the moment you have sentences that themselves talk about truth and falsity. You just cannot do that without getting into a mess. Take the "Liar." The sentence "This sentence is false." is true, just in case it is false. So it cannot be true or false. How on earth do we apply the notion of truth or falsity to it? Easy, you say. Just dispense with that sentence as neither true nor false. It is meaningless. But then what do you do with "This sentence is meaningless or false." If it is meaningless, it is true; but if it is true, it cannot be meaningless. These sound like children's tricks. A cat has three tails since no cat has two tails and one cat has one more tail than no cat. But they cannot be made to go away like these riddles just by speaking a little more carefully. There is no easy escape. The problems are grave and remain unresolved today. They are the first page of volumes of ingenious scholarship. It is soothing to have a real master guide you over these familiar problems. Feferman reviews Tarski's solution: a type theory of truth in which there are different types of truth. There is the truth of sentences that say snow is white; and the truth of sentences that talk about these sentences; and further sentences that talk about them; and so on. All these are different types of truths. As the history of the problem unfolds, the technical apparatus becomes subtly more complicated. I know that it is only a matter time before I am out of my depth. So I start to let go, simply taking pleasure in the thought that I am hearing of the work of the great Tarski from a great logician who was himself a doctoral student of Tarski in the 1950s. I'm thinking degrees of separation. Some 50 minutes into the talk. Feferman checks the time with the chair and announces that finally he has arrived at the novelty. Feferman is not happy with a theory of truth that has infinitely many types. Truth just should be truth. He lays out his own untyped theory of truth. The talk is no longer a review of familiar material. Anil interrupts the speaker once or twice to ask why both this and that are assumed; or whether this applies there. The second question stops Feferman and he stands for long moments gripping his chin, thinking. The talk ends one hour and fifteen minutes after it started. That is longer than most, but no one seems to mind. We break for wine, cheese, soda and chips. The Annual Lecture Series in our name event and we try to remind everyone of the dignity of the occasion with more dignified fare. No donuts. We are finally settled down for question time. "Questions!" Anil commands. There is silence. I'm thinking, "After that virtuoso performance, I'm not asking a foolish question!" As the silence lengthens, I begin to realize that this is the thought on everyone's mind. What can we do? I sit and wait; and everyone sits and waits, through the longest silence I can recall in a public talk. The silence is finally broken by Nuel Belnap, himself an eminent logician, and the question time begins. John D. Norton Solomon Feferman

|