::: center home >> being here >> last donut? >> variations |

20 January 2009 Our speaker today, Federica Russo, has been thinking about causation for many years. The concern dates back to her Bachelor's studies in Padova and through to her doctoral dissertation in Louvain in Belgium. The continuity to this moment is strong. Her dissertation was entitled "Measuring Variations" and the very same title is now displayed on the screen at the front of our seminar room, as Federica begins her lunchtime talk. She is clear from the outset as to where her talk will take us. Over the last few decades, there has been an explosion of interest in the topic of causation in philosophy of science. Each scholar who approaches it finds a new way to understand its complexities and to vary the common themes that unify our thinking on causation. "Variation," she warns us conspiratorially, is the "take home message." What she proceeds to unfold is a single, sustained argument for the centrality of the notion of variation in the epistemology of causation. Many have thought long and hard about causation, including those sitting in this room. When we, as speakers, have an audience like this, we have learned that it can be hard to convey our novel perspective. Our audience is not merely listening. It is listening and comparing what we say with what they already believe. When the divergences appear, they listen less and begin to formulate their questions. What can an experienced speaker do in these circumstances? Just what Federica did. She prepared us by mapping out in some detail what the talk is NOT about. That just might refocus a few of us on her thoughts and away from our pet beliefs. Her analysis, she tells us, pertains only to social sciences in which there is quantitive analysis. She will not try to say what causation truly is. That is a reef on which many noble ships have foundered. Her concern is only the epistemology of causation. What is the rationale that guides us in our causal reasoning, she wants to know.

The analysis continued in this vein, through Suppes' old portrayal of causation as probabilistic dependence to Woodward's more recent interventionist account and then on to the history. If we look in the nineteenth century heroes of statistical-causal analysis, Quetelet, Mill, Durkheim, the repeated and essential theme is variation. That was the main argument. Now came the rejoinders to objections as yet unvoiced. What about regularity? What about invariance? Aren't they more basic? No--one needs variation before one can talk of regularity or invariance. It precedes them conceptually. Now it was time to wind up. Federica pointed to the practical benefit in causal investigation in a focus on variation. If we seek the causes of unemployment, say, we should look at what accompanies the varying of candidate causes. What happens if we change the education level of our subjects? Or track their fates over time?

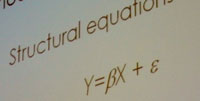

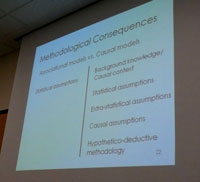

In the causal models, one secures the causal character by adding a list of additional ideas that supplements the pure statistics. The list includes background assumptions, additional statistical assumptions and even causal assumptions. She meant, I supposed, that we judge that maternal education causally affects child survival and not vice versa, because the education precedes the child. The causal assumption informing that judgment is that causes precede their effects in this domain. We broke for a few moments to attend to the remaining bagels and donuts. These last items, however, had become a matter of some controversy. Peter Machamer had already complained to me about the transition to the new, more colorful donuts that was already mentioned here before. Since I rather liked the decorative effect of our new and more imaginative donut chef, I had put the question to the room at the start of the talk. I could find no one who approved of the new colors. Anyone who had an opinion was unfavorable. This unhappiness, I said, would be passed on. Afterwards, perplexed, I carefully sampled a slice of each of the remaining donuts. There is no trace of the bright colors in the flavor. And then I found a quiet rebel faction in the Visiting Fellowship who approved of the new colors. The donuts were quickly forgotten as the room began the usual jockeying for first place in the list of questioners. As the questions came in, first from Sandy, then Peter and on beyond, it became clear that one thought would dominate discussion. Variation is good, but it isn't enough to distinguish causation. We had seen association and causation compared and both manifested variation. That couldn't be what made the difference. What ensued was one of those curious exchanges in which the speaker grants the point as one she herself believes, so you would expect no disagreement. Yet it continues. Half full! No, half empty! And then I saw a way that the glass could be turned on its side without spilling. I posed thought in a question to Federica. This is an audience that will heckle a questioner. And while all this unfolded, I could see that at least one of us had his head on matters of greater moment elsewhere. Coinciding with the talk, Barack Obama was being sworn in as President of the US. In our lounge just before the talk, Claus had told me he planned in the moments left to see a few pictures of the inauguration. Later, when he asked his question, Claus illustrated his query by remarking that "No causal influences come from Washington..." I could see what was still on his mind. John D. Norton Lunchtime Talk |