::: center home >> being here >> last donut? >> unsimple truths |

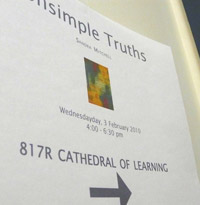

Unsimple Truths

Wednesday, 3 February 2010 The unsimple truth is that I don't remember when I first heard that my colleague and Chair of the Department of HPS, Sandra Mitchell, was writing a book on complexity and the philosophy of science. It was not to be an ordinary book. It would be a pocket-sized text aimed at a broad, popular audience. Well, it might not be quite so broad since its readers would need to be undaunted by terms like "integrative pluralism" and the "evolutionary contingency thesis."

In the months following, Sandy began to disappear into short excursions to Germany where she had been invited to speak in venues outside normal philosophical circles. As Sandy grew weary from the travel, we began to see in her absences that she had something of a hit on her hands.

In the workshop, we would hear from Jim Bogen and from Dale Jamieson, who'd made the trip in from NYU. Commenting, as they had agreed to do, is not easy. The event is clearly intended to have a celebratory tone. However philosophical discourse does not function well on agreement. Commentators are expected to find tensions somewhere, but not so many as to be insulting to the author. So it is always interesting as an illustration of the craft of philosophy to see just how a commentator balances the competing demands. Sandy 's volume is complex. While I knew many of the ideas in the volume from Sandy's talks and papers, I had read the volume hastily over the previous weekend in order to absorb it as a whole. It was clear to me that my whole might not be everyone else's whole. The basic theme of the book is that the complexity of the world needs to be accommodated into the way we conceptualize, investigate and act in the world. Under conceptualization, Sandy noted, we needed a new pluralist approach to theorizing that allows laws that do not have universal, exceptionless scope, admits many levels of explanation, that the choice of level be made pragmatically and that we recognize that our knowledge is dynamics and evolving. It was a good story and every good story needs a villain whose lingering menace is fought and overcome. That villain turns out to be a benighted reductive picture of science supposedly delivered by physics. This narrative is a commonplace amongst those who write on emergence in biology, but a frustration to people like me who work in philosophy of physics. In so far as there ever was a debate in biology worth having over reduction, it was settled ages ago in favor of reduction, when we decided that there is no animating life spirit. Living things are just big bags of wet chemicals. The only way to keep antireductionism alive is to try to saddle reductionists with dumb claims. Does anyone we take seriously defend the claim that the theory of cell biology should be replaced with the standard model of particle physics since cells are just many such particles? When it comes to theories, physicists are as integratively pluralist as biologists. Comets may be big messes of quantum particles, but no serious astrophysicist uses quantum field theory to predict the return of Halley's comet. On pragmatic grounds, they make the prediction from a theory at a different level, classical celestial mechanics. These were my thoughts and apprehensions as I sat down to hear Jim and Dale. What would theirs be? It did not go at all as I feared. We philosopher of physics were not the villains. Indeed we rated no mention at all. The focus rapidly turned to an ingenious reductive argument of Jaegwon Kim. Higher-level phenomena, such as certain life processes, are identical to lower-level ones, such as certain electrochemical ones. So any causal or explanatory powers of the higher-level, emergent phenomena, are fully carried by the lower-level ones, thereby rendering the higher-level phenomena causally and explanatorily inert.

This was a perfect, communal negotiation of the dual burden of commentators. Sandy was not the battered target, besieged on two fronts. In her reply, Sandy could position herself between the two commentators and mediate. No, she responded, in a verbally clever turn, it is physics versus physical. Kim's argument needs the lower level to be the level of physics theory, not merely the physical.

John D. Norton |