or

or

Image: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Beijing_traffic_jam.JPG

| HPS 0410 | Einstein for Everyone |

Back to main course page

John

D. Norton

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

Linked documents:

Einstein on Kant

More from Einstein on the

Conventionality of Geometry

|

In earlier chapters, I reviewed some of the ways that special

relativity has been judged to have a significance that extends

beyond its immediate physical content. This chapter (and new

chapters still in the planning stage) take up the same exercise

for general relativity. As before, the goal is to bring some philosophical rigor to the assessment of the various morals claimed. So the reader is urged to review the early sections of since they sketch the method to be used. I will also include a statement of my view. Those statements are not to be taken as text-book truths. They are merely illustrations of how one philosopher of science--me--has thought through the issues. |

See: Philosophical Significance of the Special

Theory of Relativity or What does it all mean? Skeptical Morals Morals About Theory and Evidence Morals About Time |

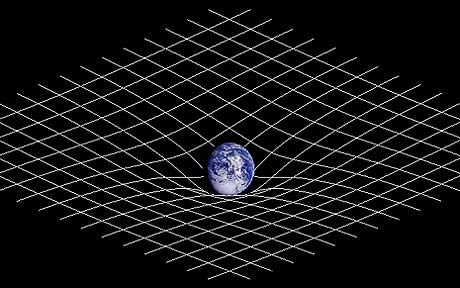

General relativity continued the assault on our older confidence in the certainty of the results of science. So some of the general described earlier can equally be traced to general relativity. We need not repeat them here. We need only add the observation that general relativity increased the sense of fragility of older science. It was not just that things behaved a little oddly when they moved very quickly, as special relativity showed. General relativity now revealed a failure of the basic ontology of Newtonian science, that is, of the list of entities fundamental to it. In Newtonian science, gravity is understood to be a force, where forces are one of the most basic existents in the Newtonian scheme. In general relativity, gravity is not longer a force. Rather the effects of gravity are associated with a curvature of spacetime.

The laws of geometry are not synthetic a priori truths.

In the decade following Einstein's completion of the general theory of relativity, one of the most important ramifications in philosophy was that it forced a reappraisal of the nature of geometrical knowledge. The work of nineteenth century mathematicians had shown that geometries other than Euclid's were logically possible. There was a sentiment growing among mathematicians that we should take these other geometries seriously as physical possibilities for the geometry of our space. For example, we shall see below that, prior to general relativity, Poincaré argued that the choice between Euclidean and other geometries as the physical geometry of space was conventional.

Einstein's discovery of general relativity forced the issue. It was no longer a matter of pure speculation that Euclid's geometry might fail somewhere, somehow, so that we would need a different geometry. Perhaps, it had been conjectured, Euclidean geometry might fail in the very large or in unusual circumstances, if our measuring rods were composed of exotic materials. Rather, Einstein showed us that our best theory of space, time and gravity had made the speculated failure a truth. His theory demanded that Euclidean geometry hold at best only as an approximation.

| The immediate casualty was one of the most

successful epistemologies of Einstein's era, that of Immanuel Kant.

The core novelty of that system was the idea of synthetic a priori

truths. A synthetic proposition is one says more of the subject than

is given in the subject's definition. An a priori proposition is one

that can be known prior to experience. Kant's epistemology was based

on the idea that there are truth that are both: synthetic a priori

truths.. The laws of geometry were a prominent, early example. Einstein now showed that these laws were not even truths, let alone known a priori. I have described the episode in more detail in earlier chapters, so the details need not be repeated here. For Einstein's view in his own words, see this. While Einstein's discovery considerably damaged the Kantian program, it continues to the present day in the revised form of various neo-Kantian traditions. |

See Euclidean Geometry: The First Great Science: Knowing with Certainty Non-Euclidean Geometry A Sample Construction: Einstein's Moral Spaces of Constant Curvature: Geometry is Empirical |

| I'm expressing my critical views concerning Kantianism in severe terms here. My intent is to correct a misapprehension that may arise when one first reads in philosophy and philosophy of science. One finds a vigorous literature pursuing Kantian themes. There is very little in the present literature that criticizes it. That does not mean that Kantian ideas have wide acceptance. The field has split. Those who find value in Kantian ideas continue to publish, but in what I believe is a minority, even if prolific. The larger community does not find the Kantian program interesting enough to pursue and even finds it opaque. The group says little or nothing about Kantianism, making its skepticism invisible. | Kantianism has been an epistemic failure from the start, especially as far as geometry is concerned. According to it, the most mundane facts of experience are not true of the world. Take the facts that the reader is, perhaps, sitting in a room, separated spatially from the rest of the world by walls, a floor and a ceiling; and, presumably, the Earth's South pole is spatially very much more distant than the walls. These spatial facts are geometric and, therefore, not a direct expressions of things in the themselves. Their spatial content is somehow invented by our apparatus of perception. If facts such as these are not really facts at all, then what do we know of the world? |

The situation is worse when we ask if we have saved science from Humean skepticism as Kant had intended. The concern was that Euclid had apparently found universal truths of geometry with a security that outstripped our meager epistemic means. Kant recovered the security. We are, he assured us, inventing these general truths through our perceptual apparatus. That is what forces the angles of a triangle to sum to two right angles. Hence we are assured that our experience will always deliver this result. However, in assuring us of that, we have given up the part that matters most. This basic truth of Euclidean geometry is no longer a truth about the things in themselves. The science is not saved. It is demoted to a fabrication, albeit an enduring one.

It is a mystery to me why we needed the advances of the 19th and 20th century to shake confidence in the Kantian picture. It is a greater mystery to me why modern neo-Kantians persist in efforts to save the program.

Perhaps the only salvageable residue is the idea that our conceptual systems provides a medium for conveying facts of the world and that we may have great trouble separating the facts of the world from the medium. That is an interesting if familiar idea. However we must never forget that the medium is not the message of facts of the world. If the regularities of experience we discover are merely regularities in the medium, we have not discovered truths about the world. All we have found are our own fabrications.

The metrical geometry of space is not given factually but is chosen by us as a convention.

While general relativity clearly demonstrated the failure of the Kantian a priori in geometry, there remained a lingering sense that something in the Kantian view was correct. We were somehow supplying something that was being mistaken for bare fact. The thesis of conventionality of geometry identified that something as the metrical geometry of space. It is that part of geometry that specifies distances between points, as will be explained in a greater detail below. The claim is that this geometry is not something that can be known factually, but is something we freely chose from many possible candidates. Where Kant had urged that we imposed Euclidean geometry on experience, the conventionalist now asserted that we freely chose that geometry from among many possibilities.

The sense of convention here is the same as the one we saw earlier in the thesis of the conventionality of simultaneity. As before the choice is quite akin to the decision in different countries over which side or the road is to be driven on by traffic. Some drive on the right; some on the left. There is no correct fact as to the proper side. Each country makes its own choice on the basis of convenience.

or

or

Image:

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Beijing_traffic_jam.JPG

Metrical geometry is that part of geometry that specifies the distances between points in the space. We can get a sense of how this is a part of the larger geometry by looking at a familiar example.

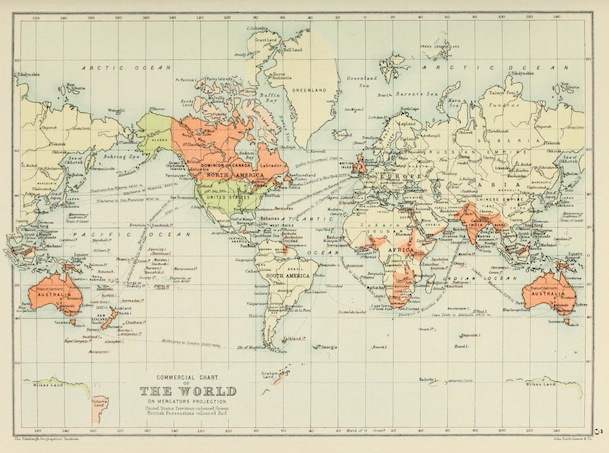

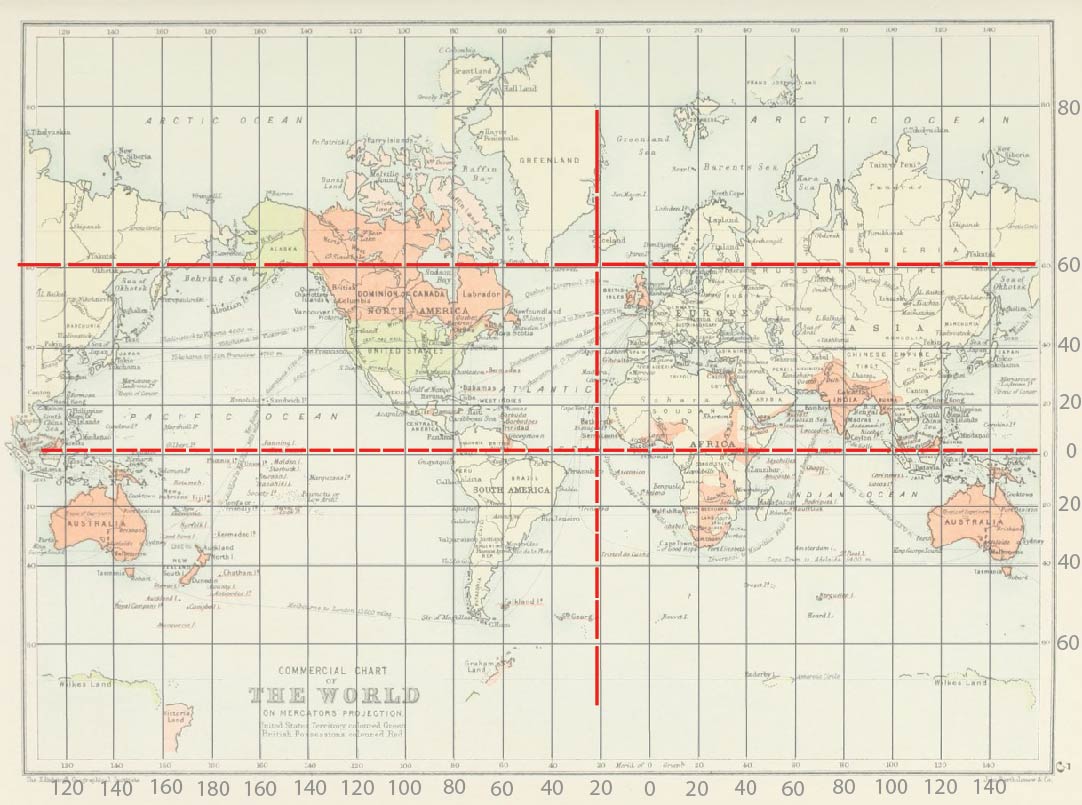

A common map in old school atlases is a one of the world given in the Mercator projection, such as this one:

From J. G. Bartholomew, Graphical Atlas and

Gazetteer of the World, New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1892, p.3.

Larger

To begin with, a map like this contains extensive topological information about the relations among the various parts in the space. We see that Canada and the US touch, but that the North American continent is separated from Europe by an ocean. If we could look in more closely, we would see that Austria is fully land-locked within Europe, being surrounded by other countries on all its borders.

More precisely, the topological properties of a space are just those that are unaffected by continuous deformation of the space. Figuratively that corresponds to stretching and shrinking the space like a rubber sheet, but without cutting, tearing or rejoining parts. (Hence topology is sometimes called "rubber sheet geometry.")

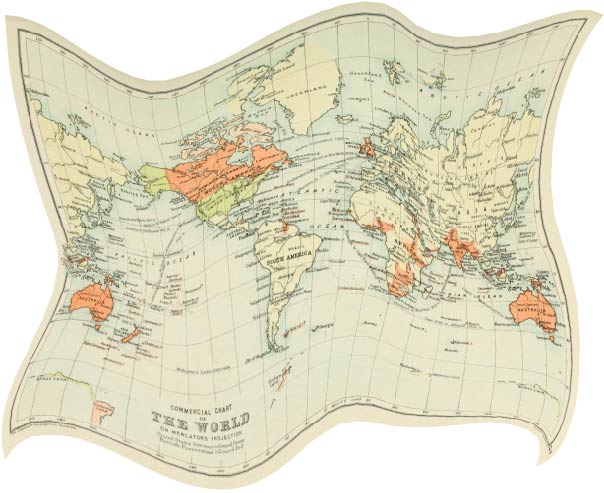

Here's the same map after it has undergone such a deformation. This deformed map and the original map contain the same topological information. Canada and the US still touch. North America is still separated from Europe by an ocean. And so on.

What is missing from the topological information is anything about distances. We have all the countries in both maps. But they have different sizes. Information about their sizes--how much distance, say, separates their Easternmost and Westernmost points--changes when we deform the map. That information is not topological.

We need extra information to know how much distance there is been two points in the map. That extra information is "metrical." More precisely, the metrical structure specifies the distances along any curve we may draw in the space.

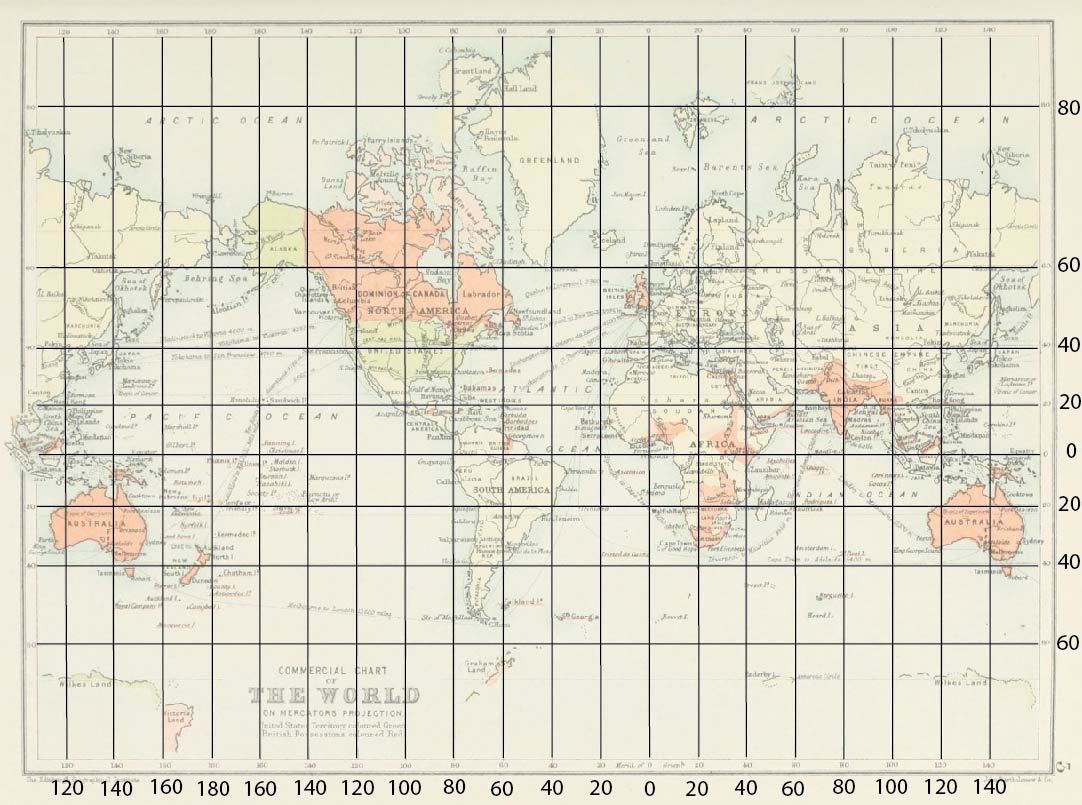

The metrical structure of the map is supplied by the grid of lines of longitude and latitude. They are emphasized below:

This grid of line supplied the metrical or distance

information only indirectly. But it is there as long as one knows how to

read it. To start, consider the equator. We track positions along the

equator with the lines of longitude. A nautical mile is defined so that

one degree of longitude at the equator corresponds to 60 nautical miles.

Hence we have:

ten degrees of longitude at the equation = 600

nautical miles

We will now use this 600 miles as the unit of a measuring rod--red sticks

in the figures below--that we will transport over the surface of the

earth.

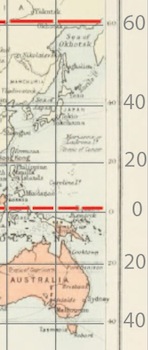

| The detail of the map at the right shows the rods

laid out along the equator. The meridians (vertical grid lines) are

separated by 20 degrees of longitude, so, at the equator, we fit two

rods between the successive meridians shown. As we move North from the equator, however, the meridians approach. They will eventually meet at the North Pole. Once we have moved northward beyond Japan to 60 degrees of latitude, the distance between the adjacent meridians is halved. So now we can only fit one of our 600 nautical mile measuring rods into the space between the meridians. Why is it halved at 60 degrees of latitude? The general formula is that the distance between the meridians shrinks with the cosine of the latitude; and cos (60) = 1/2. However the distance between the meridians on the paper of the map remains the same. Hence the map stretches true distance in the East-West direction as we move North and South from the equator. |

|

What about distances in the North-South direction? An important, even defining, characteristic of the Mercator projection is that the amount it stretches distances is the same in both directions: North-South and East-West. That tells us that we can use the same rods, rotated from the East-West orientation to the North-South orientation, at each point of the map. Here is a map with more 600 nautical mile measuring rods spread over its surface.

Here's some map trivia.

| This last fact, that the projection stretches

equally in both directions, is an artifact of the original purpose

of the projection. The Mercator projection was designed to be useful

to sailors. It has the important property that the path of boat

sailing on a constant bearing comes out as a

straight line. The map detail shows a course that is

everywhere North-Easterly. If that is to come out as a straight

line, the distance on the map sailed in the Easterly direction must

correspond to the distance on the map sailed in the Northerly

direction. That requirement just amounts to the map stretching

distance equally in both directions. This is a great convenience to navigators at sea plotting their courses on their nautical charts. It is great annoyance to geographers who lament that the Mercator projection grossly exaggerates the size of countries in far Northern and Southern latitudes. |

|

The Mercator projection captures the components of the geometry at issue here. The topological structure of the space comprises all those properties that are unaffected if the map were printed on a rubber sheet and continuously deformed. The metrical structure is the full catalog of distances along curves in the map. That information is supplied by the grid of lines of longitude and latitude, once one knows how to read it.

The thesis of the conventionality of geometry asserts that the metrical structure of a space may be chosen conventionally.

One of the earliest to advocate this view was Henri Poincaré and he did it at a time prior to general relativity. He argued in his Science and Hypothesis (1905, p. 58) that geometry is really a reflection of the physical properties of the bodies we use as measuring rods, when we survey a space. He concluded (his emphasis):

"The geometrical axioms are therefore neither synthetic a priori intuitions nor experimental facts. They are conventions."

| He introduced what has become an iconic

representation of his claim. He asked us to imagine a disk with a

strong temperature gradient over its surface. It is hottest at the

middle and cools off to absolute zero at the circumference. We have

measuring rods that can be placed over the surface. They instantly adopt

the temperature of the part of the disk on which they are

placed. They contract in direct proportion to the temperature. The figure below shows a diameter AA' of the disk. Unit measuring rods are laid along it and they shrink as the rods near the coldest edge. If a rod were to be placed at the edge of the disk, it would shrink to no size, for the temperature there is absolute zero. However the successive placement of the rods will never allow this. Since they shrink towards zero size the closer we come to the circumference, it turns out that infinitely many unit rods will fit along the diameter. That is, as far as the geometry revealed by the rods is concerned, the diameter is infinitely long. That is, the space is infinite! |

Poincaré actually asked us to imagine a sphere and

he carried out the constructions within it. The extra dimension does

not affect the analysis. The construction was not novel to Poincaré. It had been used to display the relative consistency of different geometries in the 19th century. Poincaré now put it to a new use. The specific rule Poincaré used is that the temperature is proportional to (1 - (radial coordinate)2). This returns a homogeneous, hyperbolic geometry. |

The diameter AA' turns out to be a geodesic of the measured geometry of the surface. That is, it is a line of shortest length. What about other geodesics? They manifest as arc of circles in the geometry of the paper or screen of this page. For example, the line BB' is a straight line of the geometry, that is, it is a geodesic of shortest length. By diverting inwards toward the hot center, the line needs fewer rods to traverse the disk. It is also infinitely long, as is AA'

Finally, the geometry turns out to be the familiar hyperbolic geometry of 5MORE That we have discussed in an earlier chapter. We can see how the alternative to Euclid's fifth postulate, 5MORE, is implemented in the geometry in the above figure. Consider the point P not on the straight line AA'. Line DD' through P is also a straight line of infinite length that does not intersection AA'; that is, DD' is parallel to AA'. There are many more such lines. CC' and EE' through P are also infinitely long straight lines that do not intersect AA' and are thus also parallel to it.

Poincaré's point is this. Here we have a disk and we measure its geometry with measuring rods. One sort of rod that does not respond to temperature will tell us the metrical geometry is Euclidean. Another sort of rod that does respond to the temperature will tell us it is hyperbolic. There is no independent fact of the metrical geometry of the surface. Which metrical geometry we recover depends on our choice of which measuring rods we choose to use. That is, we choose the geometry.

Poincaré's ingenious analysis of metrical geometry may well have faded from view, were it not for a strong, later endorsement by Einstein. In 1921, Einstein gave a lecture, "Geometry and Experience," before the Prussian Academy of Science. In it he gave his version of Poincaré's argument:

"Why is the equivalence of the practically-rigid body and the body of geometry—which suggests itself so readily—rejected by Poincaré and other investigators? Simply because under closer inspection the real solid bodies in nature are not rigid, because their geometrical behavior, that is, their possibilities of relative disposition, depend upon temperature, external forces, etc. Thus the original, immediate relation between geometry and physical reality appears destroyed, and we feel impelled toward the following more general view, which characterizes Poincaré's standpoint. Geometry (G) predicates nothing about the behavior of real things, but only geometry together with the totality (P) of physical laws can do so. Using symbols, we may say that only the sum of (G) + (P) is subject to experimental verification. Thus (G) may be chosen arbitrarily, and also parts of (P); all these laws are conventions. All that is necessary to avoid contradictions is to choose the remainder of (P) so that (G) and the whole of (P) are together in accord with experience. Envisaged in this way, axiomatic geometry and the part of natural law, which has been given a conventional status, appear as epistemologically equivalent."

(G) + (P)

This was a powerful endorsement of the conventionality thesis from Einstein just as he was rising to celebrity status, after the success of the 1919 eclipse expeditions that tested his general theory of relativity. Earlier in the lecture, Einstein had stressed the importance of the starting point: that geometry is an empirical science whose laws are to be discovered from measurements. That view, he asserted, was important in his original discovery of general relativity. He explained:

"I attach special importance to the view of geometry, which I have just set forth, because without it I should have been unable to formulate the theory of relativity. Without it the following reflection would have been impossible: in a system of reference rotating relatively to an inertial system, the laws of disposition of rigid bodies do not correspond to the rules of Euclidean geometry on account of the Lorentz contraction; thus if we admit non-inertial systems on an equal footing, we must abandon Euclidean geometry. Without the above interpretation the decisive step in the transition to generally covariant equations would certainly not have been taken."

Here Einstein is recalling his analysis of rotating disk from his work of 1912. (We discussed it here.) Einstein's rotating disk and Poincaré's disk are not the same, but they are obviously close in their approaches.

The notion of a conventionality of geometry was soon picked up by Einstein's foremost expositor and philosophical commentator, Hans Reichenbach. His 1927 Philosophy of Space and Time gave the conventionality of geometry pride of place in the opening Chapter 1 on space.

His version of the Poincaré disk involved a flat glass surface "G" with a hemispherical hump in the center. Reichenbach's figure is redrawn below:

| Humans on the glass surface G would explore its surface with measuring rods and soon find that their surface has a hump in it. Reichenbach now imagined a light high above that cast shadows of the rods of G onto a second flat surface E. These shadow rods would return a non-Euclidean spherical geometry in the vicinity of the hump. While all the rods of the surface G would be the same length, their shadows on E would not. So the distance A'B' would equal that of B'C' on the glass hump. But the shadow AB would not be the same length as BC on the surface E. That is, they would differ according to the Euclidean geometry native to E. |  Hans Reichenbach |

But now imagine, Reichenbach continues, that the measuring rods available to the E-people are forced to conform to the lengths of the shadows, then those rods would return a spherical geometry. What might force them to behave so? One might have temperature differences that enforce the requisite expansions and contractions.

Reichenbach's analysis matches that of Poincaré in general outline. One major difference is that Poincaré considered only geometries of constant curvature. Reichenbach uses a surface which has zero curvature in one place and positive curvature in another. This is an extension that, we might guess, would be unwelcome to Poincaré.

|

Reichenbach did address the obvious weak point in the Poincaré analysis. The use of a temperature based disturbance asks a lot of the reader. We must ignore that the large changes in temperature Poincaré imaged are something we can detect independently of the contraction of rods. As we move closer to absolute zero, different substances liquefy and freeze at different temperatures, which would immediately reveal temperature based disturbances. Even if we ignore those effects, we have the problem that different materials contract and expand differently for the same temperature differences. (Hence a Mercury in glass thermometer can only work because Mercury expands more on heating than does glass.) That would mean that measuring rods made of different substances would return different geometries. |

Reichenbach made this problem a focus of extended discussion. He distinguished all those forces that act differently on different substances as "differential forces." Those would not be the basis of his analysis. Instead, he would consider "universal forces." They are, by supposition, free of these effects. They act in the same way on all materials; and there is no way to shield materials from them. To make his and Poincaré's example work, we are to assume that the rods used to explore the space are acted upon by universal forces.

Reichenbach's version of the conventionality thesis could now be stated. The measuring rods we use to explore the geometry of a space are real rods whose lengths have been corrected for all differential forces. If the space is warmer in one area, we know how much that leads our steel rods to expand. We correct for it. However there is no way we can make a corresponding factual correction for universal forces. For there is no way to ascertain by measurement just which are acting. We must stipulate that there are none. This need to stipulate away universal forces makes our choice of idealized measuring rods a matter of definition. It is a "coordinative definition" that coordinates the corrected lengths of real rods with the notion of length in the geometry.

Reichenbach's text became a defining document in philosophy of space and time in the mid and later part of the 20th century and the thesis of the conventionality of geometry figured prominently in it.

That celebration of the thesis, however, overlooked the fact that Einstein's endorsement of it had been equivocal. Immediately after his summary of it in "Geometry and Experience," Einstein moved to what amounted to a retraction:

| "Sub specie aeterni"is literally "from the perspective of eternity." We might now merely say "in the long run." | "Sub specie aeterni Poincaré, in my opinion, is right. The idea of the measuring-rod and the idea of the clock coordinated with it in the theory of relativity do not find their exact correspondence in the real world. It is also clear that the solid body and the clock do not in the conceptual edifice of physics play the part of irreducible elements, but that of composite structures, which must not play any independent part in theoretical physics. But it is my conviction that in the present stage of development of theoretical physics these concepts must still be employed as independent concepts; for we are still far from possessing such certain knowledge of the theoretical principles of atomic structure as to be able to construct solid bodies and clocks theoretically from elementary concepts." |

Einstein makes clear here that his endorsement of the conventionality thesis depends upon a particular view of measuring rods (and clocks). They are not to be considered as something outside the scope of the physics under discussion. Their constitution and behavior are to be part of the physics investigated. He is imagining here how he expects physics to be if he could complete his program of the unified field theory. Under that program, all of the geometry of space and time, gravity and all matter fields would be combined into a single unified field. With that goal achieved, Einstein expected, there would be considerable latitude in our division of this field into geometrical and matter parts. As a consequence we could choose a different geometry by making the division in different ways.

What Einstein makes clear is that this time has not yet come. We did not know at the time of his writing (or even now) how to merge everything into one unified field. So we must proceed as we did before. We must take the rods and clocks as idealized elements supplied independently of the physics at issue. Then there is no convention. We must settle for whichever geometry the measurements deliver.

For another, lengthier statement by Einstein of his view on the conventionality of geometry, stated in a 1924 book review, see this.

The thesis of the conventionality of metrical geometry achieved widespread attention because of its connection to Einstein, Reichenbach and, indirectly, general relativity. However, in the form of the thesis given by Poincaré and Reichenbach, there is no logical connection to general relativity. Their arguments for the thesis could have been made at any time since Euclid. They were not since, I believe, in the larger perspective, they are unappealing.

I find it hard to see that an interesting sense of convention in geometry has been identified. Absent the complete reconfiguration of physics imagined by Einstein with his unified field theory, the situation with geometry is just one of fairly straightforward discovery. We have many instruments for measuring length, some less reliable, some more so. We routinely correct the measurement for known deficiencies in the instruments. No careful measurement of a long distance with a metal tape can be precise if we do not correct for the small sag in the tape. When we perform these measurements of space by these different instruments, we recover a single metrical geometry of space. The instruments agree on it. That is our geometry.

The arguments above for conventionality of geometry depend on the notion of a universal force, or something like it. They are forces that, supposedly, act on all of us. Yet there is no way to establish independently what their magnitudes are or even that they are present at all. They are entities protected from evidential scrutiny by careful contrivance. In our earlier treatment of verificationism, I concluded that we should regard such constructs with great suspicion. That applies to universal forces.

If we persist in allowing universal forces in our analysis, then we eliminate any interesting distinction between the conventional and the factual. For analogs of universal forces can be invoked to render any measured quantity conventional. All we need is that the quantity is measured by some instrument or instruments. We posit a universal disturbing force that acts equally on all instruments that measure the magnitude. Hence, there is no empirical way to detect the universal disturbing force. Following Reichenbach, it is a matter of convention that we set the force to zero. That, supposedly, means that we are setting the magnitude by convention. If we accept the arguments that favor the conventionality of geometry, we must also conclude that every measured magnitude is chosen conventionally.

The general theory of relativity has geometrized gravity.

The thesis is stated tersely since any attempt to expand it leads us directly to the principal difficulty with the claim. It has so many meanings that one despairs of finding a single claim that is really intended across the literature. This is a case in which our main task is merely to discern what the thesis claims. Once we have more precise formulations of the many readings, we need worry less about the arguments that support them. Some are so obviously false that they are dismissed automatically. Others are so clearly asserting truths that we need not labor over them, although we will feel that the truths asserted are much less exciting than the grand image conjured by "geometrization."

Let me lay out some readings.

This is the most natural reading that comes to beginners who are struggling to learn general relativity. It is not what is intended by the experts who write the popular texts that speak with enthusiasm of how general relativity had geometrized gravity. However it is how they are understood by their eager and forgiving readers, struggling to grasp an abstruse theory.

The conception is simple. There are numerous cases in science of successful reductions. We once thought that living matter differed in some principled way from dead matter. It was animated by some sort of living spirit without which no mere laboratory experiment could convert dead matter into living matter. Doctor Frankenstein could not reanimate his monster without re-energizing it with the spark of life. Then we learned that all life is just chemical; there is nothing in a living being beyond the chemistry of constituents.

A second example, closer to physics, is light. At the start of the 19th century, light, electricity and magnetism all appeared to be independent things. You could have any one without the others. By mid century, Maxwell was able to show that light really was nothing more than the propagation of a wave-like disturbance in the electromagnetic field. Light was reduced to electromagnetism.

In both cases, the key result is that the chemical properties of a living being are really all there is to its life properties; and the electromagnetic processes in space are all there is to any light present.

The beginner's entirely predictable reading is that general relativity has done the same to gravity. We had thought that gravity was something independent of geometry in this sense. We now learn that gravity really reduces to the geometry of space. The geometry of space is really all there is to any gravity present.

Here the essential point is that geometry is understood in its common meaning: it is the study of the metrical properties of ordinary space. It deals with the distance between points in space, the areas encompassed by lines, and so on. That the geometric facts can also exhaust all gravitational facts is implausible to the beginner and definitely mysterious. Somehow, the beginner is assured, it all works out once we attend to the possibility of a non-Euclidean geometry.

Experts in relativity theory may find it hard to see that

this misreading is fostered. They are forgetting the single most

misleading image of popular accounts of the theory. It is image

of a rubber sheet deformed by mass of a planet. The deformed sheet

embodies the non-Euclidean geometry. Somehow a ball rolling around on the

sheet illustrates the presence of gravity.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Spacetime_curvature.png

Beginners are wondering--entirely correctly--if gravity has been

geometrized away, what force is pulling the planet down so that it deforms

the sheet. The sad truth is that the figure is an irretrievably muddled

confusion of ideas.

For a reminder of the part of the physics that this diagram does get

right, see The

Geometry of Space in the chapter Gravity

Near a Massive Body.

This is the best reading I can find for the thesis of geometrization of gravity.

Prior to general relativity, gravity was conceived as a force deflecting masses away from their natural inertial motion. One would expect that the the greater the mass of the body, the stronger the pull of gravity on it and so the greater the deflection. The curious result was that the greater mass of the body was precisely compensated in Newtonian theory by a correspondingly greater inertia. Hence all bodies in free fall, heavy or light, traced out the same trajectories.

Einstein explained this otherwise curious coincidence. He relocated the trajectories of free fall into the background spacetime structure. Bodies light and heavy followed those trajectories independently of their masses, just as trains, large and small, follow the same track over the mountain.

A Minkowski spacetime was already equipped with preferred trajectories. They are the timelike geodesics that coincide with inertial motions. What Einstein recognized was that free fall trajectories under gravity could be incorporated into this background structure by the simple expedient of introducing curvature into the background. (For more, see Uniqueness of Free Fall in the chapter General Relativity.)

So far, we have a clear and fair accounting of how general relativity altered our theoretical representation of gravity. The difficult question is this: Why should we describe it as geometrization? Recall that the meaning of the term "geometry," at least for our first few millennia, is study of lengths and related metrical properties of of ordinary space. We are now dealing with a spacetime. Why is geometry the right word?

We can see some rationale for it, if we take one step back and recall Minkowski's contribution to special relativity. He found a spacetime formulation of the theory that had striking analogies to the ordinary geometry of space. We saw in an earlier chapter (Spacetime: Minkowski Spacetime Geometry) that they both dealt with a notion of distances in a space. For geometry it was ordinary length. For special relativity it was the interval, which combined measured lengths and times. The analogy was quite close in some aspects. The circles of Euclid are the analogs of the hyperbolas of Minkowski.

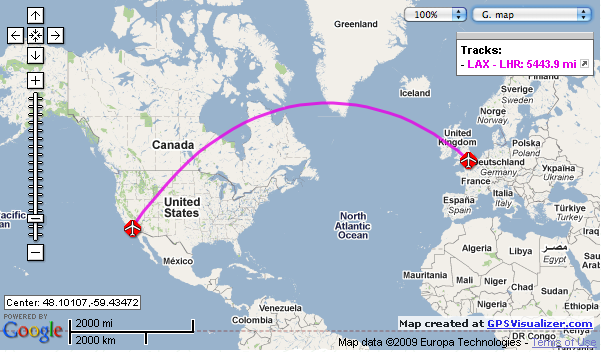

| We explain why the airline path from the US to Europe looks curious on an ordinary map. It is a geodesic of the curved geometry of space that is poorly adapted to the Euclidean surface of the map. | Correspondingly we explain why a planet in free fall orbits the sun: the orbital trajectory is a geodesic of the spacetime. |

|

The disanalogies remain and are important. Space is the same in all directions, whereas spacetime distinguishes the spatial from the temporal direction. Spacetime must respect the distinction between spatial and temporal. Changes in time are quite distinct from differences of position, even if they all are collected in the one spacetime picture.

This is as close as I can bring the general relativistic account to the spatial geometric account. The two are clearly analogous. But to say that explanations in general relativity are analogous to explanations given in spatial geometry is not the same as saying they are explanations in spatial geometry.

If matters could be left in this state, they would be difficult enough. The complication is that there has a been a slow migration and broadening of the terms "geometric," "geometrize," and so on in the modern literature. Now they have meanings that are so broad that it is hard to know precisely which sense is intended when they are invoked.

One broadening retains the idea that the trajectories of free fall are relocated in the background spacetime structure. However it does it in a way that breaks the analogy between Euclidean geometry and Minkowski spacetime described above. The essential similarity is that both are metrical geometries; that is, they are both concerned essentially with a notion of distance. There are spacetime versions of Newtonian theory that relocate the free fall trajectories into the background spacetime structure in a quite different way. The so-called "affine structure" in a spacetime merely picks out which are the lines designated as straight, without supplying a fully developed notion of times elapsed and distances passed. "Geometrized Newtonian Theory" relocates the free fall trajectories into this structure by curving it. There are other cases of this broadening. One arises in gauge field theories in quantum theory (which I will not try to explain here).

This is a third way that the term "geometry" is used. It no longer designates physical ideas. Rather it denotes a decision by a theorist to use a particular mathematical formalism. This quite distinct sense of geometrical is commonly tangled up in claims that general relativity has geometrized gravity, for general relativity was the first physical theory to be developed fully in the geometric-as-coordinate-independent manner. The muddling of the two senses is, I suspect, a problem that besets even the experts.

Here's how the notion looks in the simple case of picking out the inertial trajectories in a Minkowski spacetime.

| Coordinate dependent approach. We label events in spacetime with four coordinates: three numbers (x,y,z) for spatial position and one number t for temporal position. To have things work out well, we choose the four coordinates carefully, so that differences of the spatial coordinates correspond to measured spatial lengths in an inertial frame; and differences of the time coordinate correspond to differences of proper time for clocks of the frame. An inertial trajectory is a timelike curve along the spatial coordinates, x, y, z, are each proportional to the time coordinate t. This condition is coordinate dependent in the sense that we have to pick the right coordinate system in which to implement it. Use another coordinate system that does not have the close connection between the coordinates and measured spaces and times and the condition fails. |

Coordinate independent approach. We saw earlier that we can pick out the inertial trajectories in a Minkowski spacetime by what we would now call a "geometric" rule: The inertial trajectories are those timelike curves along which the maximum proper time elapses. This condition is coordinate independent in the sense that it does not matter which coordinate system we may happen to work in. The proper time elapsed along a timelike curve is the same in all of them. |

| |

|

Generally speaking, more mathematically oriented physicists have come to prefer formalisms that work equally well, no matter which coordinate system is employed, no matter how messy the coordinate system might be. Their fear is that sometimes an odd selection of coordinates can deliver effects that look physical but are merely an artifact of badly chosen coordinates. The structures that work equally well in all coordinate systems are called "geometric objects." A physical law expressed in terms of geometric objects will be written the same in all coordinate systems.

A geometrical treatment of some piece of physical theory is simply one that employs these sophisticated mathematical methods. Since they are merely a mode of description, employing them makes no difference to the physical content of the theory. The use of geometrical methods, in this sense, is merely a warning to the reader that certain advanced techniques will be used. Announcing a geometrization of gravity in this sense makes no physical assertion at all.

| Translations of Einstein quotes in this section are drawn from Dennis Lehmkuhl, "Why Einstein never really cared for geometrization" (Reference link coming soon; in the meantime, contact Dennis.) This work should be consulted for a full account of Einstein's perspective on geometrization in general relativity. | One might imagine that Einstein was in the forefront of those urging that general relativity has geometrized gravity. This is not the case at all. Einstein was solidly opposed to the claim and publicly argued against it. |

Einstein's clearest statement come in his review of Émile Meyerson 1925 La Déduction Relativiste. In a commentary published in 1928, he first characterized one of Meyerson's theses as a reduction claim:

"Meyerson sees another essential correspondence between Descartes’ theory of physical events and the theory of relativity, namely the reduction of all concepts of the theory to spatial, or rather geometrical, concepts..."

Einstein is sharp and unequivocal in his repudiation:

"...I have an entirely different opinion on the matter. I cannot, namely, admit that the assertion that the theory of relativity traces physics back to geometry has a clear meaning...."

He explains a little later, mentioning the "metric tensor," which is the mathematical quantity that assigns spacetime intervals to displacements along curves in a spacetime:

"...The fact that the metric tensor is denoted as “geometrical” is simply connected to the fact that this formal structure first appeared in the area of study denoted as “geometry”. However, this is by no means a justification for denoting as “geometry” every area of study in which this formal structure plays a role, not even if for the sake of illustration one makes use of notions which one knows from geometry. Using a similar reasoning Maxwell and Hertz could have denoted the electromagnetic equations of the vacuum as “geometrical” because the geometrical concept of a vector occurs in these equations."

In effect Einstein is repudiating the strength of the analogy sketched above between Euclidean geometry and the spacetime structure of general relativity. That we first learned of structures like those used in general relativity from ordinary geometry does not license us to call them all geometrical.

My view is easy to state: I think Einstein is right. And he is right for the reasons he gave.

To review the three senses of "geometrize" given above, (a) proves to be factually incorrect and not really intended by any relativists. It survives mostly as an artifact of oversimplified and hence failed popularizations. (c) is physically empty and thus tells us nothing about the world. Something like (b) is correct and important, but geometrization is a poor description of its content.

Copyright John D. Norton.

February 23, 2013. Some material removed and developed into new

chapters, November, 2019.February 6, 2022.